Neolithic China: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 6

Death and material culture in early China

Introduction

As early as the Neolithic period, people living in what we now know of as China were preoccupied with separating the world of the living from the world of the dead. Along with this came a desire to equip the dead, buried carefully in underground tombs, with offerings of pottery vessels or jade ornaments that would aid them in the unknown world of the beyond—an afterlife that would later be described by Warring States period writers as permeated with dangerous environmental forces and rapacious, soul-consuming monsters. Underground tombs served to protect the remains of the dead and offered their spirits a permanent abode for the afterlife.

One-tier tube (cong 琮) with masks, a common funerary object, Liangzhu culture 良渚, Late Neolithic period, c. 3300–c. 2250 B.C.E., jade (nephrite), China, Lake Tai region, 4.5 x 7.2 x 7.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art)

In this chapter, we examine 5,000 years of early Chinese funerary art, from the Neolithic period through the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. to 220 C.E.), and across the diverse geographical and cultural landscape of early China. Over this period, we see abodes for the dead evolve from simple earthen vertical pit tombs with a few pottery vessel offerings to multi-chambered underground or hillside tombs furnished with objects made from a variety of materials such as bronze, lacquer, jade, silk, bamboo, and clay. Most of our knowledge about early China is derived from tomb excavations and the wealth of artifacts they have yielded. These discoveries give us important insight into early Chinese cultures and societies: how they were organized, their belief systems, the diversity of their regional and cultural identities, and the materials and sophisticated technologies they employed. Through a close study of the material remains of these distant peoples, their stories come to life, and we realize our shared awareness of our mortality and our never-ending quest for longevity.

Neolithic

In China, hunters and gatherers settled down into agricultural villages around 7,000 B.C.E. With this transition, people had more time to devote to craft specialization. As you will read in the Neolithic period essay below, although Neolithic people did not leave behind written records, we can piece together their stories from the archaeological record in their villages, including building foundations and cemeteries, and artifacts made of pottery, jade, and bone.

