Murals in two Liao Dynasty tombs: Representations of exquisite objects and human servants in Liao dynasty tombs are abundant.

Read Now >Chapter 29

Art in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period and Song dynasty China

Though it was once unified under the great Tang empire (which came to an end in 907), medieval China (literally “the Central Kingdom,” or Zhongguo 中國) initially disintegrated into several contemporaneous kingdoms with shifting boundaries and cultures. Textbooks typically gloss over this splintered, war-torn period, known somewhat confusingly as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period. Instead, they focus on the reunification under the Song dynasty in 960, when Chinese society emerged with some of the most advanced technological and artistic innovations in the world—despite having lost much of the territory of the Tang empire.

Bowl, Northern Song or Southern Song dynasty, 12th century, Jian ware, Stoneware with iron-pigmented glaze, China, Fujian province, 8.8 x 19.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1909.369)

The visual arts reveal how moments of chaos and peace both shaped China’s long history of dynasties ruled by emperors (known as the imperial era, spanning 221 B.C.E. to 1912) and gave rise to one of the most remarkable chapters in the history of Chinese art. Paintings, sculpture, architecture, and ceramics expose this moment of upheaval (during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period) and eventual reunification (during the Song Dynasty), demonstrating an extraordinary quest for harmony in society and peace for the nation.

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period

If China’s earlier Tang dynasty was a golden age of arts and culture, then the tenth century began as a stark contrast—frequent incursions by tribes from the north and warlord-controlled kingdoms divided China into Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960).

Map of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

One of these dynasties, the Liao dynasty (907–1125), expanded their territory to the north and claimed lands formerly possessed by the Tang empire. This dynasty was ethnic-Khitan (distinct from the Han Chinese). The Liao maintained relations with the Korean peninsula (one important point of cultural exchange) while seeking to emulate their predecessors, the Tang dynasty.

Liao Dynasty Tombs, Liao Dynasty, 907–1125 (大遼), at Dongfengli Neighborhood, Datong City, China, Shanxi Province 辽 山西大同东风里

The Buddhist sculptures, murals, and architecture of the Liao empire reveal widespread cultural contacts that flourished along the Silk Roads. The Liao, and later the Jurchens and the Mongols, remained an ever-present threat to the south, where several dynasties and kingdoms jockeyed to reunify the empire.

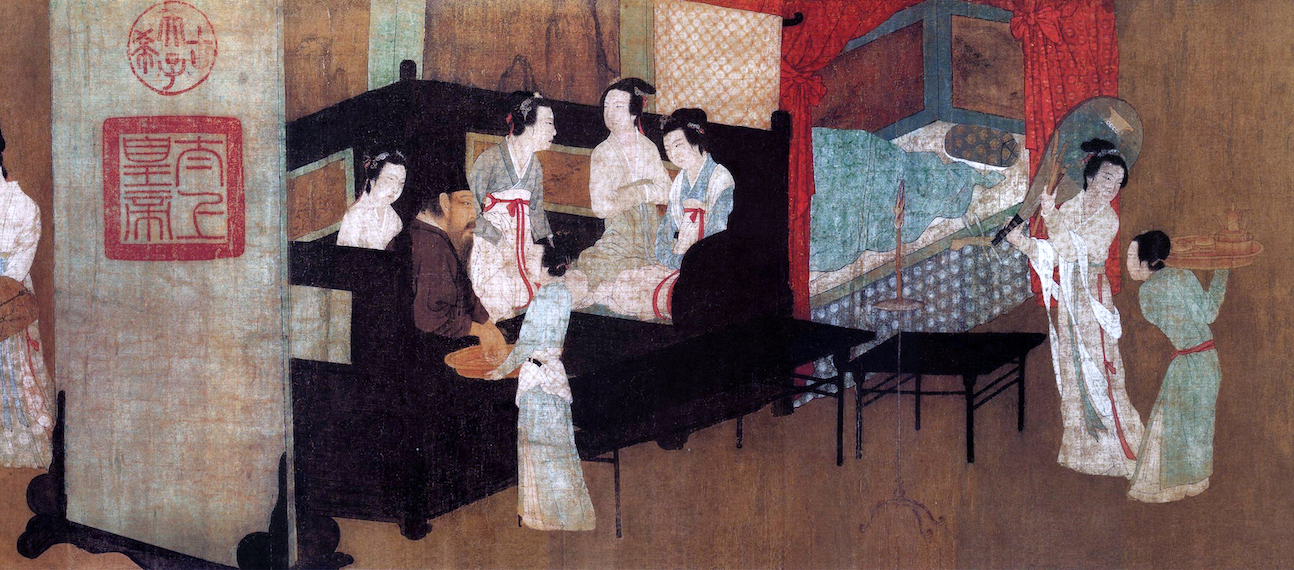

Gu Hongzhong, detail of Han on a couch with guests (left) and a rumpled bed (right), The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

Other artists of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms took an interest in matters of morality and integrity, which were viewed as essential for good governance in Confucian thought. Paintings often probed the boundaries of official decorum and social relations by picturing loyal subjects, virtuous officials, charming courtesans, and wayward ministers (such as in Gu Hongzhong’s Night Revels)—archetypes that may have served as an admonition to correct undesirable conduct, or to characterize a harmonious society under the benevolent rule of the emperor.

