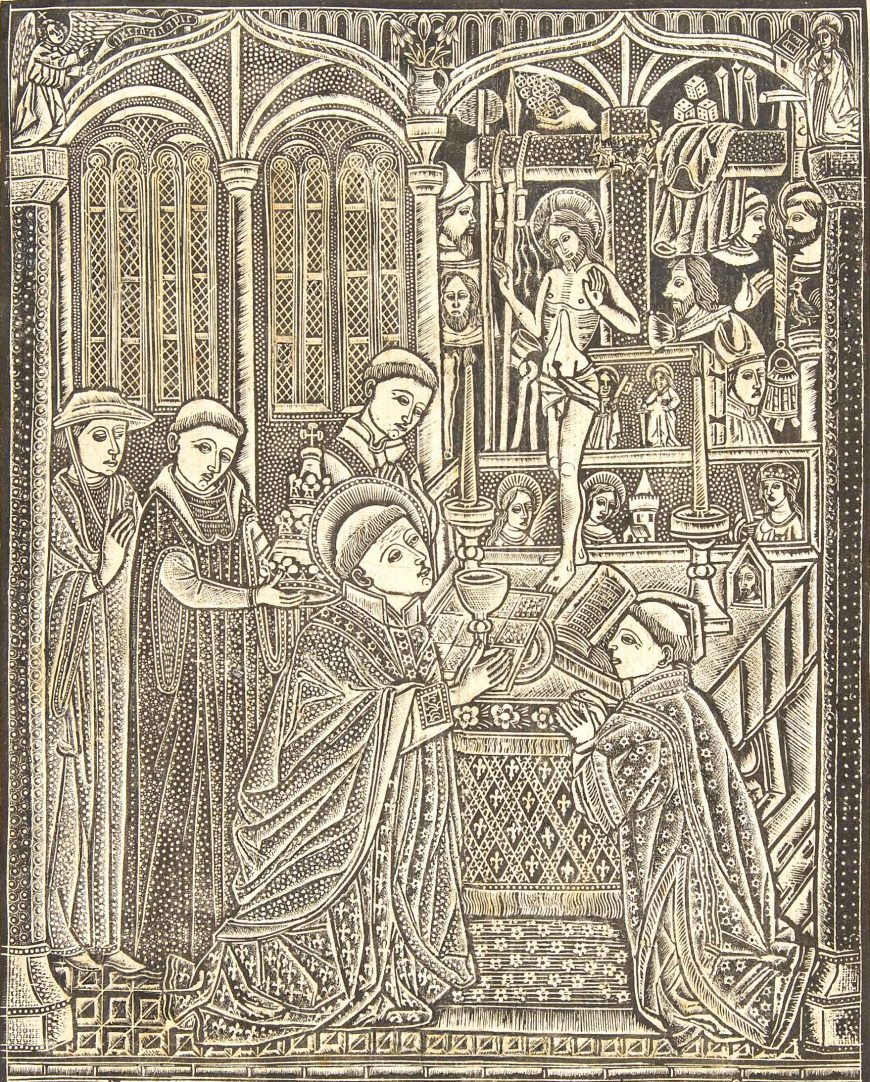

Priest receiving communion before altar (detail), Master of the Church Fathers’ Border, The Mass of Saint Gregory, late 15th century, metalcut with traces of hand-coloring; second state, 13 7/8 x 19 15/16 in (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The relationship between liturgy and architecture—between worship and the space in which it occurs—has a rich history in the Christian tradition. Its roots go back well before the emergence of Christianity to origins in Jewish worship. The term “liturgy” is from a Greek word that means “public service” or “work of the people” and has long been used to describe Christian worship. Today, churches are often described as either “liturgical” (e.g., Catholic, Episcopalian) or “non-liturgical” (e.g., Baptist, Pentecostal) depending on whether or not they use a scripted liturgy (such as the Book of Common Prayer). However, in its most basic sense, a liturgy is simply the order of events in a church service; therefore all churches are liturgical in the sense that all of their services have some kind of structure (welcome, opening prayer, hymn singing, sermon, closing prayer, dismissal, etc.).

