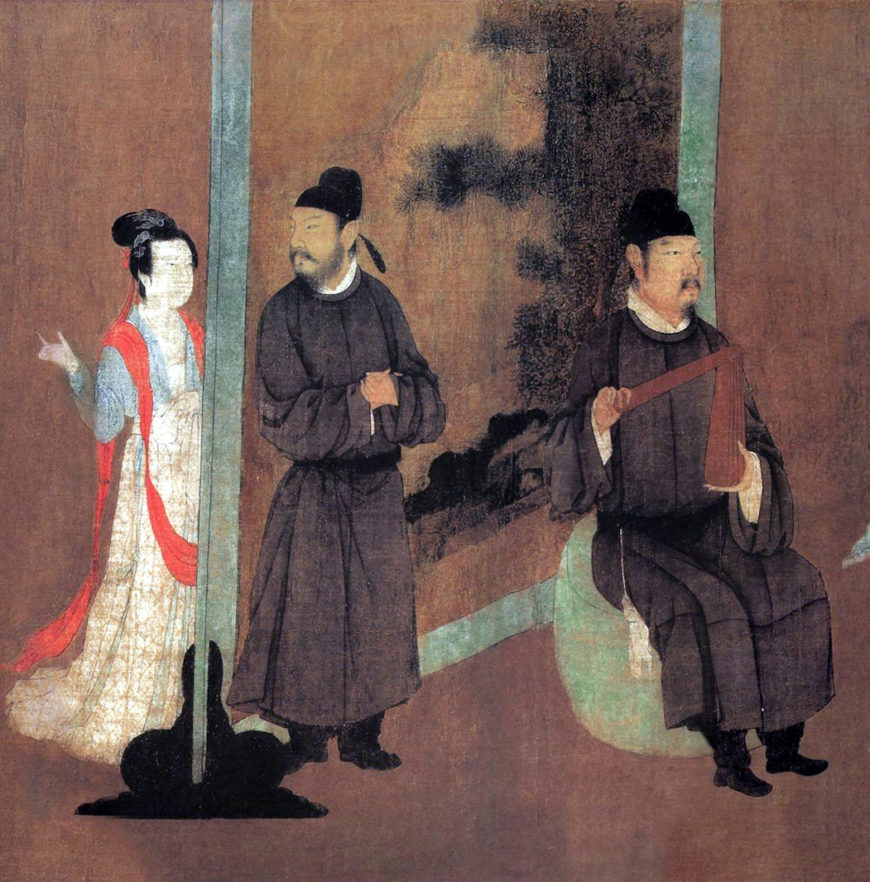

Gu Hongzhong, detail of Han with three ladies, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

In medieval China, the reputations of court officials followed them both inside and outside of the imperial palace. Respectable conduct reflected the loyalty of a subject to the emperor, while inappropriate behavior could provoke shame and embarrassment. At one point, the emperor Li Yu sought the help of Gu Hongzhong, who served as a court painter during the Southern Tang dynasty (937–975). Noting his skill in portraying figures, the emperor directed Gu to perform an unusual task: to spy on a well-known court minister—Han Xizai. Han attained a high rank and surrounded himself with dignified acquaintances. While he enjoyed an illustrious career, it reportedly soured after failed attempts at imperial reform. Han gained a bad reputation among courtly circles for wild parties, late-night debaucheries, and his obsession with beautiful singing girls. After spying on one of Han’s night banquets outside of the palace, Gu represented his impression of the evening in The Night Revels of Han Xizai. In the painting, Han gazes on as his guests play music and linger over food and drink, enjoying all the latest fashions while doing away with court decorum.

Gu Hongzhong, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

Gu Hongzhong, detail of the narrative scenes, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

The painting (alternately known as The Night Banquet of Han Xizai) offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the intrigues of court life during the Five Dynasties period (906–960), when several smaller dynasties and kingdoms—including the Southern Tang dynasty—vied for power following the fall of the Tang empire (618–907). Although the painting threatens to expose the behavior of a disillusioned official, it also may have served as an admonition to court officials who might be tempted to stray from upright conduct.

Gu Hongzhong, detail of the first scene showing Han seated on a couch (in black), The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

Portrait of a protagonist

The Night Revels of Han Xizai is mounted as a handscroll, which means that it is not hung on a wall, but rather unfurled length-by-length between the viewer’s hands. The painting is set in the interior of a mansion, where a late-night party is underway. In five scenes that are typically viewed from right to left, Han appears five times throughout the scroll, along with several court ministers, monks, and entertainers—many of whom have been identified by scholars. Gu first portrayed Han with other ministers and officials in Confucian robes, seated on a couch bed beside a table with small plates and beverages set out, while watching a woman play a pipa (lute).

Gu Hongzhong, detail of Han drumming with a dancing woman in blue, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

In following scenes, he is pictured drumming beside a dancing woman, washing his hands in a basin, listening to female musicians playing flute (top of the page), and finally bidding farewell to guests.

Gu Hongzhong, detail of Han waving good night, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

The Night Revels of Han Xizai is a figure painting but, even more specifically, it is a portrait. Gu pictured Han in hierarchal perspective (larger in scale relative to his guests and wearing a tall hat), indicating his importance as host and protagonist. Han appears somber and reserved, as if he were aware that the gathering might not be perceived favorably. Gu’s detailed painting seems like an eyewitness account, one that attests to the rumors about Han and his wild parties. At the same time, his portrayal of Han as somewhat aloof suggests that he may be conflicted by the demands of duty and pleasure.

Detail of screen with a guest playing a clapper while another turns his head to a young woman on the other side of a screen, who gestures to a moment of impropriety Gu Hongzhong, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

Contemporary fashion

Gu divided the scenes in the handscroll into groupings of figures, a visual practice seen in earlier paintings and murals, but with distinct attention to the furniture—screens and couch beds that characterized the fashionable interior of a mansion. The presence of couch beds, for instance, demonstrates the preference for raised seating, as opposed to sitting on mats on the floor. This practice evolved from furniture such as dais, stools, and armchairs seen along the Silk Road and also at the earlier Tang dynasty court. On the Silk Road, Buddhist monks carried folding chairs and it became common to sit on dais/elevated platforms when teaching Buddhist ideas.

Gu Hongzhong, detail of Han on a couch with guests (left) and a rumpled bed (right), The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

At times, Han is seated on the platforms to indicate his role as host, while in other instances, we see couch beds strewn with rumpled bedclothes to suggest erotic revelry. The images unfold in a continuous narrative, as opposed to a linear narrative, meaning that certain figures appear several times throughout the composition. Several moments of the evening are pictured, not necessarily in chronological order, indicating that guests are milling around an extravagant party that lasts late into the night. Entertainers gesture and dance, wearing silk robes with red sashes and lavish textile patterns, while large screens frame the figures with paintings of ethereal landscapes. Characterized by the alluring details of dress and interior design, the scenes offer a colorful counter narrative to Confucian court culture, which emphasized values of austerity, propriety, and order.

Confucian values

Why might an emperor care to depict what lies outside the imperial palace. While life outside the court was of great interest to the emperor, he was undoubtedly concerned about Han’s scandalous behavior because he belonged to the imperial court. This tumultuous period after the fall of the Tang dynasty, a unified and cosmopolitan empire, led many to reconsider virtue and integrity as principles for a harmonious society under Confucian rule (the ethical system first laid out by Confucius in the 6th century B.C.E.). As China fragmented into several dynasties and kingdoms, one of which was the Southern Tang, many blamed the fall of the previous Tang dynasty on the reckless habits of its last emperor. By exposing Han’s unsanctioned behavior to other highly ranked ministers at the court, the painting could suggest a didactic or moral meaning as official propaganda. Perhaps by calling out Han’s transgressions in this handscroll, the emperor may have persuaded Han and others to adjust their conduct and return to appropriate courtly behavior.

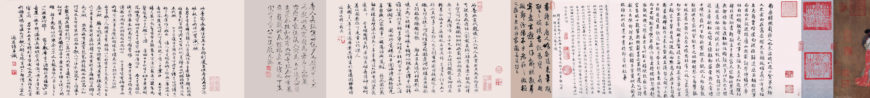

Gu Hongzhong, detail of colophons, The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

Today, the handscroll stands as a testament to the challenges of governing that characterized this tumultuous period. Colophons, or writings from later viewers and collectors, both precede and follow the handscroll and offer valuable insights into its social circulation up to the present. Even the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) emperor Qianlong added a colophon upon viewing the scroll, further attesting to its artistic and historical significance as an unofficial portrait. While noting the skill of Gu Hongzhong, Qianlong cautioned that the Palace and Minister had made themselves laughing-stocks in history and therefore the painting served as a warning against misconduct.

Wang Qingsong, The Night Revels of Lao Li, 2000, photograph, 31 ft (120 x 960cm) (The Victoria & Albert Museum)

The Night Revels in contemporary art

Recently, artists have revisited Gu’s tenth-century scroll painting not only because it offers a rare glimpse into a period from which few paintings survive, but also for its exploration of Confucian mores that still resonate in Chinese culture today. In one parody of Gu’s work, the artist Wang Qingsong created a 31-foot photomural, Night Revels of Lao Li. Shot with a large-format studio camera, Wang stitched the images together digitally into five scenes. He replaced the subject Han Xizai with the curator Li Xianting, who was removed as editor of an official art magazine in 1989 after championing risky work, and then became a fixture in bohemian Beijing.

Left: Wang Qingsong, The Night Revels of Lao Li, 2000, photograph, 31 ft (120 x 960cm) (The Victoria & Albert Museum); right: Gu Hongzhong, detail of the first scene showing Han seated on a couch (in black), The Night Revels of Han Xizai, handscroll, 12th-century (Song dynasty) copy of a 10th-century (Southern Tang dynasty) composition), ink and color on silk, 28.7 x 335.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing)

Following Gu’s compositional arrangement of figural groupings, Wang Qingsong depicted Li and guests enjoying contemporary instruments and food, such as Sprite and Coca-Cola. Entertainers wear flimsy, neon-hued outfits that allude to Gaudy Art, China’s version of Pop. One may also note the presence of an interloper (in the detail above, peeking out from behind the screen on the left)—this is the artist himself, Wang Qingsong, who effectively turns the unofficial portrait of Li into a self-portrait, where he is now cast as the detective (like Gu more than a thousand years earlier) who records the event for posterity. Both shocking and humorous in its portrayal of the frustrated career of curator Li, Wang’s Night Revels similarly portrays the protagonist’s entertainment as a response to official decorum and so questions the nature of China’s political progress.

A rare picture

Gu Hongzhong’s The Night Revels of Han Xizai offers an intriguing portrayal of a court minister testing the bounds of Confucian propriety during the Five Dynasties. The court minister Han’s nighttime revelry captured the attention and curiosity of the emperor, who, upon deputizing his court artist to document the situation, left us with a rare picture of the fashions and foibles of this tumultuous period of Chinese art—one that continues to inspire artists today.

Additional resources:

Lee, De-nin Deanna, The Night Banquet: A Chinese Scroll Through Time (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010).

Sullivan, Michael, The Night Entertainments of Han Xizai: A Scroll by Gu Hongzhong (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008).