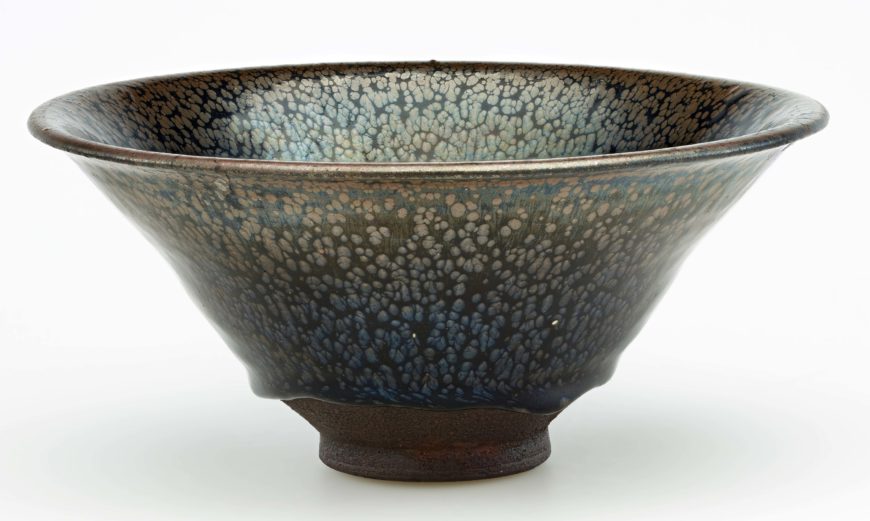

Bowl, Northern Song or Southern Song dynasty, 12th century, Jian ware, stoneware with iron-pigmented glaze, China, Fujian province, 8.8 x 19.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1909.369)

When the Tang dynasty (618–907) collapsed, a period of upheaval, rapid succession of dynasties, and multiple kingdoms followed. In the mid-tenth century, a general named Zhou Kuangyin reunified China, establishing the Song dynasty (960–1279) with himself as the first ruler, Emperor Taizu. The Song dynasty was divided into two periods: the Northern Song (960–1126), the physically larger empire, and the Southern Song (1127–1279). Overall, it was a time of stability and economic, cultural, and artistic prosperity.

Increased population, advanced agricultural techniques, and booming trade and commerce led to a thriving economy during both the Northern and Southern Song. The world’s first governmental paper money was issued in the 1120s. Despite the empire’s many successes, the state lacked the same degree of military strength that the previous Tang dynasty had enjoyed. Instead, the Song rulers took advantage of the empire’s economic strength and made large annual gifts to neighboring states to secure the peace that its armies could not. Despite the payoffs, a seminomadic people called the Jurchens eventually conquered the capital of Kaifeng in 1126, bringing an end to the Northern Song. The Song court fled south and established a new capital in the city that is today known as Hangzhou, beginning what is called the Southern Song dynasty.

The Song government’s relative military weakness was disturbing to many Chinese intellectuals. They developed a defensive, inward-looking strategy and became less open to adopting foreign styles and ideas. Buddhism, for example, was to some degree rejected for its foreign origin, and the native philosophies of Confucianism and Daoism experienced a strong resurgence. With the Confucian revival came a new interest in ancient culture, or antiquarianism. The Song dynasty is often called an age of protoarchaeology and a period when great collectors and connoisseurs of art flourished both in and outside the court. Pre-Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.) bronzes and jades began to be collected and were imitated and reproduced in creative new interpretations. Reverence for and reference to the past became increasingly important factors in Chinese art.

