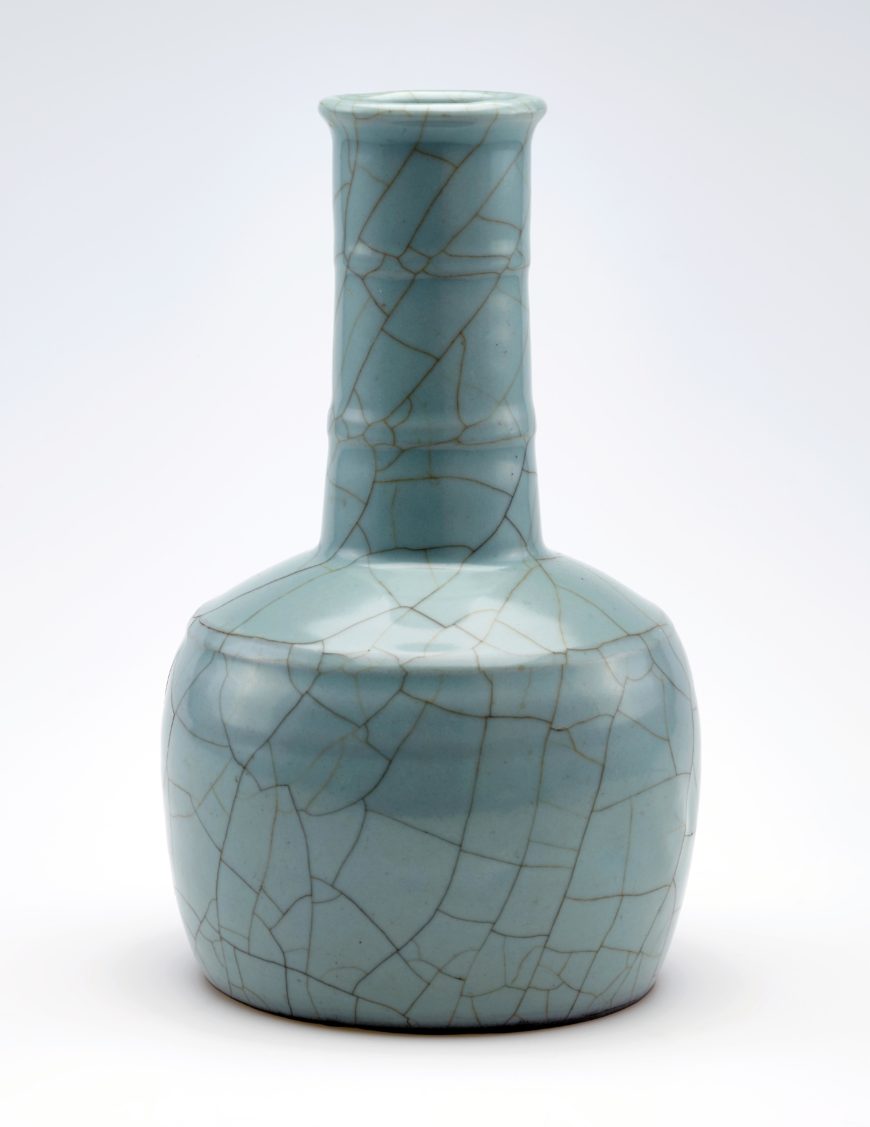

Guan ware long-necked vase with raised bow-string decoration, Southern Song dynasty, 12th century, Guan ware, stoneware with Guan glaze, China, Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, Jiaotanxia kiln, 23.2 x 14.1 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1911.338)

This is a beautifully shaped ceramic vase. It has a squat body, angled shoulders, and an elegant long neck. The neck is decorated with two raised “bow string” lines. A soft grayish-blue glaze covers the vase. Its size and glaze make the vase not only a pleasure to look at, but ideal to be held in one’s hand to appreciate. Patterns of crackle lines form in the glaze, allowing the dark, clay body to peak through. The crackles are not entirely accidental cracks—a defect that would sometimes occur from a failed firing of ceramics—instead, the potters intentionally created this effect for its visual appeal.

Detail of Guan ware long-necked vase with raised bow-string decoration, Southern Song dynasty, 12th century, Guan ware, stoneware with Guan glaze, China, Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, Jiaotanxia kiln, 23.2 x 14.1 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1911.338)

Through years of ceramic-making practice, Song potters learned that when the clay body and glaze contract at different rates after the firing, the tension caused would generate the crackles. When making ceramic objects like this vase, Song potters would apply multiple layers of glaze and fire frequently at a moderate temperature before a final high-temperature firing. By controlling the last phase of cooling, potters encouraged the glaze to shrink more than the body and crackle. Thus, Song potters exploited what might appear to be a technical defect for its aesthetic effect.

This vase is a typical Southern Song “Guan” ware, literally “official” ware. When the capital of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) was relocated from northern China to modern day Hangzhou, Guan ware kilns were established nearby and produced stonewares mostly for the imperial court. Guan ware is probably one of the rarest and most admired types of Chinese ceramics in the present world. They all have common features. The body is very thin, often thinner than the glaze. The thick glaze is typically applied in many coats, and brownish or blackish crackles spread throughout it.

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

For the classroom

Discussion questions:

- The founder of the National Museum of Asian Art, Charles Lang Freer, travelled across Asia more than 100 years ago to collect artworks. He selected this vase because he thought it was especially beautiful. What qualities of the vase do you think convinced Freer to purchase it and bring it back to the United States? Would you purchase this object if you were an art collector? Why or why not?

- Research three types of Chinese ceramics: Guan ware, Ru ware, and Celadon (also called Greenware). Why do you think the blue-green color of these styles was especially valued in China?

- Search the Freer and Sackler collections page or the internet for images of Guan ware, Ru ware, Celadon, or other types of ceramics. Record the most interesting shapes and colors that you find in a sketchbook or in an online collection using Smithsonian Learning Lab or Pinterest.