F.W. Stevens with Sitaram Khanderao and Madherao Janardhan, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus), begun 1878, Mumbai, India (photo: Ajit A. Kenjale, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Palatial architecture meant for daily use

Countless passengers and goods have travelled from the railway platforms of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (Mumbai, India), since it was constructed for the British colonial government in 1878. With its gargoyles, griffins, domes, and towers, the Terminus recalls all at once a palace (in its scale), a political capitol (in its great central dome), a grand hotel (in its accommodation of travelers), and a cathedral (in its gothic tracery). In its political impetus and its grandeur, the Terminus was designed to express British colonial authority in India. Railways were one of the economic engines of the 19th century, and an essential tool for colonial administration and authority.

St. Pancras Station (Midland Grand Hotel), London, 1873

(photo: David Skinner, CC BY 2.0)

London in Bombay

Victoria Terminus echoes the Saint Pancras Railway Station in London, a polychrome Gothic Revival confection that had been finished some years earlier.

Like Saint Pancras, the Terminus in Mumbai is encrusted with decorative architectural references drawn from centuries of European history. A short list includes delicate Gothic quatrefoils, ancient Roman-style roundels with bust portraits, and thick Romanesque piers.

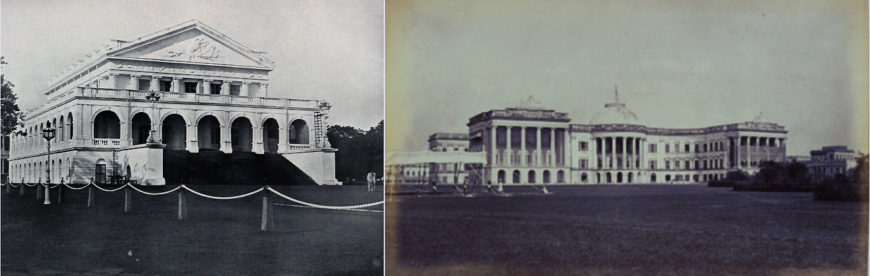

Neoclassical colonial architecture in India; left: Banqueting Hall (now Rajaji Hall), 1802, Chennai (photographed c. 1905); right: Government House (now Raj Bhavan), 1803, Kolkata (photographed c. 1865)

This was a change, since many earlier colonial administrative buildings dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries had emulated the Neoclassical style; examples include the Banquet hall in present-day Chennai built in 1802 and the Government House built in 1803 in present-day Kolkata.

The Terminus was originally named for Queen Victoria, the 19th century British monarch, who counted India among her colonies. In 1996 the Terminus was renamed in honor of Chhatrapati Shivaji, the royal title of a seventeenth-century Indian ruler named Shivaji who’s legacy later became associated with India’s independence movement from British colonial rule.

F.W. Stevens with Sitaram Khanderao and Madherao Janardhan, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus), begun 1878, Mumbai, India, taken c. 1870 (public domain)

Building empire

Construction on the Terminus began in 1878 and took a decade to complete. It replaced a modest existing railway station and served as the headquarters of the Great Indian Peninsular Railroad. The development of railways in India was well underway when Mumbai’s importance as a trading port significantly increased due to the opening of the Suez Canal (a waterway that connects the Mediterranean to the Red Sea) in 1869 which allowed quicker seafaring to England. The Terminus connected Mumbai (known then as Bombay) to a growing network of railways across the country and allowed for the transport of goods meant for export to the docks of Bombay harbor.

Until 1858, British commercial operations in the Indian Ocean had been administered by the East India Company, a trading firm that had established small merchant posts (known as factories) in India as early as 1611. Although the Company’s competitors—the Dutch and Portuguese trading companies—were already in India by that time, the British East India Company would become a dominant force in Indian Ocean trade.

As the once powerful Mughal empire began to wane, British influence grew. The Company increased its territorial holdings through military operations, by installing puppet monarchs and by annexing princely states. An uprising against the East India Company’s oppressive rule led to the First Indian War of Independence in 1857—an event which the British referred to as a mutiny. British forces prevailed in the bloody conflict and exiled the last Mughal ruler from India. In 1858 the administration of the colony came under the direct control of the British Crown.

