Banshan type jar, Gansu ware, Neolithic period, 5000–2000 B.C.E., earthenware with iron pigments, China, 36.1 x 42.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1930.96)

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is characterized by the beginning of a settled human lifestyle. People learned to cultivate plants and domesticate animals for food, rather than rely solely on hunting and gathering. That coincided with the use of more sophisticated stone tools, which were useful for farming and animal herding. In China, this period began around 7000 B.C.E. and lasted until 1700 B.C.E.

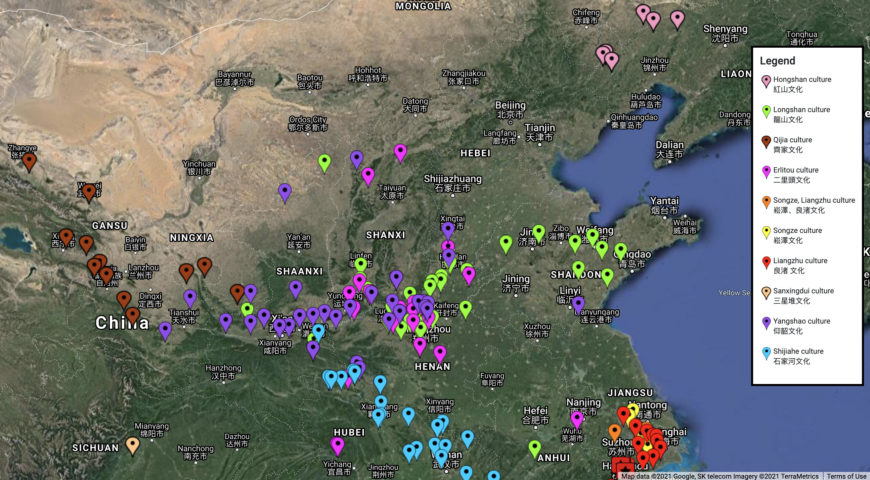

Map of Neolithic China, with hotspots corresponding to published excavations. Different hotspot colors represent the different cultures revealed. See a responsive map here (underlying map © Google)

It is traditionally believed that Chinese civilization first emerged along the Yellow River and then spread to other parts of China. However, recent archaeological evidence suggests that a number of distinct cultures developed simultaneously across China, all along waterways. These cultures were located near the coastal areas, the Yellow River in the north, and the Yangzi River in the south. They are usually named after the site where remains of the culture were first discovered by modern archaeologists.

Neolithic people did not write. However, because they lived in settled communities, they left many traces behind, including the foundations of their houses, burial sites, tools, and crafts. We learn from the archaeological record that their diet included millet or rice, they domesticated pigs and dogs, and, as in all Neolithic cultures, there was extensive pottery production. Cultures in central China along the Yellow River were known for their painted pottery. Toward the late Neolithic period (c. 5000–1700 B.C.E.), fine gray and black pottery of elaborate forms were produced by cultures along the east and southeast coasts. The forms and decorative patterns of these pottery vessels continued to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 B.C.E.) and inspired the craftsmen of bronzes.

Hongshan culture, pendant in form of a mask, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E. (late Neolithic period), jade (nephrite), 5.7 x 17.2 x .4 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Therese and Erwin Harris, F1991.52)

Jade carving is another advanced craft invented by Neolithic people. It plays a major part in Chinese culture to this day. Neolithic jade objects include personal ornaments, such as bracelets, earrings, and pendants, but most importantly, objects designed for ritual or ceremonial use, such as axe heads, blades, and knives. Hongshan culture (c. 3800–2700 B.C.E.) in the northeast produced some of the earliest jades used as pendants, including the so-called pig dragons (a creature with the head of a pig and the curled body of a dragon) and the toothed pendants (such as the the pendant in the form of a mask, discussed in more detail below). [1] Both kinds were found placed on the chest of tomb occupants.

Liangzhu culture 良渚 (c. 3300–ca. 2250 B.C.E.), One-tier tube (cong 琮) with masks, Late Neolithic period, c. 3300–c. 2250 B.C.E., jade (nephrite), China, Lake Tai region, 4.5 x 7.2 x 7.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1916.118)

Liangzhu (c. 3300–2250 B.C.E.) people along the southeast coast made jade objects shaped like disks (bi, prounced as ‘bee’) and tubes (cong, pronounced as ‘tsong’) in large numbers. These objects were found carefully lined up around the deceased. Although the exact function of these jade pieces remains a mystery, they no doubt possessed important social and ritual value.

