The figure is androgynous; the female pronoun is used here in keeping with the gender of the word melancholia, but some art historians believe the figure to be male. Her strong, muscular, substantial body and delicate wings epitomize her dilemma. She aspires to flight, yet is too heavy for her tiny wings to lift. Perhaps this is an allegory of hubris—the dangerous conceit that a mere human may become like a god. Flight is only for gods—as the unfortunate Icarus learned when he flew too close to the sun and the wax in his self-fashioned wings melted. The limits of mass and volume, of being a person in the world, prevent Melencolia’s flight—physical or creative. In a more prosaic fashion, this situation is familiar to anyone facing a demanding project. The desk is clear, the computer is on, books are in arm’s reach…and nothing happens.

Melencolia’s inertia has created chaos and neglect. Her creative frustration renders her unable to accomplish the simplest of tasks, such as feeding the malnourished dog who has grown thin from neglect. The image exudes physical and intellectual vertigo. Like the artist, we cannot quite figure out what to do, or where to look, or where we are. Are we indoors or out? Where does the ladder start? And where does it stop?

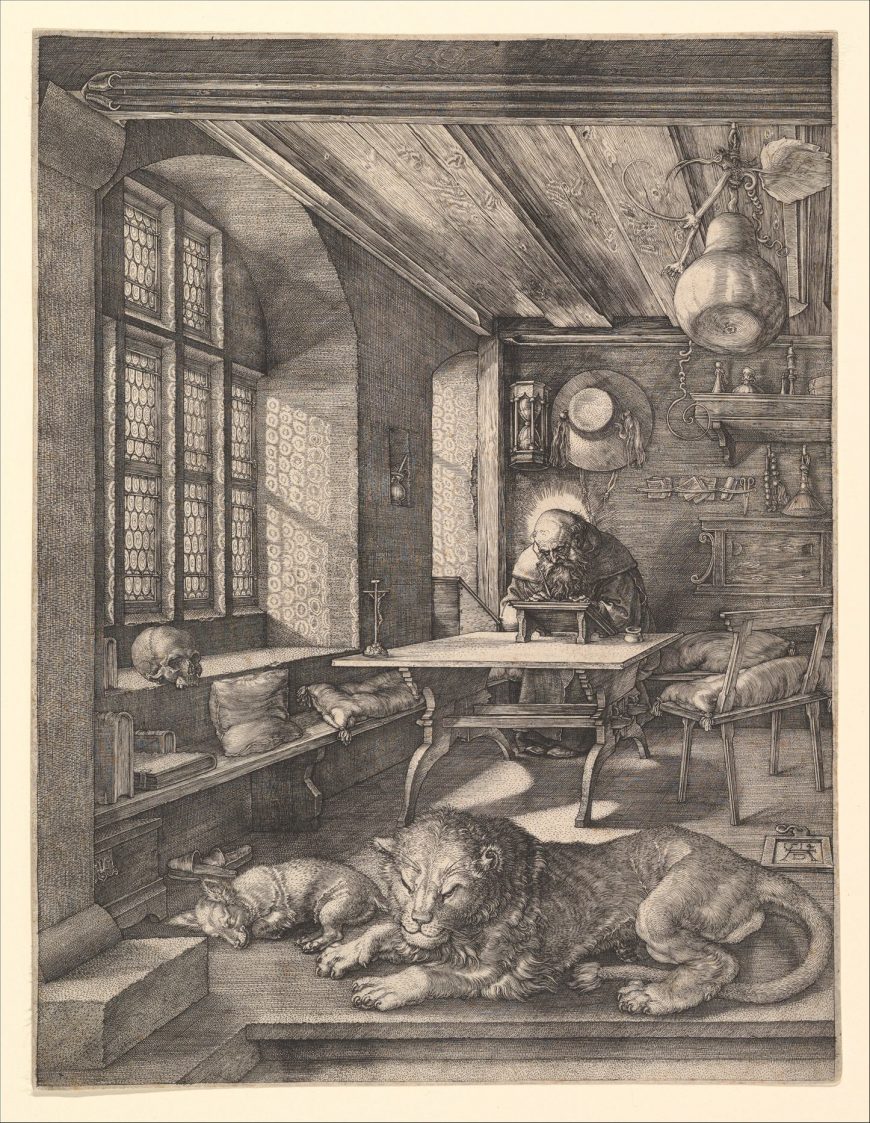

Albrecht Dürer, Saint Jerome in His Study, 1514, engraving, 24.6 x 18.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Order and confusion

If we compare the Melencolia to another of Dürer ’s master engravings, Saint Jerome in his Study, the chaos of Melancholy’s predicament comes into high relief. Jerome’s well appointed study glows with light, peace and calm. The saint works in the pleasant warmth of his study on his translation of the Bible from the original languages into Latin. Objects are orderly, though not rigidly so. The saint’s work is meditative rather than burdensome. He is unhurried—indeed the skull and hourglass, reminders of death and the passage of time—create no urgency or fear. Jerome has come to accept mortality and without fuss or worry, and he occupies himself exclusively with the matter at hand.

Compare the order of Jerome’s study to the scattered tools and scattered mind of Melencolia. Space itself is thrown into confusion. The polyhedron in the center of the composition turns the picture into a parody of a neatly organized Renaissance picture constructed according to the laws of one-point linear perspective. The polyhedron conceals the horizon, the starting point for linear perspective, a subject Dürer wrote about and used with aplomb. Rather than tidy orthogonals converging in vanishing point, the lines implied by the edges of the polyhedron zoom in all directions like scattering mercury.

One can imagine Melencolia tripping should she try to stand up because the space itself is in turmoil. Jerome’s contented lion and Melencolia’s neglected dog exemplify the contrast of productive calm and agitated disfunction. (Legend says that Jerome plucked a thorn from the lion’s paw and the he became Jerome’s trusty companion forever after.)

Melancholy and artists

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait or Portrait of the Artist Holding a Thistle, oil on parchment pasted on canvas, 56 x 44 cm (Louvre)

Melencolia is a flagship picture for Renaissance melancholy, a temperament that was increasingly tied to creativity and the construction of the artistic personality. During this period, Melancholy was divided up into three types; the Roman number I in this print likely refers to the category associated with artists.

While melancholy was seen purely as illness in the Middle Ages, the result of too much black bile, Renaissance thinkers began to see it as a badge of honor—the mark and burden of genius. This evolving notion of melancholy and its implications for the “artistic temperament” are evident in Dürer’s growth as an artist. His early self-portrait of 1494 bears the inscription “My affairs must go as ordained on high” (“1493 (D.H.); MIN SACH DIE, GAT ALS ES OBEN SCHTAT”).

This phrase, emphasizing fate and duty, perfectly expresses the late Gothic mentality of fulfilling divine and parental obligations rather than seeking fulfillment as an individual person. Individuality becomes particularly poignant for Dürer after his encounter with the Italian Renaissance in Italy.

Dürer’s diaries tell of his fascination not only with Italian art but with the status of the Italian artist. Italian artists were conceded expressive identities and rewarded with status and regard as intellectuals, while in Germany artists often remained respectable but anonymous artisans.

Additional resources:

Dürer, Melencolia at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dürer, St. Jerome in his Study at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dürer, Self-Portrait of the Artist Holding a Thistle at the Louvre