Found in large numbers in burials, these Chinese carvings constitutes an enormous effort by skilled craftsman.

Jade Cong, c. 2500 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China (The British Museum). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Neolithic China

Ancient China includes the Neolithic period (c. 7000–1700 B.C.E.), the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 B.C.E.), and the Zhou dynasty (1050–221 B.C.E.). Each age was distinct, but common to each period were grand burials for the elite from which a wealth of objects have been excavated.

The Neolithic Period, defined as the age before the use of metal, witnessed a transition from a nomadic existence to one of settled farming. People made different pottery and stone tools in their regional communities. Stone workers employed jade to make prestigious, beautifully polished versions of utilitarian stone tools, such as axes, and also to make implements with possible ceremonial or protective functions. The status of jade continues throughout Chinese history. Pottery also reached a high level with the introduction of the potter’s wheel.

Liangzhu culture

A group of Neolithic peoples grouped today as the Liangzhu culture lived in the Jiangsu province of China during the third millennium B.C.E. Their jades, ceramics, and stone tools were highly sophisticated.

Left: Bi, c. 2500 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China, jade and nephrite, 19.1 cm (The British Museum); right: Cong, c. 2500 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China, nephrite, 20.5 cm high (The British Museum)

Bi and cong

They used two distinct types of ritual jade objects: a disc, later known as a bi, and a tube, later known as a cong. The main types of cong have a square outer section around a circular inner part, and a circular hole, though jades of a bracelet shape also display some of the characteristics of cong. They clearly had great significance, but despite the many theories the meaning and purpose of bi and cong remain a mystery. They were buried in large numbers: one tomb alone had 25 bi and 33 cong. Spectacular examples have been found at all the major archaeological sites.

Cong, c. 2500 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China, nephrite, 20.5 cm high (The British Museum)

Cong

Cong, c. 3300–2200 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China, 49 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The principal decoration on cong of the Liangzhu period was the face pattern, which may refer to spirits or deities. On the square-sectioned pieces, like the examples here, the face pattern is placed across the corners, whereas on the bracelet form it appears in square panels. These faces are derived from a combination of a man-like figure and a mysterious beast.

Cong are among the most impressive yet most enigmatic of all ancient Chinese jade artifacts. Their function and meaning are completely unknown. Although they were made at many stages of the Neolithic and early historic period, the origin of the cong in the Neolithic cultures of south-east China has only been recognized in the last thirty years.

Cong were extremely difficult and time-consuming to produce. As jade cannot be split like other stones, it must be worked with a hard abrasive sand. This one is exceptionally long and may have been particularly important in its time.

Jade bi, c. 2500 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China (British Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Bi

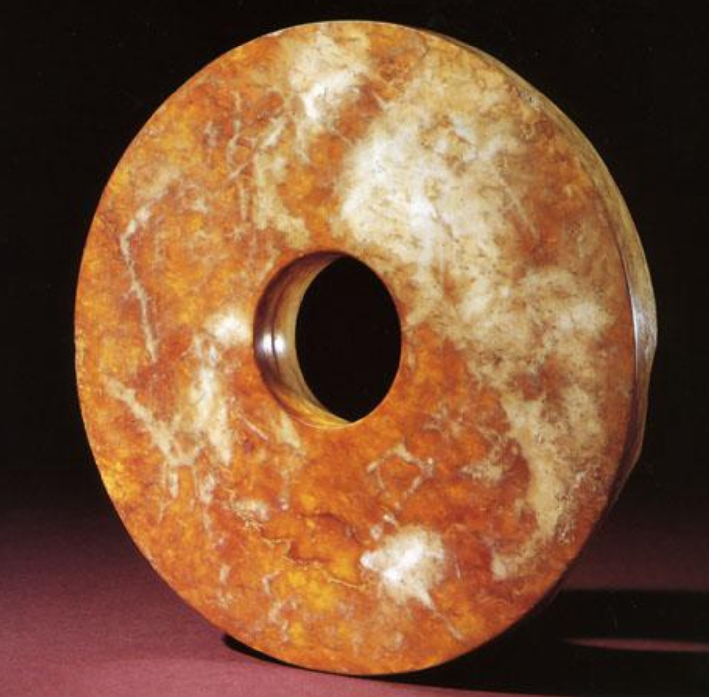

Jade disc, or bi, Liangzhu culture, 3300 B.C.E.–2200 B.C.E., 18 cm in diameter © Private Collection, © Trustees of the British Museum

Stone rings were being made by the peoples of eastern China as early as the fifth millennium B.C.E. Jade discs have been found carefully laid on the bodies of the dead in tombs of the Hongshan culture (about 3800–2700 B.C.E.), a practice which was continued by later Neolithic cultures. Large and heavy jade discs, such as this example, appear to have been an innovation of the Liangzhu culture (about 3000–2000 B.C.E.), although they are not found in all major Liangzhu tombs. The term bi is applied to wide discs with proportionately small central holes.

The most finely carved discs or bi of the best stone were placed in prominent positions, often near the stomach and the chest of the deceased. Other bi were aligned with the body. Where large numbers of discs are found, usually in small piles, they tend to be rather coarse, made of stone of inferior quality that has been worked in a cursory way.