“(India) . . . ought to be ruled from a palace, not from a country house; with the ideas of a prince, not those of a retail-dealer in muslins and indigo.” Lord Wellesley, c. 1803 [1]

Imperial anxiety and the Indo-Sarascenic

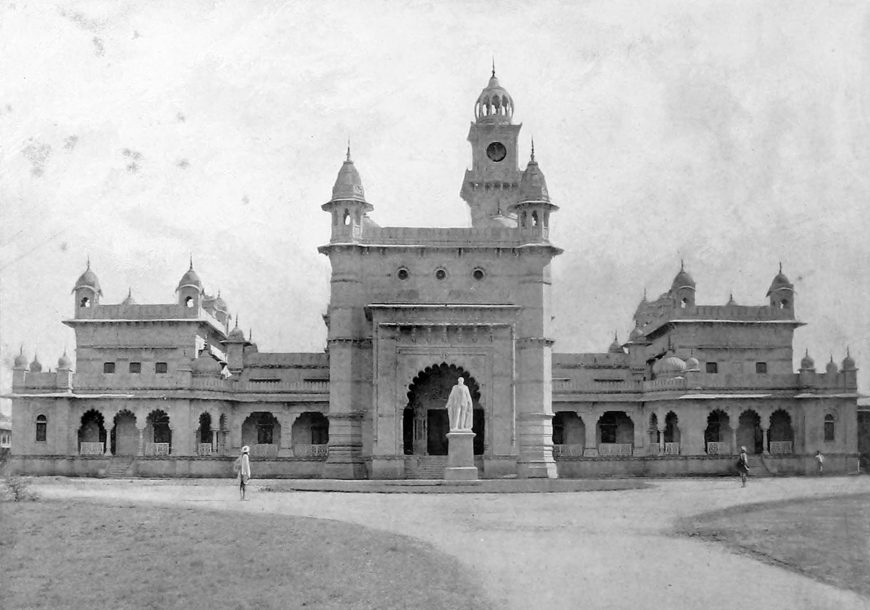

The British Raj (a term for British rule) was eager to be perceived as the legitimate rulers of India and they chose an architectural language for Victoria Terminus and many other buildings that embodied this agenda. The resulting architectural style—known as Indo-Sarascenic—merged the greatest architectural achievements of western history (as the British saw it) with those aspects of Indian architectural history that they deemed admirable.

Mayo College, Ajmer, 1875 (photographed c. 1895, public domain)

The Indo-Sarascenic style clad a western architectural plan with decorative Indic features. The Indic references were predominantly borrowed from the early Buddhist, Sultanate, and Mughal periods. These aesthetic choices were informed by orientalist nineteenth-century British writers, such as James Fergusson who believed that Indian art and architecture had reached its peak with early Buddhist art, and that everything afterward was expressive of a civilization in decline. His exceptions included aspects of Indian palace architecture and Islamic architecture; he especially admired the domes of the latter. While the Indo-Sarascenic style was widely adopted by British architects in India and was used for everything from civic buildings to educational institutions, Bombay was destined to wed two styles, the Indo-Sarascenic and the Gothic.

University of Mumbai, begun 1868 with buildings influenced by Gothic architecture in Italy (photo: Stefan, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bombay Gothic

The Portuguese had gifted seven islands in the Bombay archipelago to Britain in 1662, on the occasion of the marriage of the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza and the English king Charles II. By the mid-nineteenth century, extensive land reclamation had turned these islands into a single landmass. As the strategic importance, economy, and population of Bombay grew, so too did the interest in building in the city’s open spaces. New constructions were supported by both the Bombay Presidency (as the regional colonial administration was known) and private individuals; several Indian philanthropists were involved in the funding of some of the city’s most important buildings.

Gothic Revival—an architectural movement inspired by medieval Gothic architecture and that was popular in England—was preferred over the Neoclassical style in nineteenth-century Bombay in part because, in the wake of the American Revolution (begun 1776) and the French Revolution (begun 1789), Neoclassical architecture had become associated with Enlightenment ideas of self rule. In contrast, the Gothic style was associated with divine authority—ideal symbolism for colonial occupation. Mumbai’s law courts, university buildings, and municipal offices were all inspired by the Gothic Revival style.

