The Ancient Near East: The cradle of civilization?

Read Now >Chapter 7

Rethinking approaches to the art of the Ancient Near East until c. 600 B.C.E.

The Ram in a Thicket is made of precious materials—many of which were the result of long-distance trade. The ram’s head and legs are covered in gold leaf, its ears are copper-alloy (now green), its twisted horns and the fleece on its shoulders are of lapis lazuli, and its body fleece is made of white shell. Materials came from Afghanistan (lapis lazuli), the Persian Gulf (copper), and Turkey (gold and silver). Ram in a Thicket, c. 2600–2400 B.C.E., gold, lapis lazuli, silver, shell, bitumen, copper alloy, and red limestone, from Tomb PG 1237, Royal Tombs of Ur, southern Iraq, 45.7 x 30.48 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Enormous cities. Writing. Massive temples that stretched upwards to the sky. Long-distance trade. Developments that characterize the earliest states and empires of the Ancient Near East still enthrall us today. The art and architecture of the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Akkadians (from what is known as Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers), as well as Assyrian cultures from the 6th to the 1st millennium B.C.E. are often the focus, but these were inextricably tied to the greater region, including that of the ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Hittites, Mitanni, and Persians (also called the Achaemenids).

Map of the ancient Near East (underlying map © Google)

All of this is called the Ancient Near East, so called “near” because it is nearer to Europe (“the West“) than East and Southeast Asia, such as China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia, and Vietnam. This label is, plainly, Eurocentric, and dates to the 18th century and the European categorization and organization of the rich eastern trade lands. We might ask whether we should still use the term “Near East,” given how embedded it is in the colonial past—when European countries, such as England, France, Belgium, and Germany held huge swaths of land on the continents of Asia and Africa in order to systematically and violently extract valuable raw materials and labor, the fruits of which flowed back to colonial owners and nations while leaving colonized lands poor and politically volatile.

This tablet contains both a cuneiform inscription and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. Babylon is shown in the centre (the rectangle in the top half of the circle), and Assyria, Elam, and other places are also named. Map of the World, Late Babylonian, c. 500 B.C.E., clay, findspot: Abu Habba, 12.2 x 8.c cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

If you take any introductory course on art history, the art of the Ancient Near East will often be taught at the beginning and comprise several modules. It has become an important part of the art-historical canon for many reasons, including:

- The Ancient Near East is a part of the world where we find all the hallmarks of civilization—a collection of circumstances and practices, typically defined by urban living, craft specialization, a spectrum of wealth, from rich to poor, some form of government and laws or social organization, a written language, and monumental architecture.

- The art of the Ancient Near East illustrates some of the earliest, grandest, and most sweeping military conquests in world history.

- The history of the Ancient Near East is inextricably linked to to the stories and characters of the Bible, as well as their visual representation. Many of these stories have been a near constant subject matter of historians and art historians since the 19th century.

- Many Europeans have linked their cultural heritage to the history of the Ancient Near East for centuries.

