The Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 49

Printing and painting in Northern Renaissance art

Welcome to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in Northern Europe, the era of New Art or ars nova. What was new in this era? Plenty! Artists were examining the physical world in a way that earlier artists, who focused on the spiritual world, did not.

Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon van der Paele, 1436, oil on panel, 160 x 124.5 cm (Museum: Groeninge Museum Bruges)

Artists such as Jan van Eyck looked carefully at natural and human-made objects and used oil paint to evoke textures compellingly. New media allowed the production of images in multiples for the first time, and the Reformation rocked long-held religious and even political beliefs.

Martin Schongauer, Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, c. 1475, engraving, 30.0 x 21.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This chapter focuses on the varieties of media of the so-called Northern Renaissance, especially the invention of printing methods around 1450 that allowed pictures to be produced in multiples rather than one at a time. Such an expansion of pictures and information across wider swaths of populations allowed people in Northern Europe to learn about Italian ideas and vice versa. The rate of change is comparable to the exponential spread of information made possible with the arrival of the digital age. The skilled use of oil paint also allowed Northern artists to create uncanny illusions of reality.

Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

This chapter also focuses on the Lutheran Reformation which began in Wittenberg Germany in 1517, as an attack against the corruption of Catholic teaching. Inexpensive, mechanically reproducible media, such as woodcuts and engravings, powerfully dispersed the ideas of the Lutheran Reformation. The Reformation questioned the very legitimacy of religious imagery by proposing that sacred art was a form of idolatry. The Reformation also questioned the authority of the singular church in western Europe, and motivated the Catholic church to mine the Americas, Asia, and Africa for new members and sources of wealth. For these reasons, didactic oil paintings such as Cranach’s various versions of Law and Gospel—the earliest of which date from 1529—also anchored Lutheran ideas in places of public worship, replacing the devotional function of more traditional altarpieces.

This chapter considers four key issues regarding the Northern Renaissance, beginning with a questioning of the term itself:

- Was there a Northern Renaissance?

- The properties of oil paint that allowed artists to create illusions of reality

- The influence of mechanically reproducible media (prints)

- The transformational impact of the Protestant Reformation

Read an introductory essay

/1 Completed

Was there a (Northern) Renaissance?

Traditional timelines show the Renaissance beginning around 1400. The term Renaissance means rebirth, but what was reborn? According to fifteenth-century scholars (such as Leon Battista Alberti) and the wealthy bankers (particularly the Medici in Florence) who supported them, classical antiquity came back to life in the city of Florence. “Classical antiquity” refers to the cultural achievements of ancient Greece and Rome. Artists and architects in Italy were geographically closer to the material remains of the ancient world, so much Renaissance art responded to that proximity. The visual reminders of the ancient world were more sparse North of the Alps. Even though the ruins of Rome were fewer in Northern Europe, there was no real belief in a death and rebirth of antiquity. Instead, the site of classical culture simply changed location.

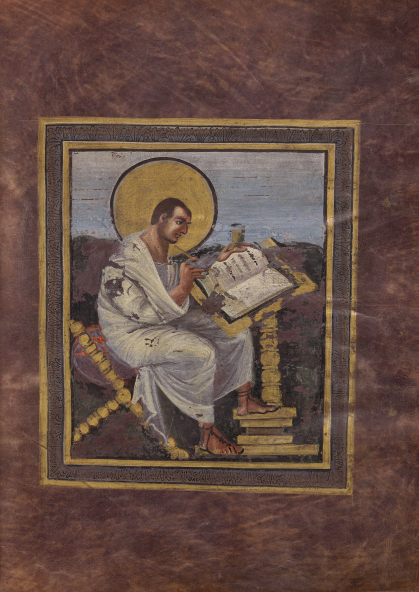

The artists of the Coronation Gospels were interested in the revival of classical styles, which effectively linked Charlemagne’s rule to that of the 4th-century ancient Roman emperor Constantine. The classical style is evident in the pose and clothing of Saint Matthew who recalls images of ancient Roman philosophers. Saint Matthew, folio 15 recto of the Coronation Gospels (Gospel Book of Charlemagne), from Aachen, Germany, c. 800–10, ink and tempera on vellum (Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

After the fall of Rome in the fifth century C.E., the locus of classical learning simply shifted North, to be expressed, for instance, in the reign of Charlemagne in the late eight and early ninth centuries. Charlemagne considered himself a Holy Roman Emperor, even though he had started as Frankish chieftain.

Still, the term Renaissance is best reserved for Italy, the place for which it was invented by scholars. The term “Northern Renaissance,” with its Italo-centric tilt, is problematic because it makes the independent flourishing of Northern art seem like a footnote to Italy. However, because art historians share a general understanding of what it means, “Northern Renaissance” is a convenient shorthand for the flowering of Northern art that occurred while the Renaissance was happening in Italy.

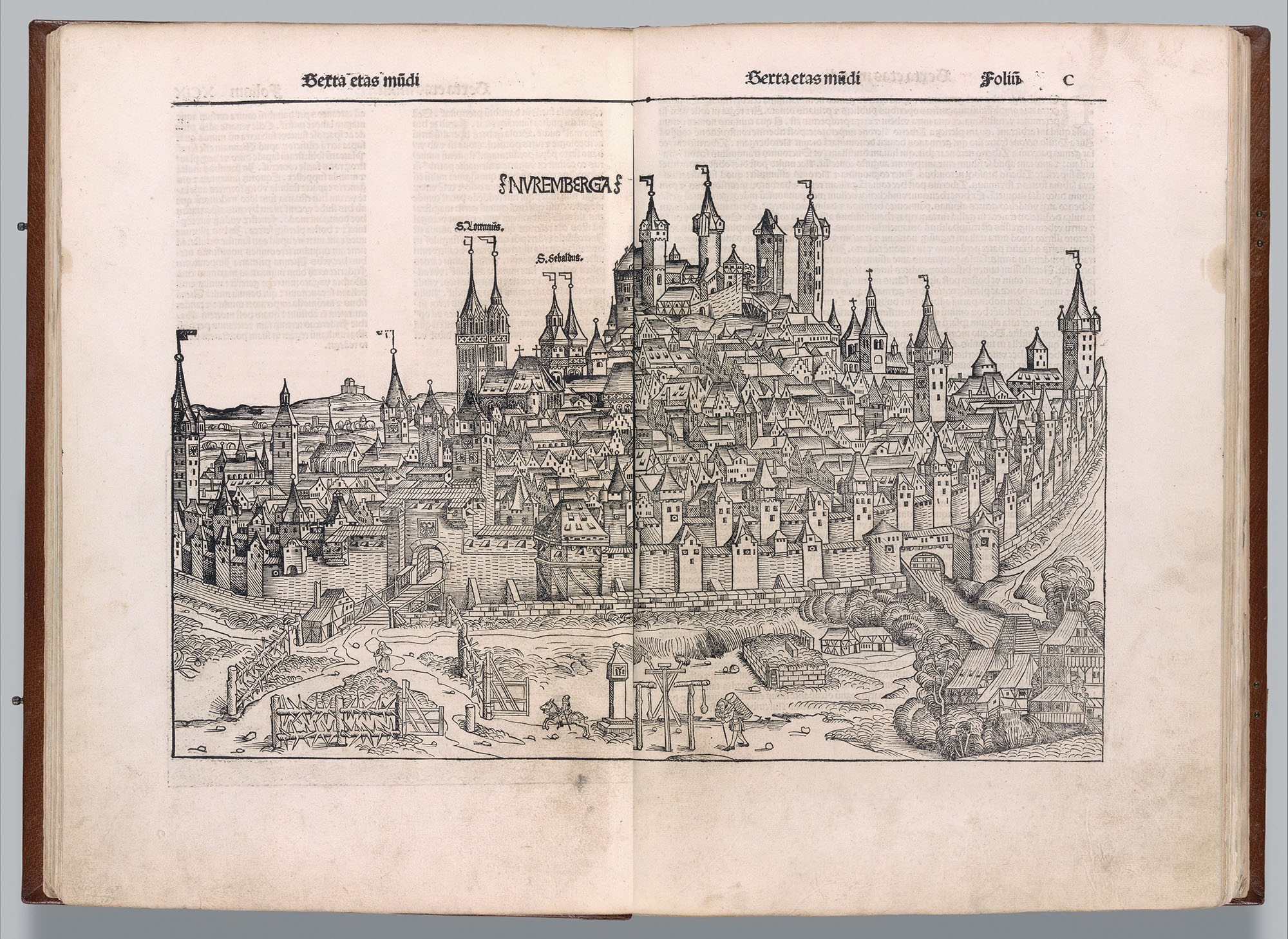

Michael Wolgemut, German, about 1435–1519, “View of the City of Nuremberg,” in The Nuremberg Chronicle, Nuremburg: Anton Koberger, 1493 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Simple chronological and geographical designators, such as “fifteenth-century Bruges” or “sixteenth-century Nuremberg” would be more precise, albeit wordier and less encompassing, and may be more useful when discussing specific artists or objects. With these provisos in mind, the term Northern Renaissance is still useful, even if it is imperfect.

Renaissance or Early Modern?

Scholars have debated why the Renaissance happened, when it started, when it ended, whom it affected, and whether or not “Renaissance” is a useful term to describe any of the diverse events of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries anywhere in Europe.

Some scholars use the term “Early Modern” to describe the broader changes in culture at the end of the Middle Ages. Though this term is also flawed and imprecise, it is more inclusive and indicates the role the era played in the foundation of the modern and contemporary world with practices such as international trade, colonialism, the continuing shift from agrarian to urban economies, and the exponentially expanded communication made possible through the invention of the printing press.

Object makers (artists)

Before and even into the Early Modern period, artists were trained craftspeople who worked skillfully but anonymously in workshops under the authority of a trained master. In the Early Modern era, we see the construction of the idea of a person as a discrete individual, rather than primarily as a member of a social or professional class. This idea is the basis for our familiar stereotype of the artist as a unique creator of expressive and deeply personal works of art, one we often associate with Italian renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Raphael.

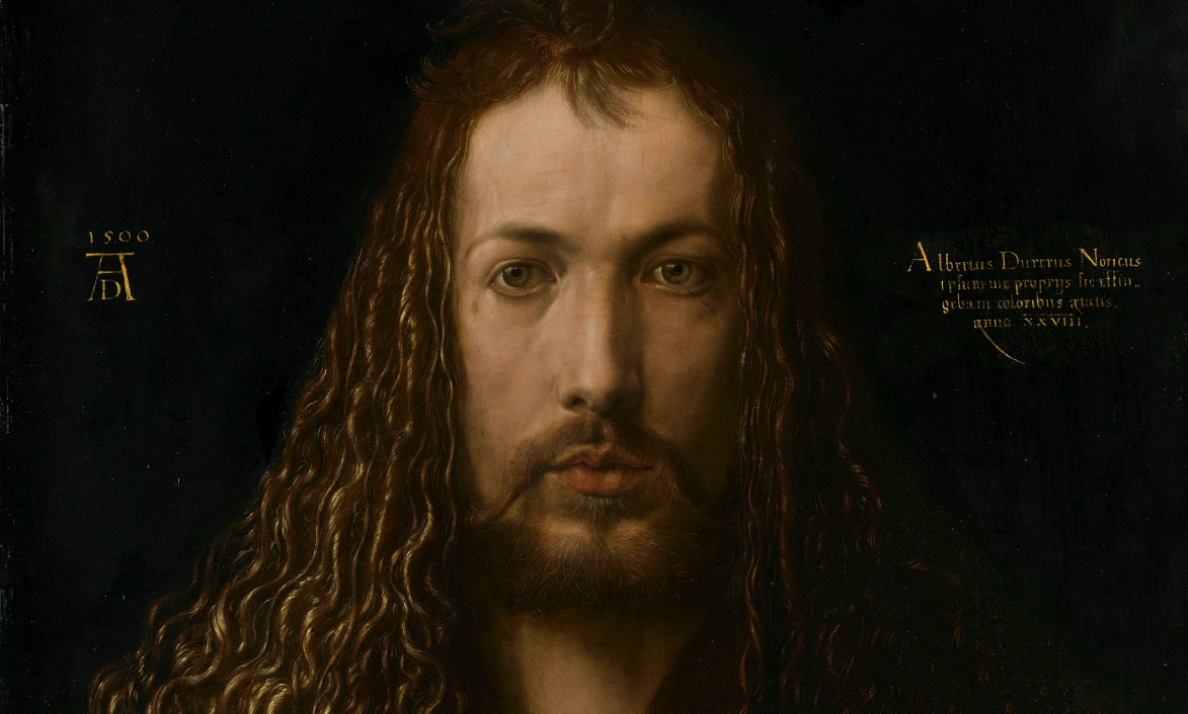

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I,1514, engraving, 24 x 18.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This idea flourished in the North as well. Albrecht Dürer admired and aspired to the rock-star status of Italian artists. The surpassing verisimilitude of Jan van Eyck’s oil paintings and the pathos of Rogier van der Weyden asserted the individuality of Northern artists independent of an interest in antiquity. For instance, today we talk about works of art as “a Michelangelo”, “a Raphael” or “a Dürer”. The dominance of artistic personality marks a shift away from the anonymity of the medieval craftsperson.

Watch videos and read essays about object makers

The role of the workshop in late medieval and early modern northern Europe: an introduction

Read Now >

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia: In this psychological self-portrait, Dürer captures an imagination paralyzed by inertia.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Oil paint

One of the most important innovations in the Northern Renaissance was the effective use of oil paint. Though Jan van Eyck did not invent oil paint, he used it more effectively than artists before his time. Oil allowed artists to paint in layers or glazes that convincingly mimicked the appearance of textures.

Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London)

Skin, hair, cloth, foodstuffs, metals, and fabrics glowed with an uncanny-seeming replication of visual experience. Imagine how astonishing the details of the Ghent Altarpiece or the Arnolfini Double Portrait may have appeared to people in the fifteenth century who had never seen a photograph!

Watch videos and read essays about oil paint

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait: This dense and detailed painting does not lack for symbols—or interpretations.

Read Now >

Jan Van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece: The inner panels are painted in the bold and dynamic naturalistic style for which the artist Jan van Eyck is justifiably famous.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Rogier van der Weyden, The Last Judgment, 1445–50, altarpiece, interior view (Hôtel-Dieu de Beaune)

Altarpieces

Oil paint was often used in Northern Europe to paint many-paneled paintings, known as polyptychs, which were placed behind the altar table as a backdrop to the performance of the Eucharist, the blessing of the bread and the wine. Such paintings adorning the altar are called altarpieces.

Workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), c. 1427–32, oil on oak panel, open 64.5 x 117.8 cm, central panel 64.1 x 63.2 cm, each wing 64.5 x 27.3 cm (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Altarpieces in the fifteenth century often emphasized the humanness of the Christian holy figures as much as, or even more than, their holiness. Saints, Christ, and the Virgin Mary bled and wept and celebrated just like the viewers who beheld them. Such humanizing bonded viewer and holy figure and granted viewers access to holiness via compassion. Empathic identification was the foundation of both small, private devotional objects that were kept in people’s homes as well, such as the Mérode Altarpiece and more monumental, public objects such as polyptychs.

Watch videos and read essays about altarpieces and oil paint

Workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece): Not only is the level of detail here astonishing, but these everyday objects embody religious symbols.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

Secular subjects in oil

Artists used oil paint and mimesis (seeming mimicry of reality) in secular subjects as well. Pieter Bruegel the Elder derived the subjects of his art from his responses to the world he lived in, and used oil paint to create a plausible illusion of reality.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, oil on canvas, 114 x 164 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

It is imperative, however, to remember that Bruegel’s hard-working or hard-partying peasants are not real people but caricatures and types. No picture can be an objective transcription of reality or a “scene of everyday life,” because all pictures are extrapolations, observations, and interpretations filtered through a person whose perceptions are in turn a product of history. Bruegel and other artists depicted peasants as stand-ins for human nature, and presented them as anonymous stereotypes carefully arranged in compositions intended to amuse but also flatter the beholder who was a member of a higher social class.

Watch videos and read an essay about secular subjects in oil

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Winter): What appears to be a candid snapshot of daily life is in fact a finely orchestrated and panoramic vision of the world.

Read Now >

Hans Holbein, The Ambassadors: The painting is filled with carefully rendered details—and an anamorphic skull.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Mechanical Reproducibility and Visual Propaganda

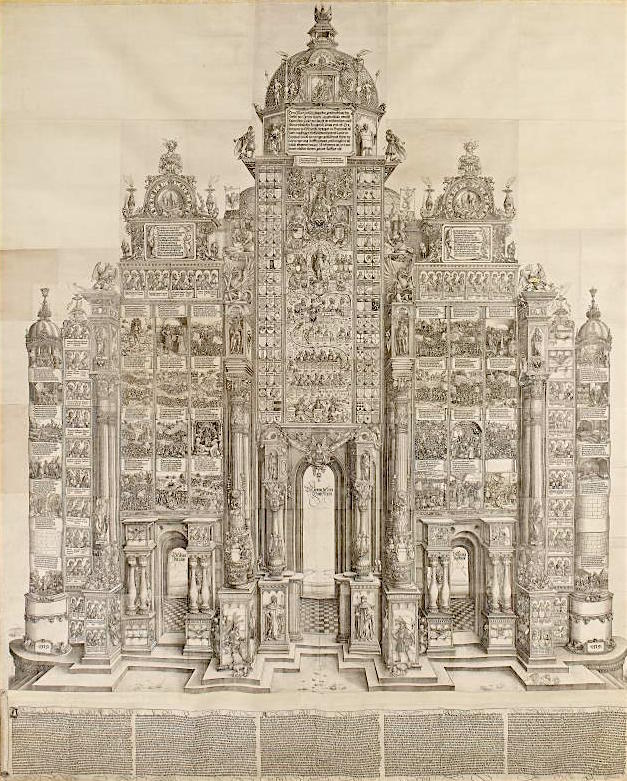

Albrecht Dürer and others, The Triumphal Arch, c. 1515, woodcut printed from 192 individual blocks, 357 x 295 cm, Germany © Trustees of the British Museum

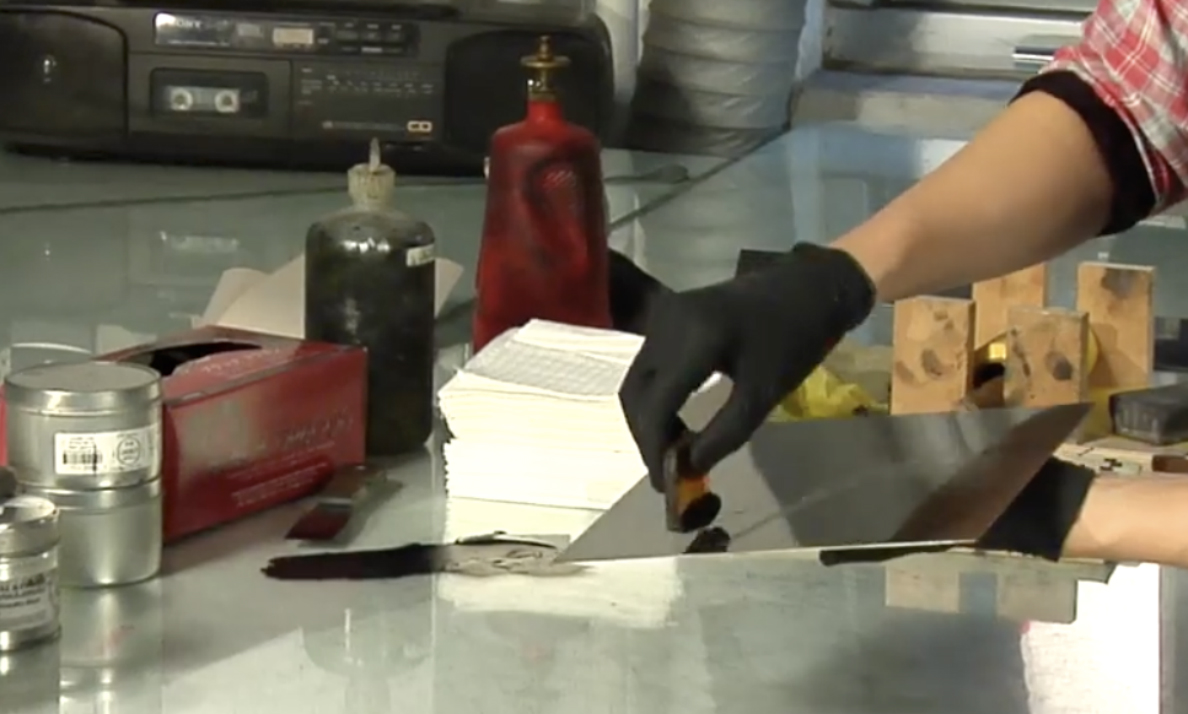

The development of mechanically reproducible media such as engravings and woodcuts was as life-changing as the advent of photography in the nineteenth century or digital media in the late twentieth. The Northern Renaissance is also the era when books were published with movable type rather than laboriously written by hand. Print technologies arrived in Europe late, as technologies moved from East Asia to Central Asia and finally Europe.

Watch videos and read essays about printmaking

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Dürer’s skill as a woodcut artist was his ability to conceive such complex and finely detailed images in the negative

Read Now >

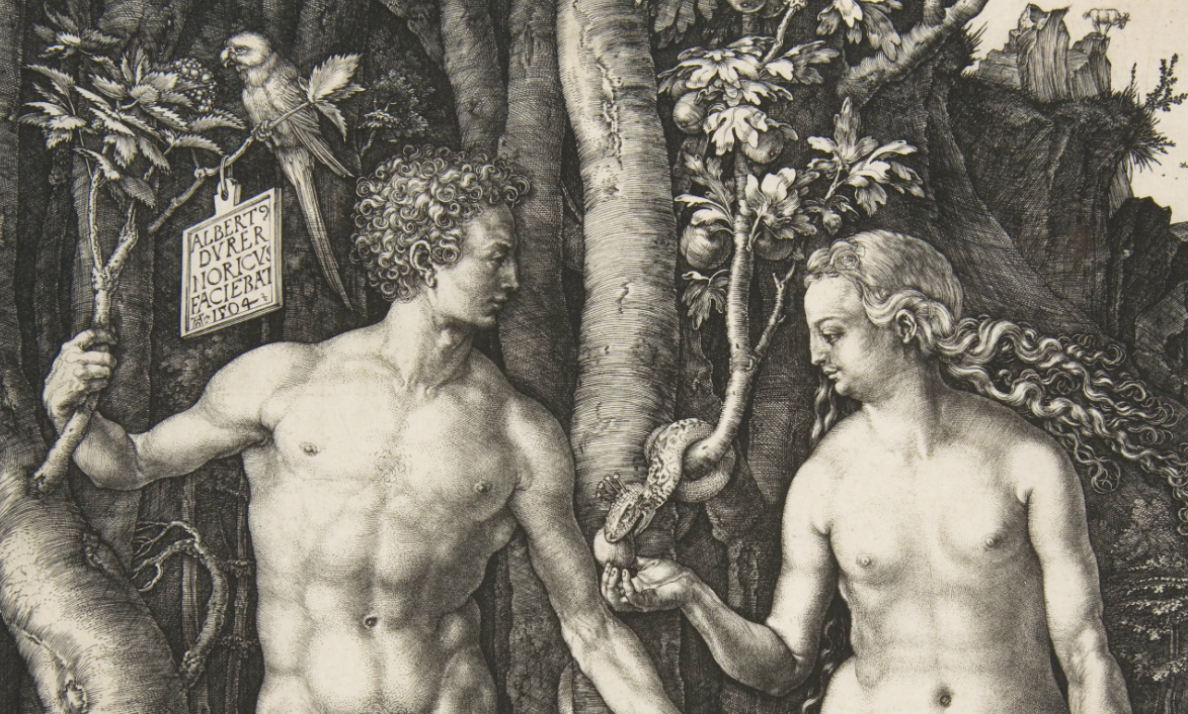

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve: The engraving of Adam and Eve of 1504 by the German renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer recasts this familiar story with nuances of meaning and artistic innovation.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Prints and Protestant Reformation

Printed pamphlets were arguably the engine of the Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517. Artists were employed to make Luther’s theology intelligible to broad swaths of viewers in prints as well as in paintings that were meant to function as conceptual blackboards, diagramming the new path to salvation independent of traditional Catholic rituals. Pictures such as Law and Gospel were constructed to avoid mimesis and emotion in favor of conceptual clarity— even though the intended clarity was not necessarily received as such.

Theodor de Bry, Christopher Columbus arrives in America, 1594, etching and text in letterpress, 18.6 c 19.6 cm (Rijksmuseum)

The impact of the Reformation was felt around the globe. As the Catholic Church lost wealth and members, it turned to the Americas in search of wealth and converts. The founding narrative of the United States reaches back to the arrival of the pilgrims in 1620 or even to the year before, when the first shipment of enslaved peoples from Africa arrived, even though Jamestown was founded earlier, in 1607. The pilgrims who sailed on the Mayflower were themselves radical Protestants who believed the Church of England was not pure enough.

Happily, Albrecht Dürer offers a refreshing alternative to colonialism. His response to an exhibition of Mexica (Aztec) objects when he travelled to the Low Countries in 1520 is telling.

Dürer, in a letter dated 27 August 1520

All the days of my life I have seen nothing that rejoiced my heart so much as these things, for I saw amongst them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle Ingenia of men in foreign lands. Indeed I cannot express all that I thought there.

Quoted from Wolfgang Stechow, Northern Renaissance Art, 1400–1600: Sources and Documents (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1989) pp. 100–01.

Watch videos and read essays about the Protestant Reformation and its effects

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Law and Gospel (Law and Grace): The single most influential image of the Lutheran Reformation.

Read Now >

Inventing “America” for Europe: Theodore de Bry’s engravings affirm and assert a sense of European superiority.

Read Now >

Theodor de Bry, “Their sitting at meate”: De Bry’s print presented an English colony as chock full of good things to eat and commodities to sell.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Understanding Northern art on its own terms

Albrecht Dürer traveled to Venice twice and returned to Germany enchanted by what he learned about Italian art. Pieter Bruegel the Elder traveled across the Alps as far south as Naples. Dürer, Bruegel, and other artists learned from the triumphs of Italian art and the rejuvenated Italian interest in antiquity. But the flourishing of print media, oil painting, and religious upheaval that characterized the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century are more important for understanding Northern art on its own terms.

Oil paintings conveyed a granular verisimilitude unparalleled in other media. Manuscripts (literally, hand-written) gave way to printed books. Mechanically reproducible media created an encompassing visual culture shared across geographical limits. Artists achieved a social status equal to their patrons. And the Reformation questioned the very essence of art, in some cases rejecting religious art entirely. Whatever vocabulary we may have at our disposal to describe the art and culture of Northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the surviving visual record testifies to the magnitude of change.

Key questions to guide your reading

Why do some scholars prefer the term “Early Modern” to “Renaissance”?

What role does mimesis play in Northern Renaissance oil painting?

What role did print media play in the advancement of the Protestant Reformation?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhy do some scholars prefer the term “Early Modern” to “Renaissance”?

What role does mimesis play in Northern Renaissance oil painting?

What role did print media play in the advancement of the Protestant Reformation?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Renaissance

Early Modern

Polyptych

Altarpiece

Oil paint

Mimesis

Engraving

Woodcut

Martin Luther

Protestant Reformation

Calvinism