Read an introductory essay

/1 Completed

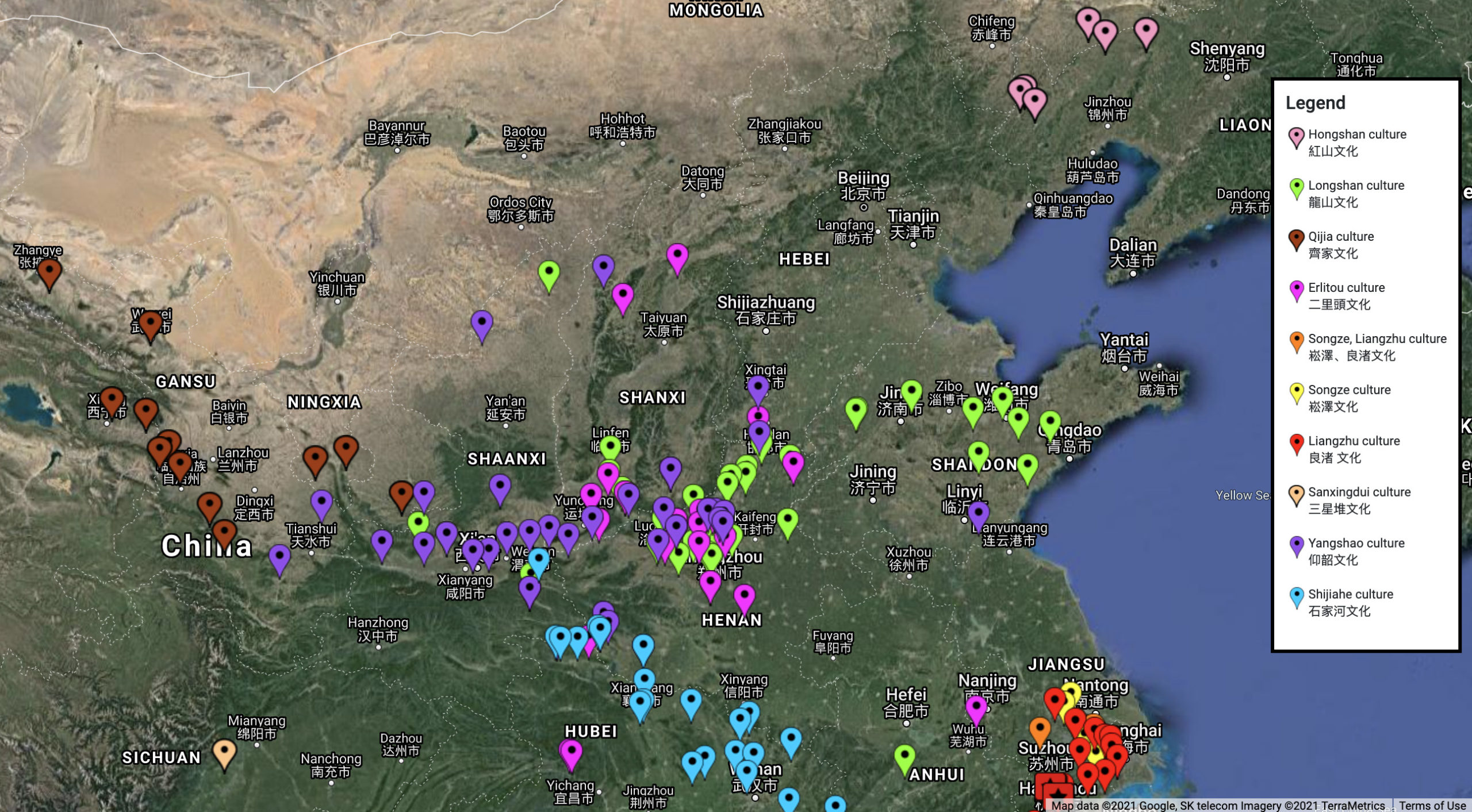

Map of Neolithic China, with hotspots corresponding to published excavations. Different hotspot colors represent the different cultures revealed. See a responsive map here (underlying map © Google)

As seen in the map above, China experienced numerous “Neolithic Revolutions” simultaneously and, as one might expect, we see distinct differences in burial rites from one Neolithic cultural group to the next. In this section, we will explore three cultural groups that help characterize the diverse burial practices across China during the Neolithic period: Yangshao culture along the Wei River in central China, Longshan culture along the east coast, and Liangzhu culture in the southeast.

During the Neolithic period in China, settled agricultural peoples took an interest in separating the everyday workings of village life from the cemeteries of their dead.

Yangshao culture

At Yangshao cultural sites like Banpo (situated along the Wei River), the cemetery was located beyond a deep ditch surrounding the village. The dead were buried in simple vertical earthen pit tombs with a few pottery vessels as offerings. At Yangshao sites vessels made for food offerings were preferred over vessels for liquid offerings. Clay vessels, made by hand using the coil technique, were used to store these offerings.

Pot with fish designs, Yangshao culture, 5th–4th millennium B.C.E., Neolithic period, from Banpo, China (National Museum of China; photo: Zhangzhugang, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Yangshao cultural sites like Banpo are often referred to as painted pottery cultures to distinguish them from the so-called black pottery cultures of the east coast. However, at Banpo only a small percentage of pots were painted, and they were found exclusively in burials. Banpo painters mainly decorated funerary vessels with geometric motifs, including abstract triangles and geometric fish. This comes as no surprise considering Banpo’s location, but can you think of other reasons why images of fish on funerary vessels might be significant?

Longshan culture

At Longshan culture sites on the east coast the dead were buried beyond the pounded earth walls of their villages. While some Longshan peoples were buried in simple earthen pits without offerings, others were buried in wooden coffins in pit tombs constructed with a burial ledge for the placement of offerings. These included pottery vessels in a variety of shapes from bowls and tripods to pouring jugs and fragile goblets.

Stem Cup, Longshan culture, c. 2500–2000 B.C.E., burnished earthenware, China, 22.7 x 8.41 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Different from Yangshao culture, Longshan culture favored liquid vessel offerings over food vessels for the funerary ritual. Vessels were made on a wheel, with the most distinctive being elegant drinking goblets with walls as thin as eggshell and fired in a reducing atmosphere to transform the red iron oxide in the clay into black iron oxide.

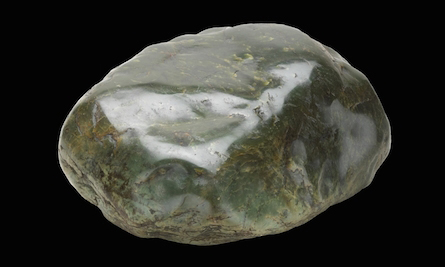

A distinctive feature of Chinese Neolithic cultures along the east coast and in the northeast is their production of jade artifacts.

Liangzhu culture

At Liangzhu culture sites, jade objects carved into round discs (bi), square tubes with circular inner hollows (cong such as the one shown earlier), and axes (yue) were carefully placed on and around the bodies of the deceased.

