Jeff Koons, Pink Panther, 1988, glazed porcelain, 104.1 x 52 x 48.2 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Jeff Koons

Banality

Jeff Koons, Pink Panther, 1988, glazed porcelain, 104.1 x 52 x 48.2 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Jeff Koons

Imagine walking into an art gallery and seeing overgrown toys, or cartoon characters presented as sculpture. If, in 1988, you had wandered into the Sonnabend Gallery on West Broadway in New York City, this is indeed what you would have witnessed: it was an exhibition entitled “Banality” by New York artist Jeff Koons presenting some twenty sculptures in porcelain and polychromed wood. The work certainly strikes as an affront to taste: the sculptures are highly polished and gleaming. The colors—muted pale blue, pink, lavender, green, and yellowish gold—seem to belong to the 1950s and 60s. The glossy textures look garish and factory-made, surfaces one associates with inexpensive commercial art. One would almost want to call these sculptures “figurines” were it not for their size. To add to this catalogue of horrors, the artist had farmed out the actual production to German and Italian artisans who made each work in triplicate! “Banality” thus debuted simultaneously in New York, Chicago, and Cologne.

A glazed porcelain statue entitled Pink Panther belongs to that body of work. It depicts a smiling, bare-breasted, blonde woman scantily clad in a mint-green dress, head tilted back and to the left as if addressing a crowd of onlookers. The figure is based on the 1960s B-list Hollywood star Jayne Mansfield—here she clutches a limp pink panther in her left hand, while her right hand covers an exposed breast. From behind one sees that the pink panther has its head thrown over her shoulder and wears an expression of hapless weariness. It too is a product of Hollywood fantasy—the movie of the same name debuted the cartoon character in 1963. The colors are almost antiquated; do they harken back to the popular culture of a pre-civil rights era as a politically regressive statement of nostalgia? And what about the female figure—posed in a state of deshabille (carelessly and partially undressed)? At a time of increased feminist presence in the still male-dominated art world this could only be perceived as a rearguard move. Or was Koons—a postmodern provocateur like no other—simply parodying male authority as he had done in some of his other work?

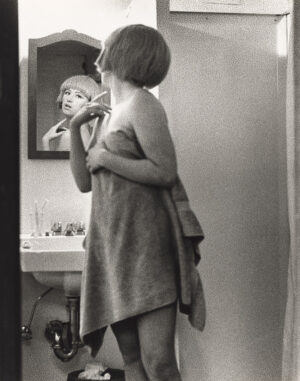

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #2, 1977, gelatin silver print, 24.1 x 19.2 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Cindy Sherman

Postmodernism: the artist as critic of mass culture

Provocation is a mainstay of the modernist avant-gardes reaching at least as back as far as when Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917, an ordinary urinal, was proposed as an artwork. But whereas Duchamp eventually accrued near-mythical status, that same critical reception for Koons was not forthcoming—in fact, he would become one of the first artists of this period to achieve a level of success that depended more on the art market than on art criticism. He is still reviled. In 2014 a review described Koons as “Duchamp with lots of ostentatious trimmings.” [1] It’s easy to see why he has continued to provoke: the postmodern 1980s inaugurated the contemporary sense of the artist as a critical and serious interrogator of mass culture and mass media. Cindy Sherman, one of the most prominent artists of that period, made photographs of herself that paraded the clichés of femininity before an audience that consumed critical theory about the constructed nature of reality and the oppressive manipulations of mass media. Her work was understood as a deconstruction (shorthand for the examination and analysis of the elements) of gender stereotypes. Another prominent postmodern artist of the period, Krzysztof Wodiczko, used high-powered projectors to cast politically charged imagery onto corporate façades after dark—imagery that often pointed to economic and social contradictions and prompted public discourse within an ephemeral and often provocative, public space.

Artists—postmodern artists—were supposed to counter the banality of evil that lurked behind public and popular culture, not giddily revel in it as Koons seemed to do. There appeared to be nothing serious about any of the works in the “Banality” exhibition: a life-sized bust of pop icon Michael Jackson and his pet monkey Bubbles; a ribbon-necked pig—especially egregious—in polychromed wood escorted by cherubic youths, two of which are winged. And of course Pink Panther, a work that seemed destined to insult rather than inform. It all seemed like kitsch posing as high art.

Jeff Koons, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, ceramic, glaze and paint, 106.7 x 179.1 x 82.6 cm (The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles) © Jeff Koons

Kitsch

What is kitsch? The American art critic Clement Greenberg once defined it as the opposite of what a truly progressive, avant-garde modernism embodied. Greenberg advocated for a modern art that was true to its materials, such as the gestural abstractions of New York School artists like Jackson Pollock, who splattered and spilled paint in abstract fashion on unprimed canvas—declaring a direct creative confrontation that was raw and honest. Kitsch, a word of German origin, refers to mass-produced imagery designed to please the broadest possible audience with objects of questionable taste (think of objects and images with popular, sentimental subject matter and style). Postmodern art attacked Greenberg’s influential theory of modern art, creating images in direct opposition to modernism. While modernism championed painting, form, and originality, postmodernism foregrounded photography, subject matter, and reproduction, and responded to modernism’s search for the profound by presenting the quotidian and banal aspects of experience. Postmodernism grounded the rarified atmosphere of genius that was prevalent in modernism in the politics of everyday life.

Jeff Koons, Ushering in Banality, 1988, wood and paint, 80.1 x 194.1 x 100 cm (Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; photo: Amaury Laporte, CC BY 2.0) © Jeff Koons

But postmodernism stopped short of fully embracing kitsch by insisting on a degree of self-aware critical distance. This is where Koons found a fault line that he fully exploited with works like Pink Panther. Hummel figurines and other popular collector’s items are the basis for the art in “Banality.” Koons rendered these saccharine and sentimental little figural groupings—cartoonish emblems of childhood innocence—at a life-size scale as an assault upon sincerity but also as an assault upon taste, and it is here that even the most daring of postmodern advocates drew a line in the sand. Like the modernist distinction between art and an everyday object drawn by Greenberg, Pink Panther challenged the distinction between an ironic appropriation of a mass-culture object and the object itself (seemingly without critical distance) thereby challenging the whole critical enterprise of postmodernism itself.