View of the Dome of the Rock with western wall of Second Temple in the foreground, Jerusalem (photo: askii, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Jewish origins

As described in the Jewish Bible (Exodus 25–31), during their exile in the desert, the Israelites made sacrifices to God in the Tabernacle, which was a huge moveable tent. In a large outer court, they made sacrifices, and they burned incense in an inner chamber, dubbed the “Holy of Holies.” The Holy of Holies housed the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the Ten Commandments and the manna (the substance miraculously supplied as food to the Israelites in the wilderness), and was where God chose to reveal his presence. It wasn’t until King Solomon built the Temple in Jerusalem (possibly in the tenth century B.C.E.) that the Jews had a permanent place of worship. Although made of stone, the Temple had a similar layout as the Tabernacle. This Temple was destroyed in 586 B.C.E. and was replaced by the Second Temple (now the location of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem).

We don’t know much about the details of Temple liturgy, but worship included animal sacrifices, incense burning, chanting of the Psalms, blessings, and the making and eating of the “showbread” (bread placed on a specially dedicated table in the Temple as an offering to God).

Relief panel shwoing the Spoils of Jerusalem being brought into Rome, Arch of Titus, Rome, after 81 C.E., marble, 7 feet, 10 inches high (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

After the Roman commander (and later emperor) Titus destroyed the Second Temple in 70 C.E., the Jews were forced to worship only in their synagogues, which were—and remain today—halls for prayer and study (but not sacrifice). In addition to chanting psalms, prayers, and blessings, services in the synagogue also included the reading of scripture and teaching. This was reflected in the synagogue architecture, which included the bema, a platform from which men could read scripture and teach.

Early Christian worship

Many of the first Christians were Jews and so continued and reinterpreted many practices from the Temple and synagogue. We know from early Christian texts, such as the writings of Tertullian, Irenaeus of Lyons, and Justin Martyr, and the Didache (a first or second century text of possible Syrian origins) and the New Testament book of Hebrews that early Christian worship included some type of creedal statement, hymns, prayers, the reading of the Septuagint (the Hebrew Bible translated into Greek), teaching, meals, and baptism.

