Church and Reliquary of Sainte-Foy, France: A gold, gem-encrusted reliquary attracted both pilgrims and wealth to the sleepy medieval village of Conques.

Read Now >Chapter 39

Late medieval multimedia and devotion

If you take a poll of scholars and ask, “what was the most important change that marked the transition away from medieval visual culture in northern Europe?,” you’d likely receive responses like the “printing press” or “self-portrait.” To be sure, art historians tend to focus on innovation. We like to pinpoint concrete moments of great change to nicely divide epochs. However, it is not like anyone woke up one morning in the fifteenth century and suddenly declared, “today starts a new era called early modern.” Rather, the periods typically defined as “medieval” and “early modern” overlapped in the fifteenth century; not in any sense does one epoch simply end and the other begin.

Michael Pacher, Sankt Wolfgang Altarpiece, 1471–81, polychrome pine, linden, gilding, oil, over 40 feet high and more than 20 feet wide, Parish Church, Sankt Wolfgang, Austria

This chapter looks at a crucial overlapping theme of late medieval and early modern northern Europe: how the multimedia image shaped Christian devotional practices from c. 1300–1520. After reading this chapter, you’ll gain an understanding of the function and meaning of objects used to guide prayer and contemplation in Christian visual culture. These objects were often complex, richly layered, and employed more than one artistic material—such as the combination of painting and sculpture. Hence, the term multimedia.

The periods of focus in this chapter witnessed significant social and religious transformations leading up to the Protestant Reformation. Within this timeframe, you will see how the proliferation of devotional images for private and public consumption necessitated the regulation and control of religious images—especially three-dimensional ones.

Medieval Three-Dimensional Devotional Images

Reliquary statue of Sainte-Foy (Saint Faith), late 10th to early 11th century with later additions, gold, silver gilt, jewels, and cameos over a wooden core, 33 1/2 inches (Treasury, Sainte-Foy, Conques) (photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The relationship between religious subject matter and the medium of sculpture is central to understanding Christian veneration in northern medieval Europe. Medieval devotional images were often used to complement and extend Christian scripture. How to appropriately translate the word of God into an image, however, was hotly debated throughout the Middle Ages. The primary source on the role of images comes from the Second Commandment in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, which states:

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven images or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God . . . (Exodus XX, 4–5)

Among all artistic media, sculpture was thought to most closely verge on idolatry (the worship of an idol or image of God). Because sculpture exists as a three-dimensional presence in direct relation to the viewer, sculpture could easily be confused as a holy figure rather than a representation or prototype of a holy figure. As a result, church authority sought to regulate sculpture in public spaces such as the interior of churches, where sculpture encompassed different functions for worship or memorial remembrances. In private settings of worship, the church had less control over the content of devotional images.

The objects in this section reflect the range of sculpted images related to Christian devotional practices. A popular embodiment of church-approved pre-Reformation piety was the cult of relics (the material remains or an object physically associated with a Christian martyr). Sumptuously gilded and opulent reliquary sculptures were created to honor, protect, and contain relics, such as the enshrined reliquaries of Ste. Foy and the Virgin of Jeanne D’Evreux.

Röttgen Pietà, c. 1300–25, painted wood, 34 1/2″ high (LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn) (photo: Ralf Heinz, with permission)

Other free-standing sculptures in the church space were meant to entice the Christian viewer. The Röttgen Pietà depicts the gruesome aspects of Christ’s death to elicit an emotional connection.

St. George and the Dragon, Storkyrkan Stockholm, c. 1490 (photo: Alexey M., CC BY-SA 4.0)

The St. George and the Dragon sculpture in the Storkyrkan in Stockholm translates a complex narrative into an over-life-size three-dimensional image, resulting in a highly dynamic relationship between the viewer and the religious imagery within the church space.

Watch videos and read essays medieval three-dimensional devotional images

The Virgin of Jeanne d’Evreux: Mary’s swaying hip, elongated neck, and tender touch of the Christ Child all imbue this golden sculpture with grace. A pomegranate signals death.

Read Now >

Röttgen Pietà: Focusing on the gruesome aspects of Christ’s death helps to elicit an emotional connection.