We do not know what the true significance of these discs was, but they must have had an important ritual function as part of the burial. This is an exceptionally fine example, because the two faces are very highly polished.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources

Read more about death and material culture in ancient China in Reframing Art History.

Jade cong at Museum of the World.

J. Rawson, Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing (London: The British Museum Press, 1995, reprinted 2002).

J. Rawson (ed.), The British Museum book of Chinese Art (London: The British Museum Press, 1992).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”liangzhu,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] Where does history begin?

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:07] Well, history begins with writing, and that’s how we use the term prehistoric, “before writing.”

Dr. Zucker: [0:12] But of course, we’re not satisfied with only knowing literate cultures. We want to push back further and understand the cultures that are preliterate, but in order to invent writing you have to have a society, you have to have some stability, and we find that at the end of the Neolithic period.

Dr. Harris: [0:27] The Neolithic period begins around 10,000 B.C.E., when we have human beings who can settle down because they’ve figured out how to domesticate animals.

[0:37] They figured out how to farm, how to raise crops, and that brings some stability. They don’t have to live a hunter-gatherer existence anymore.

Dr. Zucker: [0:45] This is known as the Neolithic Revolution.

Dr. Harris: [0:48] And it really was a revolution. It completely changed human beings’ way of relating to nature. We could, for the first time, control nature to some degree.

Dr. Zucker: [0:57] This takes place after the end of the last ice age, and it may have to do with the environment becoming more hospitable, but we see this Neolithic Revolution in areas all over the world that were disassociated from each other.

Dr. Harris: [1:10] Sometime around 3000 [B.C.E.], many of those cultures also developed writing.

Dr. Zucker: [1:15] And writing is seen as one of the hallmarks of civilization. We see the development of what we recognize as civilization—that is, early cities, farming techniques, writing—developing in the great river valleys around the world. Most famously in Egypt, in Mesopotamia, in the Indus Valley, and in China.

Dr. Harris: [1:36] There are several areas in China that had sophisticated Neolithic culture. One in particular is called Liangzhu. This culture developed around what is today Shanghai and the Yangzi River.

Dr. Zucker: [1:48] Right at the delta of the Yangzi.

Dr. Harris: [1:50] Just like Egypt developed right around the delta of the Nile, and ancient Mesopotamia developed between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. It made sense, these were places where you could irrigate crops.

Dr. Zucker: [2:01] And in fact, the Liangzhu people seemed to have become expert rice growers and were able to create a surplus, which allowed them not to worry about eating, not to worry about feeding themselves. It allowed at least certain elements of society to begin to develop in more sophisticated ways.

Dr. Harris: [2:17] The Liangzhu culture was especially known for producing beautiful jade objects, specifically something that we call cong: square, hollow tubes that are decorated with lines and sometimes circles that represent faces.

[2:33] Some of them are short, and some of them seem to be stacks that are quite tall, and we’re looking actually at several examples here at the British Museum.

Dr. Zucker: [2:42] These were found in graves. Sometimes there were many cong in graves. There were also objects called bi. These are round disks, also with holes in the center. We have no idea what any of this means.

[2:54] This is a culture where we have found no traces of writing. It’s possible that they were preliterate or it’s possible that they wrote on a material that didn’t survive, but the result is all of the ideas that surround these objects are theories.

Dr. Harris: [3:07] Because they clearly represent faces, whether they’re monster faces or animal faces or human faces, this clearly meant something.

Dr. Zucker: [3:15] And there’s a great degree of regularity and specificity. Now, this jade is true jade or nephrite, and it is extremely hard. And this culture did not have tools that were harder than this nephrite. That is, they couldn’t carve it.

Dr. Harris: [3:29] You can’t incise into it. You can’t take a knife and cut into it. It’s just too hard.

Dr. Zucker: [3:33] You can’t even really scratch it. So when you look at these objects that are so precise, it’s almost impossible to imagine that they were produced by rubbing sand.

Dr. Harris: [3:43] Some of the lines are very, very fine and run parallel to each other. It’s important to think about the care with which these objects are made.

Dr. Zucker: [3:52] They are clearly symbols. There’s a uniformity, there’s an intentionality, there’s a clarity, and there’s tremendous effort. Though we don’t speak this language, we recognize it as the product of a human mind.

Dr. Harris: [4:05] A human mind that was trying to say something about power, perhaps, about our relationship to nature, about the spiritual world, about what happens after death. The kinds of questions that human beings ask all the time still. Their verticality, the repetition of these parallel lines, it’s hard not to think about these in relationship to issues of power.

Dr. Zucker: [4:29] Some scholars have suggested that the rectilinear quality of the cong is a symbol for Earth. That the round interior is a symbol of the heavens, of the sky, of the sun. These are symbols that develop later in China and it’s very seductive to link this Neolithic culture with later Bronze Age cultures.

Dr. Harris: [4:49] Well to read that definition back into time, it’s definitely tempting.

Dr. Zucker: [4:53] It is possible that this is the origin of those symbols, but we can’t really know.

[4:58] [music]