Read more about tombs, painting, and sculpture of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period

Arhat (Luohan): This Buddhist Monk statue defies traditional depictions of religious figures.

Read Now >

Gu Hongzhong, The Night Revels of Han Xizai: This handscroll offers an intriguing portrayal of a court minister testing the bounds of Confucian propriety during the Five Dynasties.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The Song Dynasty

It was not until the Song dynasty (960–1279) that power once again coalesced into a single empire, first in the north (the Northern Song dynasty, 960–1127) and then in the south (the Southern Song dynasty, 1127–1279).

The Song dynasty at its greatest extent in 1111 (map: Kanguole, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Although the Song dynasty lacked the vast territory of the Tang dynasty, both art and commerce flourished with the support of the Song court. One Song emperor established an Imperial Painting Academy, recruiting artists from around the empire to fulfill imperial commissions and collecting historic works. In addition, court officials meticulously documented each painting in the imperial collection, thereby creating a framework for the study of Chinese paintings that scholars still consult today. When the court relocated from the northern city of Bianjing (now Kaifeng) to the southeastern city of Hangzhou due to the advance of the Jurchens, artists continued to explore the relationship between man and nature in both pictures and poetry.

Urban Life and Society in the Song Dynasty

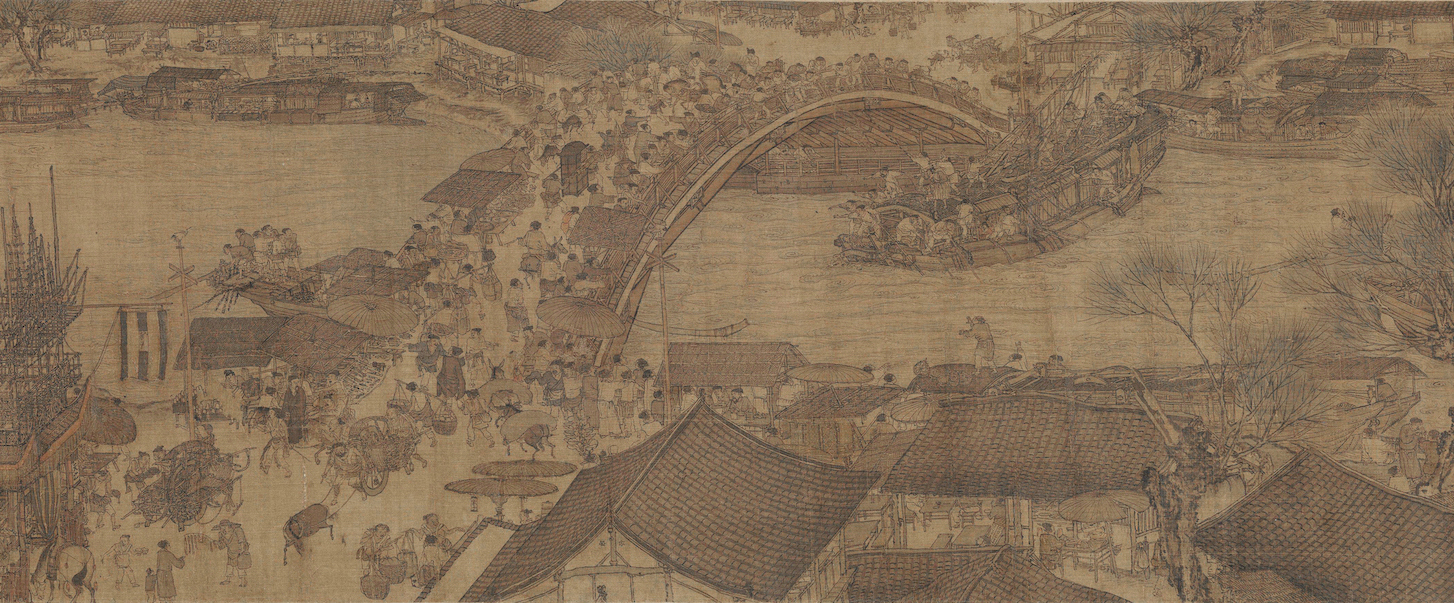

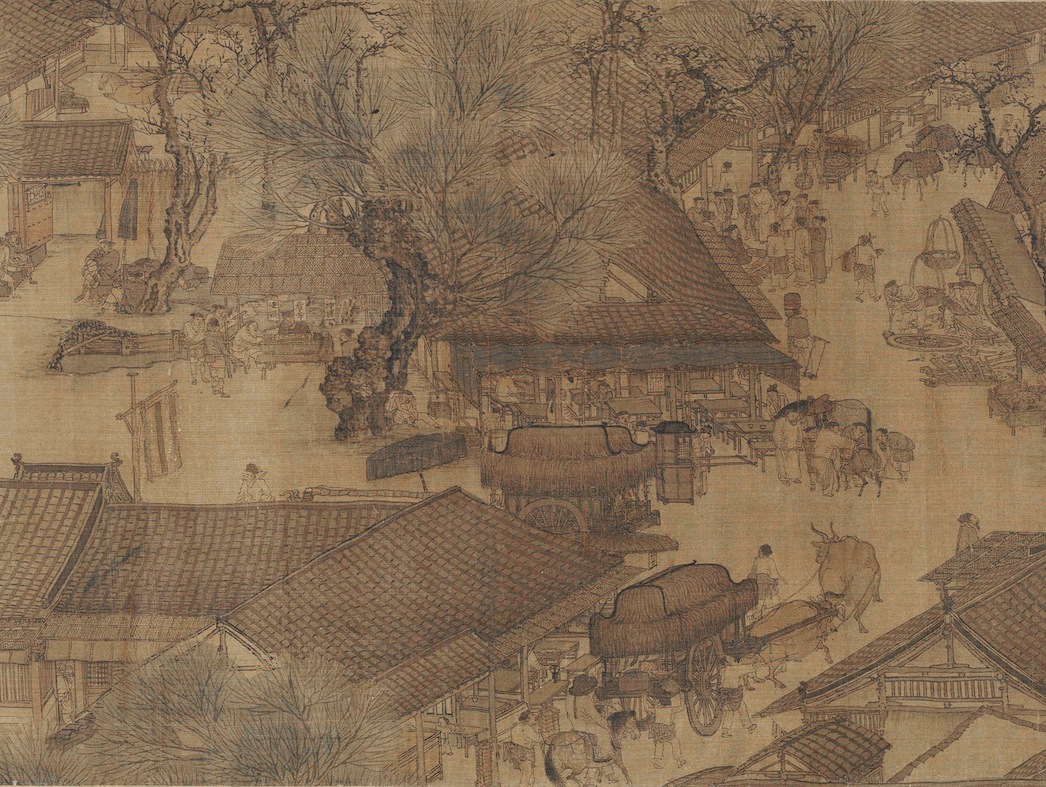

Attributed to Zhang Zeduan, Rainbow Bridge (detail), Along the River during Qingming Festival, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 11th–12th century, 24.8 x 528.7 cm (Palace Museum, Beijing)

Reunification under the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) ushered in paintings that present urban life and commerce in vibrant detail. Artists took a close look at all subjects, from the minute to the grand, from the built to the natural world. A technique called ruled-line painting (jièhùa 界畫, or drawing aided with line-brush, ruler, and compass) grew popular in the Northern Song as a mode for depicting architecture with incredible precision, using measurements and rules that were applied to palaces, gardens, and other man-made objects such as boats and chariots. By precisely rendering the architecture of daily life, artists conveyed a sense of truth—a vision that suggested the prosperity that comes with peace—a welcoming sight after several decades of turmoil during the Five Dynasties period.

Read about Northern Song depictions of urban life

Attributed to Zhang Zeduan, Along the River during Qingming Festival: This handscroll offers a rare glimpse of the thriving commercial activity of medieval China.

