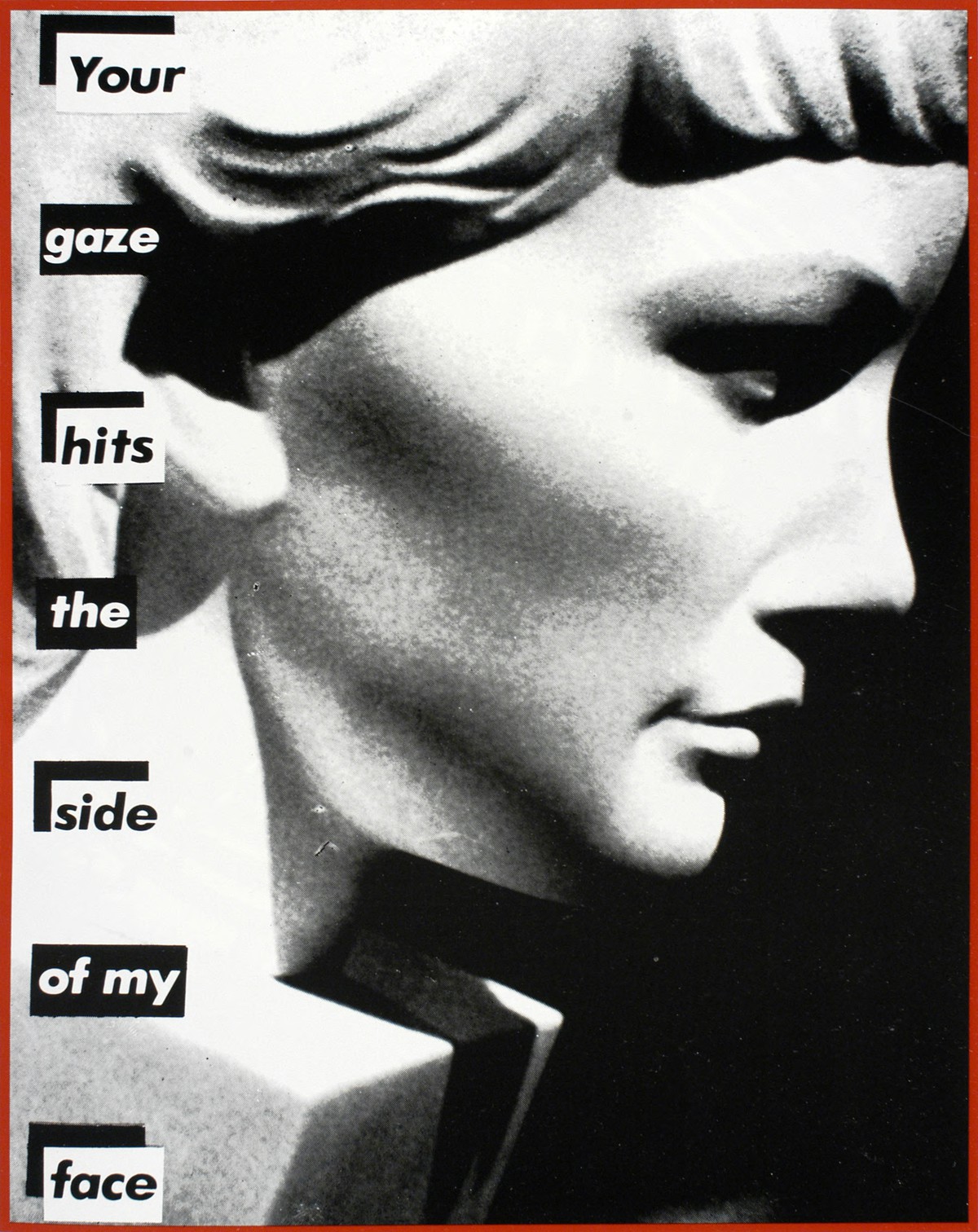

Has an artwork ever been more direct in acknowledging that the simple act of looking is a gendered (and gendering) act? “Your gaze hits the side of my face,” admonishes Barbara Kruger in Untitled (1981). The phrase is made stark and impersonal by arranging the words in a vertical stack, like those of a ransom note, to the left of a photograph of a female portrait bust in profile. Notice how the head is equally depersonalized; a stylized version in the classical tradition whose neck disappears into a block of stone, the suggestion here is that women are rendered inert in the act of being looked at. With an assumed male viewer — the subject of the possessive phrase “your gaze” — the subject of the portrait bust readily conforms to patriarchal fantasies of the passive female object.

