Michael Pacher, Sankt Wolfgang Altarpiece, 1471-81, polychrome pine, linden, gilding, oil, over 40 feet high and more than 20 feet wide (Parish Church, Sankt Wolfgang, Austria)

The altar and the sacrament of the Eucharist

Every architectural space has a gravitational center, one that may be spatial or symbolic or both; for the medieval church, the altar fulfilled that role. This essay will explore what transpired at the altar during this period as well as its decoration, which was intended to edify and illuminate the worshippers gathered in the church.

The Christian religion centers upon Jesus Christ, who is believed to be the incarnation of the son of God born to the Virgin Mary.

During his ministry, Christ performed miracles and attracted a large following, which ultimately led to his persecution and crucifixion by the Romans. Upon his death, he was resurrected, promising redemption for humankind at the end of time.

The mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection are symbolically recreated during the Mass (the central act of worship) with the celebration of the Eucharist — a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice where bread and wine wielded by the priest miraculously embodies the body and blood of Jesus Christ, the Christian Savior.

Rogier van der Weyden, Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, 1445–50, oil on panel, 200 cm × 223 cm (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp)

Detail of the Eucharist, Rogier van der Weyden, Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, 1445-50 (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp)

The altar came to symbolize the tomb of Christ. It became the stage for the sacrament of the Eucharist, and gradually over the course of the Early Christian period began to be ornamented by a cross, candles, a cloth (representing the shroud that covered the body of Christ), and eventually, an altarpiece (a work of art set above and behind an altar).

In Rogier van der Weyden’s Altarpiece of the Seven Sacraments, one sees Christ’s sacrifice and the contemporary celebration of the Mass joined. The Crucifixion of Christ is in the foreground of the central panel of the triptych with St. John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross, while directly behind, a priest celebrates the Eucharist before a decorated altarpiece upon an altar.

Though altarpieces were not necessary for the Mass, they became a standard feature of altars throughout Europe from the thirteenth century, if not earlier. One of the factors that may have influenced the creation of altarpieces at that time was the shift from a more cube-shaped altar to a wider format, a change that invited the display of works of art upon the rectangular altar table.

Though the shape and medium of the altarpiece varied from country to country, the sensual experience of viewing it during the medieval period did not: chanting, the ringing of bells, burning candles, wafting incense, the mesmerizing sound of the incantation of the liturgy, and the sight of the colorful, carved story of Christ’s last days on earth and his resurrection would have stimulated all the senses of the worshipers. In a way, to see an altarpiece was to touch it—faith was experiential in that the boundaries between the five senses were not so rigorously drawn in the Middle Ages. For example, worshipers were expected to visually consume the Host (the bread symbolizing Christ’s body) during Mass, as full communion was reserved for Easter only.

Saints and relics

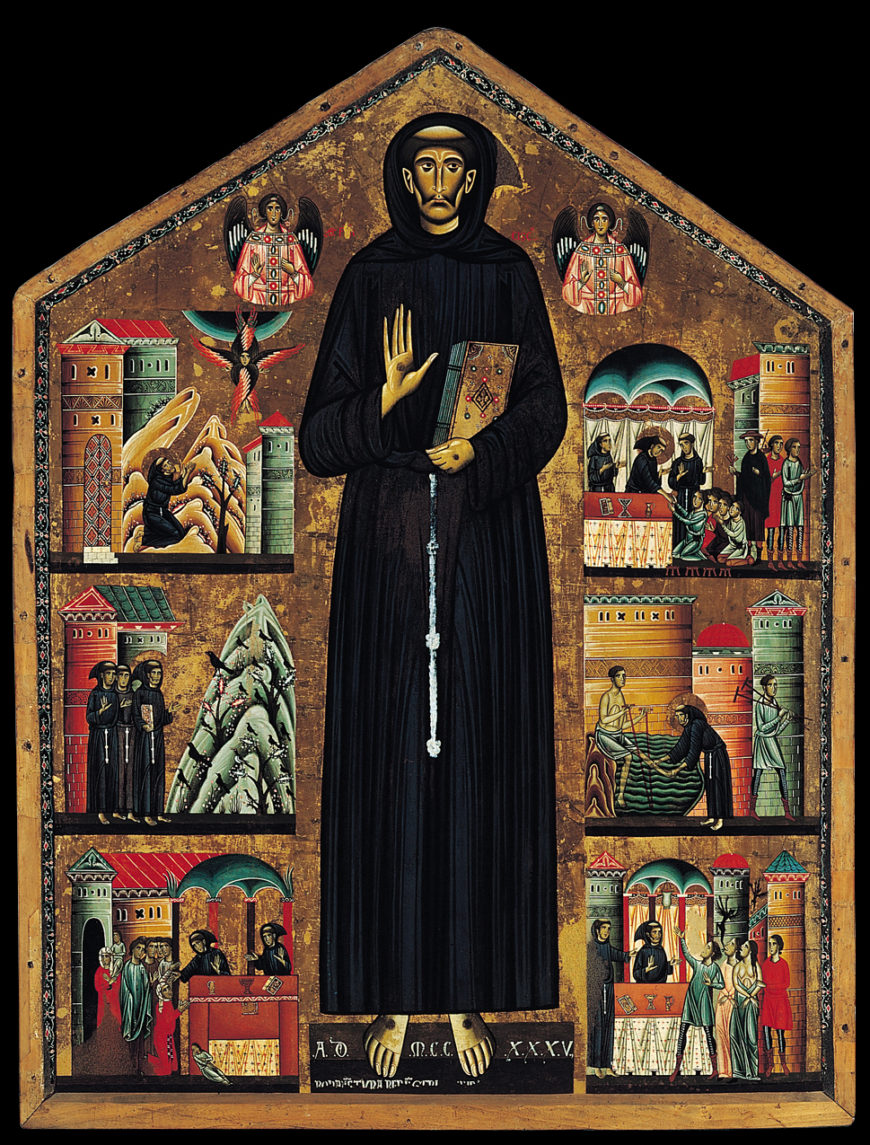

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, St. Francis of Assisi, c. 1235, tempera on wood (Church of San Francesco, Pescia)

Since the fifth century, saints’ relics (fragments of venerated holy persons) were embedded in the altar, so it is not surprising that altarpieces were often dedicated to saints and the miracles they performed. Italy in particular favored portraits of saints flanked by scenes from their lives, as seen, for example, in the image of St. Francis of Assisi by Bonaventura Berlinghieri in the Church of San Francesco in Pescia.

The Virgin Mary and the Incarnation of Christ were also frequently portrayed, though the Passion of Christ (and his resurrection) most frequently provided the backdrop for the mystery of Transubstantiation celebrated on the altar. The image could be painted or sculpted out of wood, metal, stone, or marble; relief sculpture was typically painted in bright colors and often gilded.

Germany, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia were most often associated with polyptychs (many-paneled works) that have several stages of closing and opening, in which a hierarchy of different media from painting to sculpture engaged the worshiper in a dance of concealment and revelation that culminated in a vision of the divine.

Rhenish Master, Altenberger Altar, c. 1330 (wings are in the collection of the Städel Museum, Frankfurt)

For example, the altarpiece from Altenberg contained a statue of the Virgin and Christ Child which was flanked by double-hinged wings that were opened in stages so that the first opening revealed painted panels of the Annunciation, Nativity, Death and Coronation of the Virgin (image above). The second opening disclosed the Visitation, Adoration of the Magi, and the patron saints of the Altenberg cloister, Michael and Elizabeth of Hungary. When the wings were fully closed, the Madonna and Child were hidden and painted scenes from the Passion were visible.

Variations

Rood screen of St. Andrew Church, Cherry Hinton, England (photo: Oxfordian Kissuth, CC BY-SA 3.0)

English parish churches had a predilection for rood screens, which were a type of carved barrier separating the nave (the main, central space of the church) from the chancel. Altarpieces carved out of alabaster became common in fourteenth-century England, featuring scenes from the life of Christ; these were often imported by other European countries.

The abbey of St.-Denis in France boasted a series of rectangular stone altarpieces that featured the lives of saints interwoven with the most important episodes of Christ’s life and death. For example, the life of St. Eustache unfolds to either side of the Crucifixion on one of the altarpieces, the latter of which participated in the liturgical activities of the church and often reflected the stained-glass subject matter of the individual chapels in which they were found.

Gothic beauty

The altarpiece of the Church of St. Martin, Ambierle, 1466 (photo: D Villafruela, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Detail of a donor with St. John the Baptist, Altarpiece of the Church of St. Martin, (photo: D Villafruela, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the later medieval period in France (15th–16th centuries), elaborate polyptychs with spiky pinnacles and late Gothic tracery formed the backdrop for densely populated narratives of the Passion and resurrection of Christ. In the seven-paneled altarpiece from the church of St.-Martin in Ambierle, the painted outer wings represent the patrons with their respective patron saints and above, the Annunciation to the Virgin by the archangel Gabriel of the birth of Christ. On the outer sides of these wings, painted in grisaille are the donors’ coats of arms.

Turrets (towers) crowned by triangular gables and divided by vertical pinnacles with spiky crockets create the framework of the polychromed and gilded wood carving of the inner three panels that house the story of Christ’s torture and triumph over death against tracery patterns that mimic stained glass windows found in Gothic churches.

The altarpiece of the Church of St. Martin, detail of the Passion (photo: D Villafruela, CC BY-SA 3.0)

To the left, one finds the Betrayal of Christ, the Flagellation, and the Crowning with the Crown of Thorns — scenes that led up to the death of Christ. The Crucifixion occupies the elevated central portion of the altarpiece, and the Descent from the Cross, the Entombment, and Resurrection are represented on the right side of the altarpiece.

There is an immediacy to the treatment of the narrative that invites the worshiper’s immersion in the story: anecdotal detail abounds, the small scale and large number of the figures encourage the eye to consume and possess what it sees in a fashion similar to a child’s absorption before a dollhouse. The scenes on the altarpiece are made imminently accessible by the use of contemporary garb, highly detailed architectural settings, and exaggerated gestures and facial expressions.

One feels compelled to enter into the drama of the story in a visceral way—feeling the sorrow of the Virgin as she swoons at her son’s death. This palpable quality of empathy that propels the viewer into the Passion of Christ makes the historical past fall away: we experience the pathos of Christ’s death in the present moment.

According to medieval theories of vision, memory was a physical process based on embodied visions. According to one twelfth-century thinker, they imprinted themselves upon the eyes of the heart. The altarpiece guided the faithful to a state of mind conducive to prayer, promoted communication with the saints, and served as a mnemonic device for meditation, and could even assist in achieving communion with the divine.

Chalice, mid-15th century, possibly from Hungary (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The altar had evolved into a table that was alive with color, often with precious stones, with relics, the chalice (which held the wine) and paten (which held the Host) consecrated to the blood and body of Christ, and finally, a carved and/or painted retable: this was the spectacle of the holy.

Paten, c. 1230-50, German (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

As Jean-Claude Schmitt put it:

this was an ensemble of sacred objects, engaged in a dialectic movement of revealing and concealing that encouraged individual piety and collective adherence to the mystery of the ritual.J.-C. Schmitt , “Les reliques et les images,” in Les reliques: Objets, cultes, symbols (Turnhout: 1999)

The story embodied on the altarpiece offered an object lesson in the human suffering experienced by Christ. The worshiper’s immersion in the death and resurrection of Christ was also an engagement with the tenets of Christianity, poignantly transcribed upon the sculpted, polychromed altarpieces.

Additional resources

Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, trans. Edmond Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Paul Binski, “The 13th-Century English Altarpiece,” in Norwegian Medieval Altar Frontals and Related Materials. Institutum Romanum Norvegiae, Acta ad archaeologiam et atrium historiam pertinentia 11, pp. 47–57 (Rome: Bretschneider, 1995).

Shirley Neilsen Blum, Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969).

Marco Ciatti, “The Typology, Meaning, and Use of Some Panel Paintings from the Duecento and Trecento,” in Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento, ed. Victor M. Schmidt, 15–29. Studies in the History of Art 61. Center for the Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. Symposium Papers 38 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002).

Donald L. Ehresmann, “Some Observations on the Role of Liturgy in the Early Winged Altarpiece,” Art Bulletin 64/3 (1982), pp. 359–69.

Julian Gardner, “Altars, Altarpieces, and Art History: Legislation and Usage,” in Italian Altarpieces 1250–1500: Function and Design, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, 5–39 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Peter Humfrey and Martin Kemp, eds., The Altarpiece in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Lynn F. Jacobs, “The Inverted ‘T’-Shape in Early Netherlandish Altarpieces: Studies in the Relation between Painting and Sculpture” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 54/1 (1991), pp. 33–65.

Lynn F. Jacobs, Early Netherlandish Carved Altarpieces, 1380–1550: Medieval Tastes and Mass Marketing (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Justin E.A. Kroesen and Victor M. Schmidt, eds., The Altar and its Environment, 1150–1400 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009).

Barbara G. Lane, The Altar and the Altarpiece: Sacramental Themes in Early Netherlandish Painting (New York: Harper & Row, 1984).

Henning Laugerud, “To See with the Eyes of the Soul, Memory and Visual Culture in Medieval Europe,” in ARV, Nordic Yearbook of Folklore Studies 66 (Uppsala: Swedish Science Press, 2010), pp. 43–68.

Éric Palazzo, “Art and the Senses: Art and Liturgy in the Middle Ages,” in A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages, ed. Richard Newhauser, pp. 175–94 (London, New Delhi, Sidney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014).

Donna L. Sadler, Touching the Passion—Seeing Late Medieval Altarpieces through the Eyes of Faith (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

Beth Williamson, “Altarpieces, Liturgy, and Devotion,” Speculum 79 (2004): 341–406.

Beth Williamson, “Sensory Experience in Medieval Devotion: Sound and Vision, Invisibility and Silence,” Speculum 88 1 (2013), pp. 1–43.

Kim Woods, “The Netherlandish Carved Altarpiece c. 1500: Type and Function,” in Humfrey and Kemp, The Altarpiece in the Renaissance, pp. 76–89.

Kim Woods, “Some Sixteenth-Century Antwerp Carved Wooden Altar-Pieces in England,” Burlington Magazine 141/1152 (1999), pp.144–55.