The Terminus

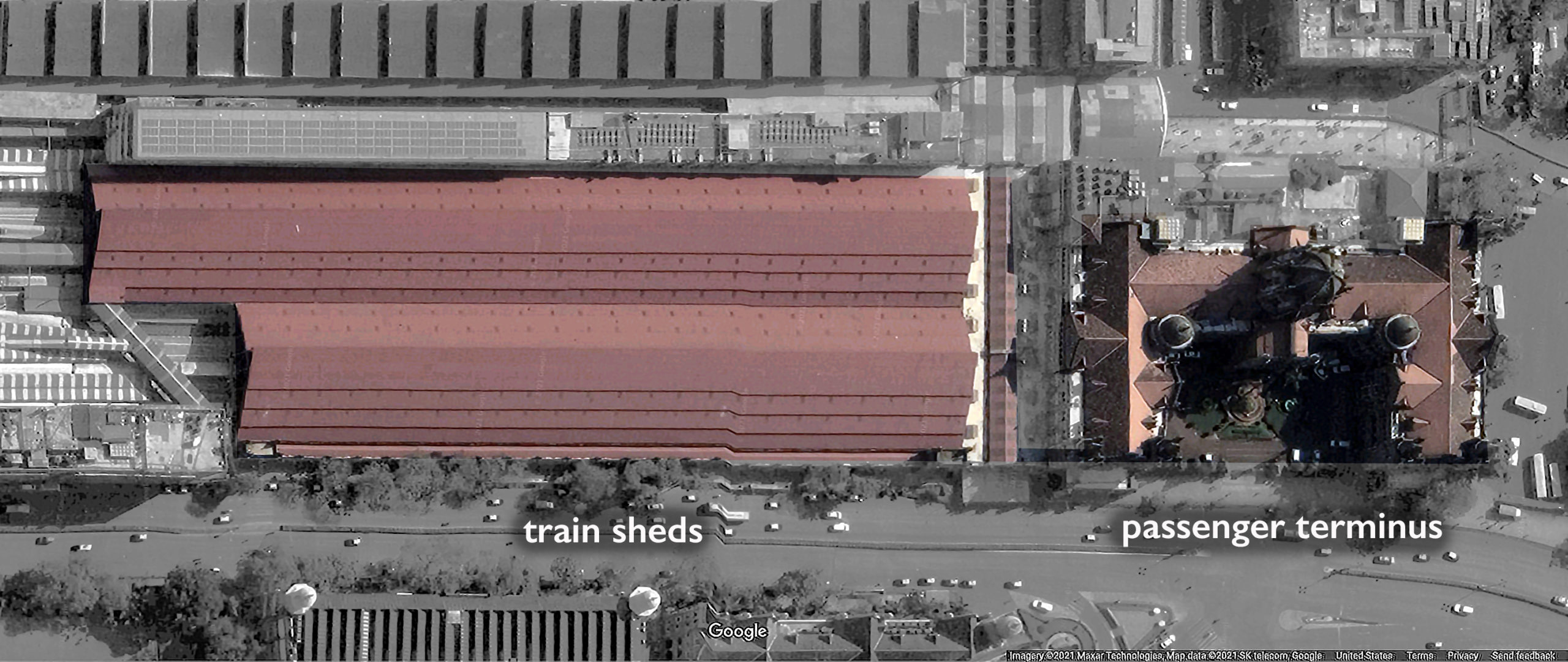

The Terminus, with its Indic and Gothic features, was designed by F.W. Stevens, and the engineers Sitaram Khanderao and Madherao Janardhan. It is considered the foremost example of Gothic Revival in Mumbai. The building is massive and reaches the imposing height of an estimated 330 feet tall. It’s façade forms a U that hugs the entry courtyard. The train shed is not aligned with the passenger terminal, but is placed at the left of the building.