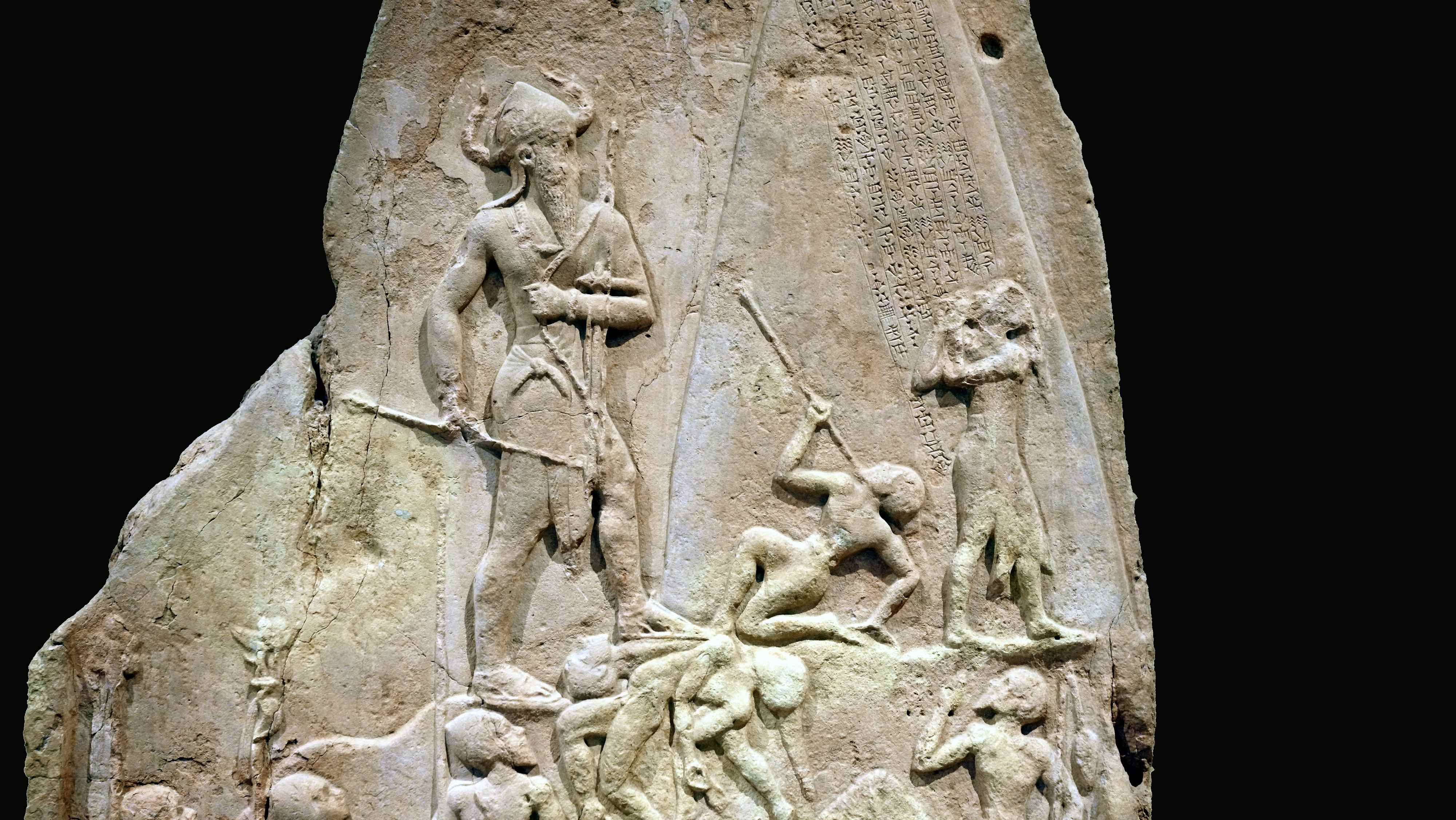

Naram-Sin leads his victorious army up a mountain, as vanquished Lullubi people fall before him. Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, 2254–2218 B.C.E., pink limestone, Akkadian (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Alongside these reasons one might add that we study the art and architecture of the Ancient Near East because it is spectacularly beautiful, astonishingly sophisticated (especially for such an early era), and at the same time emotional and human. However, a lot of what we say about Ancient Near Eastern art is rooted in outdated ideas or perspectives that need to be rethought and replaced with newer questions that have only begun to be explored. Early cities, for instance, also arose in places like the Indus Valley and ancient China (among others). This chapter seeks to highlight some of these outdated perspectives and to point to new areas of study.

Architecture: Power for Gods and Men

A general view of the Uruk archaeological site at Warka in Iraq

In the 4th millennium B.C.E. (c. 3200–3000 B.C.E.), Uruk in Mesopotamia was a city with a population of some 40,000 residents and another 80–90,000 working the fields in the environs. It was by far the greatest urban locus in the world at that time. The sheer power of Uruk’s agricultural wealth supported a larger population and afforded greater trade, all of which led to building on a monumental scale. Uruk was not alone; many of the city-states in the Ancient Near East had enormous buildings commissioned by the priestly class who controlled the agricultural surplus. This was a theocratic society—ruled by the priestly elite. Part of the power of this elite was their prominent representation in art. These, together with images of gods, were powerful symbols of power over vast groups of people.

To stand atop Uruk’s Ziggurat, at such a height, would convince anyone of rulers’ and priests’ god-like powers and prestige. White Temple and its Ziggurat, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E., Sumerian, mud brick, Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq)

The architecture of the Ancient Near East is among the first in the world to aim for monumental scale. Monumental architecture works in two ways: first, as something to look at in wonder because of its massive size and how it makes the viewer feel small next to it. Second, monumental architecture is powerful human-made topography, like building your own mountain to stand on top of it. In a region like southern Mesopotamia that is flat and marshy, to erect a massive structure, reaching skyward, mountain-like, would have seemed an accomplishment only a god could ordain. An example of just such a structure is the White Temple and Ziggurat at Uruk.

Not only did the White Temple and Ziggurat rise from the surrounding plane like a human-made peak but climbing the carefully constructed stairs to the elevated plateau and looking down offered a brand new sense of geographical and human domination. Only a god and his theocratic colleagues on earth could see to the creation of something so massive and this power would have been intensely felt by those holding that high ground. As a layperson, confronting that power would be humbling.

Part of a series which decorated the walls of a room in the palace of King Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 B.C.E.). The Assyrian soldiers continue the attack on Lachish. They carry away a throne, a chariot and other goods from the palace of the governor of the city. In front and below them some of the people of Lachish, carrying what goods they can salvage, move through a rocky landscape studded with vines, fig and perhaps olive trees. Sennacherib records that as a result of the whole campaign he deported 200,150 people. This was standard Assyrian policy, and was adopted by the Babylonians, the next ruling empire. The Siege and Capture of the City of Lachish in 701 B.C.E., South-West Palace of Sennacherib, Nineveh, northern Iraq, Neo-Assyrian, c. 700–681 B.C.E., alabaster, 182.88 x 193.04 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

A similar kind of humbling power was employed in the interior spaces of Ancient Near Eastern elite architecture and the best example of this can be found in the well-preserved interior relief sculptures of Neo-Assyrian palaces built for rulers. The inner rooms of these structures, especially those which would be seen by visitors, were decorated with richly carved and vividly painted scenes of warfare, brutal subjugation of enemies, the extraction of resources from vanquished lands, and the erection of monumental structures. All of these scenes glorified the theocratic kings of Neo-Assyria and were intended to make visitors feel weak and vulnerable.

