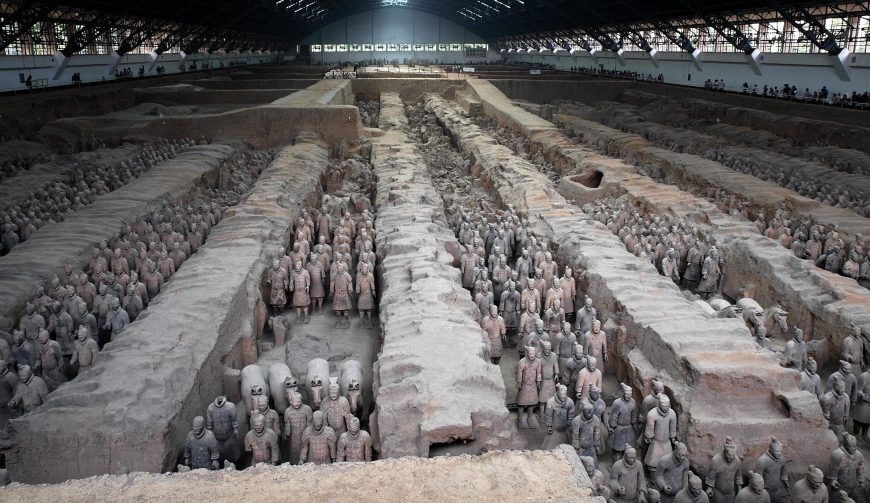

Pit 1, Army of the First Emperor, Qin dynasty, Lintong, China, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: mararie, CC BY-SA 2.0)

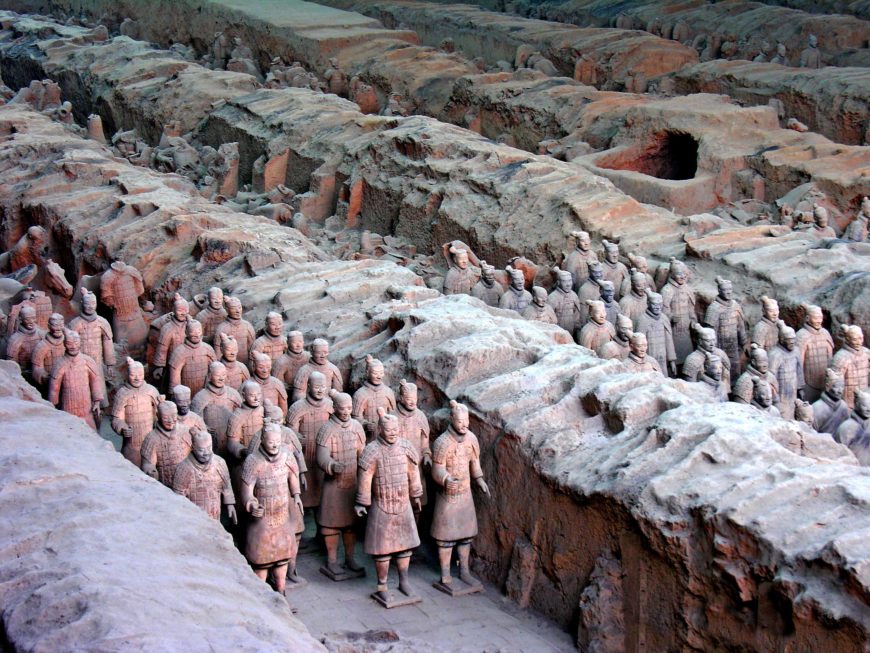

The Tomb of the First Emperor of China was accidentally discovered in 1974 when farmers digging for a well found several ceramic figures of warriors. As the discovery quickly garnered national attention, archaeological investigation revealed three large underground chambers (referred to as “pits”) containing shattered fragments of terracotta warriors. These life-sized, life-like ceramic figures depict warriors, with every detail of their dress skillfully rendered, and still bearing traces of their original paint at the time of their discovery. The terracotta warriors looked unlike any tomb figures that had been known before. What is more, pits 1, 2, and 3 were only a small part of what turned out to be the massive tomb complex of the First Emperor.

View of the soldiers at their discovery (The Museum of Qin Terra-cotta Warriors and Horses, Xi’an; photo: edward stojakovic, CC BY 2.0)

Animated map of the Warring States period (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The First Emperor (born Ying Zheng), initially ruled as the king of the Qin state. Through forceful military campaigns, he conquered the states occupying much of the current territory of China, bringing an end to the Warring States Period. He reformed the culturally and politically distinct states into a single, centralized political entity.