Read Now >/1 Completed

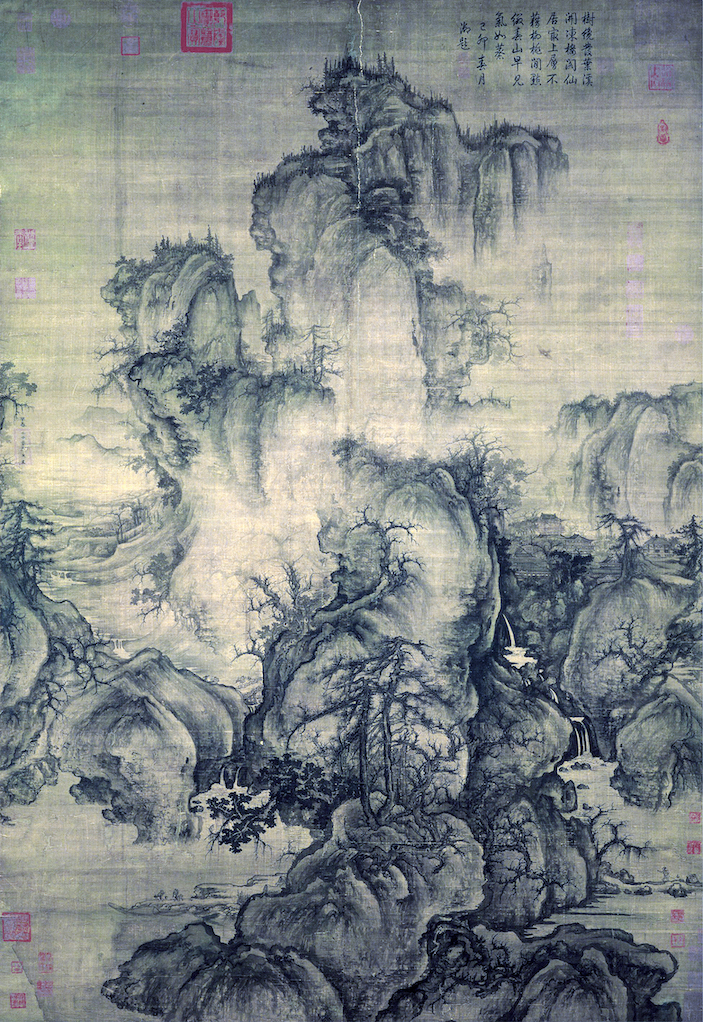

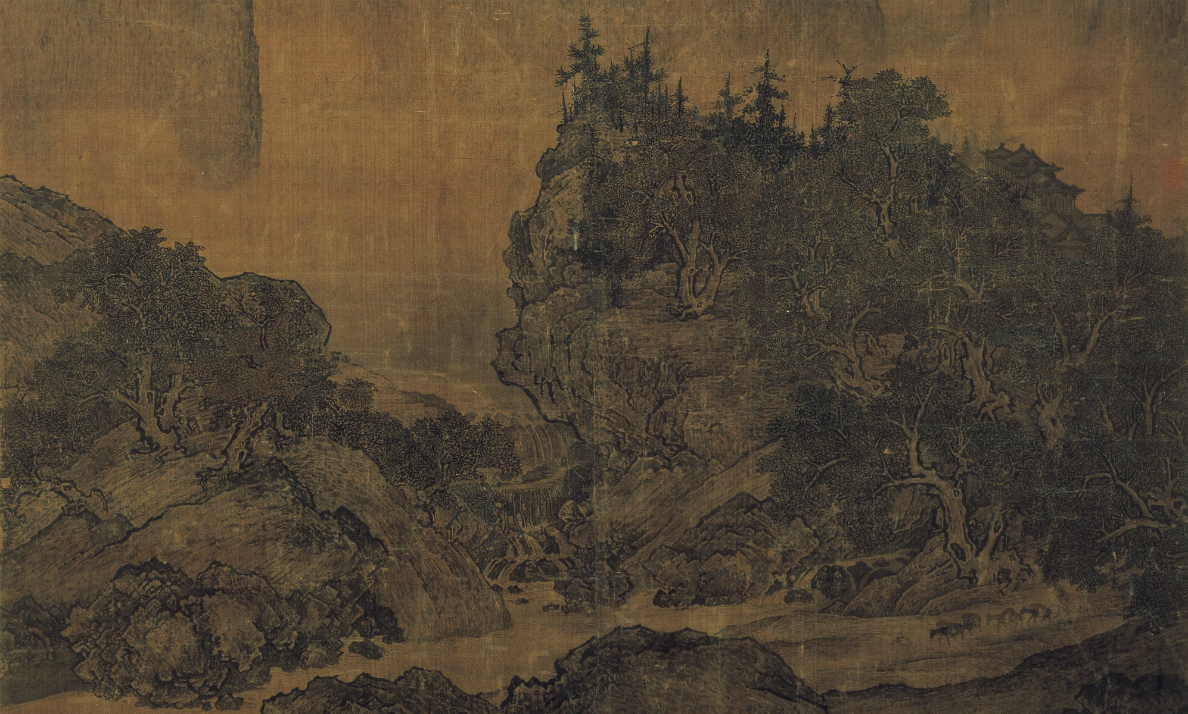

Monumental Landscape Painting

Guo Xi, Early Spring, signed and dated 1072, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk 158.3 x 108.1 (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Perhaps most iconic of the paintings from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period through the Northern Song dynasty are the grand views of nature known as “monumental landscape paintings,” which coalesce as a genre at this time and explore the balance between nature and humanity. Whether the rugged, mountainous topography of the north or the low-lying waterways of the south, monumental landscape paintings capture the essence of nature in lavish detail.

Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains, ink on silk hanging scroll, c. 1000, 206.3 x 103.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Each work is like a journey of the senses, as one’s eye travels over dusty trails, past misty waterfalls to cliffside temples. Artists found little need for color, instead relying on their handling of the brush and ink by using contour lines for modeling, brushwork variations for texture, and ink washes for atmospheric effects, all on the unforgiving medium of silk (the slightest touch of ink and water will set permanently on this highly absorbent, protein-based fabric). Few figures appear in the landscapes, which exude a sense of vitality and otherworldliness—humanity as one small part of the living, breathing entity of nature.