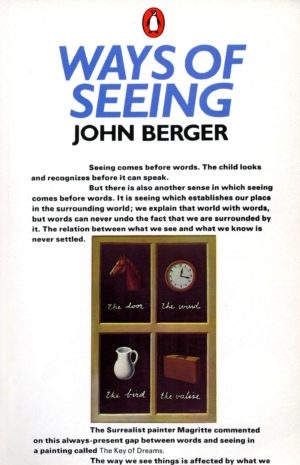

In 1981 the concept of the male gaze spelled out a crucial problematic of feminist theory. Could women truly be liberated from the objectification implied in this act of being looked at? John Berger in his 1972 book Ways of Seeing described the history of Western oil painting as a catalogue of submissive nude women arranged for the pleasure of male viewers. Kruger confronts this tradition head on. The phrase “male gaze” referenced in Kruger’s title is taken from Laura Mulvey, who coined the phrase in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” a landmark text of feminist theory.

Kruger’s art is characterized by a visual wit sharpened in the trenches of the advertising world where the savvy combination of graphic imagery and pithy phrasing targeted a growing population of consumers in the post-World War II years. The portrait bust she uses for Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face) is a found picture, one of any number the artist would have encountered in her early career in graphic design. This included a stint at Mademoiselle magazine, whose glossy pages were a virtual catalogue of stereotypical images of femininity. In the late 1970s, Kruger began to choose for her photomontages images of women that were often heightened examples of such stereotypes to which her addition of text would, often humorously, expose and thereby deconstruct the supposed realism of such imagery.

A 1982 work, for example, shows a silhouette of a woman’s body partially outlined by dressmaker’s pins and leaning forward in a chair marked with the words “We have received orders not to move.” The text here is laid across the body’s midsection, adding another layer of the idea of being pinned in place. The sense that women were trapped or immobilized in the act of being seen runs throughout her body of work from this period and underlines how common this kind of depiction of women was in advertising, particularly during the mid-twentieth century, the period from which many of Kruger’s images were culled.

Kruger offers some resistance to the objectifying gaze of the titular male viewer. Only hitting the side in Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face), one imagines it bouncing off as if merely ricocheting. But it nevertheless makes strategically visible the tacit assumption of Western visual traditions: women are looked at; men do the looking. In feminist terms, this means that women are negatively defined as lacking subjectivity or agency. Kruger staged an intervention, one could say, and it is in this way that her work is considered part of the feminist art canon.

Left: Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (detail), 1972 (Henry Moore Foundation); right: Sylvia Sleigh, The Turkish Bath, 1973 (Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Purchase, Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, 2000.104)

During the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, women artists sought, in different ways, to confront the problem of women’s representation in art. Sylvia Sleigh’s painting The Turkish Bath (1973), for example, renders a group of nude men in a traditional portrait genre usually reserved for women typified by the Neoclassical painter Jean-Dominque Ingres. Other artists, like Eleanor Antin (who also riffs off the classical sculptural tradition in Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, an important antecedent for Kruger) sought to subvert the usual depiction of women through unidealized and un-sexualized representations of the artist’s own body.