Sanxingdui culture, tube (cong), c. 2000–1000 B.C.E. (late Neolithic period), serpentine, China, Sichuan province, 3.4 x 6.4 cm (Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: The Dr. Paul Singer Collection of Chinese Art of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; a joint gift of the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, Paul Singer, the AMS Foundation for the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities, and the Children of Arthur M. Sackler, S2012.9.163)

Status objects like elaborate pottery and carved jades were placed in tombs during the Neolithic period. This practice suggests two things: Neolithic people’s belief in the afterlife and the emergence of social classes. Only important and wealthy individuals had the privilege of being buried with these precious objects, especially jades. These objects were luxuries, not necessary for life but cherished for for their beauty and ceremonial value. They required large amounts of raw materials and skilled labor to produce and were therefore accessible only to the ruling class, thus showing the existence of a surplus of wealth and labor in society.

The arts of Neolithic China not only demonstrate technical sophistication and superb craftsmanship but also reveal social organization and the emergence of religious beliefs.

Hongshan culture, pendant in form of a mask, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E. (late Neolithic period), jade (nephrite), 5.7 x 17.2 x .4 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Therese and Erwin Harris, F1991.52)

Pendant in the form of a mask

Hongshan culture, detail of pendant in form of a mask, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E. (late Neolithic period), jade (nephrite), 5.7 x 17.2 x .4 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Therese and Erwin Harris, F1991.52)

A single hole sits between the eyes. It is neatly drilled from both sides of the plaque. Can you guess why it’s there? It would have allowed the jade piece to be worn similar to a modern pendant, suspended on a cord and worn around the neck. It would have felt cool against the skin. All details are worked from the front, and the back is flat and polished smooth.

Amulet in the Form of a Seated Figure with Bovine Head 牛首玉人, c. 4700–2920 B.C.E. (Neolithic period), probably Hongshan culture, jade (nephrite), northeast China, 13.2 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

The motif and meaning of toothed pendants have not yet been deciphered. Many scholars suspect that they are similar to other jade pendants that depict fantastic creatures. For example, an object from the Cleveland Museum of Art depicts the head of a cow on a human-like body and is also pierced for wearing as a pendant. These pendants appear to be more than mere decorations. They were all excavated from burial sites and found on prominent locations of the body. This pendant was most likely a power and status symbol for an elite member of the Hongshan community.

For the classroom

- What is a pendant? How does a pendant compare to other types of jewelry?

- What do you think the significance of the face is? What could this represent?

- Who do you think wore this? When and for what types of occasions do you think it was worn? What about the piece leads you to think that?

Additional resources:

This essay on the National Museum of Asian Art’s website

Read more about the Hongshan pendant from Jades for Life and Death

Read more about the Liangzhu cong tube from Jades for Life and Death

Shuping Deng. Neolithic jades in the collection of the National Palace Museum. no. 114 Tabei Shi, September 1992. p. 5, fig. 2.

The Harris Collection: Important Early Chinese Art. New York, March 2017. p. 8, fig. 1.

Shuping Deng. You ‘jia’ dao ‘zhen’ de jianxin manchanglu: Yi Hongshan yuqi weili. No. 217 Taipei, 2001. p. 17, fig. 15.

Elizabeth Childs-Johnson, Fang Gu. Yuqi shidai: Meiguo bowuguan cang Zhongguo zaoqi yuqi [The Jade Age: Early Chinese Jades in American Museums]. Beijing, 2009. pp. 24-25.

Dashun Guo. Hongshan wenhua gouyunxing yupei yanjiu: Liaohe wenming xunli zhisi. No. 164 Taipei, 1996. p. 48, fig. 13.

Elizabeth Childs-Johnson. Jades of the Hongshan Culture: The Dragon and Fertility Cult Worship. tome XLVI, 1991. p. 85, fig. 4.

Meili Yang. Juanyunshan (Jiaoji) Cuishi Shuilinlin: Xinshiqi Shidai Beifangxi Huanxing Yuqi Xilie zhi yi: Gouyun Xingqi. No. 126 Taipei, 1993. p. 86, fig. 11.

Jenny F. So. A Hongshan Jade Pendant in the Freer Gallery of Art. Hong Kong, May 1993. pp. 87-92.

Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture., July 2009. p. 196, fig. 19c.

Andrew Lawler. Beyond the Yellow River: How China Became China. vol. 325 no.5943 Washington, August 21, 2009. p. 935.