In 221 B.C.E., he officially declared himself Qin Shi Huangdi, a title he coined himself commonly rendered as the “First Emperor” that literally translates to “First August Emperor of Qin.” This was no empty gesture—the First Emperor’s reforms and unification would forever change the meaning of rulership in East Asia.

Among his monumental building projects was a monumental tomb of unprecedented splendor, whose scale and luxury became, with the passage of time, the matter of legend. Nevertheless, none of the fantastic tales found in the written record prepared archaeologists for what they would find in the Mausoleum of the First Emperor.

Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi in 2010 (photo: 申威隆, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The tomb complex of the First Emperor

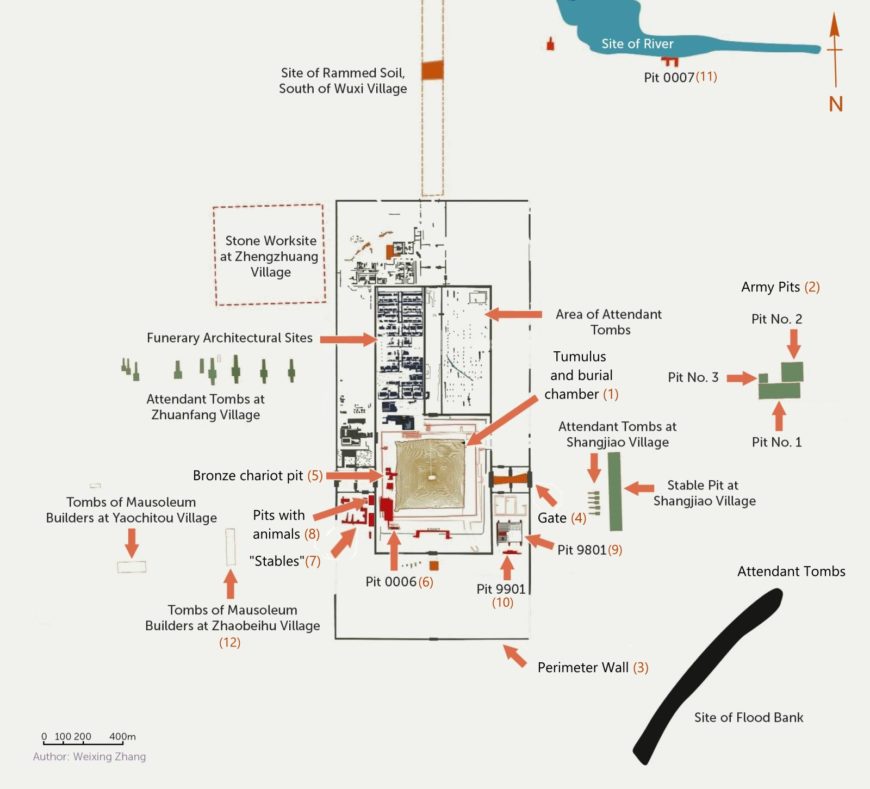

The mausoleum is a vast tomb complex which covers an area of 6.3 square kilometers or 3.9 square miles, and which is centered around a tumulus (at no. 1 in the diagram below). Dominating the landscape, the tumulus was long known to mark the burial place of the First Emperor, but the scale of the underground complex was unknown before the discovery of the three pits (called the Army Pits).

The First Emperor’s tomb complex is often called a mausoleum (no. 2 in the diagram below), but this does nothing to convey the scale and complexity of the network of pits, accompanying tombs, and above-ground structures that surround the burial chamber under the tumulus. For instance, the Army Pits are .75 miles away from the mausoleum! After more than 30 years of excavation, starting with the original discovery in 1974, only a fraction of the full extent of the complex has been excavated, with new discoveries being made every year.

Diagram of the tomb complex, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi (diagram Weixing Zhang; modified by Alexandra Nach). The pyramid-shaped tumulus and the Army Pits, currently the site of the Museum of the Tomb of the First Emperor, are 1.22 km/0.75 miles away from each other. Each of the pits and objects discussed in this essay are labeled with orange numbers.

