Pop Art: It seems to glorify popular culture, but a second look reveals a critique of post-war marketing and consumerism.

Read Now >Chapter 76

Popular, Transient, Expendable: Print Culture and Propaganda in the 20th century

Introduction

In 1956, the British artist Richard Hamilton put forth a definition for a new artistic genre called Pop Art, which he described as:

Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business.

Suffice it to say, these are not words and concepts that we typically associate with fine art. Hamilton’s definition seems more suited to radio or magazine advertisements, which are cheap to produce and designed to get their point across as quickly as possible.

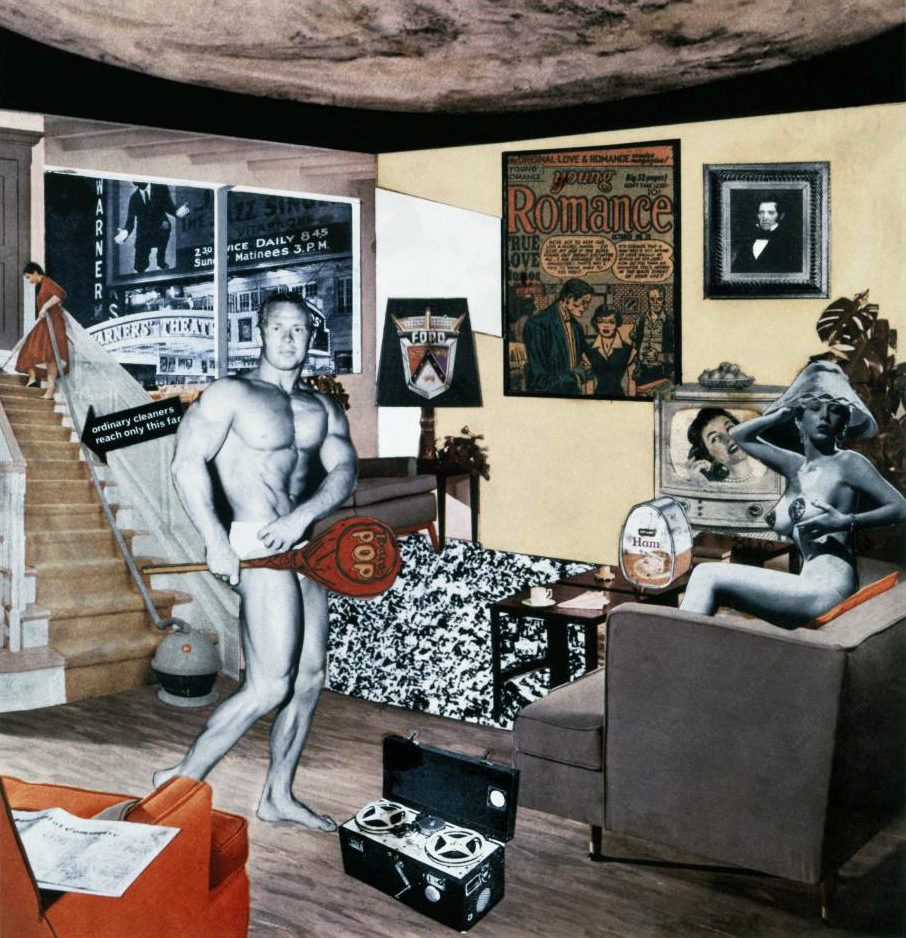

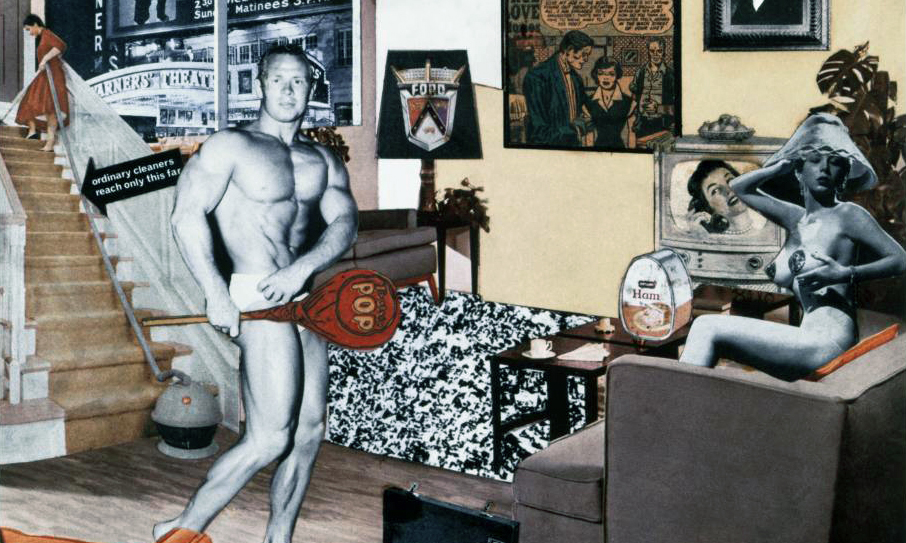

Look closely at this image: do you see any consumer products in it? Richard Hamilton, Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing?, 1956, collage, 26 cm × 24.8 cm (Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen)

Indeed, at a time when the consumer landscape was rapidly transforming (amidst political and economic shifts that followed World War II), the artist and his peers proposed that the art of their time should be responsive to the messages and images that surrounded them in the world of mass media.