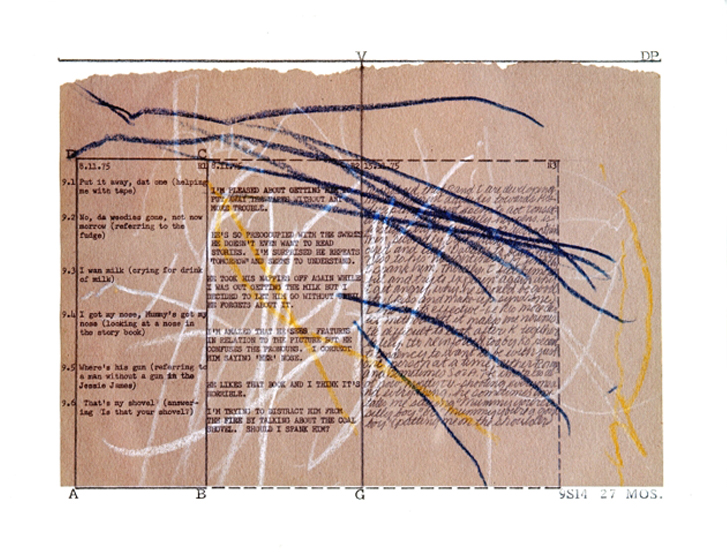

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, 1973–79, perspex units, white card, sugar paper, crayon, 1 of the 13 units, 35.5 x 28 cm each

A different tactic was to refuse representation of women’s bodies altogether. Mary Kelly’s monumental Post-Partum Document (1975), while an extensive portrayal of female subjectivity in relation to the mother-child relationship in psychoanalytic terms, makes no visual reference to herself or her body. Yet another approach was to develop a separate aesthetic predicated entirely upon women’s experiences: Womanhouse was created by Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago in the early 1970s as a space to showcase feminist performances about rape or installations about menstruation. Finally, there is the use of craft traditions typically associated with the domestic labor of women. Elevating “craft” to a fine art became a symbol of the elevation of women themselves as they strove for inclusion and representation. Kruger’s first artworks, in fact, were wall hangings that reframed craft in feminist terms. Despite the variances in approaches, at issue in feminist art practice was the place of imagery of women and artwork by women within patriarchy and in dialogue with political issues around gender and sexuality.

Kruger’s work differs from her predecessors whose work I have just briefly outlined. She came of age as an artist at a time when many were taking existing imagery and then re-staging it in slightly altered form. The term for this was “appropriation,” and it defined the strategy of a new generation of artists who wanted to refute modernism through invalidating ideas of originality, uniqueness, and even authorship. They became known, as did Kruger, as postmodern artists. Interestingly, many of these artists were women. Already critical of modernism because of its male-centered ideology, they filled the ranks of postmodernism to such extent that the critic Craig Owens described this congruence as a “crossing of the feminist critique of patriarchy and the postmodernist critique of representation.” Sherrie Levine re-photographed a suite of images by the photographer Walker Evans in order to void his authorship. Cindy Sherman appropriated the cinematic tropes of Hollywood whose stock and trade was the vulnerable female in trouble and re-staged them using herself as model. While feminist art (and postmodern art) was largely a white movement, later artists such as Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems or Kara Walker would expand upon these earlier artistic strategies to address the intersection of race and gender.

The art of the “Pictures Generation” as these postmodern artists came to be called, was glossier, slicker, and more enamored of media culture than what had come before, to such an extent that the cultural critic Fredric Jameson worried that art and advertising had become one. Of course the aim was to critically analyze such imagery; Kruger redeployed its seductive techniques, usually pressed into the service of enticing consumers (and historically much of it was aimed at women consumers), to expose the subtle and pervasive ways in which stereotypes of gender roles were reinforced through advertising and cinema (later works by Kruger would target consumerism directly).

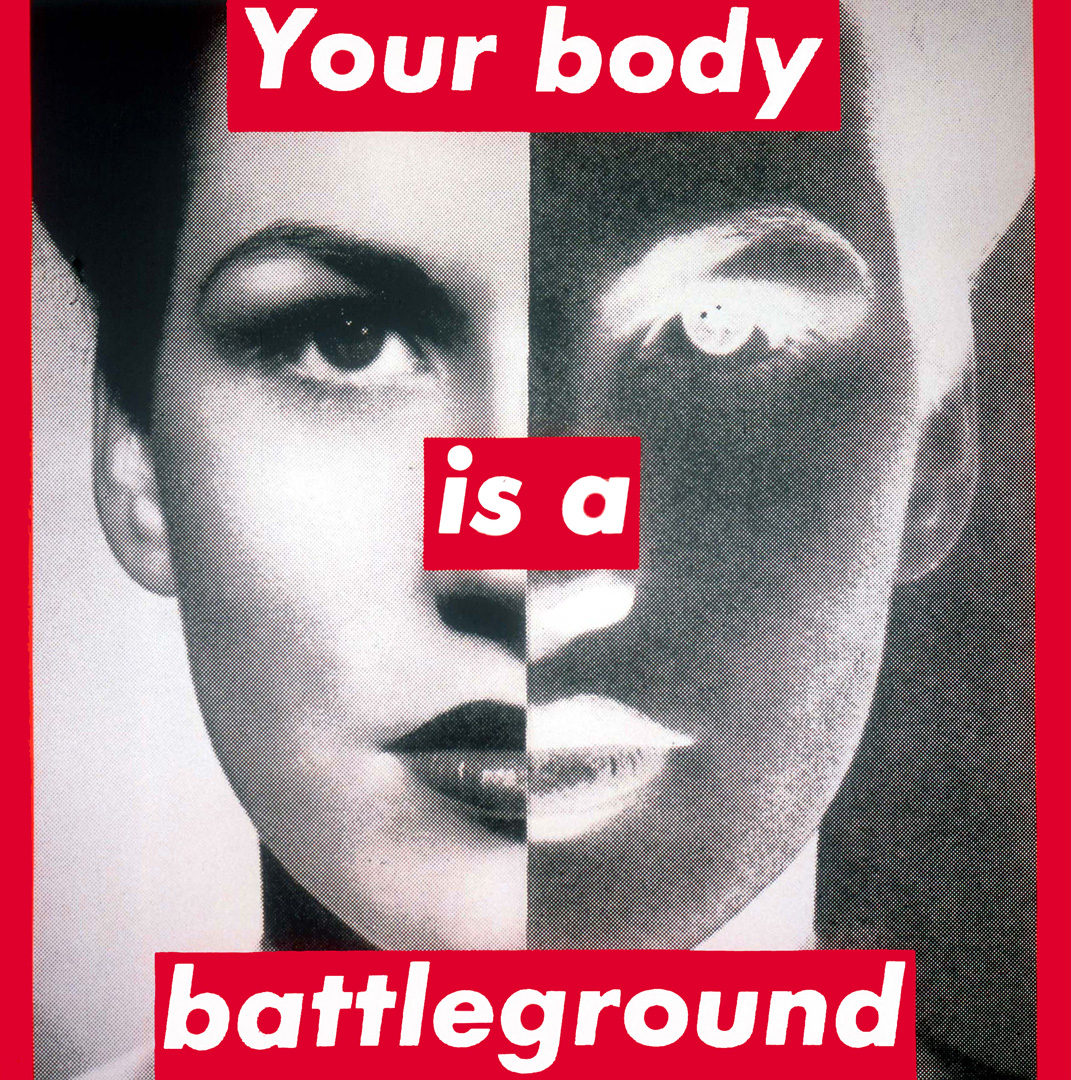

Deconstructing the supposed naturalism or ordinariness of these cultural fictions of femininity took on, within the larger political context of the feminist movement, an often agitprop or activist gloss. “Your body is a battleground” was produced for a 1989 women’s march on Washington. Confining her imagery to black and white with the eventual addition of red was clearly a nod to the photomontages of Russian avant-garde artists in the early twentieth century. In the first years after the Russian Revolution, artists sought to harness the power of technology using photography and film to reach mass audiences and unmask false ideologies.

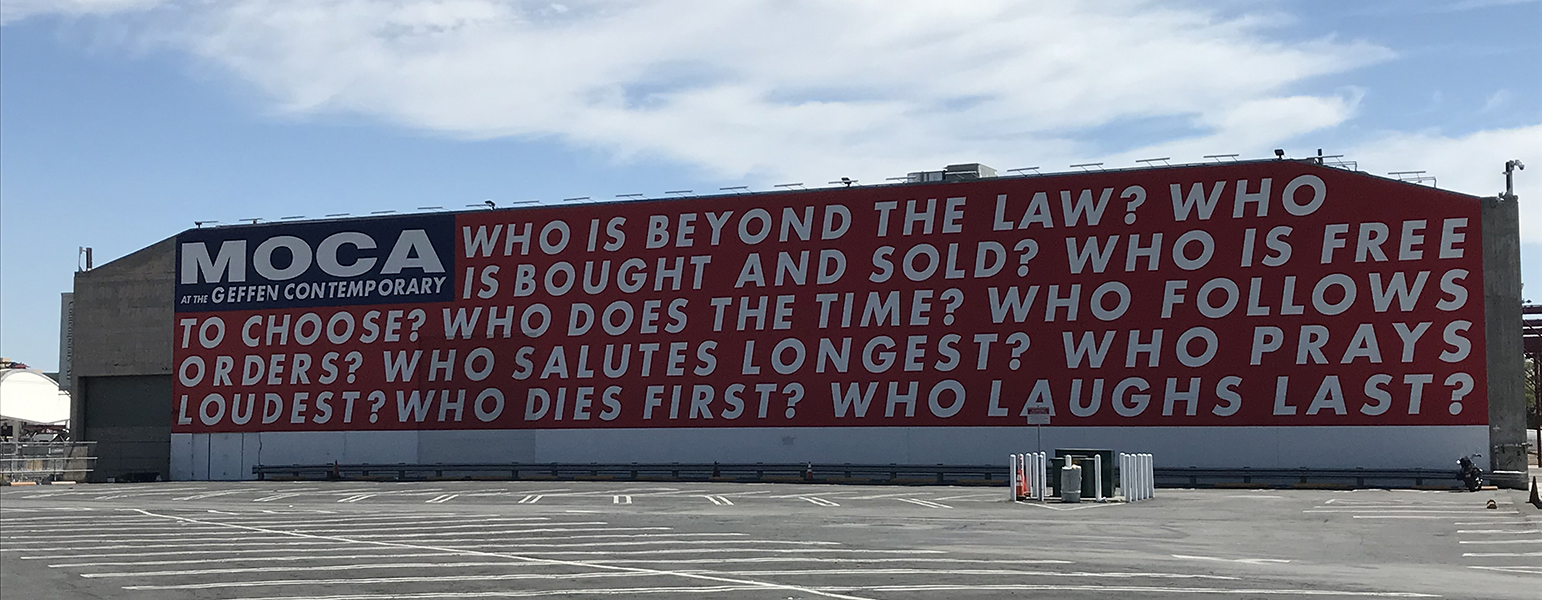

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Questions), 1990/2018 (Geffen Contemporary; photo: rocor, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Much like the factory murals and posters of Russian avant-garde art, Kruger sought a broader audience outside the gallery. Her work would appear on billboards, train station platforms, bus stops, public parks, and even matchbook covers. In the early 2000s the street clothing brand Supreme acknowledged that Barbara Kruger was an inspiration for their logo, a white Futura font within a red box. Despite its critical stance toward the advertising industry, Kruger’s unique graphic style couldn’t help but ultimately become influential in packaging and product design. Had Jameson been right about the collapse of art and advertising? Did the promotional and publicity structures of a consumer society eventually absorb postmodernism and thereby render its critique neutral?

Additional resources:

By art21. While sharing her earliest influences and what led her to become an artist, Barbara Kruger explains the origins of her 2017 Performa commission, “Untitled (Skate),” a site-specific installation at Coleman Skatepark in New York City’s Lower East Side. Growing up in a working class family in Newark, New Jersey before landing a job as a designer for Condé Nast publications, Kruger considers how her design experience lent a fluency and directness to the development of her text-driven work. “Money talks. Whose values?” says Kruger, quoting some of the panels installed in the skatepark. “These are just ideas in the air and questions that we ask sometimes—and questions that we don’t ask but should ask.” Direct not just in its address of the viewer, but also in its active engagement with social and political events, Kruger’s work uses the visual language of advertising to critique the very messages it emulates. Her work asks viewers to closely consider how global topics like consumerism and power play a role in their daily lives. “Something to really think about is what makes us who we are in the world that we live in.” says the artist. “And how culture constructs and contains us.”

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3, (Autumn 1975): 6–18.

- Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism,” in Hal Foster, ed., The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture (Seattle: Bay Press 1983): 78.