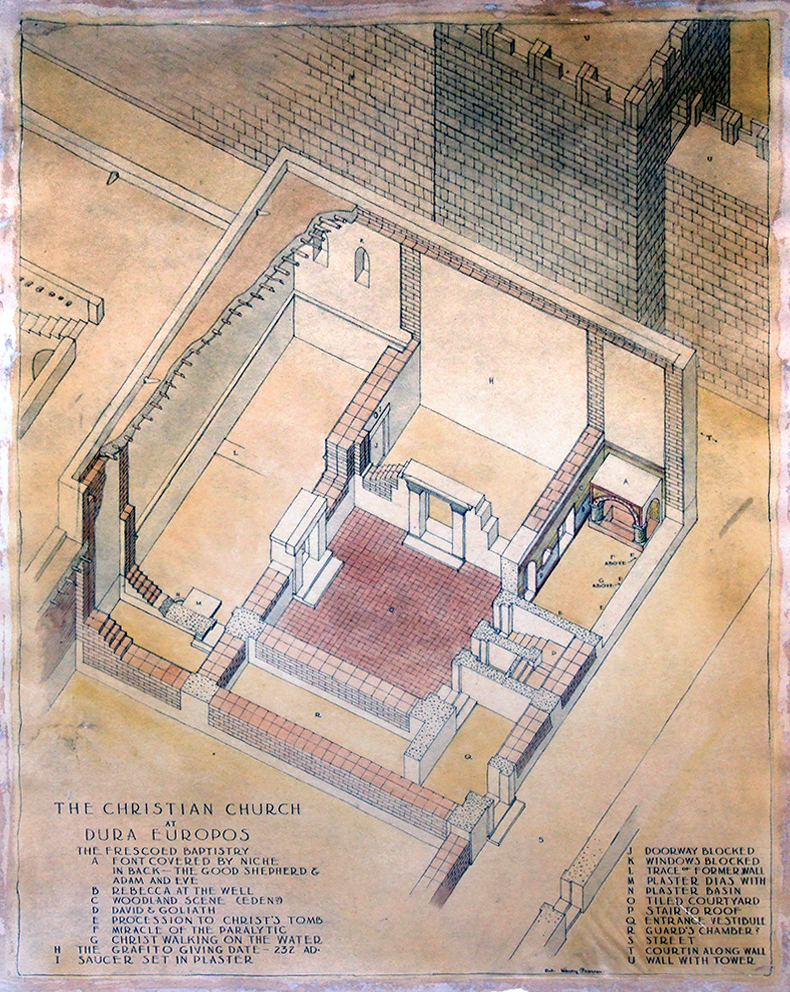

Isometric rendering of the Christian building at Dura-Europos (c. 240 C.E.), by Henry Pearson, 1932–34 (Yale University Art Gallery)

Before the year 313 C.E., when the emperor Constantine legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan, Christian worship occurred in homes, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. One of the earliest existing churches (dating to about 254 C.E.) is found at Dura-Europos, a Roman outpost in Syria. This small church had been converted from a typical Roman home, which had a square layout with a courtyard at its center. The church members apparently knocked down one of the walls to create a larger hall for teaching and the celebration of the eucharist (for Catholics, the miraculous transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ). One of the rooms was also turned into a baptistery, which contains some of the earliest surviving Christian frescoes.

View across central nave to one of two side aisles, Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (Basilica Nova), Roman Forum, c. 306–312 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Christian use of the Roman basilica

Not long after his conversion and subsequent legalization of Christianity, Constantine began an extensive building campaign to support his new state religion in major cities such as Rome, Jerusalem, and Constantinople. In looking for a structure to address the spatial needs of the developing Christian liturgy (such as increasing congregation size and more elaborate processions), he adapted the Roman basilica, which until that point had been used exclusively as a civic building, like the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine.

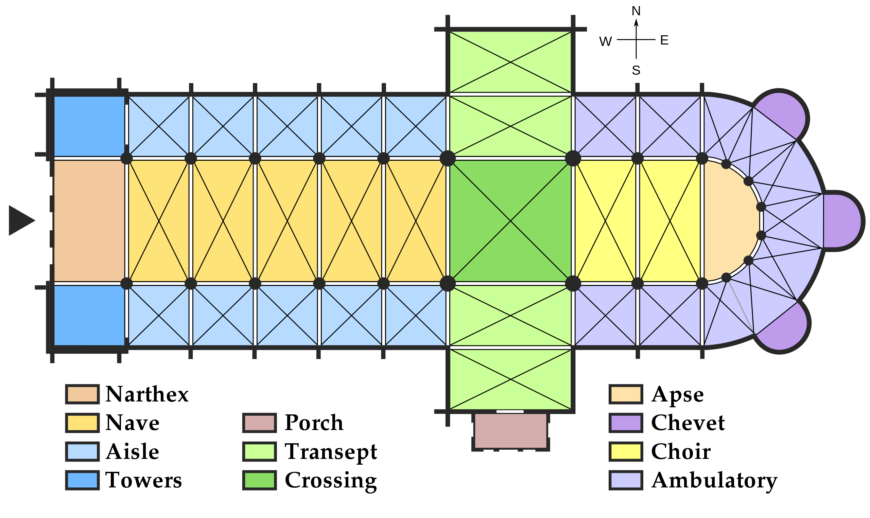

Roman basilicas were long rectangular buildings, often with a central nave (a wide, center aisle) and two side aisles. There was at least one semicircular apse, often at one end of the building, in which the magistrates sat and heard their cases. The basilica was in many ways the perfect building to adapt into a church because it did not have the pagan associations that Roman temples did and was large enough to accommodate the growing Christian population.

Exterior view of the apse, Basilica of Santa Sabina, c. 432 C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA)

Early Christian basilicas such as Santa Sabina and San Paolo fuori le Mura (St. Paul’s Outside the Walls) maintained the basic structure of the Roman basilica, but distinctly Christian elements were added. The bema was retained from the synagogue and continued to be used as the raised platform from which priests preached (by the late Middle Ages this was often attached to a pillar to one side of the central aisle of the nave). Many churches added the ambo, an even higher platform, accessed by stairs, from which the Gospel was read and sermons were preached—in which case the bema was reserved for the recitation of prayers and the reading of the Epistles or Old Testament. Another distinctly Christian architectural element was the transept, which was added near the apse-end of the building to form a cross-shape and provide additional space.

View down the nave towards the apse with altar, Basilica of Santa Sabina, c. 432 C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Most significant among the Christian additions to the basilica, and the central focus for the liturgy, was the altar upon which the eucharist was celebrated. Altars were located either right in front of or just inside of the apse (as in Santa Sabina)—that is, within the Christian equivalent of the Jewish Holy of Holies. Up until the Middle Ages, most altars were wooden table-like structures; they then transitioned into stone. In the early fifth century, the Church formally required the installation of saints’ relics (often bone fragments) in altars. This practice was based in part on the tradition of placing altars on top of martyrs’ tombs (like at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome) and the text of Revelation 6:9-10, which describes martyrs crying out for justice from under the altar in heaven. The three main areas of the church came to be ascribed with symbolic meaning: the narthex, or entry, was the world; the nave, or main hall, was the Kingdom of God; and the sanctuary, or altar area—like the Holy of Holies—was heaven.

Medieval church floor plan (diagram: Leonce49, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Medieval worship

The structures of both the liturgy and church architecture remained basically the same in the Middle Ages, but became increasingly complex and diverse as Christianity spread throughout the empire. We can think of the liturgy as the script and the church architecture as the stage upon which it was performed. The “actors” were the clergy of course, consisting of priests, deacons, and liturgical assistants, but the congregation also had an essential role. They not only participated in the call and response of prayers and hymns in the liturgy and walked in processions within and without the church walls, but they also practiced personal devotion during the celebration of liturgy. It was not uncommon for lay people to move about the building independent of the liturgy in order to pray or light candles at the smaller shrines in a church’s side chapels.

View down the nave to the altarpiece by Michael Pacher (1471–81), Parish Church, Saint Wolfgang, Austria (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As is still the case in modern churches, liturgy and architecture mutually influenced one another in the Middle Ages. The walls and floors of medieval churches were often covered with plaques and tombs dedicated to church members and saints, as well as images of Christ, Mary, saints, and angels. These images and memorials influenced the movements of the faithful, as they moved about the church interior to venerate their particular favorites. A shrine of a popular or historically important saint would receive more attention, perhaps in the form of donations, and thus would be embellished. Or if, for example, the bones of a saint or martyr were interred in a particular location of the church, others would seek to be buried as close as possible to that tomb, and so on. These are just a few of the many ways in which theology and devotional practice could influence the church environment and vice versa.

Chancel (9th century), Basilica of Santa Sabina, c. 432 C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There were also areas of the church that were off-limits for the laity (the non-clergy public), most notably the altar area. Initially the use of chancels, or waist-high walls, were used to separate the congregation from the altar for very practical reasons like keeping dogs away from the bread and the wine of the eucharist or retaining large crowds on major holidays. However, with time, these partitions were made higher and more ornate, peaking in the late Middle Ages when they often reached the ceiling of the church and completely obstructed the congregation’s view of the altar.

Relics and pilgrimage

Images and relics also influenced religious activity on a much larger scale beyond the walls of the church. Religious pilgrimage had been an important part of Christian devotion since the time of Constantine and his building campaign in the Holy Land and Constantinople (a pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place). Of course, not everyone was financially or physically able to make such a trek and in response, church architecture and religious objects (such as reliquaries) began to invoke elements of particular pilgrimage sites or recreate pilgrimages on a smaller scale. For example, architectural elements of Holy Land buildings such as the Church of the Holy Sepulcher were often referenced in the churches of Western Europe, or even explicitly invoked, as in the name of the basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (the basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem) in Rome. Relics of important saints were also used to refocus attention. For instance, the founding of a new political center (say, Charlemagne’s palace and chapel at Aachen) often entailed the relocation of relics to embody divine approval and authority and/or entice pilgrims and visitors.

Chapel of Wenceslas, 1344–64, Prague Cathedral (photo: DXR, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Beatus of Liébana, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 11th century, Vitr. 14.2, f. 253v (Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid)

Spiritual architecture

We should also note that, in a sense, the physical progression of the faithful from the nave of the church to the altar—if and when they participated in the eucharist—was itself a small-scale, local version of a pilgrimage, in which they moved from their present reality to the future promise of heaven. The spiritual understanding of the church and its architecture also impacted the actual design of medieval churches. Biblical passages such as Revelation 21:9-21, which describes a vision of an angel measuring the city of the Heavenly Jerusalem, inspired medieval Christians to ascribe spiritual significance to the dimensions and proportions of church architecture. Revelation 21:9-21 is illustrated, for example, in the eleventh-century manuscript of Beatus of Liébana’s Commentary on the Apocalypse, which depicts one angel holding a measuring rod in the city center as twelve angels stand at its twelve gates, visually becoming part of the architecture of the Heavenly Jerusalem. While, in a sense, all medieval churches were understood to be symbolic of the Heavenly Jerusalem, some invoked its imagery more literally, as found in the use of semiprecious stones (cf. Rev. 21:9,19) set into the dado (lower walls) of the chapels of St. Catherine and the Holy Cross at Karlstein, and the chapel of Wenceslas in the Prague Cathedral.

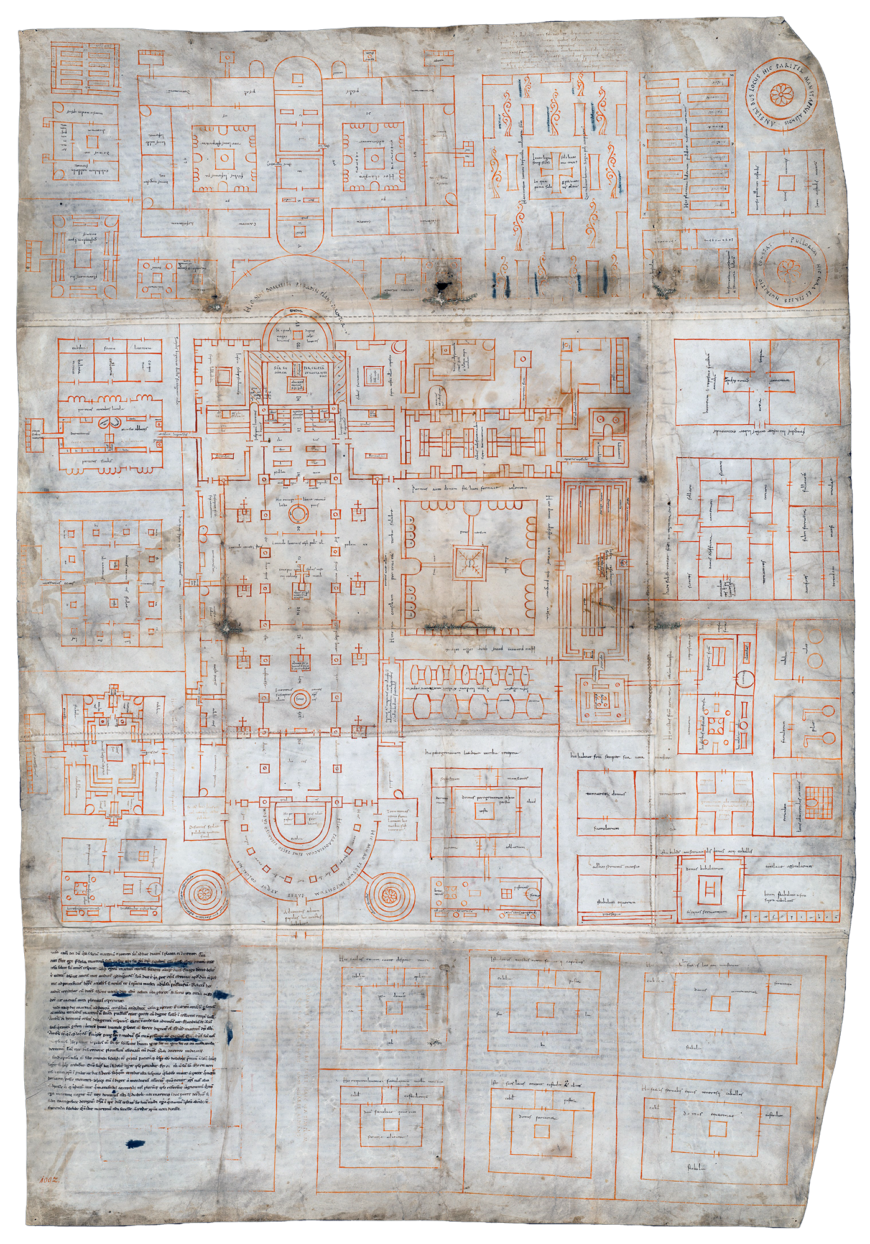

Plan of St. Gall, c. 820 C.E., parchment, Cod. Sang. 1092, 112 x 77.5 cm (Stiftsbibliothek Sankt Gallen, St. Gallen)

Another example of spiritual architecture is found in the monastic complex of the Plan of St. Gall, the exact purpose of which remains a matter of scholarly debate today. Christian monasticism dates back to the desert monks of the fourth century. The monks led lives of poverty, prayer, and asceticism which were formalized in several important guidebooks or “rules”; one of the most influential was the Rule of St. Benedict, which regulated the monks’ lives by hourly prayer and the celebration of the liturgy, or the “offices.” Something of this regulation is visible in the Plan of St. Gall, which depicts more than forty structures, including a church, a scriptorium (a place where monks who were scribes copied books), residence halls, and buildings for preparing and eating food. Grids and squares dominate the Plan’s buildings and gardens, creating a visual sense of order. Regardless of whether its elaborate schematic was intended for the construction of an actual building in the Carolingian empire, it seems that the Plan of St. Gall was meant to be a diagram of the ideal, spiritual monastery.

Mapping time

In short, while there was a broad range of experience and understanding of the church and its liturgy throughout Europe—from the peasant who attended rarely if ever, to the clergy who used and often commissioned buildings and furnishings, to the aristocrats who funded much of medieval monumental art and manuscripts, even to kings and the emperor himself—life in the Middle Ages was measured out by the liturgical calendar. Churches were focal points of the medieval landscape and their ceremonies and processions periodically mapped out the sacred even beyond the church walls.

Additional resources

Read a Reframing Art History textbook chapter on late medieval multimedia and devotion.

Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Dura-Europos from the Yale University Art Gallery.

Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Allan Doig, Liturgy and Architecture: From the Early Church to the Middle Ages (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008).

Thomas J. Doig and E. Ann Matter, eds., The Liturgy of the Medieval Church, 2nd ed. (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2005).

Richard Kieckhefer, Theology in Stone: Church Architecture from Byzantium to Berkeley (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Cyrille Vogel, Medieval Liturgy: An Introduction to the Sources, revised and translated by William G. Storey and Niels Krogh Rasmussen, (O.P. Washington, D.C.: The Pastoral Press, 1986).

James F. White, A Brief History of Christian Worship (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1993).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”ArchLit,”]