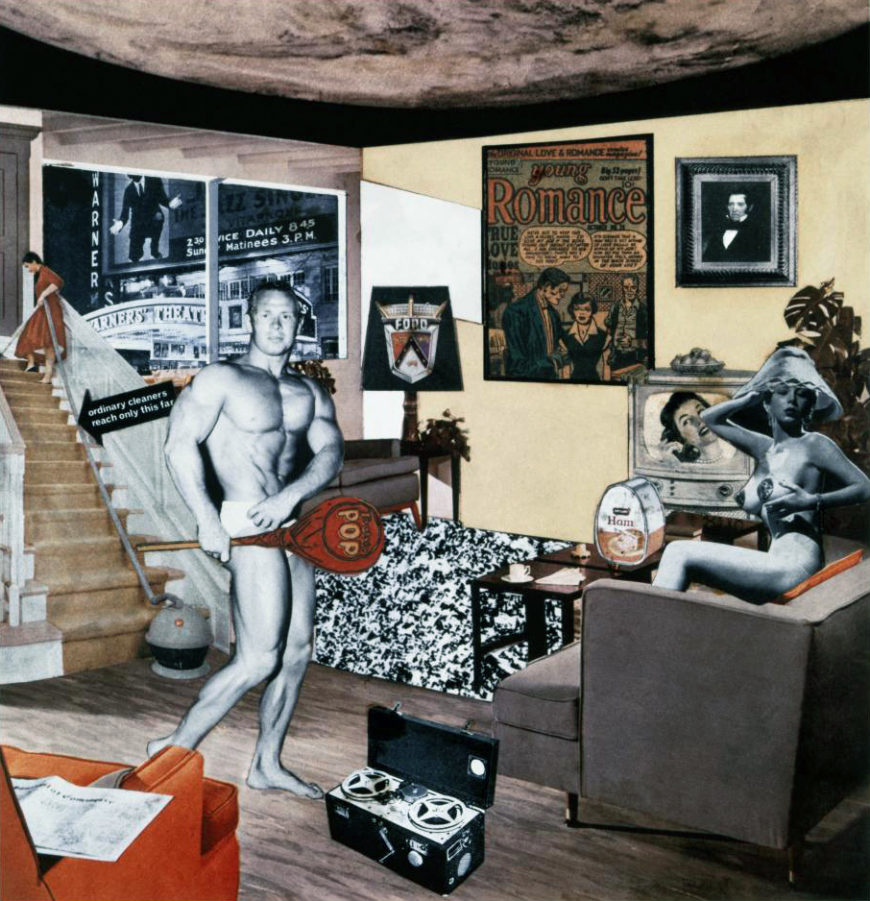

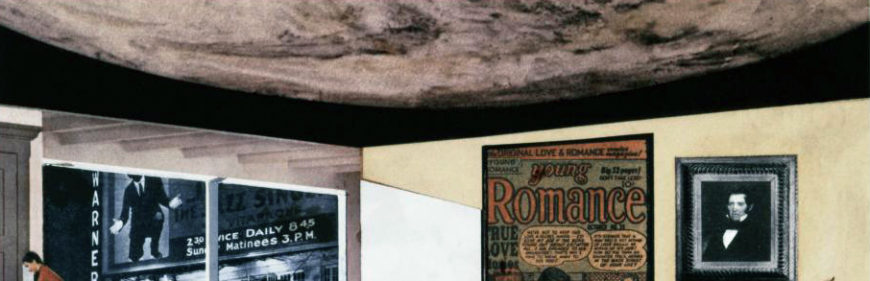

Richard Hamilton, Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing?, 1956, collage, 26 cm × 24.8 cm (Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen)

Consumer products and mass media

Richard Hamilton, Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing?, 1956, collage, 26 cm × 24.8 cm (Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen)

In this iconic collage by the British artist Richard Hamilton, created in 1956, a midcentury living room is filled to the brim with logos and cut-out images of consumer products. At center, a lampshade is emblazoned with the emblem for the auto manufacturer, Ford. The cover of a comic book hangs as “wall-art” and a can of tinned ham sits on the coffee table, like a decorative vase. Found images and mass media artifacts are everywhere we look in this image—on the television, out the window, up the stairs, and on the floor.