Images of nature in harmony could represent a metaphor for peace and unity among people. In “A Note on the Art of the Brush,” the Five Dynasties painter and theorist Jing Hao (c. 855–915), described landscape paintings in terms of both Daoist and Neo-Confucian principles, explaining how visions of nature could give form to ideal qualities in state and society. Typically mounted as hanging scrolls, patrons displayed these large-scale works on walls of mansions or palaces to communicate a vision of harmony between man and nature, or the emperor and his subjects.

Read about monumental landscape painting

Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains: This monumental landscape is the most majestic example of early Song “mountain water” painting.

Read Now >/1 Completed

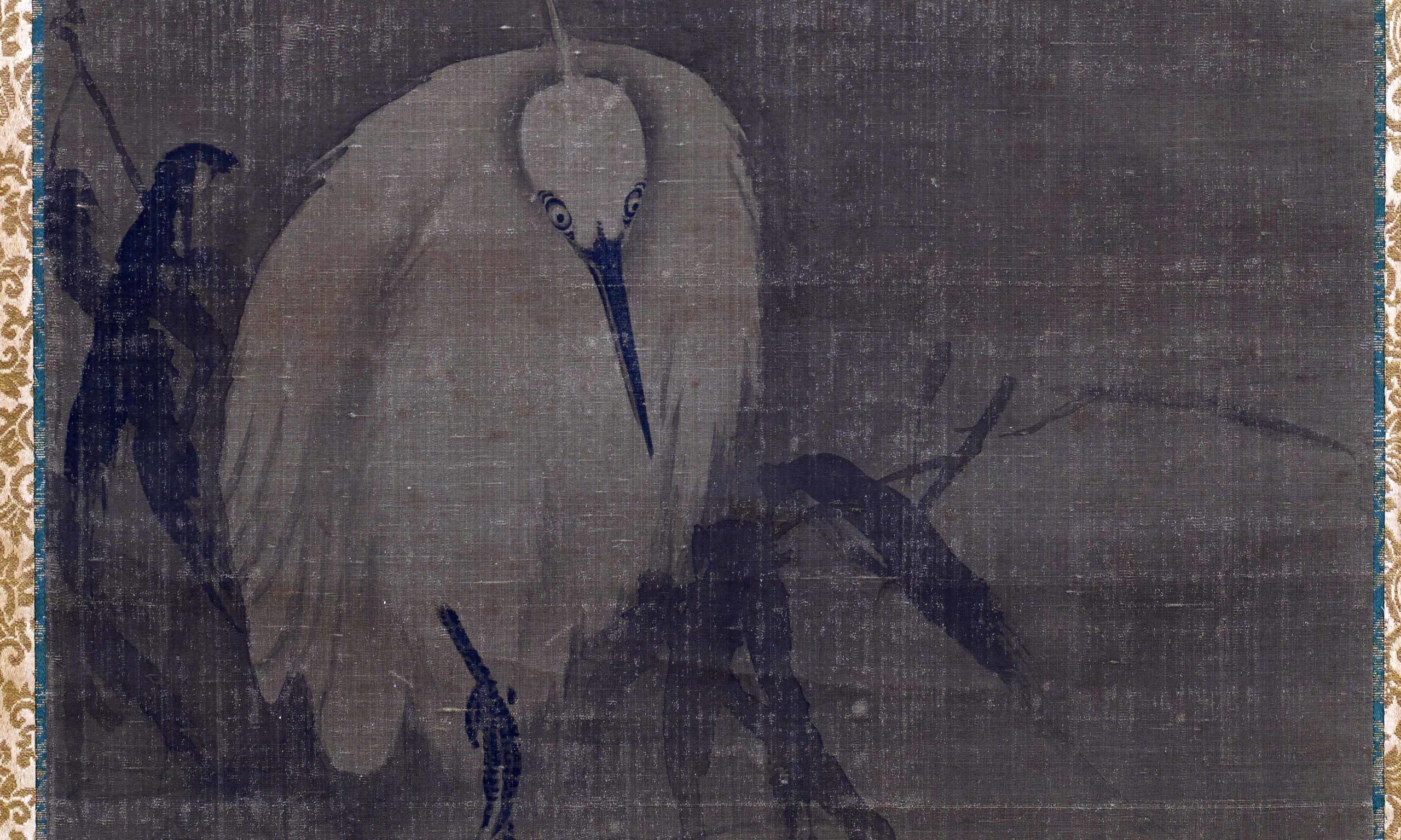

Poetic Imagery

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 1112.51 x 138.2 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang)

The notion of the “Three Perfections,” or the harmony of painting, poetry, and calligraphy emerged during the Song dynasty. Calligraphy, through its attention to brush and line, was the backbone of painting, which was inspired by poetry. All three separate forms could be present in a painting, whether literally or metaphorically. In other words, the words of a poem could shed light on the possible meanings and nuances of the picture, and vice versa. Often painted on the small format of the album leaf, pictures would usually accompany a poem either directly on the painting or facing it. When preparing a painting to offer as a gift for a retirement or marriage, for example, court artists might select an image such as a bird or flower that could serve as a symbol of dignity or love. A poem would further activate the meaning of the message, thereby serving as a good omen or wish for the recipient.

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 1112.51 x 138.2 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang)

Academy artists also drew on the relationship between words and pictures to convey auspicious meanings (signs of good fortune). They drew on the aesthetic principles of Northern Song Emperor Huizong, who emphasized close observation and accurate portrayal of the subject. Just as a spring landscape could act as a metaphor for harmony and peace in the land, auspicious omens also could be found in natural subjects and events, such as a multi-headed grain stalk or a flock of cranes descending over the capital that could be a metaphor for good governance. With great attention to the subjects’ form, court artists employed calligraphy, poetry, and painting to record such remarkable acts of nature that could also assert the “Mandate of Heaven,” or tīanmìng 天命, the emperor’s heavenly right to rule.

Read about poetic imagery

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes: This handscroll records natural phenomena that would be interpreted as a good omen for the dynasty.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Buddhist Patronage

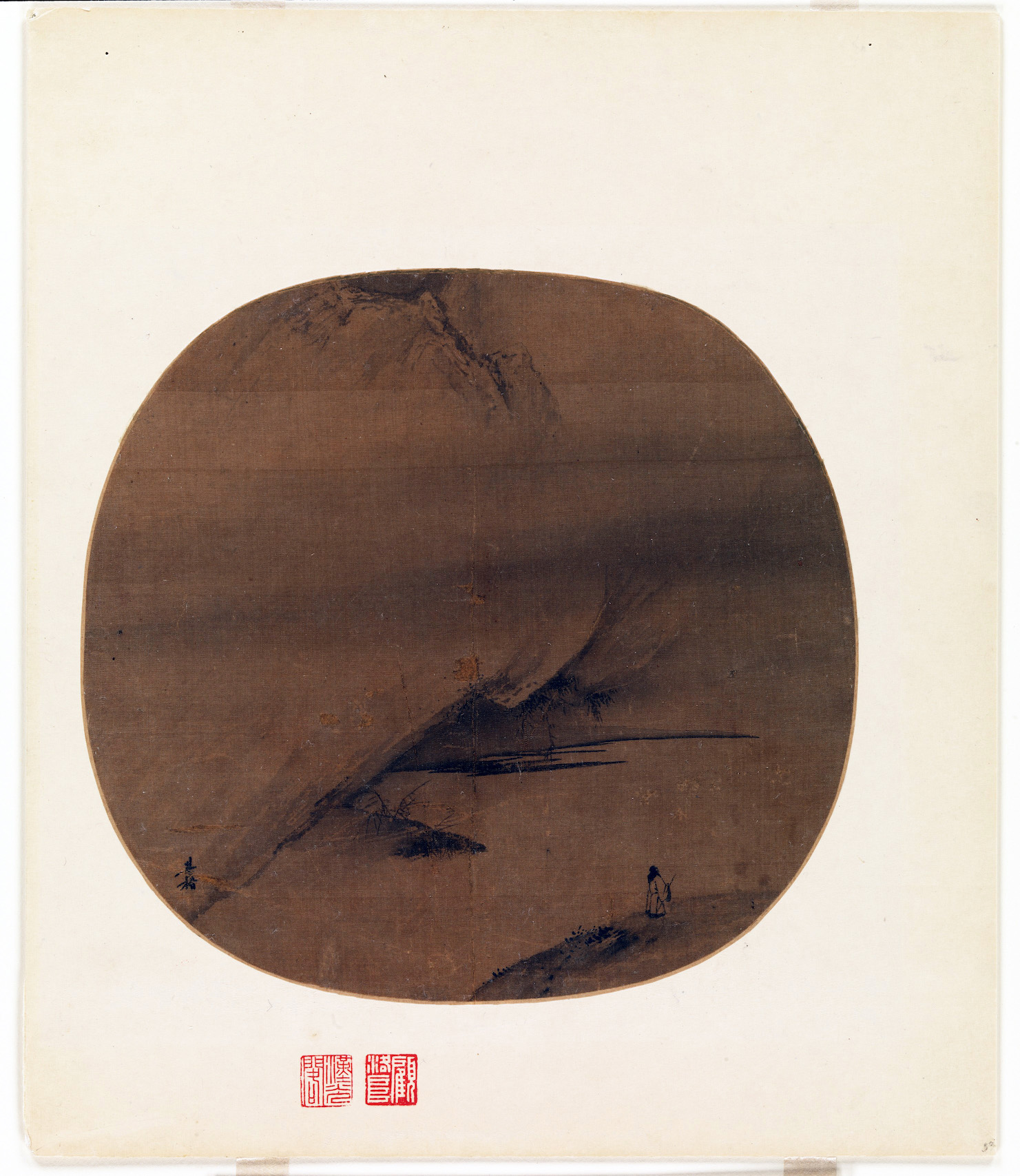

Court artists of the Southern Song dynasty further developed evocative images with attention to Chan Buddhism. The Chan aesthetic, referred to as Zen in Japan and Son in Korea, favors a spontaneous approach that reflects the suddenness of enlightenment sought by Chan devotees—unlike the study of Buddhist scriptures and devotional practices. The values of unadorned simplicity, artlessness, and purity characterize Chan-inspired artworks throughout East Asia; works that share a feeling for unforced naturalness and deep respect for nature. Hangzhou, the site of several important Chan monasteries, became a center for the transmission of Chan throughout the region, in particular to Japan.

Liang Kai, Poet strolling by a marshy bank, early 13th century, Southern Song dynasty, fan mounted as an album leaf; ink on silk, 22.9 x 24.3 cm, China (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Southern Song artists were not only inspired by Chan Buddhism, but also by lyrical poetry that follows a particular meter intended to be sung aloud. Paintings often display the neat fitting of elements into small spaces, like architecture or rocks, to suggest a coherence of space in an asymmetrical composition. Such arrangement of forms into a “one-corner composition” suited smaller pictorial formats, such as the album leaf or fan, and lent space for a poem or poetic couplet to be added by a skilled calligrapher or even the emperor or empress.

Detail of reclining Buddha, Parinirvana (the death of Shakyamuni attended by bodhisattvas), Mt. Baoding, Dazu. Southern Song Dynasty. 102′ long (photo: Mulligan Stu, CC BY 2.0)

The Southern Song Emperor Xiaozong famously wrote that one should apply “Buddhism to cultivate one’s mind, Daoism to nurture one’s body, and Confucianism to govern the world.” As the arts of this era reveal, Buddhism did not exist in isolation; Daoism and Neo-Confucianism complemented the arts of Buddhism by further affirming the court’s message of cultural unity. Moreover, different Buddhist sects each offered unique visual approaches to enlightenment as seen in temple architecture, sculpture, and painting. Patrons varied widely, too, with both court and lay patronage establishing rich repositories of Buddhist architecture, sculpture, devotional painting, and material culture throughout the empire.

Read essays and watch videos about Buddhist patronage

Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape: A Japanese Zen painting helps to understand Chan Buddhism in China.

Read Now >

Mt. Baoding, Dazu rock carvings: The monumental sculptural complex at Mt. Baoding consists of nearly 10,000 painted and gilded images of Buddhist deities and narrative scenes carved out of sandstone.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Ceramic Production