Two above-ground walls (no. 3 on the diagram) formed the perimeter of the tomb complex (which included the tumulus). Originally the walls were 10m thick, and were pierced by monumental gateways (no. 4 on the diagram) that no longer exist though the openings remain visible. The burial mound occupies the southern side of the walled enclosure, while the northern side is split between a walled-off section containing 34 unopened companion tombs and a complex of above-ground ritual buildings (no longer standing) where sacrificial rites were performed for the deceased emperor as part of rituals of ancestor worship. A vast underground complex—encompassing a network of pits and smaller tombs of humans and animals, as well as underground walls and drains ensuring the stability of the structure—stretches underneath the walled enclosure, as well as beyond it.

Beneath the tumulus lies the burial chamber of the First Emperor. It has not yet been excavated, primarily out of concern for properly preserving its contents during excavation. However, using scientific surveying methods such as magnetic anomaly surveying, archaeologists have been able to identify the location and size of the burial chamber, and discover that subterranean walls of brick and tamped earth surround the tomb chamber to protect it from being flooded by the high water table.

One important written source, the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian) written by Sima Qian around. the year 94 B.C.E., gives us a description of the burial chamber:

Replicas of palaces, scenic towers, and the hundred officials, as well as rare utensils and wonderful objects, were brought to fill up the tomb. […] Mercury was used to fashion imitations of the hundred rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangtze, and the seas, constructed in such a way that they seemed to flow. Above were representations of all the heavenly bodies, below, the features of the earth. Quoted in Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty by Burton Watson, p. 63

As tantalizing as this passage is, it should be read with some caution. Sima Qian was writing a history for the dynasty which conquered that of the First Emperor, and more than a century after his death. While Sima Qian remains a major source of information on the First Emperor and his tomb, the author consistently sought to depict him as a tyrannical, excessive ruler. We may not know for certain whether the tomb vault contains rivers of mercury and a dome depicting the celestial vault—however the passage has provided scholars with important clues on how to understand the different pits and spaces in the tomb complex. Sima Qian describes a tomb complex that aims to replicate the buildings, geographic features, imperial possessions, and the very inhabitants of the Qin Empire.

This is a dramatic development in how Chinese tombs were conceived. Since the early Bronze Age, Chinese ruling elites had taken bronze ritual vessels, ceremonial musical instruments, and chariots with sacrificed horses into their tombs. By the Qin dynasty, all of these items had become established symbols of rulership. In the Warring States period preceding the First Emperor’s unification, rulers had begun to segment their tombs into compartments resembling rooms, indicating a shift towards imagining the tomb as a replica of a dwelling, or even a palatial compound. But nothing comes close to the all-encompassing program of the First Emperor’s tomb. Where earlier rulers had been content to bring their valued weapons, ritual vessels, and horses with them into the afterlife, the First Emperor re-created entire stables and garrisons, and enlivened them with terracotta figures performing the everyday tasks of government.

What follows are descriptions of several of the most important archaeological finds in the tomb complex, each interpreted as a recreation of the world of the First Emperor within the space of his mausoleum.

Getting around

War Chariot (first chariot), Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, c. 210 B.C.E. (photo: Tiffany, CC BY-NC 2.0)

One important find within the perimeter of the walls is a 50-meter-long pit containing two bronze chariots (no. 5 on the diagram) one bearing a canopy and one a closed compartment. Both vehicles faithfully replicate every component of a wooden chariot— but in bronze, and at a scale of half the size of their real-life wooden counterparts. The chariot with the canopy is manned by a figure equipped with a crossbow, and is positioned in front of the second vehicle.

Second Chariot, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, c. 210 B.C.E. (photo: Gary Todd)

The second chariot is driven by a kneeling figure and features a closed compartment with windows and a sloping roof. Elaborate cloud and lozenge patterns painted on the bronze walls of the compartment are still visible. This lavish chariot matches the descriptions of the vehicles employed by the Emperor during his tours of the empire, leading archaeologists to suggest the bronze chariots are models of the First Emperor’s actual vehicles. As tempting as it is to imagine the spirit of the Emperor journeying in these carriages, where he would journey to is hotly debated. Researchers have suggested that the chariots might carry the emperor to a distant afterlife or could help him retrace his imperial tours after his death. Others have suggested they could simply carry his spirit to the recreation of his pleasure gardens at the far side of the tomb complex.

Getting things done in the empire

Another pit (no. 0006; no. 6 on the diagram) housed twelve terracotta figures dressed in long coats with broad sleeves and distinctive headgear identifying them as officials—their coats even show tools for correcting writing errors on bamboo. They represent the bureaucracy that ran the Empire.

