Wittenberg, 1725, engraving, 18 x 15 cm (State and University Library, Dresden)

A challenge to the Church in Rome

In art history, the 16th century sees the styles we call the High Renaissance followed by Mannerism, and—at the end of the century—the emergence of the Baroque style. Naturally, these styles are all shaped by historical forces, the most significant being the Protestant Reformation’s successful challenge to the spiritual and political power of the Church in Rome. For the history of art, this has particular significance since the use (and abuse) of images was the topic of debate. In fact, many images were attacked and destroyed during this period, a phenomenon called iconoclasm.

The Protestant Reformation

Today there are many types of Protestant Churches. For example, Baptist is currently the largest denomination in the United States but there are many dozens more. How did this happen? Where did they all begin? To understand the Protestant Reform movement, we need to go back in history to the early 16th century when there was only one church in Western Europe—what we would now call the Roman Catholic Church—under the leadership of the Pope in Rome. Today, we call this “Roman Catholic” because there are so many other types of churches (i.e. Methodist, Baptist, Lutheran, Calvinist, Anglican—you get the idea).

The Church and the state

So, if we go back to the year 1500, the Church (what we now call the Roman Catholic Church) was very powerful (politically and spiritually) in Western Europe (and in fact ruled over significant territory in Italy called the Papal States). But there were other political forces at work too. There was the Holy Roman Empire (largely made up of German speaking regions ruled by princes, dukes, and electors), the Italian city-states, England, as well as the increasingly unified nation states of France and Spain (among others). The power of the rulers of these areas had increased in the previous century and many were anxious to take the opportunity offered by the Reformation to weaken the power of the papacy (the office of the Pope) and increase their own power in relation to the Church in Rome and other rulers.

Keep in mind too, that for some time the Church had been seen as an institution plagued by internal power struggles (at one point in the late 1300s and 1400s church was ruled by three Popes simultaneously). Popes and cardinals often lived more like kings than spiritual leaders. Popes claimed temporal (political) as well as spiritual power. They commanded armies, made political alliances and enemies, and, sometimes, even waged war. Simony (the selling of Church offices) and nepotism (favoritism based on family relationships) were rampant. Clearly, if the Pope was concentrating on these worldly issues, there wasn’t as much time left for caring for the souls of the faithful. The corruption of the Church was well known, and several attempts had been made to reform the Church (notably by John Wyclif and Jan Hus), but none of these efforts successfully challenged Church practice until Martin Luther’s actions in the early 1500s.

Friedrich Drake, Door of Theses, Castle Church, Wittenberg, Germany, 1858, bronze (photo: public domain)

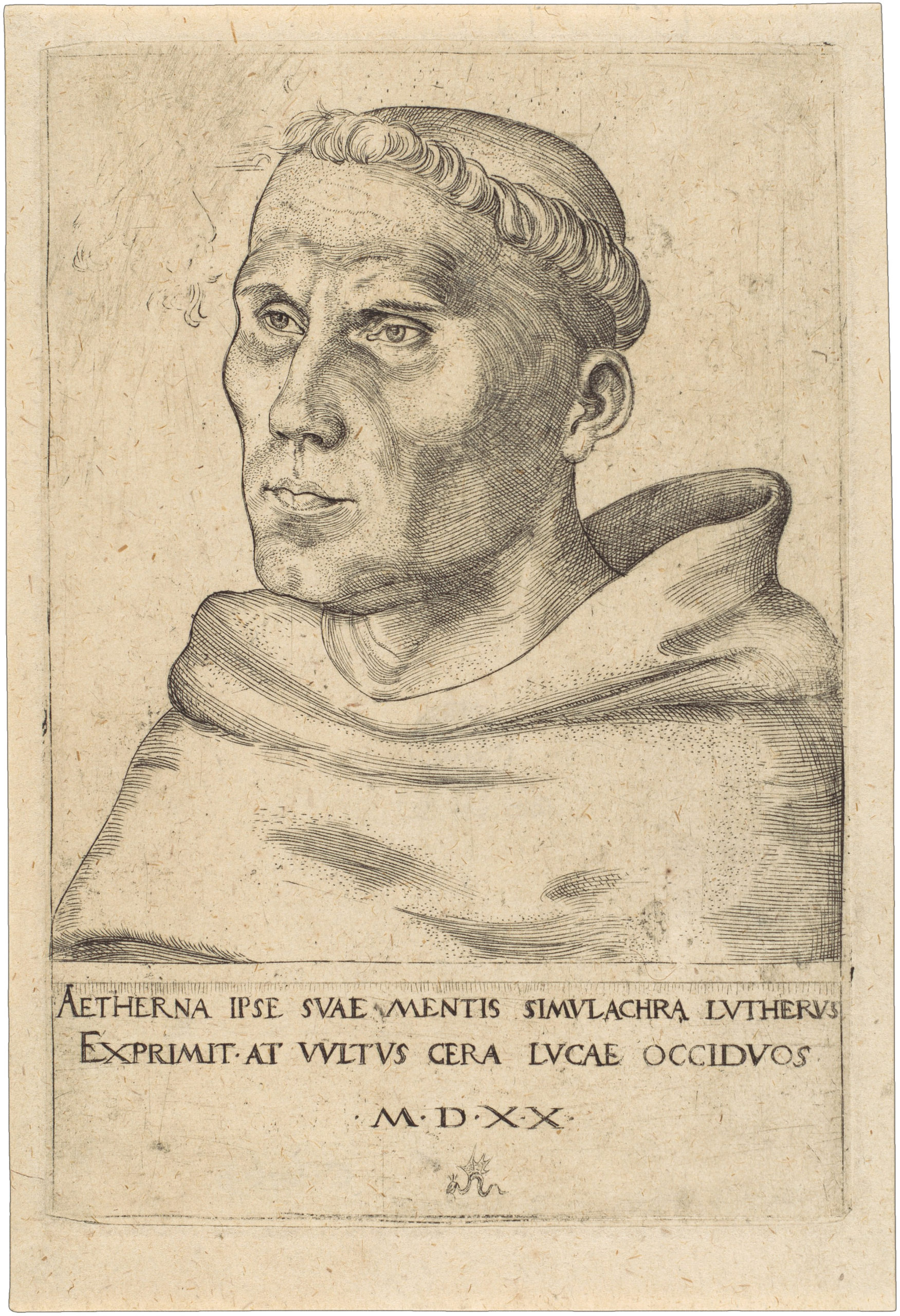

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk, 1520, engraving, 14.3 x 9.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German monk and Professor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg. Luther sparked the Reformation in 1517 by posting, at least according to tradition, his “95 Theses” on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. These theses were a list of statements that expressed Luther’s concerns about certain Church practices—largely the sale of indulgences, but they were based on Luther’s deeper concerns with Church doctrine. Before we go on, notice that the word Protestant contains the word “protest” and that reformation contains the word “reform”—this was an effort, at least at first, to protest some practices of the Catholic Church and to reform that Church.

Indulgences

The sale of indulgences was a practice where the Church acknowledged a donation or other charitable work with a piece of paper (an indulgence), that certified that your soul would enter heaven more quickly by reducing your time in purgatory. If you committed no serious sins that guaranteed your place in hell, and you died before repenting and atoning for all of your sins, then your soul went to purgatory—a kind of way-station where you finished atoning for your sins before being allowed to enter heaven.

Pope Leo X had granted indulgences to raise money for the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. These indulgences were being sold by Johann Tetzel not far from Wittenberg, where Luther was Professor of Theology. Luther was gravely concerned about the way in which getting into heaven was connected with a financial transaction. But the sale of indulgences was not Luther’s only disagreement with the institution of the Church.

Faith alone

Martin Luther was very devout and had experienced a spiritual crisis. He concluded that no matter how “good” he tried to be, no matter how he tried to stay away from sin, he still found himself having sinful thoughts. He was fearful that no matter how many good works he did, he could never do enough to earn his place in heaven (remember that, according to the Catholic Church, doing good works, for example commissioning works of art for the Church, helped one gain entrance to heaven). This was a profound recognition of the inescapable sinfulness of the human condition. After all, no matter how kind and good we try to be, we all find ourselves having thoughts which are unkind and sometimes much worse. Luther found a way out of this problem when he read St. Paul, who wrote “The just shall live by faith” (Romans 1:17). Luther understood this to mean that those who go to heaven (the just) will get there by faith alone—not by doing good works. In other words, God’s grace is something freely given to human beings, not something we can earn. For the Catholic Church, on the other hand, human beings, through good works, had some agency in their salvation.

Scripture alone

Luther (and other reformers) turned to the Bible as the only reliable source of instruction (as opposed to the teachings of the Church). The invention of the printing press in the middle of the 15th century (by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany) together with the translation of the Bible into the vernacular (the common languages of French, Italian, German, English, etc.) meant that it was possible for those that could read to learn directly from Bible without having to rely on a priest or other church officials. Before this time, the Bible was available in Latin, the ancient language of Rome spoken chiefly by the clergy. Before the printing press, books were handmade and extremely expensive. The invention of the printing press and the translation of the Bible into the vernacular meant that for the first time in history, the Bible was available to those outside of the Church. And now, a direct relationship to God, unmediated by the institution of the Catholic Church, was possible.

When Luther and other reformers looked to the words of the Bible (and there were efforts at improving the accuracy of these new translations based on early Greek manuscripts), they found that many of the practices and teachings of the Church about how we achieve salvation didn’t match Christ’s teaching. This included many of the sacraments, including Holy Communion (also known as the Eucharist). According to the Catholic Church, the miracle of Communion is transubstantiation—when the priest administers the bread and wine, they change (the prefix “trans” means to change) their substance into the body and blood of Christ. Luther denied that anything changed during Holy Communion. Luther thereby challenged one of the central sacraments of the Catholic Church, one of its central miracles, and thereby one of the ways that human beings can achieve grace with God, or salvation.

The Counter-Reformation

The Church initially ignored Martin Luther, but Luther’s ideas (and variations of them, including Calvinism) quickly spread throughout Europe. He was asked to recant (to disavow) his writings at the Diet of Worms (an unfortunate name for a council held by the Holy Roman Emperor in the German city of Worms). When Luther refused, he was excommunicated (in other words, expelled from the church). The Church’s response to the threat from Luther and others during this period is called the Counter-Reformation (“counter”—against).

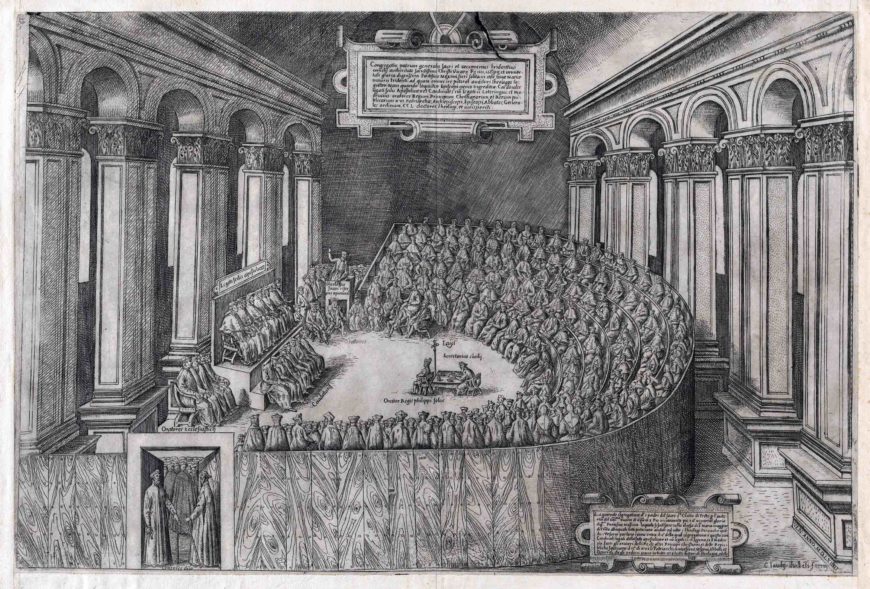

Council of Trent, 1565, in the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, etching and engraving, 33.5 x 49.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The Council of Trent

In 1545 the Church opened the Council of Trent to deal with the issues raised by Luther. The Council of Trent was an assembly of high officials in the Church who met (on and off for eighteen years) principally in the Northern Italian town of Trent for 25 sessions.

Selected Outcomes of the Council of Trent:

- The Council denied the Lutheran idea of justification by faith. They affirmed, in other words, their Doctrine of Merit, which allows human beings to redeem themselves through Good Works, and through the sacraments.

- They affirmed the existence of purgatory and the usefulness of prayer and indulgences in shortening a person’s stay in purgatory.

- They reaffirmed the belief in transubstantiation and the importance of all seven sacraments.

- They reaffirmed the authority of both scripture the teachings and traditions of the Church.

- They reaffirmed the necessity and correctness of religious art (see below).

The Council of Trent on religious art

At the Council of Trent, the Church also reaffirmed the usefulness of images—but indicated that church officials should be careful to promote the correct use of images and guard against the possibility of idolatry. The council decreed that images are useful “because the honor which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which those images represent” (in other words, through the images we honor the holy figures depicted). And they listed another reason images were useful, “because the miracles which God has performed by means of the saints, and their salutary examples, are set before the eyes of the faithful; that so they may give God thanks for those things; may order their own lives and manners in imitation of the saints; and may be excited to adore and love God, and to cultivate piety.”

Violence

The Reformation was a very violent period in Europe, even family members were often pitted against one another in the wars of religion. Each side, both Catholics and Protestants, were often absolutely certain that they were in the right and that the other side was doing the devil’s work.

The artists of this period—Michelangelo in Rome, Titian in Venice, Albrecht Dürer in Nuremberg, Lucas Cranach the Elder in Saxony—were impacted by these changes since the Church had been the single largest patron for artists. And art was now being scrutinized in an entirely new way. The Catholic Church was looking to see if art communicated the stories of the Bible effectively and clearly (see Paolo Veronese’s Feast in the House of Levi for more on this). Protestants on the other hand, for the most part, lost the patronage of the Church, and religious images (sculptures, paintings, stained glass windows, etc.) were destroyed in iconoclastic riots.

Other developments

It is also during this period that the Scientific Revolution gained momentum and observation of the natural world replaced religious doctrine as the source of our understanding of the universe and our place in it. The Holy Roman Empire up-ended the ancient Greek model of the heavens by suggesting that the sun was at the center of the solar system and that the planets orbited around it.

At the same time, exploration, colonization, and (the often forced) Christianization of what Europe called the “New World” continued. By the end of the century, the world of the Europeans was a lot bigger and opinions about that world were more varied and more uncertain than they had been for centuries.

Please note, this tutorial focuses on Western Europe. There are other forms of Christianity in other parts of the world including, for example, the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Additional resources

Overview of the Reformation from BBC

Introduction to the Protestant Reformation: Setting the stage