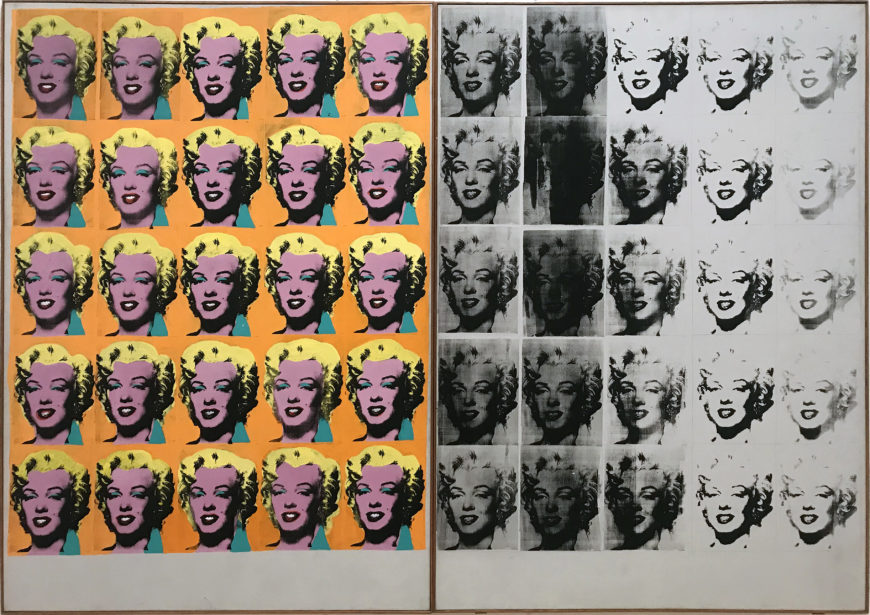

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962, acrylic on canvas, 2054 x 1448 mm (Tate) © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (photo: rocor, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych is made of two silver canvases on which the artist silkscreened a photograph of Marilyn Monroe fifty times. At first glance, the work—which explicitly references a form of Christian painting (see below) in its title—invites us to worship the legendary icon, whose image Warhol plucked from popular culture and immortalized as art.

Diptych with the Virgin and Child Enthroned and the Crucifixion, 1275–80, tempera on panel, 38 x 59 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

But as in all of Warhol’s early paintings, this image is also a carefully crafted critique of both modern art and contemporary life.

Not only pop culture

With sustained looking, Warhol’s works reveal that he was influenced not only by pop culture, but also by art history—and especially by the art that was then popular in New York. For example, in this painting, we can identify the hallmarks of Abstract Expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Visitor, Tate Modern, London (photo: Barbara Piancastelli, CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As in the work of these older artists, the monumental scale of Marilyn Diptych (more than six feet by nine feet) demands our attention and announces the importance of the subject matter. Furthermore, the seemingly careless handling of the paint and its “allover composition”—the even distribution of form and color across the entire canvas, such that the viewer’s eyes wander without focusing on one spot—are each hallmarks of Abstract Expressionism, as exemplified by Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. Yet Warhol references these painters only to undermine the supposed expressiveness of their gestures: like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, whose work he admired, he uses photographic imagery, the silkscreen process and repetition to make art that is not about his interior life, but rather about the culture in which he lived.

Emotional flatness

Warhol takes as the subject of his painting an impersonal image. Though he was an award-winning illustrator, instead of making his own drawing of Monroe, he appropriates an image that already exists. Furthermore, the image is not some other artist’s drawing, but a photograph made for mass reproduction. Even if we don’t recognize the source (a publicity photo for Monroe’s 1953 film Niagara), we know the image is a photo, not only because of its verisimilitude, but also because of the heightened contrast between the lit and shadowed areas of her face, which we associate with a photographer’s flash.

Publicity still for the film Niagara, 1953 left; center and right, details from: Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962, acrylic on canvas, 2054 x 1448 mm (Tate) © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

True to form, the actress looks at us seductively from under heavy-lidded eyes and with parted lips; but her expression is also a bit inscrutable, and the repetition remakes her face into an eerie, inanimate mask. Warhol’s use of the silkscreen technique further “flattens” the star’s face. By screening broad planes of unmodulated color, the artist removes the gradual shading that creates a sense of three-dimensional volume, and suspends the actress in an abstract void. Through these choices, Warhol transforms the literal flatness of the paper-thin publicity photo into an emotional “flatness,” and the actress into a kind of automaton. In this way, the painting suggests that “Marilyn Monroe,” a manufactured star with a made-up name, is merely a one-dimensional (sex) symbol—perhaps not the most appropriate object of our almost religious devotion.

Repetitions

While Warhol’s silkscreened repetitions flatten Monroe’s identity, they also complicate his own identity as the artist of this work. The silkscreen process allowed Warhol (or his assistants) to reproduce the same image over and over again, using multiple colors. Once the screens are manufactured and the colors are chosen, the artist simply spreads inks evenly over the screens using a wide squeegee. Though there are differences from one face to the next, these appear to be the accidental byproducts of a quasi-mechanical process, rather than the product of the artist’s judgment. Warhol’s rote painting technique is echoed by the rigid composition of the work, a five-by-five grid of faces, repeated across the two halves of its surface.

Detail, Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962, acrylic on canvas, 2054 x 1448 mm (Tate) © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (photo: rocor, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Here, as in many Neo-Dada, minimalist and conceptual works, the grid is like a program that the artist uses to “automate” the process of composing the work, instead of relying on subjective thoughts or feelings to make decisions. In other words, Warhol’s “cool,” detached composition is the opposite of the intimate, soulful encounter with the canvas associated with Abstract Expressionism. But whereas most works that use grids are abstract, here, the the grid repeats a photo of a movie star, causing the painting to resemble a photographer’s contact sheet, or a series of film strips placed side-by-side. These references to mechanical forms of reproduction further prove that for Warhol, painting is no longer an elevated medium distinct from popular culture.

Ghostly symmetry

Aside from radically changing our notion of painting, Warhol’s choices create a symmetry between the artist and his subject, who each seem to be less than fully human: the artist becomes a machine, just as the actress becomes a mask or a shell. Another word we could use to describe the presence of both the artist and the actress might be ghostly, and in fact, Warhol started making his series of “Marilyn” paintings only after the star had died of an apparent suicide, and eventually collected them with other disturbing paintings under the title “Death in America.” Her death haunts this painting: on the left, her purple, garishly made-up face resembles an embalmed corpse, while the lighter tones of some of the faces on the right make it seem like she is disappearing before our eyes.

Warhol once noted that through repeated exposure to an image, we become de-sensitized to it. In that case, by repeating Monroe’s mask-like face, he not only drains away her life, but also ours as well, by deadening our emotional response to her death. Then again, by making her face so strange and unfamiliar, he might also be trying to re-sensitize us to her image, so that we remember she isn’t just a symbol, but a person whom we might pity. From the perspective of psychoanalytic theory, he may even be forcing us to relive, and therefore work through, the traumatic shock of her death. The painting is more than a mere celebration of Monroe’s iconic status. It is an invitation to consider the consequences of the increasing role of mass media images in our everyday lives.

Additional resources

“Andy Warhol’s ‘Marilyn Diptych’, a Scene of Tragic Glamour” (Sotheby’s)

Hal Foster et al., Art Since 1900: modernism antimodernism postmodernism, 2nd ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2011).

Steven Henry Madoff, ed., Pop Art: A Critical History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

Kynaston McShine, ed., Andy Warhol: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1989).

Annette Michelson, ed., Andy Warhol (October Files) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).