The Emperor’s menagerie

Terracotta attendant found in the animal burial pits (photo: Gary Todd)

One large pit to the west of the inner wall contains hundreds of sacrificed horses (no. 7 on the diagram), assumed to have belonged to the imperial stables. Other smaller pits nearby contain individual animals, including exotic breeds of deer and birds, all in ceramic caskets. These are assumed to be from the Emperor’s zoo. The remains of the animals were guarded by ceramic attendants and grooms (no. 8 on the diagram). While sacrificing horses for the burial of elites was a long established practice in China, the First Emperor’s mausoleum surpasses all earlier tombs through the sheer number of animals sacrificed. The presence of grooms and terracotta attendants turns a burial into a recreation of the space of the stable—archaeologists even found traces of hay on the floor.

Otherworldly armor

Lamellar armor found in Pit No. K9801 (photo: anokarina, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Meanwhile, pit K9801 on the eastern side (no. 9 on the diagram) contains another mystery—87 sets of armor, each made out of 80 small stone plates connected with bronze wire, as well as helmets made the same way. Each set of this otherworldly armor was too heavy and constrictive to have ever been used in combat. Why was this armor made out of stone, rather than clay or other materials?

Starting from the 4th century B.C.E., Chinese tombs often included copies of everyday objects purposefully made out of the “wrong” material, referred to as mingqi (translated as “spirit articles”). However, stone armor plates are unique to the tomb of the First Emperor, and these are the only articles in the tomb to be made out of stone.

One theory argues that stone was thought at the time to have apotropaic (meaning that it could ward against ghosts and evil spirits) properties. The stone armor, so the argument goes, was provided in case the faithful terracotta warriors would have to face off against a supernatural threat against the First Emperor’s spirit—perhaps even the angry ghosts of his former enemies.

Entertainers

Figure of the “strongman” from Pit K9901 (photo: Gary Todd)

One of the most spectacular finds is a pit K9901 (no. 10 on the diagram) containing half-clothed figures, each unique and with differing physiques. One (known as a “strongman”) flexes his strong arms and muscular shoulders, as if tugging on a weight. These figures are commonly known as the “Acrobats,” thought by some to represent a troupe meant to provide entertainment for the Emperor in his afterlife.

Other explanations, however, have been offered, such as the bare-chested figures representing soldiers in training, or figures engaged in a competition of “cauldron lifting.” The presence of a massive and beautifully cast cauldron in the same pit could be explained by this theory. Scholars have argued that such weight-training competitions involving lifting heavy bronze cauldrons, which often took place at autumn religious festivals, functioned as a display of both physical prowess and military might.

Outside the rectangular walls of the tomb precinct, other finds connected to the tomb have been excavated. A trench covers the length of the F-shaped pit K0007 (no. 11 on the diagram), its floor covered in mud, indicating its function as a water basin. It was surrounded by ledges on which bronze waterfowl were perched. On make-shift windows in the pit there are also kneeling figures who likely once held wooden instruments —entertainers in an underground garden.

Imperial parks, large enough to hold hunting parties, were an important symbol of royal power for Chinese rulers. Scholars have identified a high terrace known as Hongtai, the “Terrace of Wild Swans,” built for the Emperor to shoot wildfowl from the park of one of his palaces as a potential inspiration for Pit K0007.

Companion tombs

Both inside and outside the tomb precinct, a large number of other tombs have been found. The tombs inside the precinct, though not yet opened, could possibly belong to concubines and close relatives of the First Emperor—written records suggest that some offered to join their Emperor in death, while others were forced to.

Meanwhile, several hundred much plainer tombs have been found (located by the current-day Zhaobeihu Village, no. 12 on the diagram, west of the walled burial complex) that contain the remains of the prisoners and laborers forced to work on the tomb. Some of these tombs contain small ceramic fragments that indicate the name, hometown, rank, and sometimes in the case of prisoners, what their punishment was. Incision marks on bones found in these tombs attest to the severe physical punishment suffered by some of the builders. The remains of women and children were also found, possibly victims of the principle of kin liability practiced by the Qin, which stipulated that the entire family be punished for the crime of one member. The remains of the laborers remind us of the human cost of the tomb’s magnificence.