Lamassu (winged human-headed bulls possibly lamassu or shedu) from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (now Khorsabad, Iraq), Neo-Assyrian, c. 720-705 B.C.E., gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the king’s theocratic role, not only did he act as an intercessor between the gods and men but he could harness the power of mythoreligious characters such as Lamassu—hybrid man, bird, bull, or lion creatures. Images of Lamassu were created at a colossal scale and set in doorways leading to public spaces in palaces, through which visitors were compelled to pass. These would have had an awe-inspiring effect on the viewer. As with the White Temple and Ziggurat, the experience of confronting the Lamassu, the fear and astonishment it elicited, was critical to its function and power.

Watch a video and read an essay about architecture

White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk: A massive platform and temple that suggest the power of those in control.

Read Now >

Perforated Relief of Ur-Nanshe: The chief priest and king displayed his piety and power by building a temple.

Read Now >

Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II: Colossal sculptures intended to intimidate those who encountered them.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The Representation of Warfare

View of the side featuring images of war. The Standard of Ur, 2600–2400 B.C.E., shell, red limestone, lapis lazuli, and bitumen (original wood no longer exists), 21.59 x 49.53 x 12 cm (British Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When the sites of the Ancient Near East were explored at the end of the 19th and early 20th century by English, French and German archaeologists, the objects, languages, and images found were entirely new to the modern world. However, one familiar theme was seen in these remains again and again: the representation of warfare—such as we see on objects like the Sumerian Standard of Ur or the Akkadian Victory Stele of Naram-Sin. Various examples of warfare can also be found on later Neo-Assyrian palace reliefs, for instance, those showing the battle of Til Tuba.

Wall panel depicting the Battle of Til-Tuba (Battle of the River Ulai) between the Assyrians and Elamites. In the lower register, Assyrians attack from the left. The two armies are clearly distinguished by their equipment and formation. Neo-Assyrian, 660 B.C.E.–650 B.C.E., gypsum, from the South West Palace at Nineveh, Iraq, 204 x 175 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Across these examples and countless others, the representation of warfare, defeat, subjugation of the enemy, seizing of territory and resources are ritualized and presented as one of the supreme expressions of empire. Recent scholarship argues that the ritualization of war and images of violence constituted part of a magical technology of warfare that not only justified the underlying processes of war but presented a kind of control of its chaos. Only the king, aided by the gods, could wage such violence on such a massive scale; the huge numbers of soldiers, marching in tandem and formation, and the horrifying destruction they wrought, was seen as a sort of magical terror only unleashed by holy, kingly ritual.

By presenting the Sumerian, Akkadian, or Assyrian king as not only a warrior but master of the violence and spoils of war in his art, he is presented as all powerful and all controlling. This is nothing short of the origin of the public, political war monument—permeated with the propaganda of the victor.

Illustrating and monumentalizing war between nation states grew in popularity and political currency in the West in the 19th and 20th century, and often featured images of violent chaotic battle fields, fallen soldiers, and subjugated enemies (such as Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People)—all strikingly similar to examples in the Ancient Near East. We can imagine that the visual ideology of ritualized war found in the archaeological remains of so many Ancient Near Eastern sites contributed to these modern images—naturalizing and universalizing the violent actions of the English and Germans busy excavating at Ur and Babylon.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin (detail), 2254–2218 B.C.E., pink limestone, Akkadian (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Of course, the central focal point in the ancient images of war are the victorious armies and kings. But, at the bottom of these scenes, literally and figuratively, we find some of the earliest images of the tortured and trammeled. These details of contorted dead and dismembered bodies were part of the imaging of violence mentioned above, but they also stand as witness to dominated peoples, often missing in the annals of history, visual or written. In our own era of international humanitarian law (especially within the context of armed conflict) these fallen people are particularly poignant and remind us of our hard-won rights.

Watch videos about the representation of warfare

Standard of Ur: The representation of warfare decorates one entire side of this Sumerian object.

Read Now >

/3 Completed

Writing, Women, and Sexuality

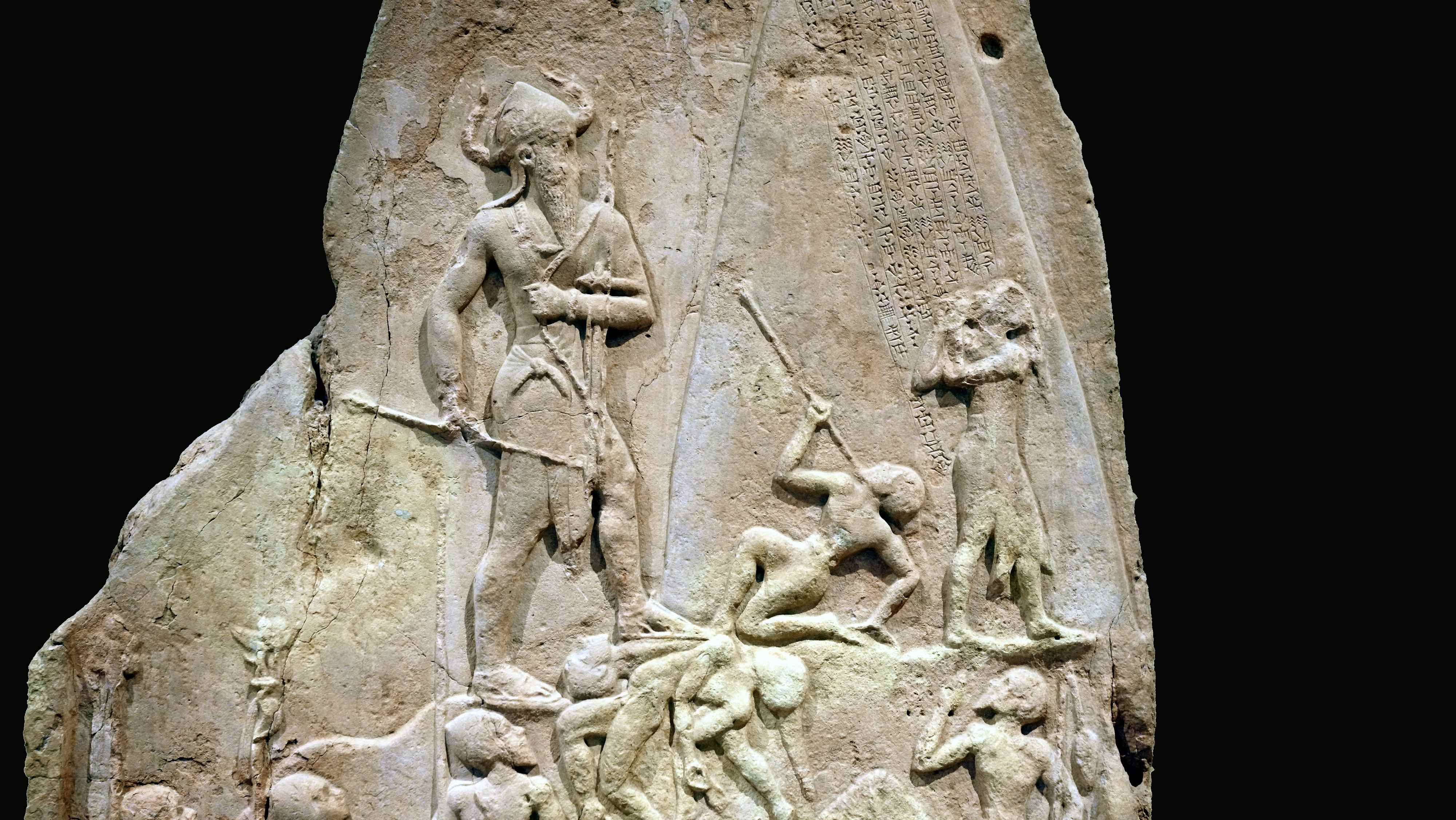

Cuneiform cylinder with inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II describing the construction of the outer city wall of Babylon, Neo-Babylonian, c. 604–562 B.C.E., clay, 6.7 × 12.35 × 7.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

