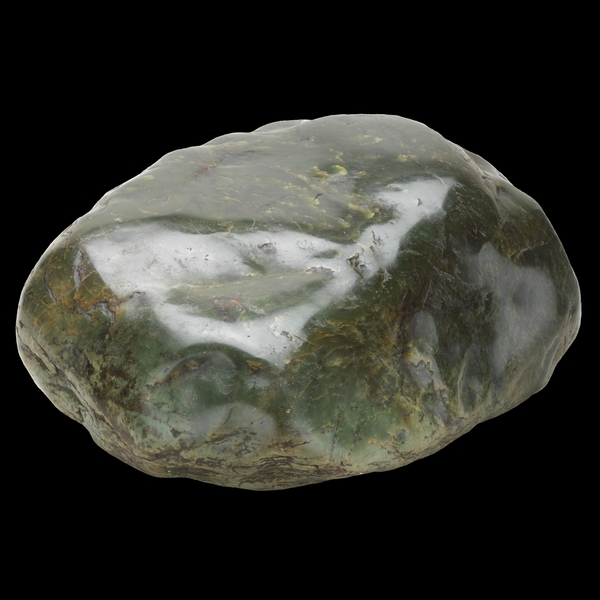

Jadeite (© 2003 Private Collection, © Trustees of the British Museum)

What is jade?

The English term “jade” is used to translate the Chinese word yu, which in fact refers to a number of minerals including nephrite, jadeite, serpentine and bowenite, while jade refers only to nephrite and jadeite.

Chemically, nephrite is a calcium magnesium silicate and is white in color. However, the presence of copper, chromium and iron produces colors ranging from subtle grey-greens to brilliant yellows and reds. Jadeite, which was very rarely used in China before the eighteenth century, is a silicate of sodium and magnesium and comes in a wider variety of colors than nephrite.

Nephrite (© 2003 The Natural History Museum Nephrite, © Trustees of the British Museum)

Nephrite is found in metamorphic rocks in mountains. As the rocks weather, the boulders of nephrite break off and are washed down to the foot of the mountain, from where they are retrieved. From the Han period (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) jade was obtained from the oasis region of Khotan on the Silk Route. The oasis lies about 5000 miles from the areas where jade was first worked in the Hongshan (in Inner Mongolia) and the Liangzhu cultures (near Shanghai) about 3000 years before. It is likely that sources much nearer to those centers were known about in early periods and were subsequently exhausted.

Worn by kings and nobles in life and death

“Soft, smooth and glossy, it appeared to them like benevolence; fine, compact and strong – like intelligence” —attributed to Confucius (about 551–479 B.C.E.)

Jade has always been the material most highly prized by the Chinese, above silver and gold. From ancient times, this extremely tough translucent stone has been worked into ornaments, ceremonial weapons and ritual objects. Recent archaeological finds in many parts of China have revealed not only the antiquity of the skill of jade carving, but also the extraordinary levels of development it achieved at a very early date.

Jade was worn by kings and nobles and after death placed with them in the tomb. As a result, the material became associated with royalty and high status. It also came to be regarded as powerful in death, protecting the body from decay. In later times these magical properties were perhaps less explicitly recognized, jade being valued more for its use in exquisite ornaments and vessels, and for its links with antiquity. In the Ming and Qing periods ancient jade shapes and decorative patterns were often copied, thereby bringing the associations of the distant past to the Chinese peoples of later times.

Jade coiled dragon, c. 3500 B.C.E., Neolithic period, Hongshan culture, 4.6 x 7.6 cm, China (© 2003 Private Collection, © Trustees of the British Museum)

The subtle variety of colors and textures of this exotic stone can be seen, as well as the many different types of carving, ranging from long, smooth Neolithic blades to later plaques, ornaments, dragons, animal and human sculpture.

Neolithic jade: Hongshan culture

It was long believed that Chinese civilization began in the Yellow River valley, but we now know that there were many earlier cultures both to the north and south of this area. From about 3800–2700 B.C.E. a group of Neolithic peoples known now as the Hongshan culture lived in the far north-east, in what is today Liaoning province and Inner Mongolia. The Hongshan were a sophisticated society that built impressive ceremonial sites. Jade was obviously highly valued by the Hongshan; artifacts made of jade were sometimes the only items placed in tombs along with the body of the deceased.

Major types of jade of this period include discs with holes and hoof-shaped objects that may have been ornaments worn in the hair. This coiled dragon is an example of another important shape, today known as a “pig-dragon,” which may have been derived from the slit ring, or jue. Many jade artifacts that survive from this period were used as pendants and some seem to have been attached to clothing or to the body.

© Trustees of the British Museum