This chapter explores the many ways in which art in the mid-to-late twentieth century engaged with the expansion of “mass media.” This term describes a range of technologies and platforms that were used to reach a large audience, such as television, newspaper, magazines, films, websites, and the advertisements or articles contained within them. Whether such media are harnessed by private entities, like corporations, or governments and public institutions, they are frequently used as tools of persuasion.

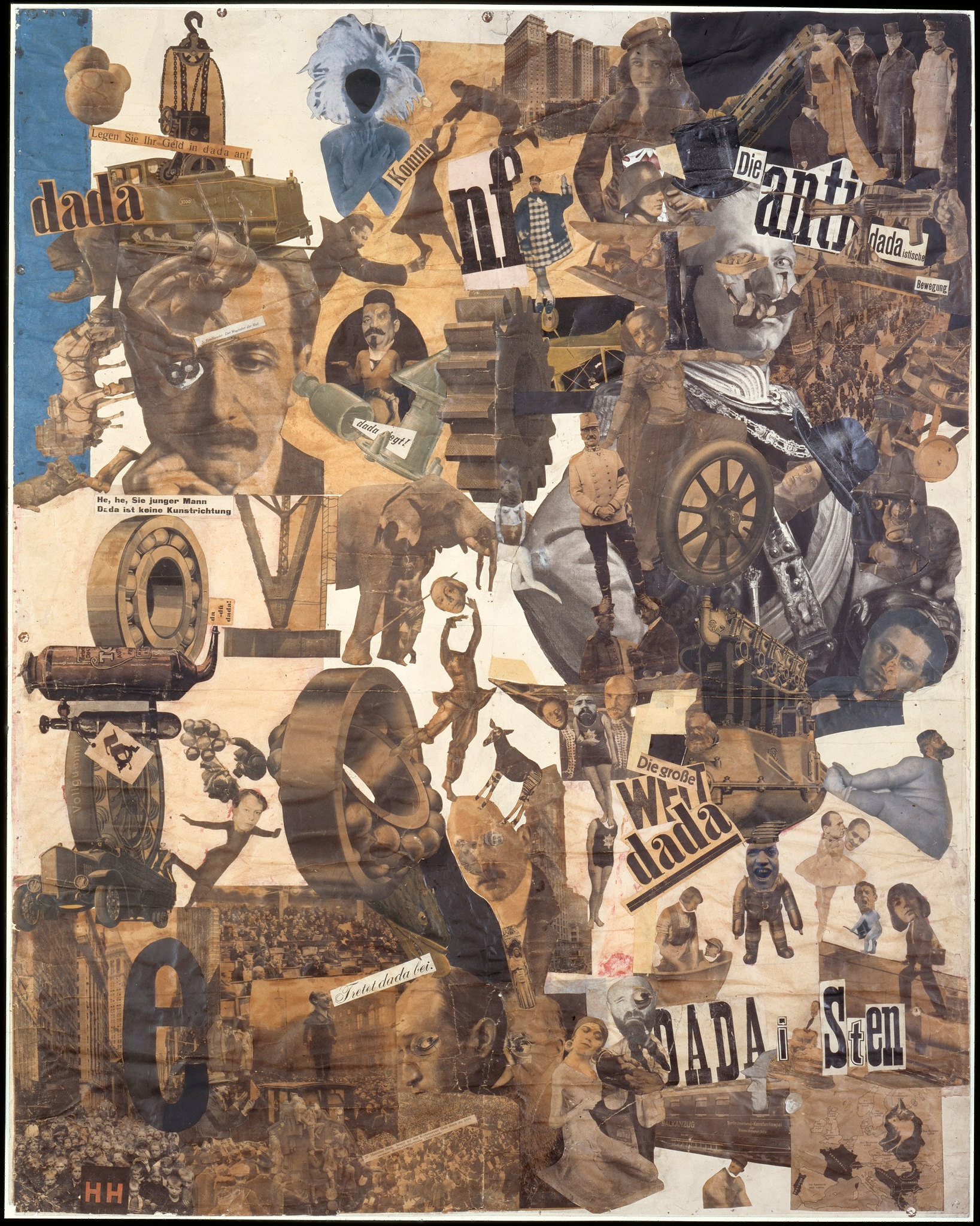

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, collage, mixed media, 1919–20

There is a precedent for Pop Art to be found in art history: Early in the 20th century, the photomontages of Dada artists like Hannah Hoch and John Heartfield incorporated newspaper clippings, photographs, and slogans to critique the Weimar government in Germany. After World War Two, artists likewise sought to reveal and critique the messages that such media contained, while also mirroring the visual forms of popular media, such as advertisements, in their art.