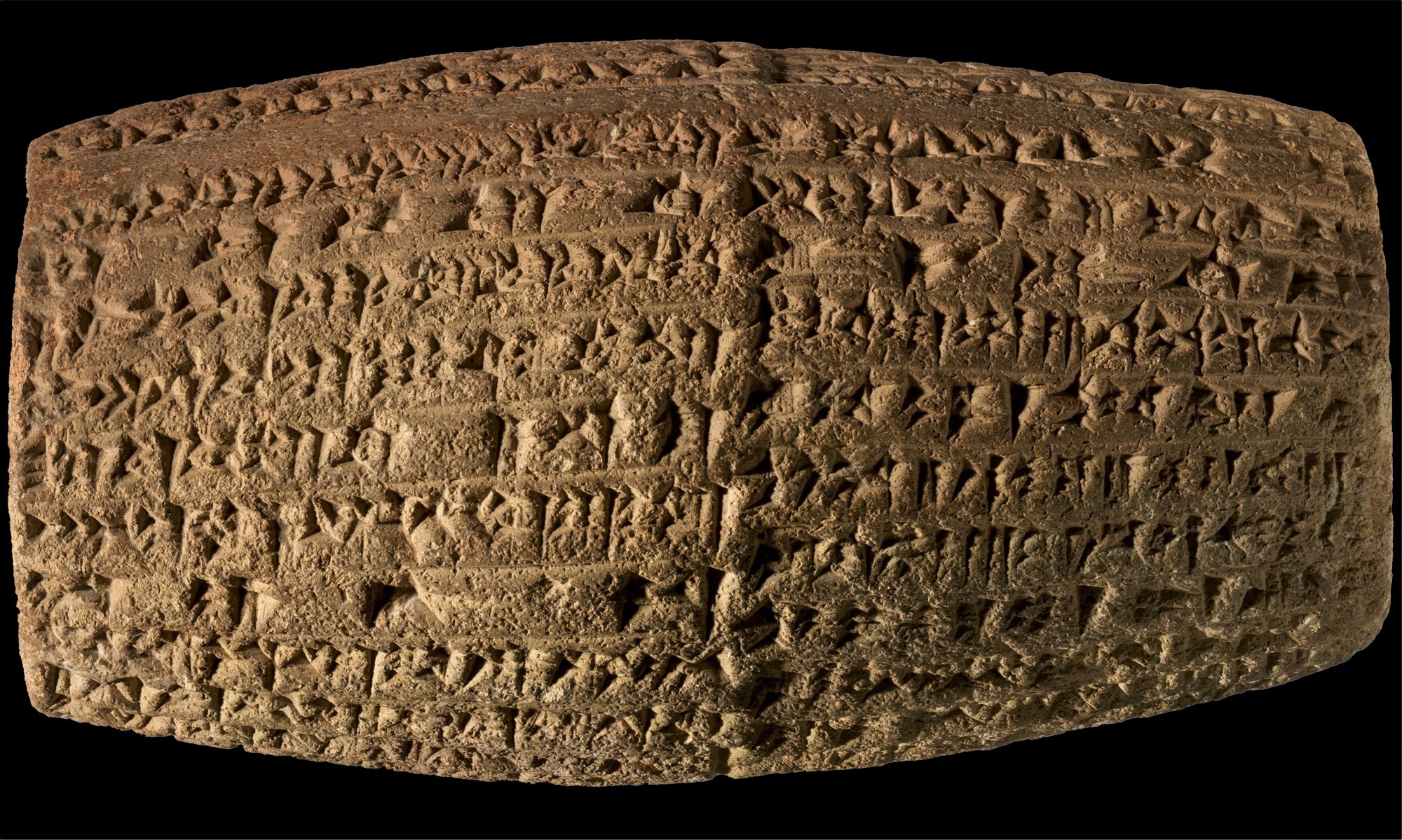

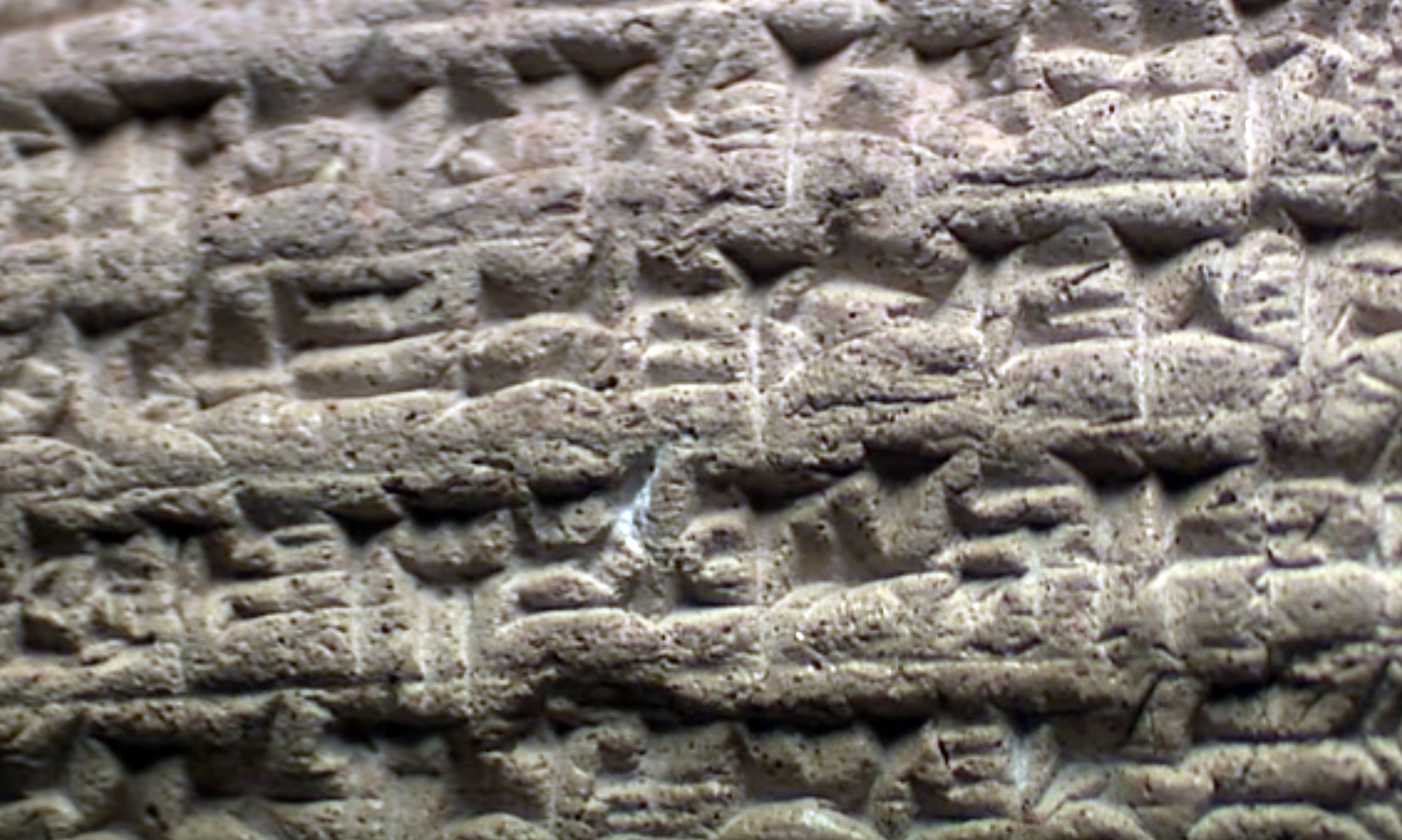

The circumstance of women in the Ancient Near East, as revealed through art and texts, is somewhat incongruous. Cuneiform tablets (clay slabs with writing on them), common among the remains of the era, are among the most important evidence of Ancient Near Eastern culture, not only an essential primary resource for the study of politics and economy but also a wellspring of first-person voice and lived narrative.

Learn about writing and cylinder seals

/2 Completed

Among these documents we can read about thousands of individual women and discover that elite women acted in all the roles that men did, although in smaller numbers: they corresponded with men, kings, and each other; bought, sold, and loaned land and other critical commodities; borrowed and guaranteed debts; acted as witness in legal proceedings; participated in trading ventures, sometimes far from home and were frequent users of cylinder seals ( a small pierced object, like a long round bead, carved in reverse and hung on strings of fiber or leather. When a signature was required, the seal was taken out and rolled on the pliable clay document, leaving behind the positive impression of the reverse images carved into it.)