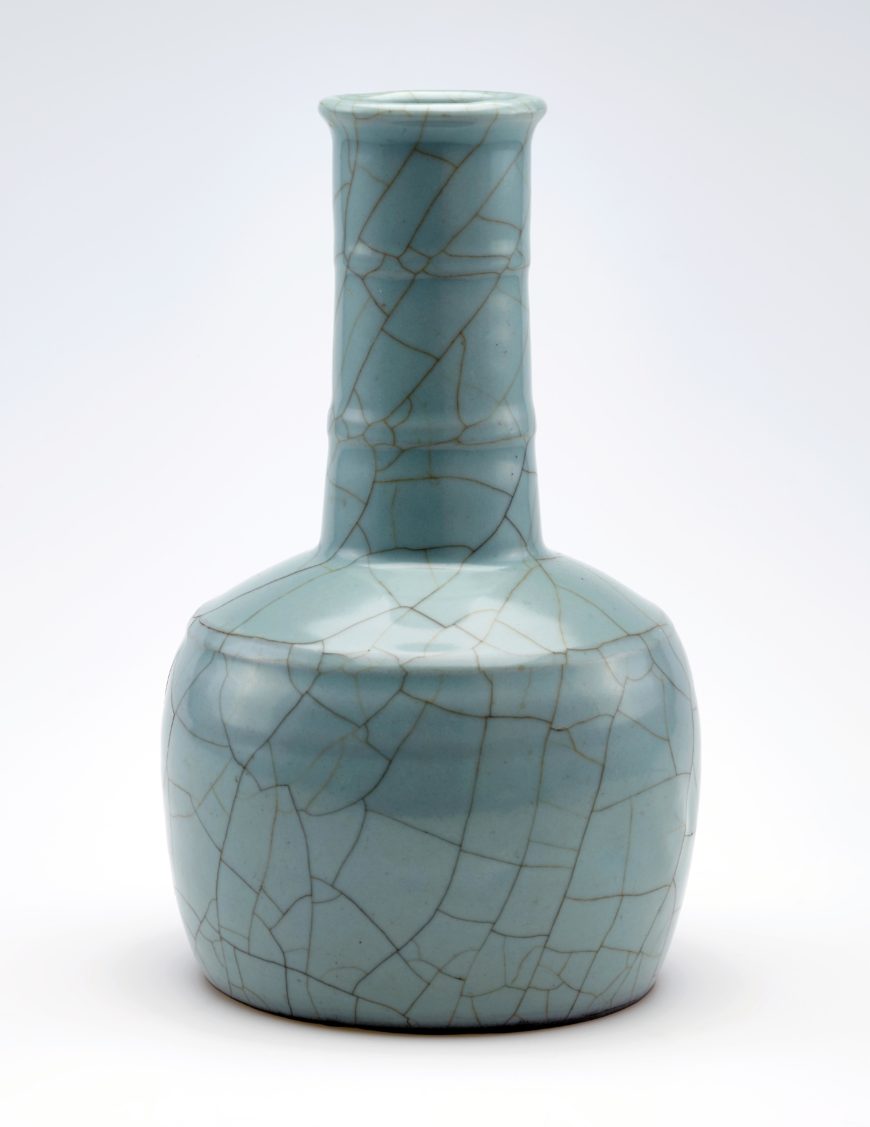

Guan ware long-necked vase with raised bow-string decoration, Southern Song dynasty, 12th century, Guan ware, stoneware with Guan glaze, China, Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, Jiaotanxia kiln, 23.2 x 14.1 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1911.338)

Ceramics made in the Song dynasty stand out as world masterpieces. Song ceramics were supremely accomplished in terms of technical expertise, creativity, and the aesthetic harmony between the shape and glaze of a vessel. The Song court favored elegant ceramics with simple and refined forms and subtle gazes, reflecting the aesthetic values and introspective atmosphere of the time. Alongside the simpler ceramics that suited court tastes, the popular market was extremely vibrant and productive in making ceramics with bold designs and multiple colors.

The Song court established an Imperial Painting Academy in the palace. Painters from all over the country were recruited to serve the needs of the court. The varied traditions, under the auspices of the court, blended together into a distinctive Song academic style. It valued a naturalistic and descriptive representation of the physical world. Scholar officials chosen through the civil service examination also had a major impact on the arts. They developed a style that rejected the descriptive realism of the professional and court painters, valuing spontaneity and a type of brushwork that was informed by their study of calligraphy. Many favored painting in ink alone without color. For the scholar (or amateur) artists, painting was a means of personal expression pursued for the enjoyment of the artist and for the sharing of ideas with his circle of friends.

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation