Taut skin, exposed ribs, a bleeding wound—this Christ suffered in both life and death. Medieval viewers took solace in his pain.

Röttgen Pietà, c. 1300–25, painted wood, 34 1/2 inches high (LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn). Speakers: Dr. Nancy Ross and Dr. Beth Harris

An emotional response

It is hard to look at the Röttgen Pietà and not feel something—perhaps revulsion, horror, or distaste. It is terrifying and the more you look at it, the more intriguing it becomes. This is part of the beauty and drama of Gothic art, which aimed to create an emotional response in medieval viewers.

Röttgen Pietà, c. 1300–25, painted wood, 34 1/2″ high (LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn) (photo: Ralf Heinz, with permission)

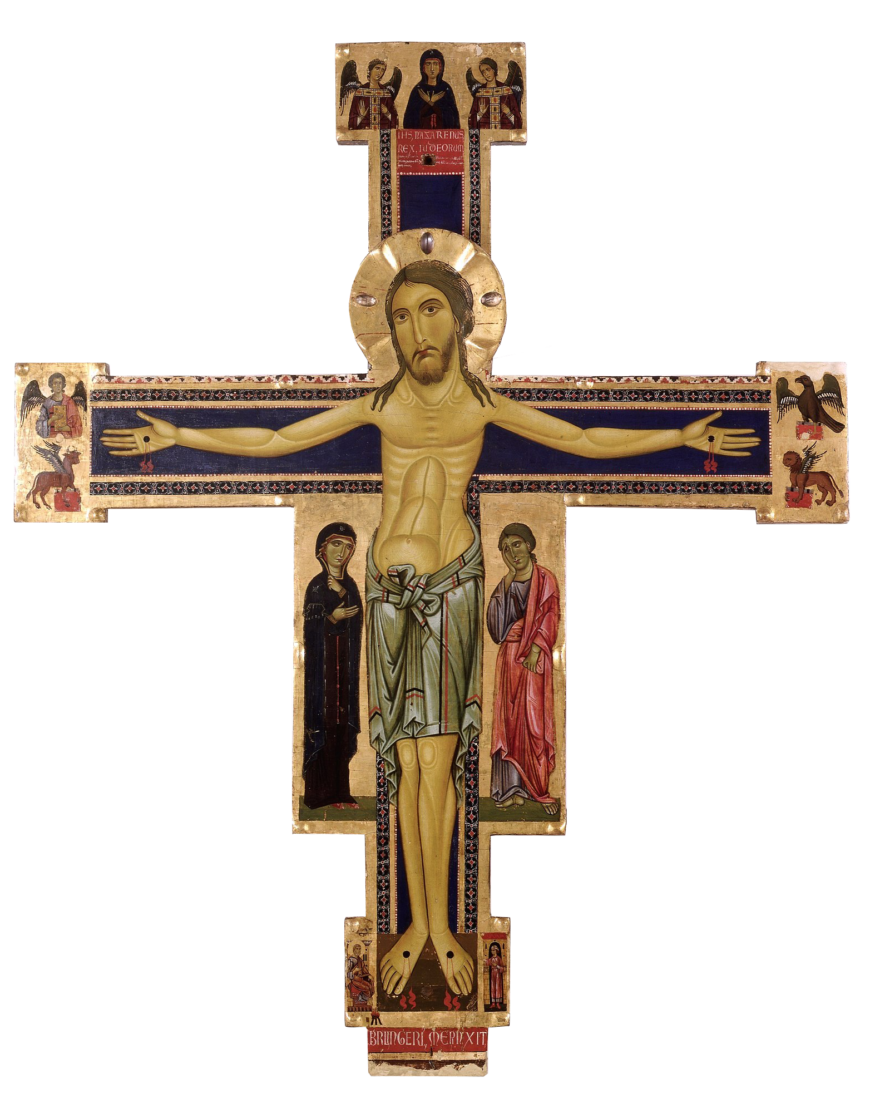

Earlier medieval representations of Christ focused on his divinity. In these works of art, Christ is on the cross, but never suffers. These types of crucifixion images are a type called Christus triumphans or the triumphant Christ. His divinity overcomes all human elements and so Christ stands proud and alert on the cross, immune to human suffering.

An example of a Christus triumphans (triumphant Christ), Berlinghiero Berlinghieri, Crucifix, c. 1220 (Museo nazionale di Villa Guinigi, Lucca)

Segna di Buonaventura, The Crucifixion, c. 1315, tempera on panel, 38.4 x 27 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Triumphant Christ / Patient Christ

In the later Middle Ages, a number of preachers and writers discussed a different type of Christ who suffered in the way that humans suffered. This was different from Catholic writers of earlier ages, who emphasized Christ’s divinity and distance from humanity.

Late medieval devotional writing (from the 13th–15th centuries) leaned toward mysticism and many of these writers had visions of Christ’s suffering. Francis of Assisi stressed Christ’s humanity and poverty. Several writers, such as St. Bonaventure, St. Bridget of Sweden, and St. Bernardino of Siena, imagined Mary’s thoughts as she held her dead son. It wasn’t long before artists began to visualize these new devotional trends. Crucifixion images influenced by this body of devotional literature are called Christus patiens, the patient Christ.

The effects of this new devotional style, which emphasized the humanity of Christ, quickly spread throughout western Europe through the rise of new religious orders (the Franciscans, for example) and the popularity of their preaching. It isn’t hard to see the appeal of the idea that God understands the pain and difficulty of being human. In the Röttgen Pietà, Christ clearly died from the horrific ordeal of crucifixion, but his skin is taut around his ribs, showing that he also led a life of hunger and suffering.

Pietà statues appeared in Germany in the late 1200s and were made in this region throughout the Middle Ages. Many examples of Pietàs survive today. Many of those that survive today are made of marble or stone but the Röttgen Pietà is made of wood and retains some of its original paint. The Röttgen Pietà is the most gruesome of these extant examples.

Pietà, c. 1420, polychromed poplar wood, 92 cm high, Austrian (Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Many of the other Pietàs also show a reclining dead Christ with three dimensional wounds and a skeletal abdomen. One of the unique elements of the Röttgen Pietà is Mary’s response to her dead son. She is youthful and draped in heavy robes like many of the other Marys, but her facial expression is different. In Catholic tradition, Mary had a special foreknowledge of the resurrection of Christ and so to her, Christ’s death is not only tragic. Images that reflect Mary’s divine knowledge show her at peace while holding her dead son. Mary in the Röttgen Pietà appears to be angry and confused. She doesn’t seem to know that her son will live again. She shows strong negative emotions that emphasize her humanity, just as the representation of Christ emphasizes his.

All of these Pietàs were devotional images and were intended as a focal point for contemplation and prayer. Even though the statues are horrific, the intent was to show that God and Mary, divine figures, were sympathetic to human suffering, and to the pain, and loss experienced by medieval viewers. By looking at the Röttgen Pietà, medieval viewers may have felt a closer personal connection to God by viewing this representation of death and pain.

Additional resources:

The Pietà at Harvard Art Museums

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re looking at the “Röttgen Pietà,” a devastating image that dates from the early 14th century. This is the late Gothic period, the latter part of the Middle Ages.

Dr. Nancy Ross: [0:15] Here we see a great example of the spirituality, the kind of mysticism that emerges in the later Middle Ages, and I think we really see that reflected here in this gruesomeness.

Dr. Harris: [0:28] It’s a very emotional image. Here we have Mary, the mother of God, holding her dead son on her lap, and so palpably dead, so gruesomely, so violent a death. Those gaping wounds in his hands and his feet, the gaping wound in his side, that three-dimensional blood that not only drips out, but explodes out of the body, even the sharpness of the crown of thorns. We can feel those thorns that not only emerge out toward us, but also went into Christ’s head. We see the painted blood dripping down his face.

Dr. Ross: [1:06] We call this the Pietà, but if we’re thinking of the narrative of the Passion of Christ, this is the Lamentation. This is when Mary laments the death of her dead son. The “Lamentation” from Giotto’s Arena Chapel is something that we often look at and refer to for Italian art of the similar period.

Dr. Harris: [1:23] This has no other figures around it. We’re just confronted with Mary and Christ.

Dr. Ross: [1:28] The storytelling element, that narrative element, is diminished here. The artist is asking us to focus on this particular interaction between Mary and her dead son, but something that I think is very interesting is Mary’s response.

[1:43] When I look at Mary here, I see that she’s got a furrowed brow. I see anger in that face. I see confusion. Normally, when we see representations of Mary in this late Gothic period, Mary is the queen of heaven. She’s this divine or semi-divine figure who has this foreknowledge that Christ’s death is going to be temporary, but when I look at Mary’s face here, I don’t see any of that foreknowledge.

Dr. Harris: [2:08] There’s this sense of, “How did the world go so awry that God made flesh was crucified?”

Dr. Ross: [2:15] What you’re describing there emphasizes Mary’s humanity, and earlier medieval representations show them as more distant and divine figures. This is a reflection of some changing ideas at the end of the Middle Ages.

[2:28] We would associate this with maybe Saint Francis of Assisi and with a few other medieval saints who are interested in mysticism, they’re interested in feeling their religion, and so they spend a lot of time contemplating the Crucifixion and the Passion to emotionally connect to those things, to enhance their religious belief.

[2:48] This statue and other Pietàs like it are really an outgrowth of this mystical idea, this idea that you can connect with God on a very emotional level.

Dr. Harris: [2:58] By stripping away those narrative elements, we’re left with this very stark image. We’re left with this concentration of emotion. It is interesting to compare this to Giotto’s “Madonna and Child” from about the same period, where we have an image of Mary as the queen of heaven, a figure who does not feel human emotions. She’s above that. She’s transcended that.

[3:21] Here, this emerging interest that we see in the Trecento, in the 1300s, in spiritual figures who are more like us and therefore we have empathy with them. We can see traces of color here. We see some of the red from the blood. It looks like green paint on the drapery, but we have to imagine back to these colors being much more vivid.

Dr. Ross: [3:43] We also see some damage in Mary’s head. We see some wormholes. This is a wooden sculpture, and we don’t have a tremendous amount of wooden sculpture that survives from the Middle Ages, so this is a really special example because it retains its paint.

[3:56] The paint is something that helps to bring the sculpture alive, and this sense of the imagery becoming alive is important to this mystical sense of visions in the later Middle Ages, where religious images were there to bring the moment alive in the mind of the viewer.

[4:13] All of that blood that we see dripping from the crown of thorns over Christ’s face, that’s really meant to intensify this sense that as you physically stand in front of the statue, it’s as though you’re seeing back through time to this event and then feeling the emotions.

Dr. Harris: [4:27] I also think about this on an altar, surrounded by a painted altarpiece, by other painted sculptures, by perhaps frescoes on the ceilings or walls of the church, by priests wearing beautiful liturgical vestments.

[4:43] We have to imagine this within a visually rich ecclesiastical environment and also imagine the sounds of the church, of prayers being said, of mass being said. When we imagine that whole environment, it’s easier to imagine that kind of visionary experience taking place.

Dr. Ross: [5:01] When I think of this in terms of an original location, a lot of these were present in German nunneries. I try to imagine the kind of emotional journey that the viewer would experience in spending time with this image, the initial shock and horror through to maybe feelings of empathy, and maybe even eventually feeling God suffered so badly he understands what I suffer.

[5:21] [music]