Read Now >

St. George and the Dragon, Storkyrkan Stockholm: A massive, over-life-sized sculptural group of St. George and the Dragon in the City Church of St. Nicholas, Stockholm reads like a fairy tale.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Multimedia Winged Altarpieces

Hermen Rode, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (final view completely open), 1478–1481, Tallinn (Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn)

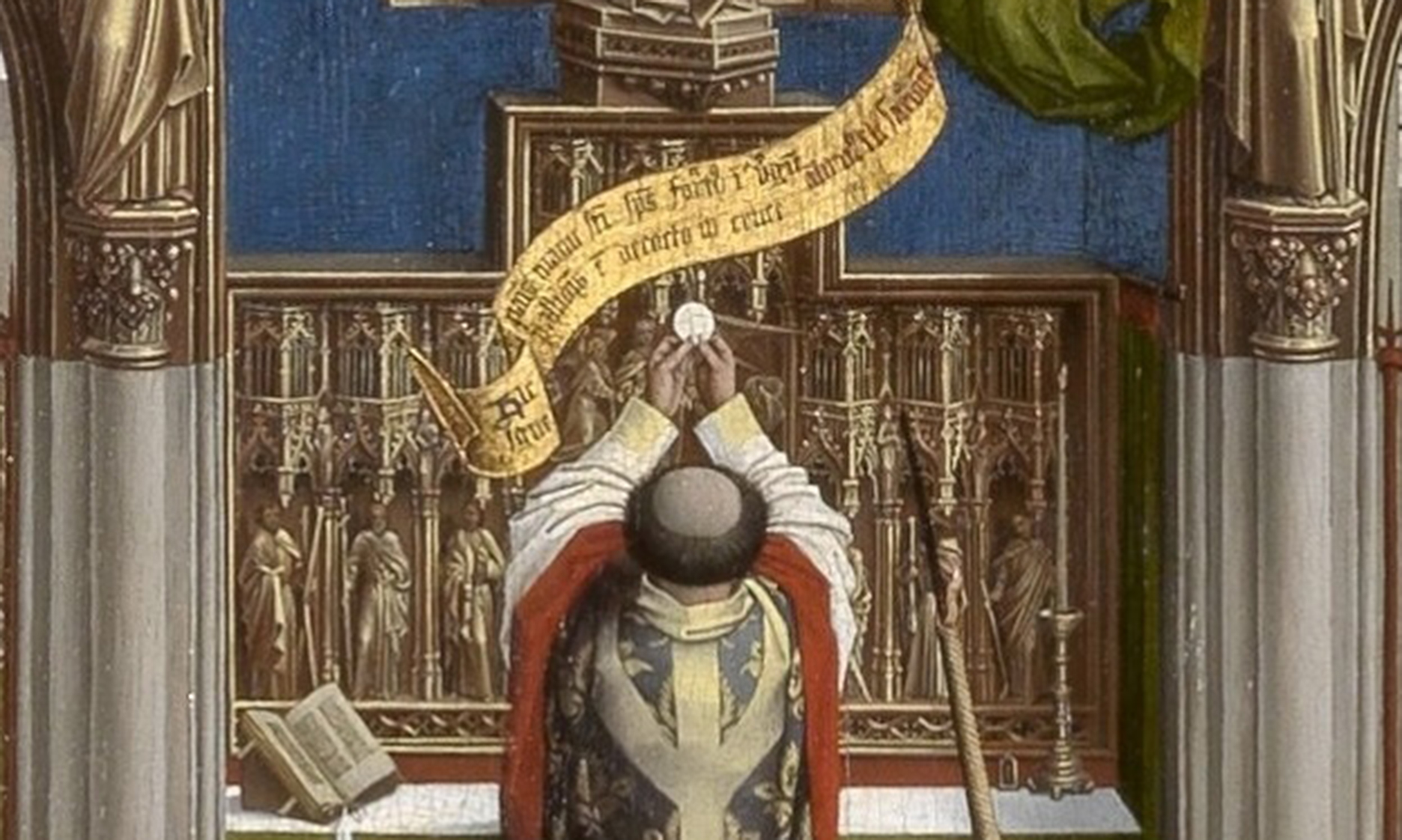

In addition to free-standing sculpture, the altarpiece was perhaps the most common form of three-dimensional devotional art in churches. Installed on nearly every altar in pre-Reformation northern Europe, altarpieces primarily served to enhance the Mass ritual (the central act of Christian worship). This section considers how the altarpiece dually worked to promote and control sculpture.