Hongshan culture

Further to the northeast, jade carved into such shapes as coiled dragons, stylized clouds, and hoofs ornamented the bodies of the dead at Hongshan. Jade is a material that is associated with wealth and status. In the following essays, you will learn more about jade in Neolithic China and how this material was worked. What processes are involved in the making of a jade object that add to its value?

Essays and videos about jade

Jade cong: These enigmatic, rectilinear tubes reveal clarity of thought and took great effort to produce.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Shang Dynasty

Map of the Shang dynasty with the last Shang dynasty capital at Anyang (underlying map © Google)

Around 1600 B.C.E, civilization emerged along the Yellow River and in other regional centers across China. Neolithic agricultural peoples who once lived in small villages transitioned into cities with increased social stratification. With this transition, came the introduction of bronze metallurgy and writing. The Bronze Age civilization situated near the Yellow River in north China was ruled by the Shang, a powerful ancestor-worshipping culture.

In the Shang dynasty introduction essay below, you will read about Shang ritual practices, the written records they left behind on oracle bones, and how they used bronze to cast vessels to make offerings to the ancestral spirits.

An introductory essay

Shang dynasty, an introduction: Learn about how the Shang people left many legacies for later generations in China

Read Now >/1 Completed

With the rise of cities, increased social stratification, writing, and the use of metallurgy during the Shang dynasty, we see the construction of highly sophisticated tombs for the elite. Although Shang civilization has its origins in the Yellow River Valley, elements of Shang grave construction can be traced back to East Coast Neolithic sites. This includes construction of burial ledges at the bottom of deep earthen shaft tombs for the placement of burial offerings, which, in the case of the Shang, included human sacrifices and objects made from a variety of materials: bronze, jade, bone, lacquer, and clay.

Kneeling figure, jade pei, from the Tomb of Fu Hao (Tomb 5 at Xiaotun), late Shang dynasty, 1200 B.C.E., Yinxu, Anyang, Henan, China

Unfortunately, the tombs of the Shang kings buried in the royal cemetery at the last Shang dynasty capital at Anyang were looted in antiquity, but the tomb of the warrior queen Fu Hao, examined in this section, gives us important insight into elite Shang burial rites. The discovery of Fu Hao’s tomb and its material remains helped corroborate inscriptions written on oracle bones that detailed the exploits of this mighty female general and mother to the heir to the throne. How were oracle bones used? What do we learn about Fu Hao and Shang civilization from inscriptions on the bones?

Essays and videos about Shang tombs

Oracle bones: The writing on these bones is 3000 years old, but scholars can decipher an incredible 40 percent of the characters.

Read Now >

The Tomb of Fu Hao: This tomb confirmed Fu Hao’s role as one of the most important female military commanders of ancient China.

Read Now >/2 Completed

In elite burials like Fu Hao’s, bronze ritual vessels were among the most important offerings to the deceased. Cast using the section mold technique unique to ancient China at the time, Shang bronze vessels are extraordinary examples of ancient design thinking. The essay and video below explore an example of a Shang guang vessel cast with a lid in the shape of a fantastic horned animal and adorned with detailed surface decoration. How did vessels like this one function in the life and death of a Shang elite? How would you describe the surface decoration?

Read an essay and watch a video about a bronze vessel

Tigers, dragons, and, monsters on a Shang Dynasty Ewer: This container was one of many that was used to hold wine, water, grain, or meat in sacrifices to ancestors or in ritual banquets by Shang kings.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Zhou Dynasty

Around 1050 B.C.E. the Zhou ruling family, whose homeland was in the Wei River Valley near modern-day Xi’an, in Shaanxi province conquered the last Shang dynasty capital at Anyang. The succeeding Zhou dynasty can be divided into two periods: the Western Zhou (1050–771 B.C.E.) and the Eastern Zhou (771–221 B.C.E.) based on the location of the Zhou capital. In the Zhou dynasty introductory essay below, you will read about the Zhou consolidation and subsequent loss of centralized power, which eventually led to the rise of independent kingdoms and a flourishing of regional arts and intellectual thought during the Eastern Zhou period.

When Zhou authority weakened during the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771–221 B.C.E.) and independent kingdoms arose across the ancient Chinese landscape, we start to see significant changes in how precious materials were distributed, acquired, and used by the elite. Whereas during the Shang dynasty the use of bronze was controlled by kings, during the Eastern Zhou anyone with the wealth to afford this precious material could cast bronze objects. Instead of ritual vessels cast for use in ancestor worship rituals and then buried in tombs, bronze was used as a display of material wealth and status in life and in death.

This is exemplified in the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng, excavated at Leigudun, in Sui County, Hubei province discussed in the essay below. Marquis Yi’s tomb yielded a tour de force of bronze casting. The marquis was buried with bronze vessels decorated with ornate sculptural forms, as well as a highly sophisticated set of 64 perfectly tuned musical bells, all of which employed casting technologies both new and old. The marquis’s tomb and the offerings placed inside are an extravagant display of Zeng culture and the marquis’s life of luxury, which his spirit continued to enjoy in his multi-chambered tomb in the afterlife. How does the marquis’ tomb and the objects placed inside reflect his ambition and status? What can we learn from the tomb about regional politics and trans-regional connections during the Warring States period?

Read about the marquis's tomb

The tomb of the Marquis Yi of the Zeng State: Massive burial chambers, gigantic double coffins, grand bronze vessels, and chime bells are found in this tomb.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Qin Dynasty

In 221 B.C.E., the king of the Qin state unified the independent kingdoms of the Eastern Zhou period and declared himself “First Illustrious Emperor,” or Qin Shi Huangdi, of the Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.) ushering in a new era of imperial rule of China. In the Qin dynasty introductory essay below, you will read about the First Emperor’s many accomplishments, which culminated in his massive mausoleum.

Read an introductory essay

Qin dynasty, an introduction: The state of Qin was China’s first unified state whose power was centralized instead of spread among different kingdoms in the north and south.

Read Now >/1 Completed

The Tomb of the First Emperor

In this section, we examine the Mausoleum of the First Emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi and the terracotta warriors discovered near his tomb. In the history of ancient Chinese tomb construction, the First Emperor’s tomb complex is unprecedented in scale.

An idea of the size of the complex can be gained when viewing the pyramid-shaped tumulus and the Army Pits, currently the site of the Museum of the Tomb of the First Emperor, which are 1.22 km/0.75 miles away from each other (underlying map © Google)

Although the tomb proper—buried under a massive tumulus—has not been excavated, pits within the walled mausoleum and beyond have yielded astonishing discoveries. How does the scale of the First Emperor’s tomb complex compare to tombs of earlier periods? What types of discoveries were made at the First Emperor’s vast tomb complex? How do these discoveries help us understand how the First Emperor conceived of the afterlife?

Read an overview essay

Tomb of the First Emperor: Qin Shi Huangdi, the first unifier of China, is buried at the center of a complex designed to mirror the urban plan of the capital, Xianya.

Read Now >/1 Completed

An Army for the Afterlife

During the Warring States period and after the time of Confucius we begin to see the practice of replacing human sacrifices in tombs with miniature figurines, carved out of wood, painted, and sometimes enlivened with real human hair. This practice continued during the Qin dynasty, but tomb figurines excavated in pits near the tomb of the First Emperor were enlarged to an extraordinary life-size scale and crafted in terracotta to represent a diverse cross-section of Qin society. In the history of Chinese archaeology, realistic, life-sized representations of human figures like these had never been seen before.

Pit #1, Tomb of the First Emperor, Qin dynasty (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The emperor took life-like terracotta replicas of his army, officials, entertainers, attendants, grooms, and undoubtedly more yet to be discovered, into the afterlife with him. Where did the idea for life-size sculptures of human figures come from? Did trade via the Silk Routes inspire the construction of these figurines? The figurines, especially the terracotta army, are often described as portraits of individual soldiers that served the First Emperor in his lifetime, but is this a carefully crafted illusion? How were these life-like figurines made and how did they function in the afterlife of the First Emperor?

Read about the emperor's army

The terracotta warriors: Like characters in a play, the terracotta figures were created to enact a part of the world of the First Emperor in the afterlife.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Han dynasty

After the death of Qin Shi Huangdi (founder of the Qin dynasty) in 210 B.C.E., China fell into chaos, until being reunified under the Han dynasty. In the Han dynasty introduction essay below, you will read a brief history of this period, including an introduction to the different types of objects found in Han tombs and the new ways ancient materials like bronze, jade, and clay were used to aid Han tomb occupants on their journeys into the afterlife.

Read an introductory essay

Han dynasty, an introduction: It was a pivotal period in the history of China—many foundations were laid for enduring aspects of Chinese society.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Tomb excavations have revealed that during the Han dynasty there was a revival of the diverse regional cultural traditions and religious practices of the Eastern Zhou period that had been suppressed during the Qin dynasty. This is evident in the variety of local burial customs seen across the Han realm, but as noted in the introductory essay linked above, Han burial practices expanded on earlier precedents in the desire to model the world of the living for the afterlife of the dead. This is seen in both the construction of Han tombs, as well as in the types of offerings made to the tomb occupant. In Han tomb construction, we see tombs modeled on above-ground palaces or divided into chambers according to function.

Black outer coffin, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., lacquered wood (Hunan Provincial Museum)

One of the best-preserved examples of the latter is the tomb of Lady Dai excavated at Mawangdui, in Changsha, Hunan province far from the imperial capital at Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an). How does the tomb of a Han aristocratic woman compare or contrast to the multi-chambered tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng from nearly 300 years earlier?

As seen in Lady Dai’s tomb, Han tombs were filled with a variety of objects including everyday objects the tomb occupant owned, used and cherished while they were alive, and mingqi 冥器 “spirit objects,” or replicas of everyday people or objects made specifically for use in the afterlife. The former category included anything from lacquered cosmetics boxes and kitchenware to silk clothing and heirloom objects.

Lamp, Western Han dynasty, gilt bronze, excavated from the tomb of Dou Wan (竇綰) in Mancheng county, Hebei province, 48 cm high (Hebei Provincial Museum, China; photo: Gary Todd, CC0)

The tomb of Princess Dou Wan, which is roughly contemporary with Lady Dai’s and was discovered at Lingshan, Mancheng, in Hebei province, yielded an example of a treasured heirloom with a gilded bronze lamp in the shape of a kneeling servant girl. Inscriptions on this functional lamp, in which the figure’s right sleeve serves as a chimney, trace the history of this precious object, suggesting it was a gift to the princess from the Empress Dowager (her husband Liu Sheng’s grandmother).

Examples of mingqi: clay replicas of coins (left) and painted tomb figurines made of wood (right), Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (Photos by Gary Todd).

In the category of mingqi we also see a wide variety of objects, made from a variety of materials. Some are made of inexpensive, easily accessible materials like clay and wood, while others are made of precious materials like lacquer, silk, and jade, all of which required significant time and labor to produce. In Lady Dai’s tomb, her inventory of spirit objects included inexpensively made figurines of servants carved from wood to substitute for human sacrifices. Her tomb also included spirit objects as precious as Dou Wan’s gilt bronze lamp, such as her exquisitely painted lacquered coffins and her personalized silk narrative banner painted with rich mineral pigments found draped over her innermost coffin. In the case of Lady Dai, these spirit objects served the same function: to aid Lady Dai in the afterlife and to help her reach her final destination. How is Lady Dai’s journey from the earthly world to the heavenly realm depicted on the silk banner? How does the artist help us follow the narrative of Lady Dai’s ascension?

Read essays about the Tomb of Lady Dai

The funeral banner of Lady Dai: Excavated from an ancient tomb, this opulent silk banner features the earliest known portrait in Chinese painting.

Read Now >/2 Completed

From the examples of tombs and funerary art explored in this chapter, we can see that providing for the dead and their continued existence in a spirit world is an overriding theme in the visual and material culture of early China, especially for the elite who could afford the luxury of a well-endowed afterlife. The making and offering of special provisions for the dead still continues to this day in the much more accessible and affordable burning of paper money and papier-mâché objects (including paper Pfizer vaccines!) at modern funeral ceremonies to create spirit copies of everyday objects, not unlike the mingqi of the distant past.

Key Questions

What can we learn about ancient Chinese belief in the afterlife from the excavation of ancient tombs?

How did the ancient Chinese concept of the afterlife change over time?

What can we learn about the significance of materials, such as bronze, jade, silk, lacquer and clay from objects buried in ancient Chinese tombs?

How was status represented in the burial of the dead in ancient China?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat can we learn about ancient Chinese belief in the afterlife from the excavation of ancient tombs?

How did the ancient Chinese concept of the afterlife change over time?

What can we learn about the significance of materials, such as bronze, jade, silk, lacquer and clay from objects buried in ancient Chinese tombs?

How was status represented in the burial of the dead in ancient China?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Neolithic period

pit tomb

coil technique

Yangshao culture

Longshan culture

Linagzhu culture

bi

cong

yue

jade

Yellow River Valley

Bronze Age

Shang dynasty

oracle bone

taotie

Fu Hao

guang

Zhou dynasty

Confucianism

Daoism

piece-mold casting

Warring States Period

Qin dynasty

imperial China

Qin Shi Huangdi

terracotta

Silk Road/Silk Routes

Han dynasty

mingqi

lacquer