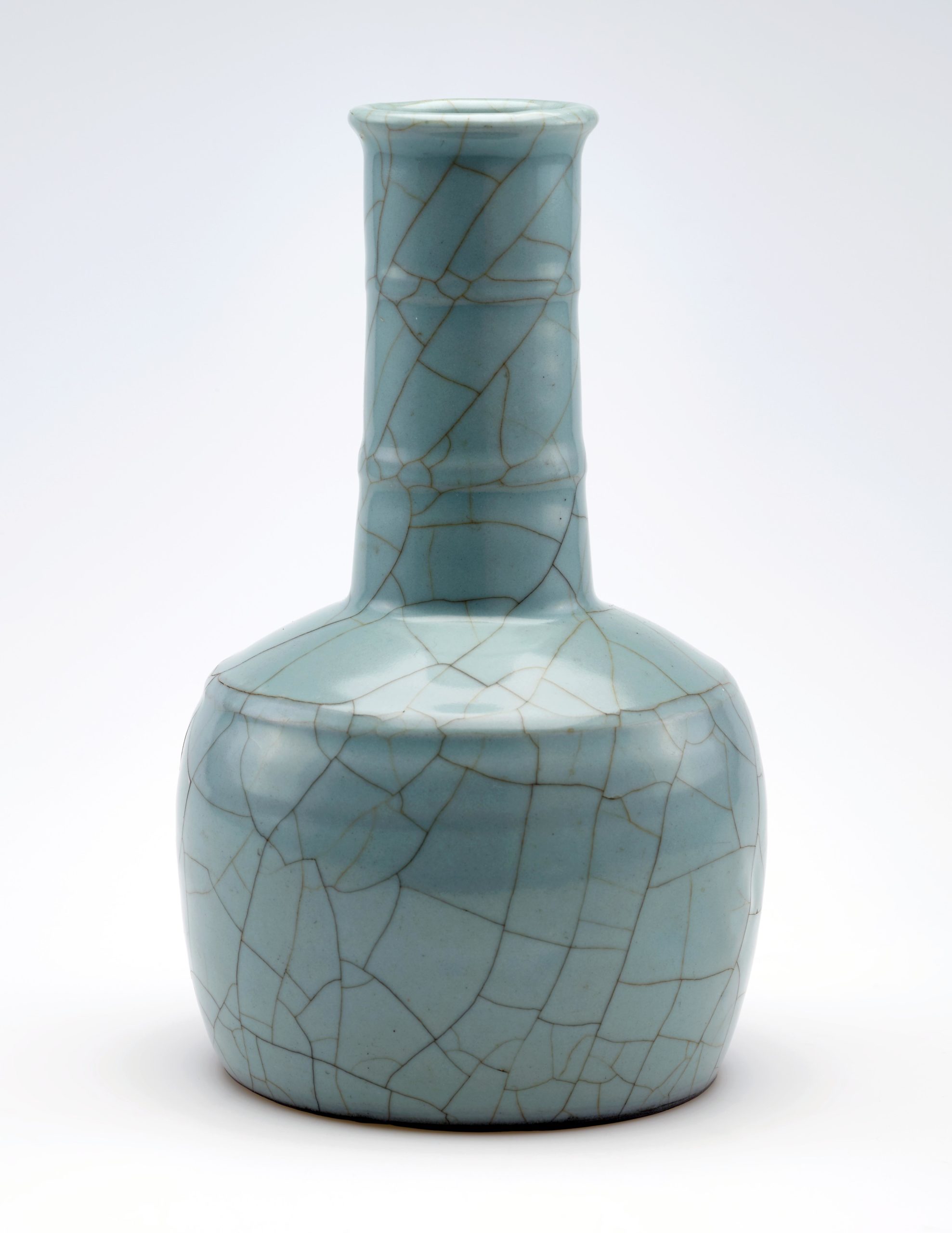

Guan ware long-necked vase with raised bow-string decoration, Southern Song dynasty, 12th century, Guan ware, stoneware with Guan glaze, China, Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, Jiaotanxia kiln, 23.2 x 14.1 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1911.338)

The Song dynasties amassed the resources and organization for a thriving ceramics production, both for domestic consumption and export abroad. Song wares are known for the variety of their shapes, glazes, and decorative programs. Examples range from the elaborate, incised motifs seen on the ivory-hued wares of the Northern Song dynasty, to thick applications of crackled, green-blue glazes on the celadons of Southern Song official ware, or gūanyáo 官窯, that resembled the color of jade or tender spring plants.

Pillow, Northern Song dynasty, 1063, Cizhou-type ware, stoneware with white slip under transparent colorless glaze, China, probably southern Shaanxi province, 19.2 x 39.8 x 10 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer, F1974.2)

The social uses of each ware differed widely, as well. While the Southern Song court oversaw the production of official wares at the imperial kilns near the capital, common or popular wares, such as Jian ware, circulated broadly. Some served as imperial tribute, while others functioned as tea wares in Buddhist monasteries. Tea drinking became an important social activity as well as religious practice, and it served as an important bridge between monks and laypeople.

As a portable art form, ceramics also traveled as gifts between cultures. A Chinese envoy to Korea, Xu Jing, who visited the capital in Gaeseong in 1123, noted the resemblance between ceramics from Korea and Song celadons. He saw a conscious emulation of certain stylistic features of Chinese wares, such as the shapes of vessels and standard decorative motifs. In the decades that followed, Korea produced its own celadons so remarkable that they were offered in tribute to the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)—a compelling example of how cross-cultural exchange within Asia generated further innovation and circulation.

Essays and videos about ceramic production

Ceramic pillows: They became a popular domestic item among middle- and upper-class families during the Song dynasty.

Read Now >

Long-necked vase: Guan ware is probably one of the rarest and most admired types of Chinese ceramics in the present world.

Read Now >

Bowl with “oil spot” glaze: Jian ware tea bowls were highly prized in China but seem to have gone out of fashion there, whereas the Japanese adopted them for use in tea ceremonies.

Read Now >

Celadons of the Goryeo Dynasty: Korean potters adapted and refined celadon technology from China to create distinctively Korean ceramics revered by elites in Korea, China, and Japan alike.

Read Now >/5 Completed

If the arts of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms offered reflections on nature and morality that spoke to the political upheaval of the period, then artists of the Song dynasty deepened themes of peace and unity through extraordinary innovations in the visual arts. Through awe-inspiring landscapes, intimate views of urban life, sacred sculptures, and radiant ceramics, artists re-envisioned cultural harmony for a new era.

Key questions to guide your reading

What is meant by the “three perfections?”

Where do we see the aesthetic of Chan Buddhism in East Asian art?

How did Song dynasty ceramics circulate in Chinese society and throughout Asia?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat is meant by the “three perfections?”

Where do we see the aesthetic of Chan Buddhism in East Asian art?

How did Song dynasty ceramics circulate in Chinese society and throughout Asia?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

ruled-line painting

monumental landscape painting

ink or color wash

three perfections

Mandate of Heaven

one-corner composition

three teachings

celadon

Confucianism

Daoism

Learn more

“Song Engagement with the Outside World,” The Song Dynasty in China, Asia for Educators, Columbia University