A specific configuration of the altarpiece included wings. The organization of the winged altarpiece predominantly places sculpture at its center, flanked by a set of hinged doors that open and close. The wings also allowed the Christian clergy to regulate the viewing of sculpture, such that the central sculpture was exposed only on the most holy days of the Christian liturgical calendar. Indeed, the rare appearance of sculpture enhanced its power as seemingly divine, exacerbating the conflation between saintly subject and object.

Shrine of the Virgin, c. 1300 (German), oak, linen covering, polychromy, gilding, gesso, open: 36.8 x 34.6 x 13 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Early appearances of the winged altarpiece structure can be seen in an enclosed sculpture of the Shrine of the Virgin. The versatility of winged altarpieces attracted a wide audience of users and patrons from dukes to merchants, and further allowed artists to play with size, measuring from miniature to massive. Altarpieces like Michael Pacher’s or Hermen Rode’s demonstrate the flexibility of the winged altarpiece to cater to specific groups and wealthy nobles. The sixteenth-century miniature altarpiece is another expression of the adaptability of the altarpiece’s winged form in the early modern globalized world.

Watch videos and read essays about multimedia winged altarpieces

The Medieval and Renaissance Altarpiece: The story embodied on the altarpiece offered an object lesson in the human suffering experienced by Christ.

Read Now >

Michael Pacher, St. Wolfgang Altarpiece: It unites sculpture, painting, and architecture—and connects real space to a visionary realm.

Read Now >

Hermen Rode, Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece: The Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece stands as a rare example of a high altarpiece that remains in its original location since its installation in 1481.

Read Now >

Pendant triptych with scenes of the Passion: A Renaissance miniature in wood and feathers.

Read Now >/5 Completed

The Early Netherlandish Triptych

Workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), c. 1427–32, oil on oak panel, open 64.5 x 117.8 cm, central panel 64.1 x 63.2 cm, each wing 64.5 x 27.3 cm (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The early Netherlandish triptych became wildly popular in the fifteenth century. Patrons far outside The Netherlands commissioned this distinct type of painted altarpiece. Although missing carved sculpture in the center, early Netherlandish triptychs ultimately responded to the pre-established form of multimedia winged altarpieces with hinged wings.

Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece (open), completed 1432, oil on wood, 11 feet 5 inches x 15 feet 1 inch (open), Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium. Note: Just Judges panel on the lower left is a modern copy (photo: Closer to Van Eyck)

The Ghent Altarpiece closing (simulation, 0:06)

The Ghent Altarpiece, a massive polyptych, likely had a carved baldachin to closely mimic the structure of altarpieces with a carved center.

Saint John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist are the two centered figures on the bottom register, painted in grisaille. Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece (closed), completed 1432, oil on wood, 11 feet 5 inches x 7 feet 6 inches (closed) (Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium) (photo: Closer to Van Eyck)

In the closed view, the figures of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist are painted in grisaille (grey monochrome rendered to appear like unpainted stone sculpture), and stand as examples of how artists could grapple with the representational differences between painting and sculpture.

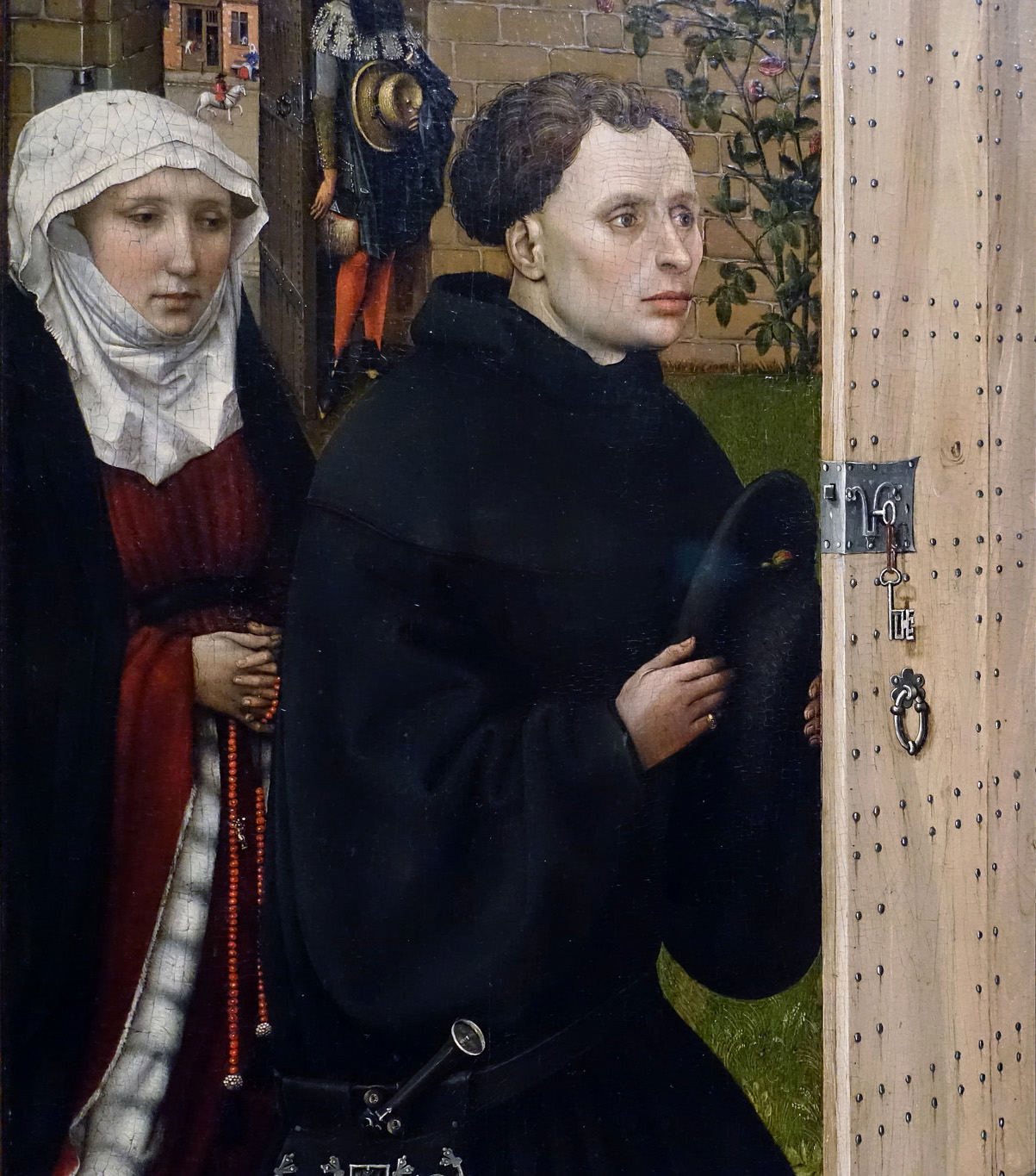

Robert Campin, Merode Altarpiece (detail), 1425-28, tempera and oil on panel (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The Merode Triptych features visual references designed to draw attention to the structure of the triptych with side panels that open and close like doors. In the left panel, the patron holds keys to unlock the door to the interior and a figure enters through a door into the enclosed courtyard.

Watch videos and read an essay about early Netherlandish triptychs

Jan Van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece: The altarpiece itself is a visual “moveable feast,” made up of 12 panels that fold against themselves.

Read Now >

Workshop of Robert Campin, Merode Altarpiece: It features visual references designed to draw attention to the structure of the triptych,

Read Now >/2 Completed

Fear of Death and Dying

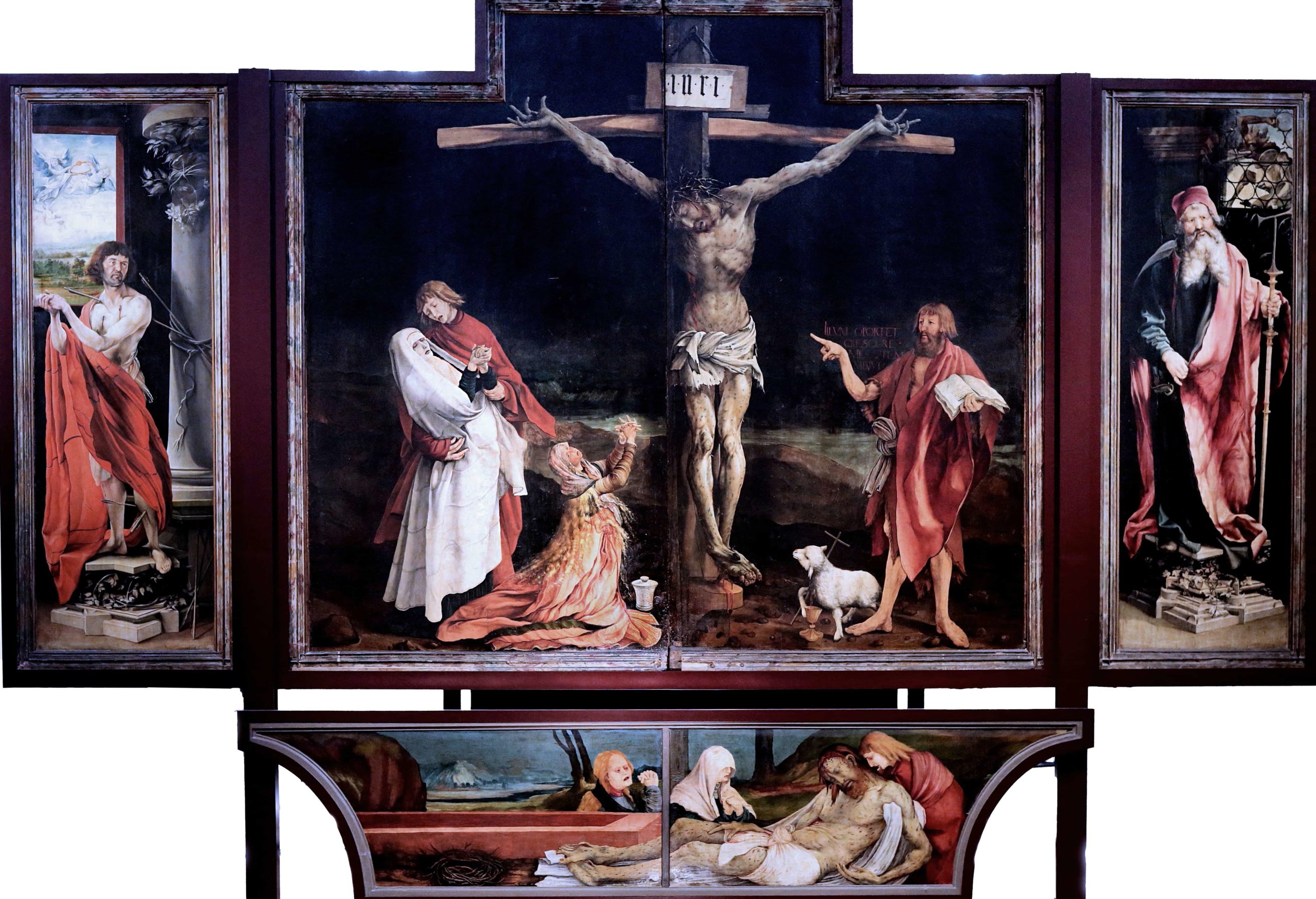

The notion that the devotional image was imbued with power posed a crisis during the Reformation. Two large-scale altarpieces—Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece and Bosch’s Last Judgment Triptych—made right before the momentous Protestant Reformation, attest to the growing anxieties on the efficacy of prayer and worship to secure a place in heaven.

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, view in the chapel of the Hospital of Saint Anthony, Isenheim, c. 1510-15, oil on wood, 9′ 9 1/2″ x 10′ 9″ (center panel) (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France)

The Isenheim Altarpiece was made for a viewing community infected with ergotism. The macabre image program relates to the ability of art to guide salvation, as well as to potentially heal and cure.

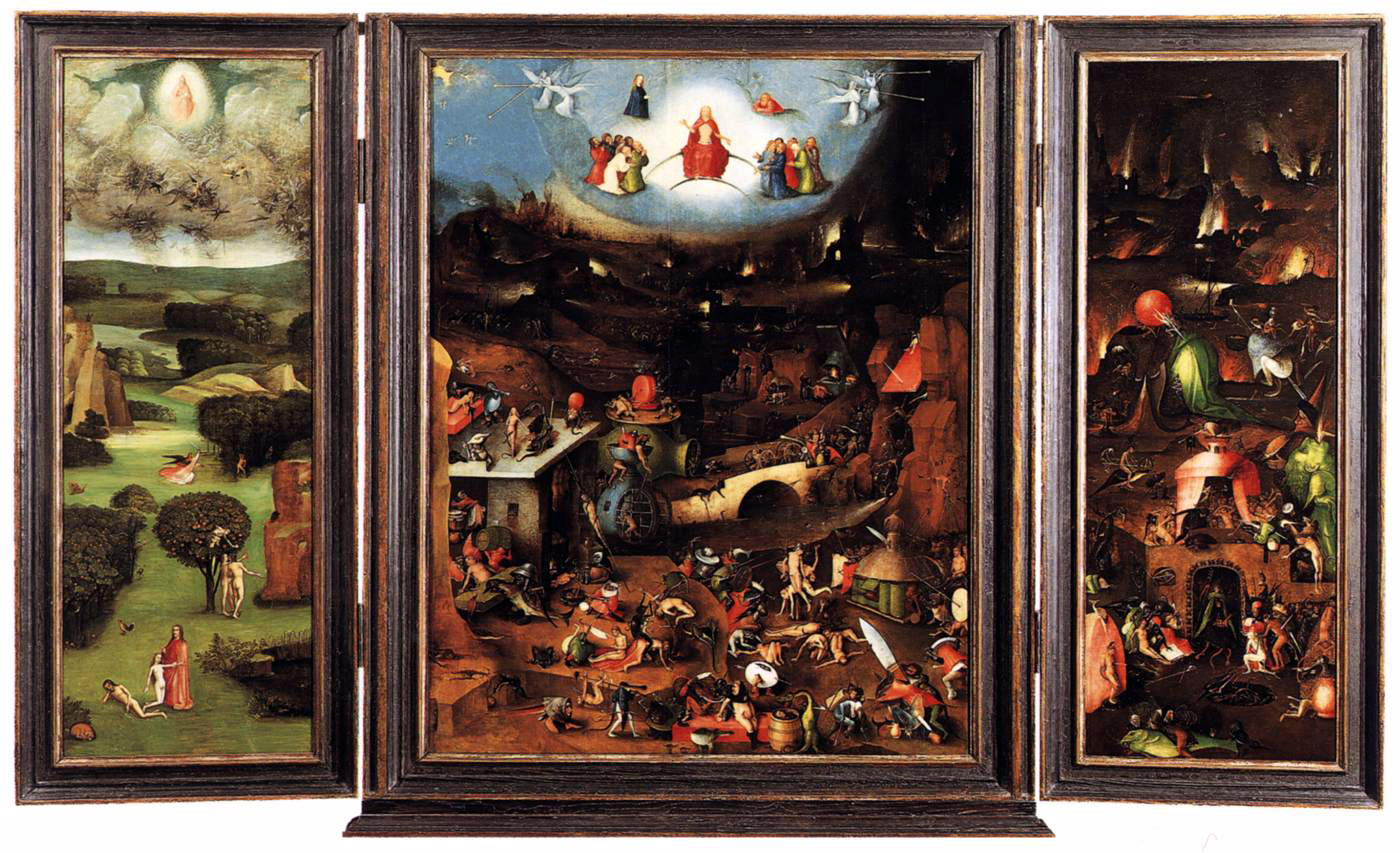

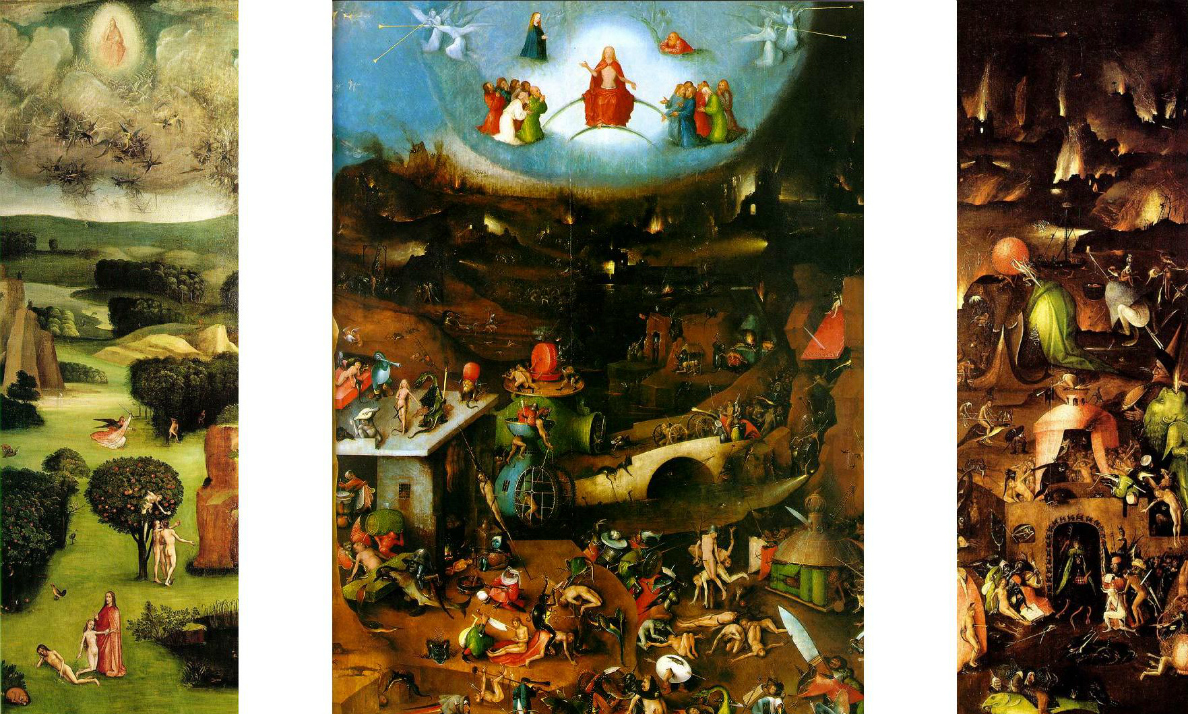

Hieronymus Bosch, Last Judgment Triptych, 1504–08, overall dimensions 163 x 250 cm, central panel 163 x 128 cm, wings 163 x 60 cm (Akademie für bildenden Künste, Vienna)

For artists like Bosch, humanity is inherently sinful and needs holy figures for salvation. Bosch became highly critical of clerical powers, and his Last Judgment Triptych represents a world overrun with demons, which only the strongest and rarest of people can resist. He paints a gruesome and grotesque world, yet such dark iconography has its roots in hell mouths and apocalyptic scenes as seen in earlier medieval art.

Watch a video and read an essay about art related to death and dying

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece: The macabre and distorted Christ is splayed on the cross, his hands writhing in agony, his body marked with livid spots of pox.

Read Now >

Hieronymus Bosch, Last Judgment Triptych: Bosch’s seemingly endless representations of pain and suffering betray his dark vision.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Fragments

Today we mostly see Netherlandish art as flat paintings installed on museum walls. However, many surviving panel paintings are fragments of deconstructed multimedia ensembles.

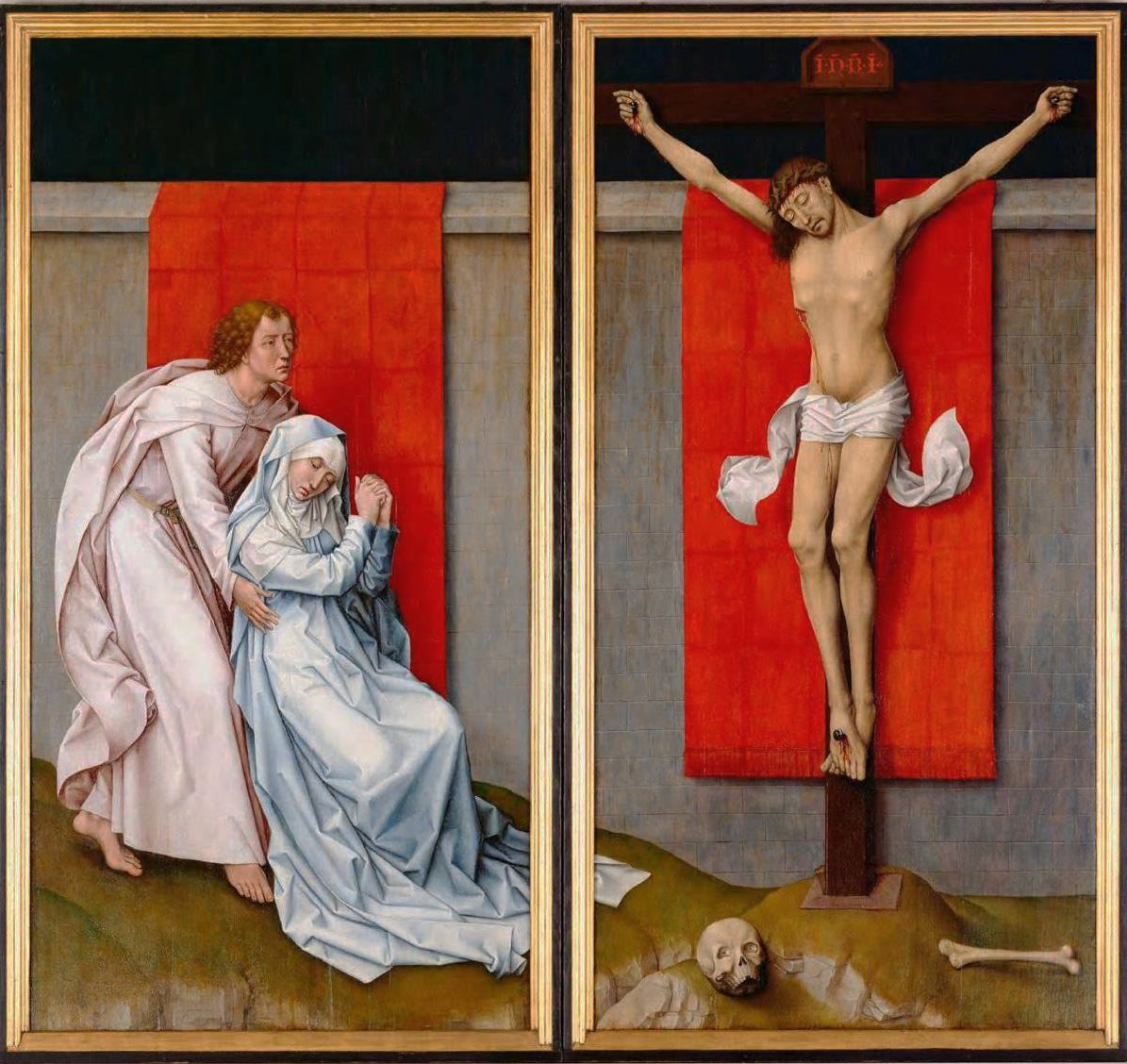

Rogier van der Weyden, The Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning (companion paintings), c. 1460, oil on panel, left panel 180.3 × 92.2 cm, right panel 180.3 × 92.5 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Painted panels by Rogier van der Weyden of the Crucifixion, with the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist were once part of a very large altarpiece with a now-lost sculpted center. The fact that more painting than sculpture has survived is often the result of modern interventions, such as the dismantling of multimedia altarpieces for the art market in the nineteenth century.

Iconoclasm, the intentional destruction of images, serves as another cause for the loss of sculpture. Sculpted images were especially attacked during the Iconoclasm of 1566 in The Netherlands, also known as Beeldenstorm (Dutch for “image storm”). Protestant theologians remained highly skeptical of the power of devotional objects—including both painting and sculpture—noting that the veneration of physical objects bordered on idolatry. Such ramifications of Protestant practice meant that devotional sculpture, a three-dimensional physical object, was targeted first during destructive waves of iconoclasm in the sixteenth-century Netherlands.

Watch a video about fragments

Rogier van der Weyden, Crucifixion Triptych: What remains is but a fragment of a once larger altarpiece.

Read Now >/1 Completed

The devotional and multimedia image stands as one of many artistic threads that reveal the gradual shift away from medieval religiosity into early modernity. Others include the growing sense of artistic self-awareness, in which artists confidently asserted their individual authorship. Artists also started traveling for work more frequently, often under court patronage or part of workshop training. Although artistic identity and mobility became hallmarks of the expanded world in early modernity, they were ultimately born out of late medieval artistic culture.

Key questions to guide your reading

How do three-dimensional and two-dimensional images differ?

How were multimedia images used for Christian devotion?

Why did religious images provoke anxiety leading up to the Protestant Reformation?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow do three-dimensional and two-dimensional images differ?

How were multimedia images used for Christian devotion?

Why did religious images provoke anxiety leading up to the Protestant Reformation?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

painting: two-dimensional, painted image

sculpture: three-dimensional, carved or sculpted image

Second Commandment

idol

idolatry

prototype

veneration

worship

winged altarpiece

Learn more

Read a chapter about Northern art in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Read a chapter about different materials in the medieval Mediterranean.

If you want to learn more about the Reformation, check out: Introduction of the Protestant Reformation.

If you want to know more about the destruction of images, check out: Iconoclasm in the Netherlands in the Sixteenth Century.