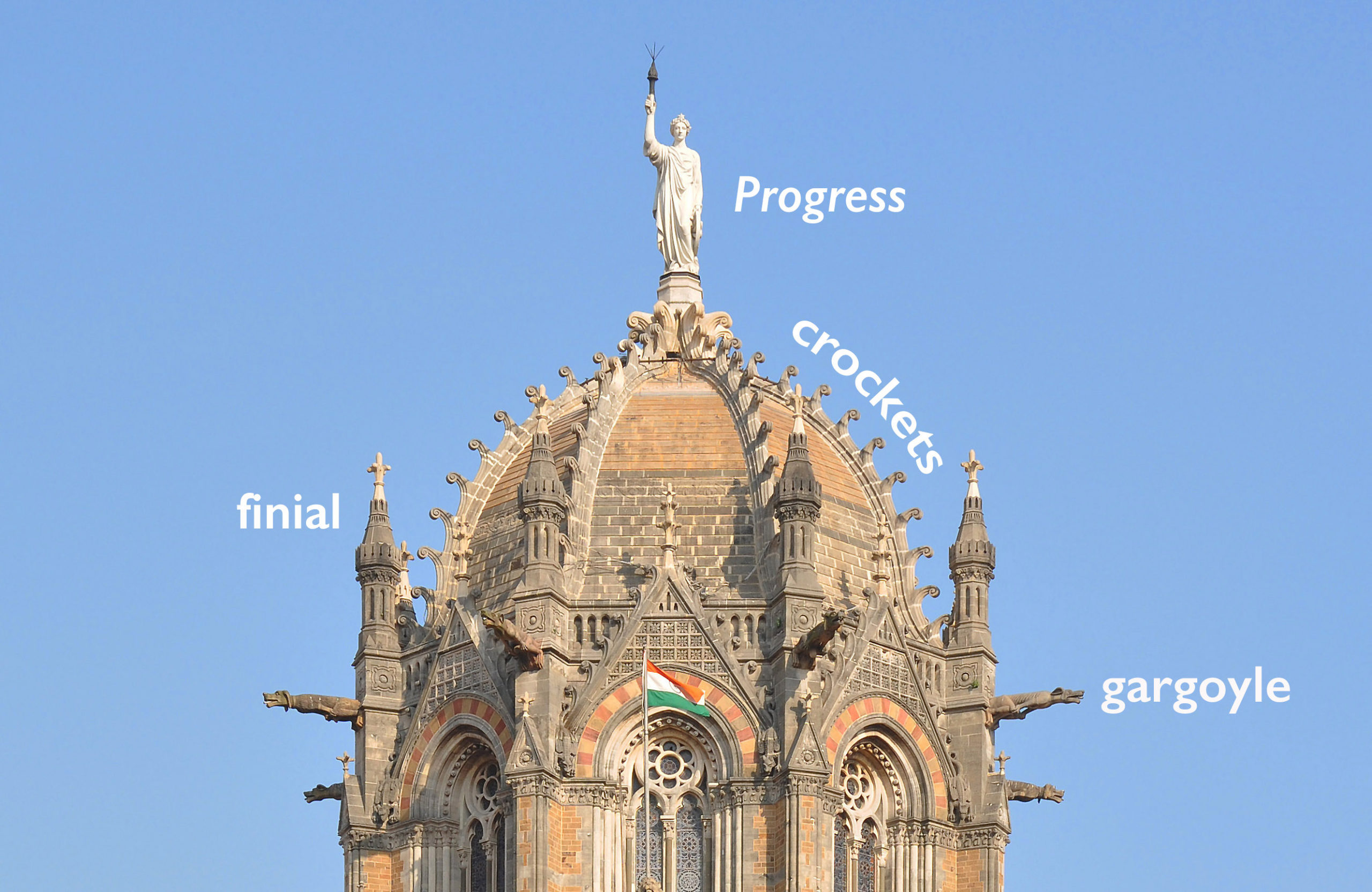

Dome with annotation, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Joe Ravi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Marking the center of the main building, a prominent dome rises ringed with projecting gargoyles, a fanciful detail found on Gothic cathedrals. The dome is ribbed with crockets (curled leaf forms commonly found in English Gothic churches) and it is topped with a fourteen-foot tall allegorical figure of Progress, a central justification used by British for their rule in India.

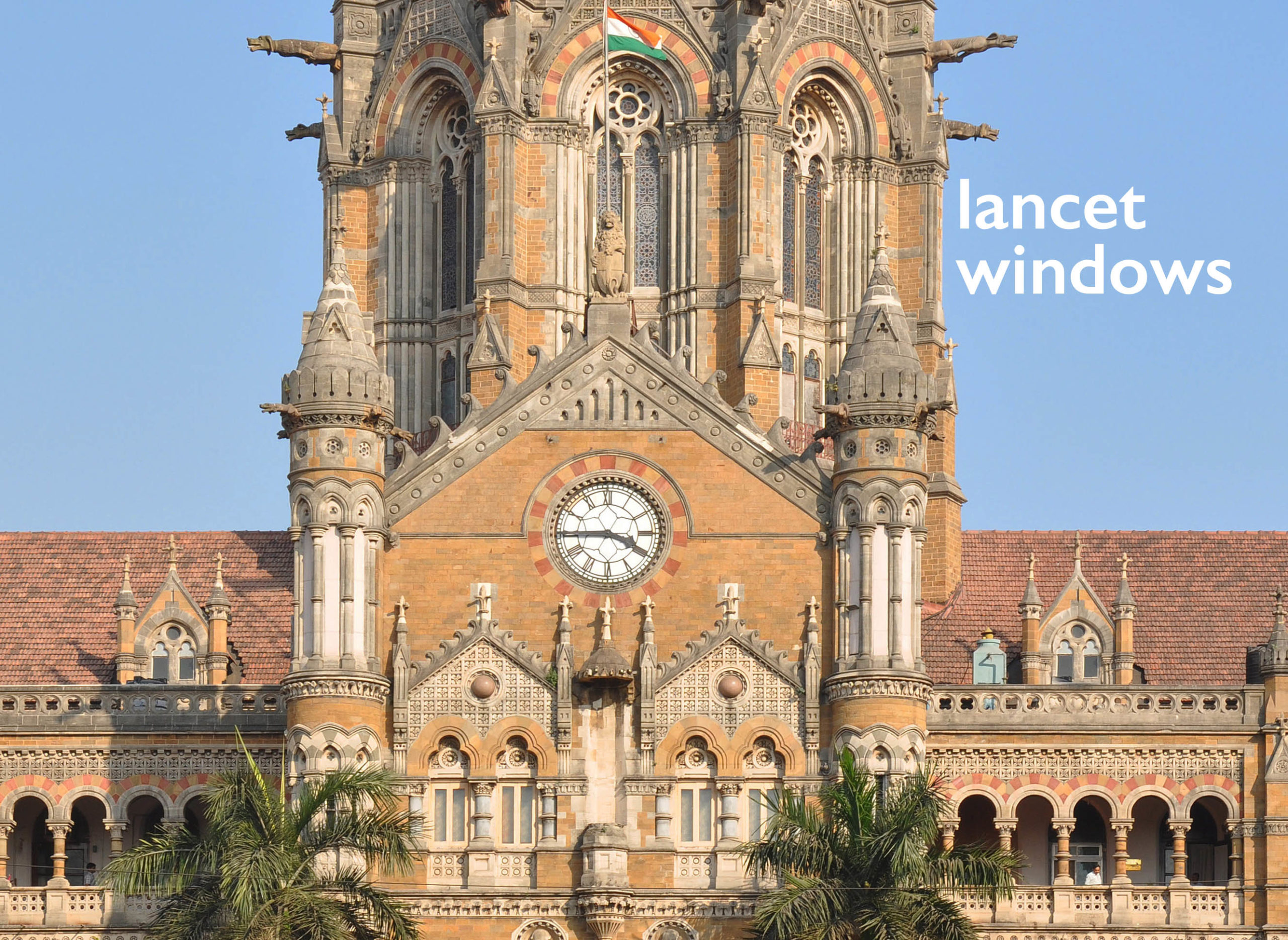

Annotated façade, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Joe Ravi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

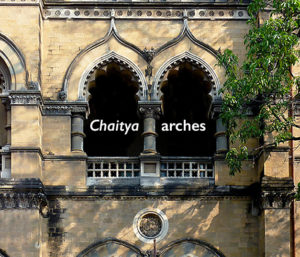

Chaitya arches, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Gioconda Beekman, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Beneath the dome are paired lancet windows below a small rose window, all filled with stained glass as can be seen at the medieval cathedral at Chartres. Below the windows, a pedimented (triangular) façade flanked by turrets (small towers) projects from the central part of the building. At the center of this pediment, an enormous clock outlined with alternating red and yellow sandstone (a motif repeated across the building) takes the place of the rose window that would be here, had this been a medieval church. And like a Gothic cathedral, almost every part of the façade is topped with finials.

But the references are not all European. Across the façade, many of the arches that make up the extensive arcades are cusped, mimicking chaitya arches from India (see example at Bhaja cave here).

Despite this truly riotous program of ornamentation, the alternation between perforation and solid stone walls, between angular and rounded forms, and the use of alternating polychromy, all emphasize the building’s essential order and symmetry.

North corner of façade, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: David Brossard, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Polychrome masonry was preferred for the exterior of the Terminus as the natural colors of the stones used is more permanent than paint, especially given the region’s torrential rains. Various types of stone were used in the construction and decoration of the Terminus, including red and yellow sandstone, limestone, red, blue, and yellow basalts, granite, and marble. This rich palette of colors fit well with theories of the Gothic recently popularized by the influential English critic John Ruskin.