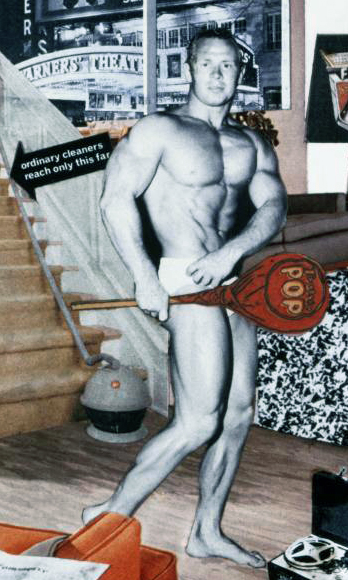

In fact, even the couple who occupy the room appear to us as commodities. The wife, a nude model, is perched seductively on the couch, while the husband, a Herculean body builder, shows off his covetable physique, wielding a suggestive Tootsie pop by his waist. Often interpreted as a kind of idealized, modern-day “Adam and Eve,” the couple are also products on display, no different from the branded and packaged goods that adorn their home.

The title of this art work takes the form of a question—Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing?—phrasing that echoes the titles of articles in popular magazines and which can be answered somewhere in the dizzying array of consumer imagery strewn across its the work’s surface. The domestic space, Hamilton asserts, has become prime real estate for the advertising industry, and is an arena in which middle class aspirations are on full display in the form of futurist vacuum cleaners and television sets.

Following the victory of Allied forces in World War Two, the United States in particular experienced a period of economic bounty; factories that had been mobilized to create airplanes, artillery, and other military necessities were repurposed towards the manufacturing of popular culture, luxury items, and household products that were then exported worldwide. Produced amidst the arrival of American goods in the United Kingdom, Hamilton’s collage is one of the first works of what would be later known as the Pop Art movement: a genre which both celebrated and critiqued subjects such as consumerism, celebrities, and the cheapening of modern culture amidst the turn towards mass-production.

Pop Art’s British origins

While many of the most recognizable names in Pop Art are American artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenberg, who created paintings and sculptures inspired by comic books and advertisements throughout the 1960s, the movement actually originated in postwar London. In fact, a half decade before Warhol exhibited his famous Campbell’s Soup paintings, it was Hamilton who gave the movement its first official definition. Describing his ideas to his friends, the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, Hamilton wrote that:

Pop Art is: Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business Richard Hamilton, Letter to Peter and Alison Smithson, 16 January 1957

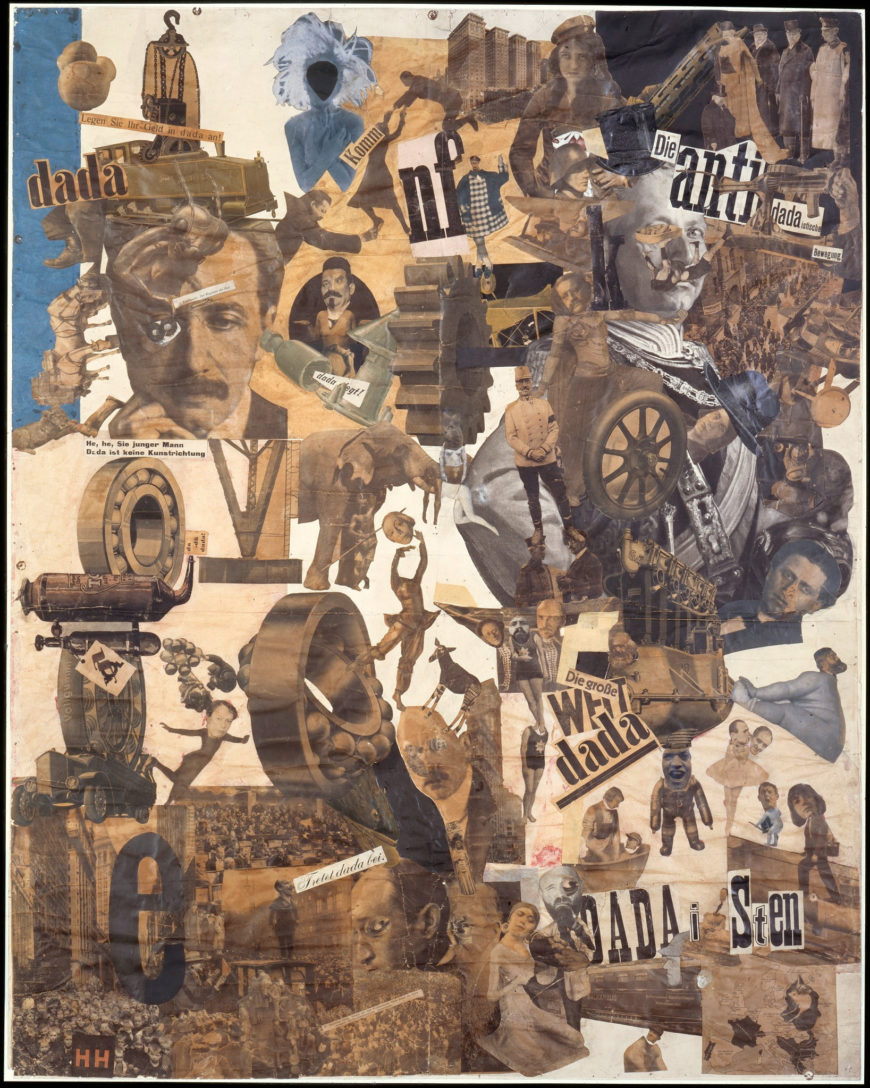

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1919–20, collage, mixed media

The terms above were rarely used in relation to fine art, which is normally ascribed a sense of timelessness, seriousness of purpose, and significant material value. Pop artists sought to challenge the elitism of the academic tradition, much like the artists of the Dada movement of the World War I era, who challenged the way in which art is often used as a symbol of socio-economic status. Pop artists were interested in critiquing the status of art as a commodity object, and often depicted or made use of artifacts of popular culture, advertisements, and mass media.

In Britain, Pop Art developed alongside a similar turn in intellectual history. For instance, the New Left writer Raymond Williams wrote an important essay called “Culture is Ordinary” in 1958, which proposed that we should not think of “culture” as a term that applies only to pursuits of the leisured class. He wanted scholars to examine a broader definition of culture as a “whole way of life” whose expression is evident in popular films, novels, advertisements, and other mass-produced media. Art critic Lawrence Alloway, who coined the term “mass popular art” in 1955, likewise argued for the importance of art that engaged with mass communications and contemporary visual culture. [1] Similarly, Pop artists like Richard Hamilton were interested in drawing our attention to the desires, culture, homes, and interests of regular, everyday people—not just the financial elite.

The Independent Group and “This is Tomorrow”

While Just What is It… is considered to be among the most foundational works of Pop Art, this small collage was initially not created as a work of art. At just 12 inches square, it was produced as the cover design for the catalogue of an exhibition called This is Tomorrow, an immersive, collaboratively produced installation of art and design that was conceived by a collective called The Independent Group, of which Hamilton was part.

An advertisement for the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s futuristic exhibition ‘This is Tomorrow’. 1956

The Independent Group was a cohort of young artists, designers, architects, and writers affiliated with the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. At the time, the museum typically exhibited Modernist paintings and sculpture, but by the late 1950s this kind of art felt out-of-step with the contemporary moment. In the early 1950s, members of the Independent Group met to discuss topics in visual culture that lay outside the traditional arena of fine art.

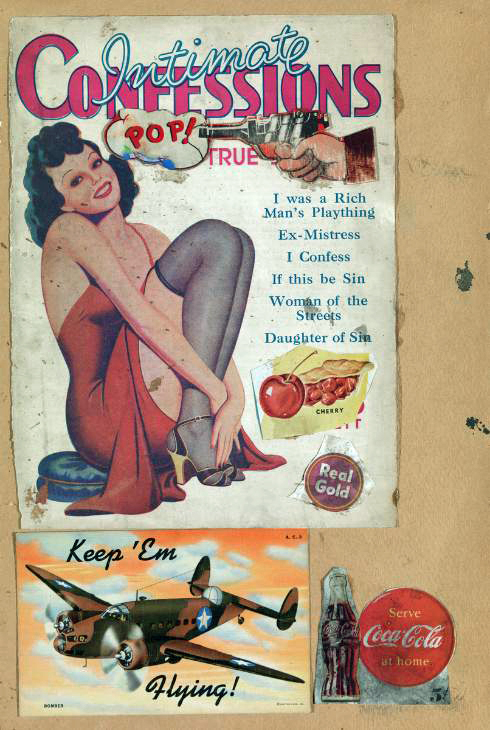

Eduardo Paolozzi, I was a Rich Man’s Plaything, 1947, printed paper on card, collage in Bunk!, 35.9 × 23.8 cm (Tate)

In 1952, Eduardo Paolozzi, for instance, gave a lecture entitled ‘Bunk!’ that was illustrated by projections of collages made from comic book clippings, magazine advertisements, film stills, and photographs of celebrities. [2]

Cardboard cutout of Robby the Robot in the This is Tomorrow exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 1956

In 1956, the Independent Group produced one of their most important exhibitions. Entitled This is Tomorrow, the show was held at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. It was divided into eleven immersive sections, each curated by a group of artists, architects, and other collaborators, who treated their contribution as a manifesto for contemporary, and future, visual culture. They each designed a poster and were given six pages in the exhibition catalogue.

Hamilton was a member of Group Two, along with architect John Voelcker, and fellow artists such as John McHale. Theirs was among the most memorable displays in This is Tomorrow; it featured dizzying Op Art panels and a life-size collage of cinema posters and cardboard cut-outs. For instance, that famous press photograph of Marilyn Monroe—flirtatiously posing above a breezy subway grate in The Seven Year Itch—was juxtaposed with Robby the Robot, an iconic character in the 1956 science-fiction film, Forbidden Planet.

Pop Culture in the Space Age

Art historians have traced many of the original contexts for the images that Hamilton collages in Just What is It…? For instance, the artist began the collage with a backdrop drawn from an advertisement for Armstrong Royal Floors, which was included in the June 1955 issue of the American magazine Ladies’ Home Journal.

This domestic interior scene provides the basic setting into which Hamilton pasted new images, such as the Hoover Constellations vacuum cleaner, Stromberg-Carlson television, and Armour Star Ham, among other products.

However, not every collage element comes from the marketing world.

Richard Hamilton, Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing?, 1956, collage, 26 cm × 24.8 cm (Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen)

For instance, Hamilton topped his domestic space with a planetary “ceiling”—a view of Earth, which had been photographed using an aerial camera at a height of about 100 miles. (This came from the personal archive of fellow artist McHale, who used collage elements to form images of futuristic, robotic creatures). Its inclusion complicates the sense of scale in Hamilton’s collage, as we move from the intimate space of a residential interior to the expansive realm of the cosmos.

It would be another fifteen years before the publication of the first photograph of Earth in its entirety—the so-called “Blue Marble” captured by the Apollo 17 crew in 1972—but both the Cold War and Space Age were on the horizon, and public fascination with planetary vision was already palpable in popular culture. As Hamilton himself later wrote:

We seemed to be taking a course towards a rosy future and our changing, Hi-Tech, world was embraced with a starry-eyed confidence; a surge of optimism which took us into the 1960s. Though clearly an ‘interior’ there are complications that cause us to doubt the categorisation. The ceiling of the room is a space-age view of Earth. The carpet is a distant view of people on a beach. It is an allegory rather than a representation of a room.[3]

As an allegory of the future—one marked by its fixation on “tomorrow”—Hamilton’s collage is one of the major works of the postwar age to truly represent what it means to be “contemporary.”