.

Cylinder seal, owned by a woman named Šaša, Akkadian, calcite, 39 x 22 mm, from Khafajeh, Iraq (Oriental Institute, University of Chicago)

Tens of thousands of cylinder seals were made and used in the Ancient Near East to minutely and intimately tell stories about men and women, priestesses and traders, kings and goddesses through images and writing understood and valued by all who saw them.

Scene of agricultural work and swimmers in river, c. 645 B.C.E., Assyrian, relief, from Royal Palaces of Nineveh (The British Museum)

Non-elite women are here too, part of a large work-force for physically demanding labor such as weaving, flour grinding, boat towing, and reed cutting. We find out about these laborers mostly through text, though there are some rare images such as those from the Assyrian palace at Nineveh that includes agricultural workers.

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi, basalt, Babylonian, 1792–1750 B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Most cuneiform comes down to us on clay tablets but some cuneiform inscriptions have been found engraved on stone statues, reliefs, or stelae. Probably the most famous example of a cuneiform engraved stele is that of Hammurabi.

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi (detail), basalt, Babylonian, 1792–1750 B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The stele of Hammurabi, also called the law code of Hammurabi, dates to the 18th century B.C.E. and contains laws which, taken together, represent one of the earliest legal codes. It is a nearly encyclopedic compendium of law, known through multiple copies, and is particularly sympathetic to workers (for instance, a sort of minimum wage is included in it) and establishes a high bar of proof of crime, put upon the accuser, another legal mechanism which aids non-elites.

Some laws that relate to women

129. If the wife of a man is caught lying with another man, they shall bind them and throw them into the water. If the husband of the woman wishes to spare his wife, then the king shall spare his servant.

130. If a man has ravished another’s betrothed wife, who is a virgin, while still living in her father’s house, and has been caught in the act, that man shall be put to death; the woman shall go free.

131. If a man has accused his wife but she has not been caught lying with another man, she shall take an oath in the name of god and return to her house.

138. If a man wishes to divorce his wife who has not borne him children, he shall give her money to the amount of her marriage price and he shall make good to her the dowry which she brought from her father’s house and then he may divorce her.

141. If the wife of a man who is living in her husband’s house, has persisted in going out, has acted the fool, has waster her house, has belittled her husband, he shall prosecute her. If her husband has said, “I divorce her,” she shall go her way; he shall give her nothing as her price of divorce. If her husband has said “I will not divorce her” he may take another woman to wife; the wife shall live as a slave in her husband’s house.

142. If a woman has hated her husband and has said, “You shall not possess me,: her past shall be inquired into, as to what she lacks. If she has been discreet, and has no vice, and her husband has gone out, and has greatly belittled her; that woman has not blame, she shall take her marriage portion and go off to her father’s house.

143. If she has not been discreet, has gone out, ruined her house, belittled her husband, she shall be drowned.

150. If a man has presented a field, garden, house, or goods to his wife, has granted her a deed of gift, her children, after her husband’s death, shall not dispute her right; the mother shall leave it after her death to that one of her children whom she loves best. She shall not leave it to an outsider.

From the Code of Hammurabi

In this law code, we find that women enjoyed a surprising measure of rights. Marriage and monogamy were central to female legal frameworks and within this women were treated relatively well. For instance, if stipulated in a marriage contract, women were free of their husband’s premarital debts. Women could inherit property from their husbands’ estates and could own their own property outright. Divorce was allowed and, when initiated by the husband, the wife’s dowry had to be returned and, in the case of children, half the husband’s estate had to be given to the wife. However, when a woman initiated divorce (a remarkable right included in the law code) her character was put on trial and, unless she was found above reproach, she would be put to death. Moreover, crimes against women such as rape, robbery, or perjury resulted in death of the perpetrator, showing the value of women, married or otherwise, in society.

Standing worshippers, 2750–2600 B.C.E., Early Dynastic period II (Sumerian), excavated at Tell Asmar (ancient Eshnunna), Iraq, alabaster (gypsum), shell, black limestone; 11-5/8 inches (29.5 cm) high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

However, despite this clear evidence of the important economic, social, and political roles that women played, there are few representations of them (besides divine women and priestesses) in Ancient Near Eastern art. Indeed, some elite women—mostly priestesses—are shown especially on cylinder seals, and elite female worshipers (possibly priestesses) were found among the figurines discovered at the Square Temple at Eshnunna.

The high priestess Enheduanna is shown performing a ritual to the moon goddess Nanna. Relief of Enheduanna, Old Akkadian Period, c. 2340–2200 B.C.E., limestone and calcite, 25 cm diameter, from Ur, Iraq, found in a chamber of the Larsa temple of Nin-Gal (the Gig-par-ku) (Penn Museum)

And, one individual woman’s representation survives, that of Enheduanna, on a limestone disk which bears her name, found at Ur dating to around 2200 B.C.E. Enheduanna was a high priestess of the moon goddess Nanna and is shown on the disk performing a ritual to her. Enheduanna was also the daughter of Sargon, the founder of the Akkadian empire, no doubt a major factor in her prominence. But what she is really known for is her poetry. Enheduana was the author of several temple hymns which were so highly regarded that they were copied and recopied for several hundred years. Enheduanna is recognized as the first author—of any gender—we know.

from The Hymn to Inanna

Translation by Jane Hirshfield. Women in Praise of the Sacred, edited by Jane Hirshfield (HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 1994).

