Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains, ink on silk hanging scroll, c. 1000, 206.3 x 103.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Daoist mountain man, hermit, rustic, wine-lover—Fan Kuan has the reputation of having been truly unconventional. We know very little about this great artist, yet he painted the most majestic landscape painting of the early Song period. Everything about Travelers by Streams and Mountains, which is possibly the only surviving work by Fan Kuan, is an orderly statement reflecting the artist’s worldview.

Landscape as a subject

Fan Kuan’s masterpiece is an outstanding example of Chinese landscape painting. Long before Western artists considered landscape anything more than a setting for figures, Chinese painters had elevated landscape as a subject in its own right. Bounded by mountain ranges and bisected by two great rivers—the Yellow and the Yangtze—China’s natural landscape has played an important role in the shaping of the Chinese mind and character. From very early times, the Chinese viewed mountains as sacred and imagined them as the abode of immortals. The term for landscape painting (shanshui hua) in Chinese is translated as “mountain water painting.”

After a period of upheaval

During the tumultuous Five Dynasties period in the early 10th century (an era of political upheaval from 907–960 C.E., between the fall of the Tang Dynasty and the founding of the Song Dynasty, when five dynasties quickly succeeded one another in the north, and more than twelve independent states were established, mainly in the south), recluse scholars who fled to the mountains saw the tall pine tree as representative of the virtuous man. In the early Northern Song dynasty that followed, gnarled pine trees and other symbolic elements were transformed into a grand and imposing landscape style.

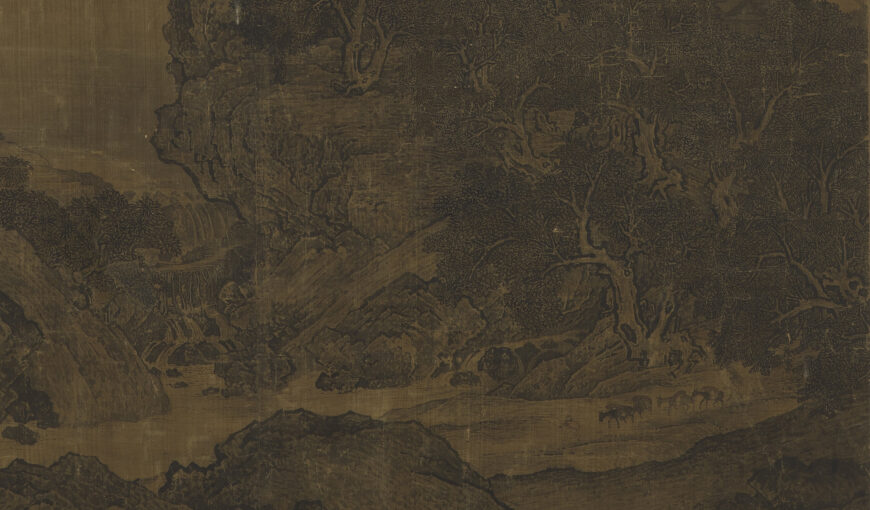

Gnarled pine trees and two men driving a group of donkeys (detail), Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains, c. 1000, ink on silk hanging scroll, 206.3 x 103.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Fan Kuan painted a bold and straightforward example of Chinese landscape painting. After the long period of political disunity (the Five Dynasties period), Fan Kuan lived as a recluse and was one of many poets and artists of the time who were disenchanted with human affairs. He turned away from the world to seek spiritual enlightenment. Through his painting Travelers by Streams and Mountains, Fan Kuan expressed a cosmic vision of man’s harmonious existence in a vast but orderly universe. The Neo-Confucian search for absolute truth in nature as well as self-cultivation reached its climax in the 11th century and is demonstrated in this work. Fan Kuan’s landscape epitomizes the early Northern Song monumental style of landscape painting. Nearly seven feet in height, the hanging scroll composition presents universal creation in its totality and does so with the most economic of means.

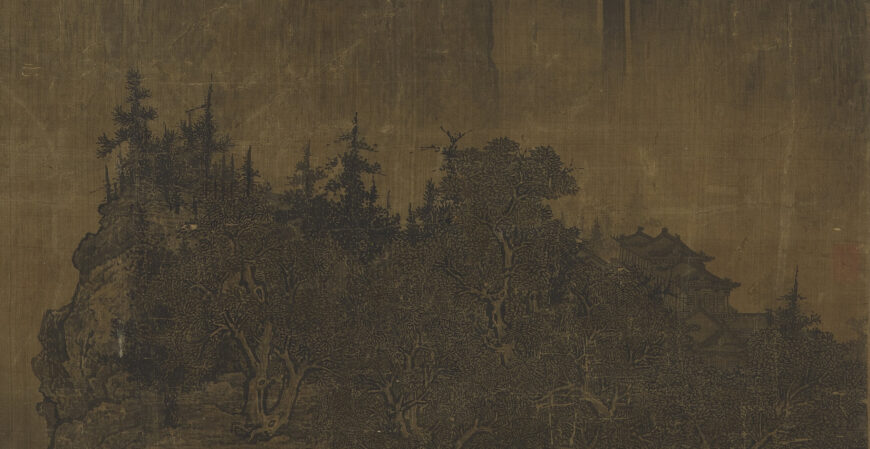

Temple in the forest (detail), Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains, c. 1000, ink on silk hanging scroll, 206.3 x 103.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Immense boulders occupy the foreground and are presented to the viewer at eye level. Just beyond them one sees crisp, detailed brushwork describing rocky outcroppings, covered with trees. Looking closely, one sees two men driving a group of donkeys loaded with firewood and a temple partially hidden in the forest. In the background a central peak rises from a mist-filled chasm and is flanked by two smaller peaks. This solid screen of gritty rock takes up nearly two-thirds of the picture. The sheer height of the central peak is accentuated by a waterfall plummeting from a crevice near the summit and disappearing into the narrow valley.

Central peak (detail), Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains, c. 1000, ink on silk hanging scroll, 206.3 x 103.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

The mountain form accurately captures the geological traits of southern Shaanxi and northwestern Henan provinces—thick vegetation grows only at the top of the bare steep-sided cliffs in thick layers of fine-grained soil known as loess. The mountains are triangular with deep crevices. In the painting they are conceived frontally and additively. To model the mountains, Fan Kuan used incisive thickening-and-thinning contour strokes, texture dots and ink wash. Strong, sharp brushstrokes depict the knotted trunks of the large trees. Notice the detailed brushwork that delineates the foliage and the fir trees silhouetted along the upper edge of the ledge in the middle distance.

Monumental landscape (detail), Fan Kuan, Travelers by Streams and Mountains, c. 1000, ink on silk hanging scroll, 206.3 x 103.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

To convey the sheer size of the landscape depicted in Travelers by Streams and Mountains, Fan Kuan relied on suggestion rather than description. The gaps between the three distances act as breaks between changing views. Note the boulders in the foreground, the tree-covered rock outcropping in the middle, and the soaring peaks in the background. The additive images do not physically connect; they are comprehended separately. The viewer is invited to imagine himself roaming freely, yet one must mentally jump from one distance to the next.

The unsurpassed grandeur and monumentality of Fan Kuan’s composition is expressed through the skillful use of scale. Fan Kuan’s landscape shows how the use of scale can dramatically heighten the sense of vastness and space. Diminutive figures are made visually even smaller in comparison to the enormous trees and soaring peaks. They are overwhelmed by their surroundings. Fan Kuan’s signature is hidden among the leaves of one of the trees in the lower right corner.

Neo-Confucianism

The development of Monumental landscape painting coincided with that of Neo-Confucianism—a reinterpretation of Chinese moral philosophy. It was Buddhism that first introduced, from India, a system of metaphysics and a coherent worldview more advanced than anything known in China. With Buddhist thought, scholars in the 5th and 6th centuries engaged in philosophical discussions of truth and reality, being and non-being, substantiality and non-substantiality. Beginning in the late Tang and early Northern Song, Neo-Confucian thinkers rebuilt Confucian ethics using Buddhist and Daoist metaphysics. Chinese philosophers found it useful to think in terms of complimentary opposites, interacting polarities—inner and outer, substance and function, knowledge and action. In their metaphysics they naturally employed the ancient yin and yang. The interaction of these complementary poles was viewed as integral to the processes that generate natural order.

Central to understanding Neo-Confucian thought is the conceptual pair of li and qi. Li is usually translated as principles. It can be understood as principles that underlie all phenomena. Li constitutes the underlying pattern of reality. Nothing can exist if there is no li for it. This applies to human conduct and to the physical world. Qi can be characterized as the vital force and substance of which man and the universe are made. Qi can also be conceived of as energy, but energy which occupies space. In its most refined form it occurs as mysterious ether, but condensed it becomes solid metal or rock.

Not as the human eye sees

The Neo-Confucian theory of observing things in the light of their own principles (li) clearly resonates in the immense splendor of Fan Kuan’s masterpiece. Northern Song landscape painters did not paint as the human eye sees. By seeing things not through the human eye, but in the light of their own principles (li), Fan Kuan was able to organize and present different aspects of a landscape within a single composition—he does this with a constantly shifting viewpoint. In his masterful balance of li and qi, Fan Kuan created a microcosmic image of a moral and orderly universe.

Fan Kuan looked to nature and carefully studied the world around him. He expressed his own response to nature. As Fan Kuan sought to describe the external truth of the universe visually, he discovered at the same time an internal psychological truth. The bold directness of Fan’s painting style was thought to be a reflection of his open character and generous disposition. His grand image of the beauty and majesty of nature reflects Fan Kuan’s humble awe and pride.

Note from author: With tremendous debt to my teacher Wen Fong.