In the United States, for instance, manufacturing industries that had been mobilized toward the war effort were redirected, after the Allied victory, towards the production of consumer goods. In turn, advertisements flooded print and broadcast media. They featured idealized men and women who convincingly modeled a lifestyle of domestic bliss—one that could be attained through the purchase of beauty products, vacuum cleaners, furniture, and kitchen appliances. In turn, Pop artists utilized these tropes in works that were critical of the power that consumer culture wielded over the lives of everyday Americans. However, in socialist East Germany and communist China, such advertisements (and the products they featured) were rare. Instead, state-controlled media, as well as works of fine art, projected values of modest conformity and political allegiance. Artists like Sigmar Polke point out that despite the immense differences between these two historical contexts, the role of images in each society was entangled with power, authority, and persuasion.

Contemporary artists continue to engage in complex and critical ways with the archetypes and stereotypes that have circulated via mass media. Through these artists’ works, we can learn how to recognize and challenge the subtle messages contained in the many visual cultural forms that we interact with every day.

Pop! Postwar Consumerism and Commodity Culture

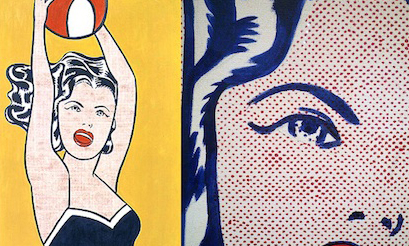

This section features examples of Pop Art—a movement known for its nuanced engagement with images of advertisements, products, and celebrities in the 1960s. While seeming to celebrate this consumerist turn in Western culture, these artists were actually critical of how society was changing amidst the abundance of mass-reproduced goods and images.

Among the artist Andy Warhol’s favorite motifs, for instance, was the grinning visage of Marilyn Monroe—one of the most famous movie stars of the 1950s. While his silkscreened portraits of the starlet might be mistaken as a celebration of her beauty and fame, the artist actually sought to reveal the darker side of celebrity culture. In Marilyn Diptych, for instance, created in the year following her death, Monroe’s portrait becomes faded over the course of its unending repetition. Warhol shows us the manufactured nature of the actress’s public image, but also the psychological damage that media attention and the public spotlight can engender. In addition, Tina Rivers Ryan explains in her article on “Marilyn Diptych” below that viewers should “consider the consequences of the increasing role of mass media images in our everyday lives.” Warhol makes this point clear by using silkscreen—a newer reproductive printing method that reduces his creative labor to that of a machine—thus removing any trace of the personal in his art. In each example below, Pop artists replicate and repeat common visual forms and subjects to help us understand them in new ways.

Essays and videos about Pop Art

Richard Hamilton, Just What is It . . . is considered to be among the most foundational works of Pop Art—even though the small collage was initially not created as a work of art.

Read Now >

Any Warhol, Marilyn Diptych: Warhol used a quasi-mechanical process of silkscreen to reproduce Marilyn Monroe’s familiar face again and again.

Read Now >

Roy Lichtenstein, Rouen Cathedral Set V: How do you make a nineteenth-century painting series ask twentieth-century questions?

Read Now >

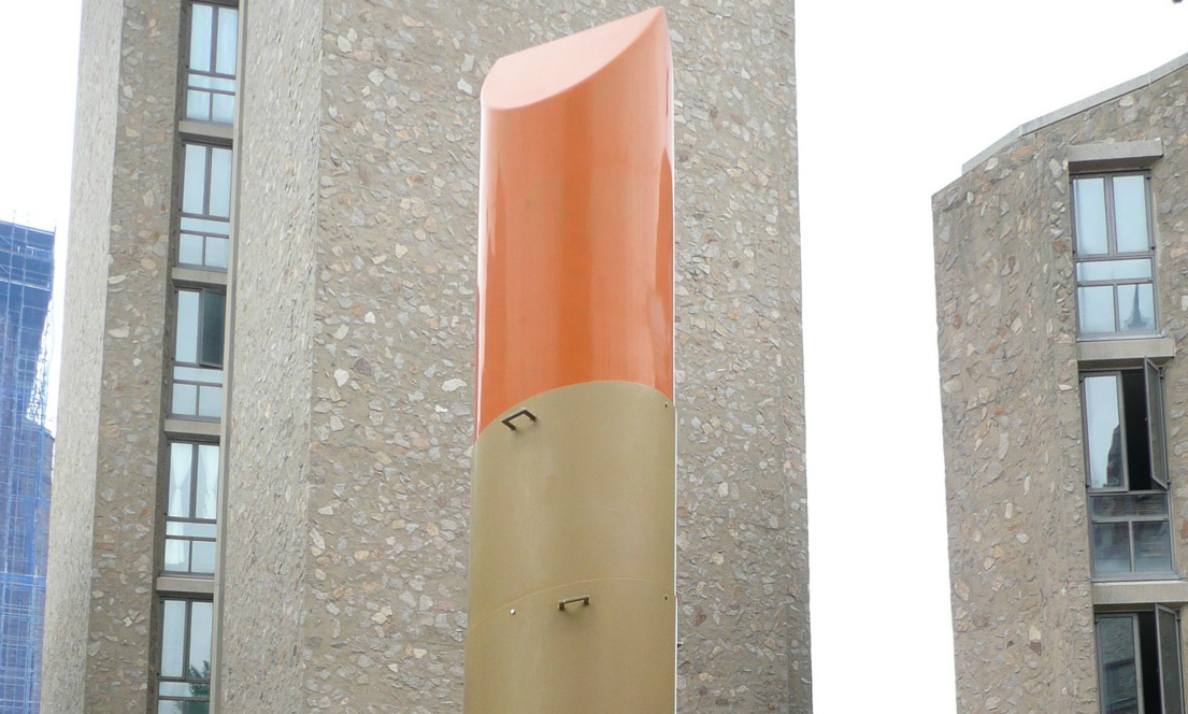

Claes Oldenburg, Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks: This sculpture, installed on the Yale campus during Vietnam War protests, was never meant to be permanent.

Read Now >

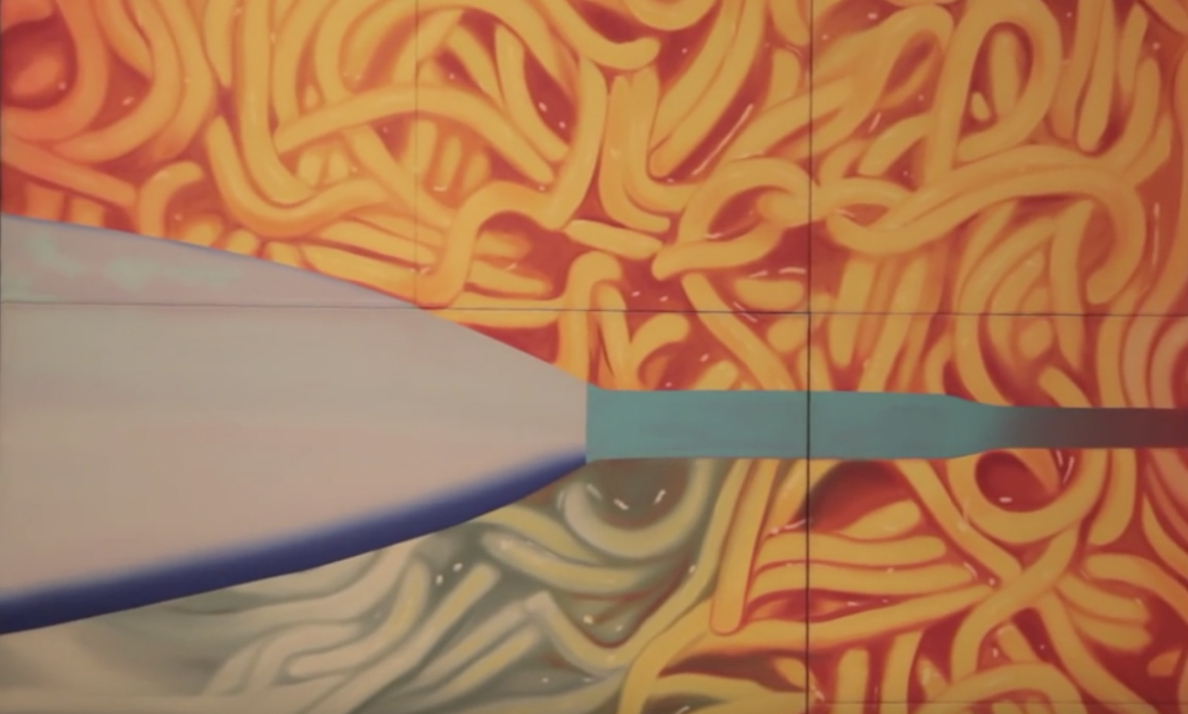

James Rosenquist, F-111: This war machine seemed obsolete before it was finished; Rosenquist explains why he painted it with SpaghettiOs.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Socialist and Capitalist Realism

What was the role of mass media within socialist societies in the mid-twentieth century, and how did artists either support or critique this phenomenon? The works below represent examples of visual art that functioned as state propaganda, as is the case in Liu Chunha’s painting of Chairman Mao, created in Communist China. Artists also used their work to show how both democratic and socialist societies utilize images as tools of persuasion or to convey collective values—whatever these may be. At the height of the Cold War, for instance, the artist Sigmar Polke moved from his hometown in the Communist-run Eastern Bloc to Dusseldorf—a city in West Germany. The cultural and economic differences that he witnessed across the Iron Curtain—the political boundary that separated Soviet territories from Western Europe—were stark: West Germans enjoyed a state of abundance in a democratic, capitalist society, where modern amenities and consumer products were widely available. Meanwhile, East Germans lacked access to even basic necessities. However, Polke also noticed that visual culture and mass media functioned in much the same way in each locale, despite differences of appearance. Polke’s own style of art, which he termed “Capitalist Realism,” addresses the use of visual media as tools of propaganda. This chapter looks at how art works, like other forms of visual culture, were utilized for political purposes during the Cold War era.

Essays and videos about Social and Capitalist Realism

Liu Chunhua, Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan: Chairman Mao is portrayed as a revolutionary leader championing the common people in this work of socialist realism.

Read Now >

Sigmar Polke, Bunnies: Hugh Hefner turned women into objects, and Sigmar Polke turned those objects into dots.

Read Now >

Gerhard Richter, Uncle Rudi: Richter toys with both visual and ethical clarity in this evocative, ambiguous painting of an uncle lost to WWII.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Pictures Generation and Late Capitalist Aesthetics

Some economists refer to the postwar period (after 1945) using the term Late Capitalism, which describes the social impacts of free market systems, including income inequality, feelings of disconnection from society, and class divisions. As these conditions continued into the later decades of the twentieth century, artists began to reflect on the increasing power that advertisements, marketing, and corporate branding wielded not just on our personal lives but also in the art world and other creative industries.

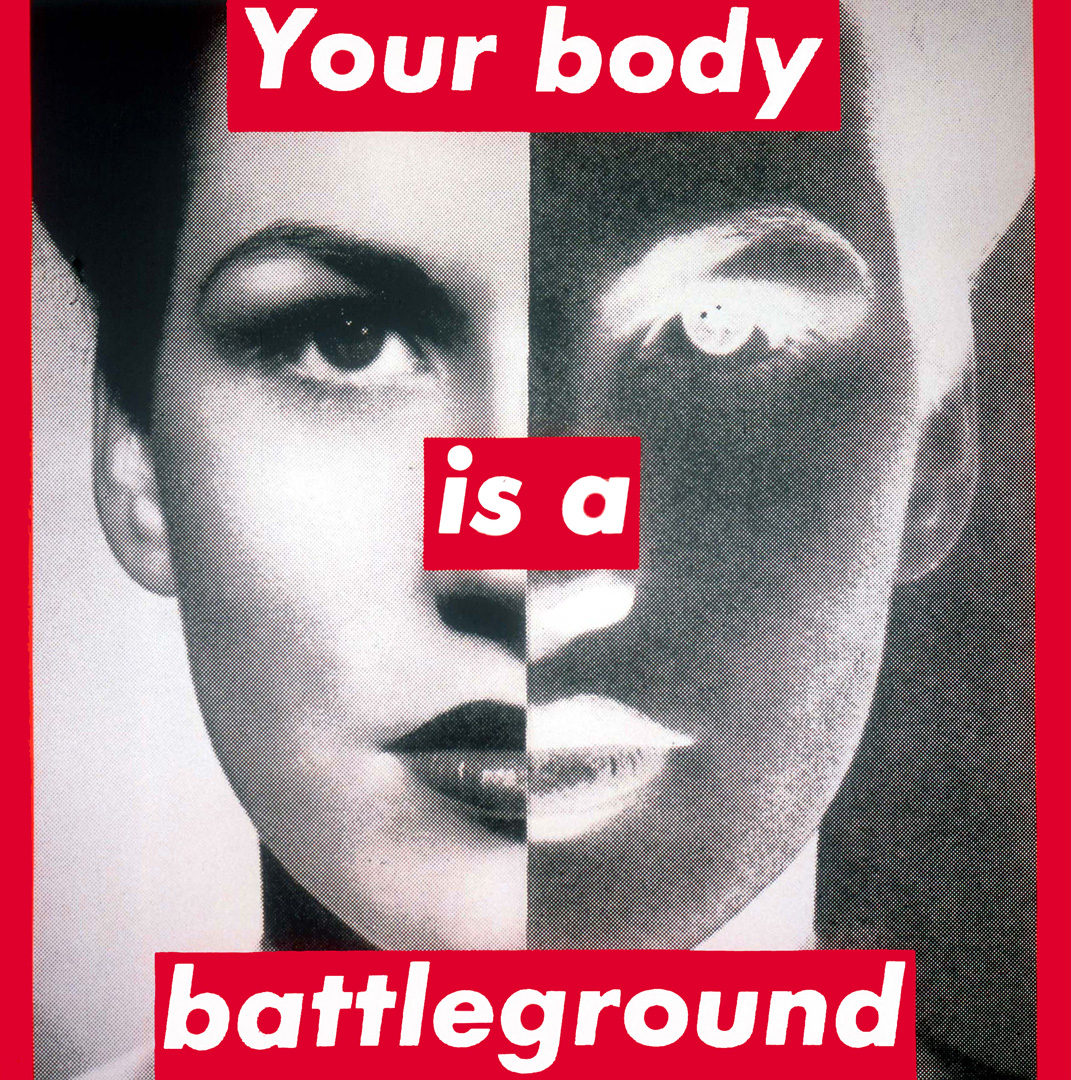

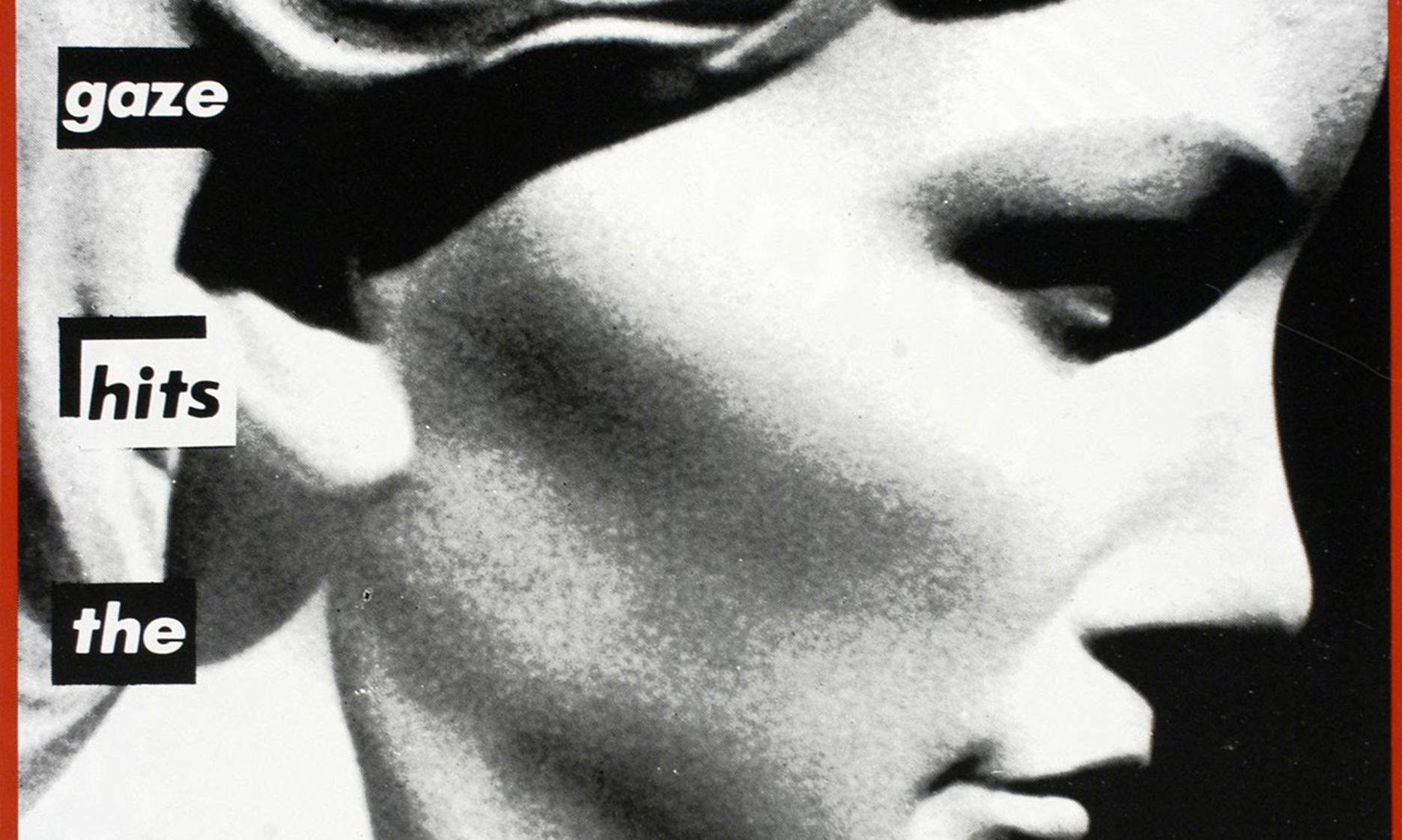

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989

In the late 1970s and 1980s, a number of New York-based artists (loosely referred to as the “Pictures Generation”) explored the subject of mass-reproduction in visual culture. For instance, Barbara Kruger used bold text and found photographs to create compelling, seemingly familiar slogans that work to activate viewers’ awareness of the persuasive media that surround us. While the Pictures Generation artists were more skeptical of corporate power, others leaned into this phenomenon, using savvy marketing tactics to “brand” and market their art. This is the case for the American Jeff Koons, known for his sleek, sexy, and highly commercialized style, as well as the “Young British Artists” (YBA)—a London-based cohort who graduated from art school around the early 1990s, and produced eclectic works that are brash, wry, and sometimes intentionally shocking. In very different ways, then, each of the works in this section reveal how inseparable art, consumerism, and real life became in the late twentieth century.

Essays and videos about the Pictures Generation and late capitalist aesthetics

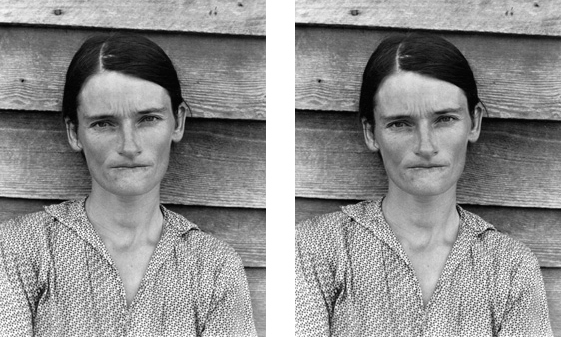

The Pictures Generation, an introduction: Through manipulation of media, these artists questioned the possibility and the significance of “originality.”

Read Now >

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face): Kruger’s art is characterized by a visual wit sharpened in the trenches of the advertising world.

Read Now >

The YBAs: The London-based Young British Artists—This loosely formed group of artists enlivened London’s contemporary art scene in the 1990s.

Read Now >

Jeff Koons, Pink Panther: Koons’s cartoonish life-size emblems of childhood innocence are an assault upon both sincerity and taste.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Contemporary Connections: Unpacking Archetypes

Advertisements, television shows, and other media often project harmful or generalizing stereotypes that have a wider impact on our society, and on the way we relate to one another. Many contemporary artists see their practices as an opportunity to deconstruct—or uncover and examine—such examples in both historical visual culture and today’s popular media. In this section, you’ll find examples of art works that confront the politics of representation and identity—especially in relation to race and gender—within media such as cinema, film stills, and advertisements for beauty products.

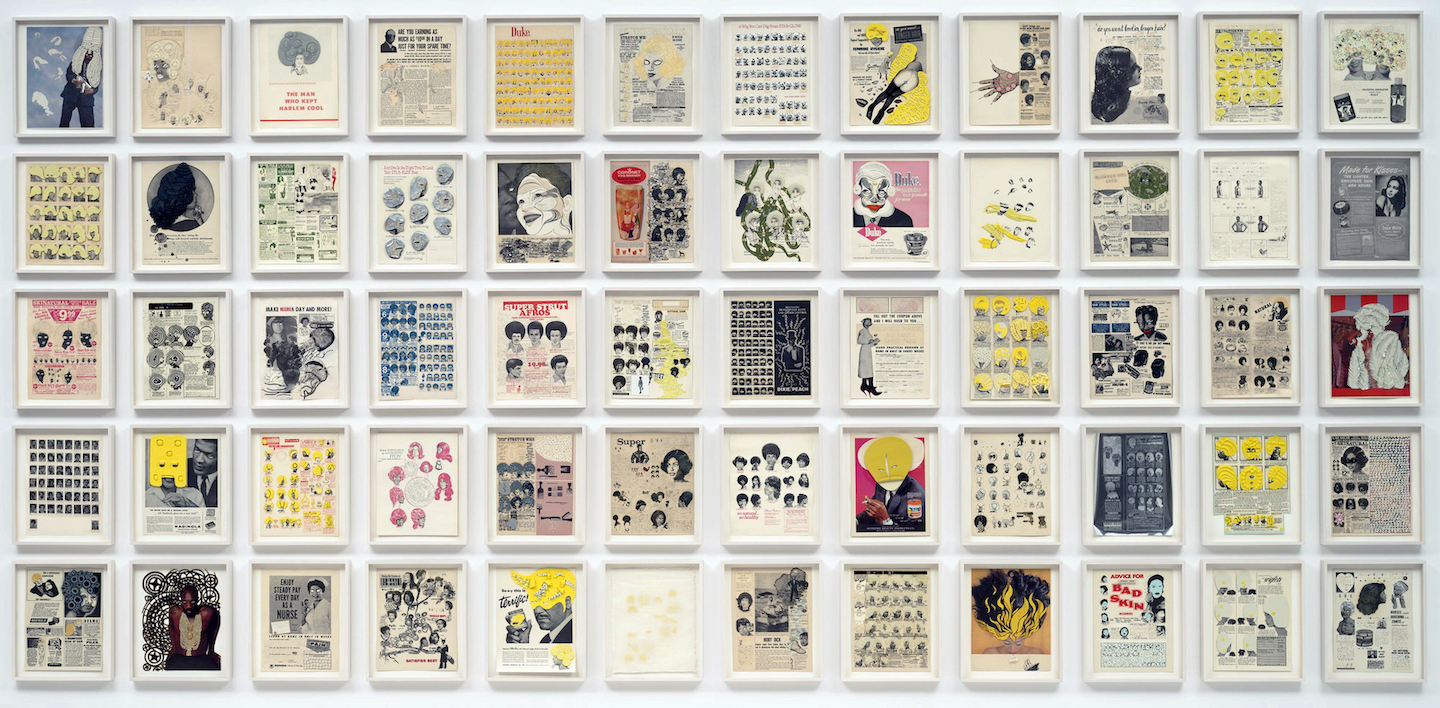

Ellen Gallagher, DeLuxe, 2004–05, portfolio of sixty with photogravure, aquatint, screenprint, lithograph, etching, and drypoint; some with modelling clay, laser-cut, collage, oil, gouache, pomade, metallic foil, graphite, varnish, acrylic medium, toy eyeballs, chine collé, acrylic, tattoo engraving, embossing, velvet, glitter, crystals, gold leaf, toy ice cube, and plastic sheet additions, each: 33 x 26.7 cm, overall: 213.4 x 424.2 cm (Museum of Modern Art; © 2021 Ellen Gallagher and Two Palms Press)

For instance, Ellen Gallagher’s paintings and collages feature fragmented and repeated images of wigs, lips, and eyes that are pulled from advertisements for beauty products targeted to Black women. The strategies of accumulation and repetition in Gallagher’s works invite us to notice how messaging about race, gender, and beauty are encoded. Likewise, in her photographic series Untitled Film Stills, the artist Cindy Sherman uses costumes, props, and settings to stage photographs that resemble mid-20th century Hollywood film stills. Sherman’s scenes are entirely fabricated, but their stylization appears so familiar to us because Hollywood tends to recycle the same archetypes over and over, especially in regard to female characters. These artists point out the ways in which entertainment media often guide our understandings of identity and difference.

Essays and videos about unpacking archetypes

Kara Walker, Darkytown Rebellion: Walker’s installation builds a world that unleashes horrors even as it seduces viewers.

Read Now >

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #21: Sherman creates a series of film stills starring herself—but there is no film.

Read Now >

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman Feeding Bird), The Kitchen Table Series: Weems sets her series around the kitchen table, a metaphor for the intimate spaces of home.

Read Now >/3 Completed

As different as they are, each of these movements demonstrates that visual art is often inseparable from the world of mass communication. Whether artists are aiming to support or critique the agendas that are put forth by political and economic authorities, their work can help us to learn how to think more actively about the messages that are encoded in the popular and visual culture that surround us every day.

Key questions to guide your reading

What can an art work that uses mass media imagery reveal to us about the sources from which such media derive?

Do you think that art can be as effective a tool of mass communication as newspapers or advertisements?

How can we tell when an artist is celebrating or critiquing the mass media of their time?

How have contemporary artists from the 1960s to the present worked to challenge the dominant narratives that are projected through both public and private mass media?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat can an art work that uses mass media imagery reveal to us about the sources from which such media derive?

Do you think that art can be as effective a tool of mass communication as newspapers or advertisements?

How can we tell when an artist is celebrating or critiquing the mass media of their time?

How have contemporary artists from the 1960s to the present worked to challenge the dominant narratives that are projected through both public and private mass media?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

appropriation

Capitalist Realism

identity politics

mass media

Pictures Generation

Pop Art

silkscreen

Socialist Realism

Young British Artists

Learn more

Coming soon!