Interestingly, there would appear to be a “middle” class of woman in the Ancient Near East, those who were not part of the laboring or slave classes nor the elite, and who were not under the patriarchal control of either a father or husband. These women, called harimtu, are well attested to in the Akkadian empire, and were neither married nor widowed. Some were rich, some poor, and all appear to have been rather independent. Harimtu is a label also quite commonly interpreted as sex worker. There is a lively debate among philologists and historians as to the precise role and status of harimtu but it would appear that at least some were engaged in sex work associated with temples; there was an association between sex and the divine, so there were women at the temples who had sex with congregants as a type of prayer or pious act. Indeed, if harimtu were sex workers, then images of them likely remain among the many examples of erotic terracotta plaques.

Fired clay plaque showing a woman sipping beer through a straw from a jar resting on the ground while being penetrated from the rear by a nude male. Old Babylonian, c. 1800 B.C.E., fired clay, from South Iraq, 8.9 x 7.2 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Images of sex, both heterosexual and homosexual, were not uncommon in the Ancient Near East. Through reading sacred texts it becomes clear that sexual desire was considered a divine force and because of this prayers to bring on male and female sexual desire and satisfaction are common. It is thought that these erotic plaques therefore had some sort of cultic function or at least participated in aspirations of sexual and spiritual fulfillment.

Watch videos about women, writing, and sexuality

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi: An early legal code that tells us a great deal about women in the Ancient Near East.

Read Now >

Standing Worshippers from Tell Asmar: While the standing male figure gets a lot attention, the figures also included women.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Questioning the Cradle of Civilization

The Cradle of Civilization—this phrase is often used to refer to Mesopotamia. But is it time we complicated that idea more?

The search for the origin of things has been a preoccupation throughout all of human history. Whether through religion, science, or history, we strive to know and understand where things come from because we believe that those origins are meaningful. The origin of civilization is no different. Civilization is understood as a collection of circumstances and practices, typically defined by urban living, a spectrum of wealth, from rich to poor, some form of government or social organization, monumental architecture, craft specialization, and a written language. According to what we know archaeologically, all these circumstances and practices can indeed be found for the first time at Uruk in Southern Mesopotamia at the end of the 5th millennium.

Tell Brak, Syria, area TW, showing the 5th–6th century millennium B.C.E. levels (photo: Bertramz, CC BY 3.0)

However, this first-place prize is only narrowly won. Evidence from sites such as Tell Brak in modern Syria suggest that cities and writing may have developed in northern Mesopotamia at the same time or even before those in the south. At roughly the same time, in Egypt, sites of the Predynastic period (such as Abydos and Naqada), also appear to have all the characteristics of civilization.

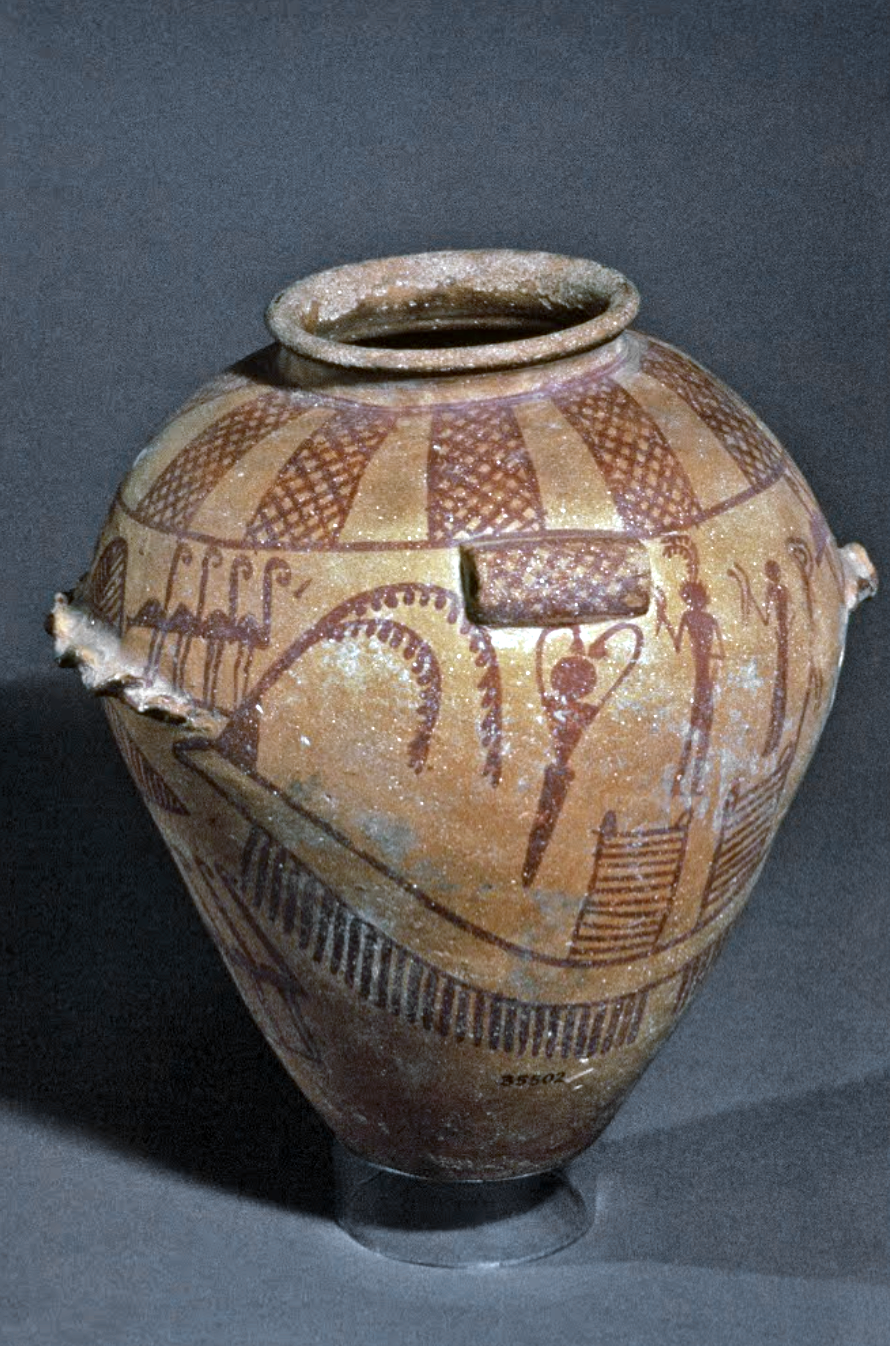

Decorated jar, c. 3500 B.C.E., predynastic period (Naqada II), pottery, found in a tomb in el-Amra, Egypt, 22.5 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Therefore, it looks as if the beginning of civilization was a phenomenon that occurred at the same time very broadly, from southern Mesopotamia to the edges of the northern Levant to the northeast coast of Africa.

Bushel with ibex motifs, 4200–3500 B.C.E., painted terra-cotta, 28.90 x 16.40 cm, necropolis, Susa I period, from the acropolis mound, Susa, Iran (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the Near East, the site of Susa was a center of spectacular pottery production, such as we see on a bushel with ibex motifs.

Newgrange, Brú na Bóinne Complex, c. 3200 B.C.E., Republic of Ireland

Or, further afield, in the Republic of Ireland at the Brú na Bóinne Complex of monumental structures or Stonehenge in England.

Caral-Supe cultural developed c. 3000–1800 B.C.E., and the city of Caral is currently considered the oldest in the Americas. Caral-Supe, in the Supe Valley, Peru (photo: Xauxa, CC BY 2.5)

And then of course, if we look even further beyond, in places like China, India, and Peru, things become more complicated. If this is the case, it is harder to place the “cradle” so singularly.

We might at the same time think about why certain characteristics make an early site “civilized” and others do not. The concept of civilization was developed as part of 18th-century French, British, and German Enlightenment philosophy focused on the pursuit of happiness, knowledge and human freedoms—and ultimately was used to justify slavery. Enlightenment philosophy taught that cultures which had achieved urbanism, stratified society in governmental structures, and written languages—what was believed to be the ultimate expression of human endeavor: enlightenment—were at the top of the evolutionary scale; those which had not were at the bottom and therefore, logically, less developed and, ultimately, servile to the higher orders.

This judgment and ordering of cultures remained largely unchallenged through the 18th, 19th, and even early 20th century, the period in which many sites in the Near East were excavated. Therefore, the cultures of the Ancient Near East, by this logic, were deemed “civilized.” However, there was another factor which automatically elevated ancient Near Eastern cultures: their connections to biblical narratives. The lands of the Ancient Near East held the birthplace of both Judaism and Christianity; sites such as Jericho, Nazareth, Jerusalem, Babylon, Nineveh, Tyre, the homes of Old Testament Kings and Jesus himself. The ancient remains of these sites, by association with Christianity, the dominant faith of the West from the Renaissance until the 20th century and intimately connected with concepts of European superiority, were regarded as “civilized.”

Today such racial approaches to history are strongly rejected and the ordering of cultures as more or less civilized is also swiftly losing value. Once we are no longer preoccupied with compiling lists of cultural traits we can instead focus on unique cultural production, and the list of early “cradles” of civilization in the 4th millennium expands.

Read essays and watch videos that challenge where we locate the "cradle of civilization"

Bushel with ibex motifs: How does this object challenge our ideas about the Ancient Near East?

Read Now >

Seal from the Indus Valley: Sites in South and East Asia also challenge where we locate the cradle of civilization

Read Now >

/4 Completed

So, although re-evaluating the idea of what culture gets the title “the cradle of civilization” might knock southern Mesopotamia off the pedestal it has so long occupied, it offers us an opportunity to appreciate the importance of other contemporary cultural achievements and realize that we gain more by opening up our view of the 4th millennium. By focusing on quieter voices, those of the vanquished and that of women, by rethinking the idea of the “cradle of civilization,” and by de-emphasizing imperial narratives of the Ancient Near East, a fuller picture of the art of the era emerges.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did Ancient Near Eastern temples and palaces reflect on the rulers who built them?

What does Ancient Near Eastern Art and writing tell us about women of the era?

How was war represented in Ancient Near Eastern Art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did Ancient Near Eastern temples and palaces reflect on the rulers who built them?

What does Ancient Near Eastern Art and writing tell us about women of the era?

How was war represented in Ancient Near Eastern Art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamia

cuneiform

stele or stelae

hierarchic scale

lamassu

ziggurat

theocracy

cylinder seal

relief

harimtu

register

monolith

Learn more

Learn more about Ancient Near Eastern cultures on Smarthistory.