Pit 1, 230m/754 feet long, 62m/203 feet wide and dug 5m/16.4 feet deep into the ground, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, c. 210 B.C.E. (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Army Pits and the Terracotta Warriors

The three pits known as the Army Pits (no. 2 on the diagram, and includes Pit nos. 1, 2, and 3) are by far the most famous. The thousands of warriors found inside were accompanied by wooden chariots and terracotta horses. Each of the ceramic figures bears individually modeled armor, hairstyles, and headdresses that make every figure stand out as unique, and allow distinction between the ranks of the soldiers and their different roles in an army—from archers to infantrymen to charioteers. Showing such a vast army, exemplifying the military dominance of a state that depended on being able to assemble the largest numbers of warriors.

The image of an Emperor

As we have seen, the tomb of the First Emperor is unique in Chinese history in its scale and its use of detailed, life-scale figures. However, we can only speculate as to how the tomb actually “worked.” Was it meant to serve as a literal resting place for the First Emperor’s soul, where the skillfully rendered servants and soldiers would become enlivened to serve the deceased ruler in the tomb? Or would the magnificent underground palace only serve as a temporary abode that the spirit of the Emperor would regularly return to in order to receive the sacrifices performed in the temples surrounding the burial mound? Or did the elaborate pits and spaces of the tomb complex provide a “model” for the afterlife that the spirit of the First Emperor would be traveling to?

Modern statue of Qin Shi Huang in front of the Museum of the Terracotta Army (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Unfortunately, we do not have any clear textual account of how the Emperor and the people of his time conceived of the afterlife. Both archaeological and textual evidence points to an increased tendency to see the space of the tomb as an afterlife abode resembling the space of the living where the dead could rest and receive the offerings of the living. However this was only one idea of the afterlife among many, and researchers still dispute these issues. The tomb of the First Emperor is both the most important body of archaeological evidence for a momentous change in Chinese funerary culture, and a great open question as to how we can interpret it.

The Emperor himself is absent from his own tomb and army. Even though a modern statue of the great ruler stands before the Museum of the Terracotta Army, it is not based on an excavated figure. We lack his voice, and his intent. The closest we have to his vision in own words is the later records of stele inscriptions he set up. In these inscriptions he details his ideology of government. A stela at Mt. Zhifu reads:

The Great Sage creates His order, Establishes and fixes the rules and measures, Makes manifest and visible the line and net [of order].…The six kingdoms had been restive and perverse, Greedy and criminal, insatiable – Atrociously slaughtering endlessly. The August Emperor felt pity for the multitudes, And consequently sent out His punitive troops, Vehemently displaying His martial power.

Trans. Martin Kern, Imperial Tours and Mountain Inscriptions, p.110, in Jane Portal ed, The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army (Cambridge 2007)

The First Emperor saw himself not only as a great conqueror but as someone who saw it as his mission to establish a new sense of order in the world he governed. In this sense, the Terracotta Army and the terracotta officials and servants embody his vision as a representation of an ordered administration, as well as a monumental ensemble of sculptural figures whose every part was made to an ordered standard. They represent not only the “martial power” required to unify an empire: more than anything, they are a powerful statement about the Emperor’s vision of what can be accomplished in a realm unified under his direction. Even though we may never know how the Emperor planned to spend his afterlife in his underground palace, he encoded his vision in a mausoleum that shocks and awes us to this day.

Additional resources:

Ladislav Kesner, “Likeness of No One:(re) presenting the First Emperor’s army,” The Art Bulletin vol. 77, no. 1 (1995), pp. 115-132.

Maria Khayutina, Qin: the eternal emperor and his terracotta warriors (Zurich: Neue Zürcher Zeitung Publishing, 2013).

Lothar Ledderose, Ten thousand things: module and mass production in Chinese art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Jane Portal and Hiromi Kinoshita,The first emperor: China’s Terracotta Army (Atlanta, GA: High Museum of Art, 2008).

Lukas Nickel, “The first emperor and sculpture in China,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. University of London vol 76, no. 3 (2013): p. 413.

Hung Wu, “On tomb figurines: The beginning of a visual tradition,” in Body and Face in Chinese Visual Culture (Brill, 2005), pp. 11-47.

No doubt thousands of statues still remain to be unearthed at this archaeological site, which was not discovered until 1974. Qin (d. 210 B.C.), the first unifier of China, is buried, surrounded by the famous terracotta warriors, at the centre of a complex designed to mirror the urban plan of the capital, Xianyan. The small figures are all different; with their horses, chariots and weapons, they are masterpieces of realism and also of great historical interest.