The main gate, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Christopher John SSF, CC BY 2.0)

Two heraldic animals—a lion and a tiger that symbolize Britain and India—respectively flank entrance gates that open onto the garden courtyard just in front of the terminus. Carved animals, including monkeys, rats, owls, rabbits, and cobras, are found in unexpected places such as in walkways, friezes, column capitals, and in tympana above doorways.

Carved animal and foliate decoration, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The wildlife are often shown emerging from flora that scholars have identified as Indian. These sculptures were produced locally by the students of the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art, the oldest art school in Mumbai and the first modern art school in India.

Left: St. Pancras, London (photo: __andrew, CC BY-NC 2.0); right: Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The school championed the amalgamation of select Indian and western traditions. If the carved animals are playful references to the marginalia found in medieval manuscripts or the playful sculptures found on medieval churches, and the foliage that they emerge from is indeed Indian in origin, then the terminus is indeed a deliberate amalgam of Indian and European inspiration. It is worth noting that animals are also present in the stonework at St. Pancras in London.

Once inside, the heavy decorative stonework echos the pre-Gothic, Romanesque style, especially in the door jambs and heavy bundled colonnettes. But here as well, European and Indian motifs meet as can be seen in the use of stacked corbel brackets and cusped arches. The entry space is relatively narrow given the scale of the exterior façade, but it soon opens up high above the visitor’s head.

Under the dome, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Ronakshah1990, CC BY-SA 4.0). Note the squinches in the corners.

The main dome rises above a rectilinear shaft lined with partly suspended stairs that cantilever out from the walls. Above, the dome is structured by ribs that spring from corbels and meet at its center. Light enters through tall lancet windows filled with stained glass and gives this space a sense of airiness that is somewhat deceiving, as the dome sits on an octagonal drum atop ornamented squinches. These squinches play an important role. They are located at the corners of the four-walled shaft and transition to the eight-sided dome directly above. This solution can be seen in Sultanate architecture, such as the dome of the 14th-century Alai Darwaza, at the Qutb archaeological complex.

Vaults, columns, pointed arches, and gallery over the aisle, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Linda De Volder, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

The main hall has tall granite piers with attached columns of varying heights and slender colonnettes. Each column is topped with foliate capitals that were carved in-situ. [3] The hall’s eight-part ribbed vaults (made of wood) were originally painted blue with golden stars to mimic a starry sky—a tradition found in many Gothic churches. All this forms what is essentially a two-aisled nave that is flanked by side aisles defined by a nave arcade made of pointed arches (the ticketing office fills one of the side aisles, while the other opens onto the train platforms). Above are galleries, as you might expect to see in a Gothic Cathedral.

The original rich coloring of the stone and tile-work has faded, but the polychromatic scheme of the interior is still pronounced and impressive. Although much of the ironwork has been replaced, gilded balustrades and railings would have added to the opulence of the Terminus in its early years.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Dikshagusain718, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Progress

With its muted Indic features (domes, ornamented squinches, and chaitya arches), the Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus embraces an eclectic Gothic style that is a valuable example of the Indo-Sarascenic—in the selective utilization of Indian architectural precedents, the selective representation of India, and in the framework of empire on which the design of the building is predicated.

For the British Raj, the city of Bombay was their mercantile jewel and they were as confident in their self-perceived role as the city’s visionaries as the allegorical figure of Progress atop the Terminus. Today, the Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus is an emblem of change and it has pride of place at the heart of the city. It is a historical landmark, a UNESCO world heritage site, and an important resource for the millions of people who regularly use it.

Progress now looks over a city transformed, an empire dismantled, and the world’s largest democracy.

Notes:

[1] In 1803, when the 1st Marquess Wellesley, a colonial administrator in Calcutta was called to task for the amount he spent on building the Government House in Kolkata, he responded that India “ought to be ruled from a palace, not from a country house; with the ideas of a prince, not those of a retail dealer in muslins and indigo.” See The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1809 (London: J. Dodsley, 1809), p. 813.

[2] Christopher London, Bombay Gothic (Mumbai: Jaico, 2002), p. 93

[3] ibid., p. 90.

References:

Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon, 1997).

Stephen Goodwin Howard, “Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai.” MA Dissertation, University of York, Department of History (2012).

Christopher London, Bombay Gothic (Mumbai: Jaico, 2002).

Additional resources: