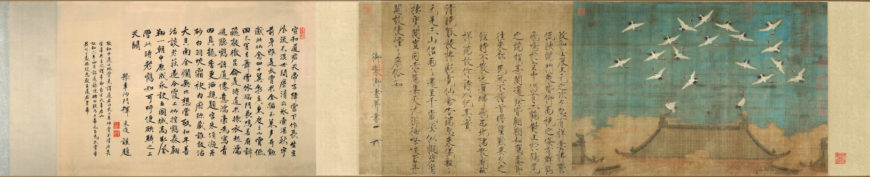

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes (detail), 1112, Northern Song dynasty, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 51 x 138.2 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang)

A flock of twenty cranes fly against a blue sky, while rolling clouds encircle the roof tiles and ornaments of the city gates below. The image records an auspicious event (a sign of good fortune) witnessed over the capital city of Kaifeng in 1112, as indicated by an inscription and poem by Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) to the left of the painting. Huizong was widely regarded as an ineffective ruler, and his reign hastened the fall of the country to invaders from the north. As if to counter the reality of his poor statesmanship, the painting conveys an image of harmony between nature and humanity—the good omen of cranes emerges from clouds (nature) over the architecture of the capital (the human world). The painting, followed by an inscription and poem, together comprise Auspicious Cranes and suggest that the emperor (like all emperors) held the “Mandate of Heaven,” or the heavenly right to rule (tīanmìng 天命).

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes, 1112, Northern Song dynasty, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 51 x 138.2 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang)

Auspicious imagery

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes (detail), 1112, Northern Song dynasty, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 51 x 138.2 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang)

Mounted on a handscroll that unfurls from right to left, Auspicious Cranes is laid out like a historical document, one that records a natural phenomenon that was interpreted as a good omen for the dynasty. Each pictorial element appears stylized and descriptive—for instance, the flying cranes are pictured with their wings flattened and outstretched, and their legs are rendered as a pair of near parallel lines, recalling motifs seen in tomb murals or textiles (both earlier and later, such as a Portrait of Minister Gu Lin from 1544). This visual mode speaks to both the veracity and otherworldliness of the sighting, in that it accurately portrays the recognizable features of each element but does not characterize them with a lifelike demeanor.

As the inscription reveals, the actual event began in 1112 with a sighting of auspicious clouds over Kaifeng. Clouds and mists represent the vital forces of the universe (qì 氣) in Daoist thought. As residents of the city beheld the extraordinary sight of the clouds, a flock of cranes descended from the clouds and formed over the rooftops—a sign that all was in accord under Heaven.

Auspicious images appear as early as the first paintings in China, as seen on tombs, textiles (such as Lady Dai’s funeral banner), and murals, and typically embody multiple wishes for good outcomes. They rely on symbols (such as cranes that evoke long life and immortality), to characterize a particular moment or event. Auspicious images may appear in images created in honor of weddings, retirements, or farewells, and other significant occasions, both to delight the eye and offer a blessing. It is possible that certain auspicious images may correspond to traditions and rituals at the court, such as music and dances. Some also may be efficacious, meaning that the images were believed to have embodied the omens and so could bring into being the wish itself.

Emperor Huizong, Auspicious Cranes (detail), 1112, Northern Song dynasty, handscroll, ink and color on silk, 51 x 138.2 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang)

To emperor Huizong and his subjects, the sight of clouds and cranes likely signaled a blessing of peace and harmony in the empire. Following the painting of Auspicious Cranes, the inscription and poem recount the moment that the common people witnessed the clouds and cranes materialize over the imperial palace. The text describes people bowing in reverence to the unusual sight, and the gestures of onlookers could be understood as bolstering the legitimacy of the emperor’s reign.

Only those close to the emperor would have seen this work, such as highly-ranked members of the court who may have had doubts about Huizong’s capabilities as a ruler. Considering the importance of capturing this image in words and pictures, along with what historians have described of Huizong’s incompetency, it seems that he greatly welcomed this sign of good luck.

The imperial brush

The inscription and poem accompanying Auspicious Cranes expand our understanding of the picture and its historical context. The calligraphy is composed in “slender gold script,” a style of writing demonstrated by firm, thin strokes with crisp, elegant brushstrokes—like melted gold applied by brush. Slender gold script is specifically associated with Huizong, and therefore conveys the prestige and authority of the emperor. Moreover, the signature notes that it is signed with the “imperial brush” of the emperor (yubi 御筆). Although Huizong did not always write or even sign the works himself, the imperial brush is a mark of his agency. In other words, other officials or even palace ladies may have composed works in the slender gold script under Huizong’s direction and to serve his purposes. Such works, typically poems, nonetheless bear the mark of the imperial brush, and therefore they are still considered to be works by Huizong.

The legacy of Emperor Huizong

While Emperor Huizong is regarded as an utter failure who contributed to the end of the Northern Song dynasty, his interest in painting, poetry, and calligraphy (“the three perfections”) laid the foundation for new levels of artistic expression. To this end, he first assembled an enormous imperial collection of painting, calligraphy, and antiquities from the past, which served as a foundation for the rigorous study of classical traditions. He then invited leading artists throughout the empire to come to work at the palace workshops, institutionalizing painting traditions and recognizing painting as a respected profession. Scholars have suggested that Auspicious Cranes reflects the elegant style of the Imperial Painting Academy (the artists who worked for the Northern Song court). Moreover, emperor Huizong used painting, poetry, and calligraphy to capture this auspicious sighting in an image that still defines his legacy today.

Additional resources:

Maggie Bickford, “Emperor Huizong and the Aesthetic of Agency,” Archives of Asian Art 53, no. 1 (2003): pp. 71–104.

Peter C. Sturman, “Cranes Above Kaifeng: The Auspicious Image at the Court of Huizong,” Ars Orientalis 20 (1990): pp. 33–68.