Winged, human-headed bulls served as guardians of the city and its palace—walking by, they almost seem to move.

Lamassu (winged human-headed bulls possibly lamassu or shedu) from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (now Khorsabad, Iraq), Neo-Assyrian, c. 720–705 B.C.E., gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m (Musée du Louvre, Paris). These sculptures were excavated by P.-E. Botta in 1843–44. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] Ancient Mesopotamia’s often credited as the cradle of civilization, that is, the place where farming and cities began. It makes it seem so peaceful, but this was anything but the case. In fact, it was a series of civilizations that conquered each other.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:20] We’re in a room in the Louvre filled with sculpture from the Assyrians, who controlled the ancient Near East from about 1000 B.C.E. to around 500 B.C.E.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] These sculptures, in particular, come from the Palace of Sargon II and were carved at the height of Assyrian civilization in the 8th century B.C.E.

Dr. Harris: [0:41] This is modern-day Khorsabad.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] In Iraq.

Dr. Harris: [0:44] Various Assyrian kings established palaces at different cities. There were palaces at Nimrud and Assur before this, and after, there’ll be a palace at Nineveh. These sculptures come from an excavation from modern-day Khorsabad.

Dr. Zucker: [1:00] The most impressive sculptures that survive are the guardian figures that protected the city’s gates and protected the gates of the citadel itself, that is, the area within which were both the temple and the royal palace.

Dr. Harris: [1:14] At each of these various gates, there were guardian figures that were winged bulls with the heads of men.

Dr. Zucker: [1:20] We think they’re called Lamassu.

Dr. Harris: [1:22] As figures that stood at gateways, they make sense. They’re fearsome. They look powerful. They could also be an expression of the power of the Assyrian king.

Dr. Zucker: [1:33] They are enormous, but even they would have been dwarfed by the architecture. They would have stood between huge arches. In fact, they had some structural purpose.

[1:42] It’s interesting to note that each of these Lamassu are carved out of a monolithic stone, that is, there are no cuts here. These are single pieces of stone. In the ancient world, it was no small task to get these stones in place.

Dr. Harris: [1:56] Apparently, there were relief carvings in the palace that depicted moving these massive Lamassu into place. It’s important to remember that the Lamassu were the gateway figures. The walls of the palace were decorated with relief sculpture showing hunting scenes and other scenes indicating royal power.

Dr. Zucker: [2:15] This is a Lamassu that was a guardian for the exterior gate of the city. It’s in awfully good condition.

Dr. Harris: [2:21] My favorite part is the crown. It’s decorated with rosettes, and then double horns that come around toward the top center. Then, on top of that, a ring of feathers.

Dr. Zucker: [2:33] It’s really delicate for such a massive and powerful creature. The faces are extraordinary. First of all, at the top of the forehead, you can see incised wavy hair that comes just below the crown. Then you have a connected eyebrow.

Dr. Harris: [2:47] Then the ears are the ears of a bull that wear earrings.

Dr. Zucker: [2:51] Quite elaborate earrings.

Dr. Harris: [2:52] The whole form is so decorative.

Dr. Zucker: [2:55] There’s that marvelous, complex representation of the beard. You see little ringlets on the cheeks of the face. As the beard comes down, you see these spirals that turn downward and then are interrupted by a series of horizontal bands.

Dr. Harris: [3:10] The wings, too, form this lovely decorative pattern up the side of the animal and then across its back.

Dr. Zucker: [3:17] In fact, across the body itself, there are ringlets as well. We get a sense of the fur of the beast and under the creature and around the legs, you can see inscriptions in cuneiform.

Dr. Harris: [3:29] Some of which declare the power of the king.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] And damnation for those that would threaten the king’s work, that is, the citadel.

Dr. Harris: [3:35] What’s interesting, too, is that these were meant to be seen both from a frontal view and a profile view.

Dr. Zucker: [3:41] If you count up the number of legs, there’s one too many. There are five.

Dr. Harris: [3:45] Right, two from the front and four from the side. Of course, one of the front legs overlaps, so there are five legs.

Dr. Zucker: [3:52] What’s interesting is that when you look at the creature from the side, you see that it’s moving forward. When you look at it from the front, those two legs are static. The beast is stationary. Think about what this means for a guardian figure at a gate.

[4:05] As we approach, we see it still, watching us as we move. If we belong, if we’re friendly and we’re allowed to pass this gate, as we move through it, we see the animal itself move.

Dr. Harris: [4:17] Then we have this combination of these decorative forms that we’ve been talking about, with a sensitivity to the anatomy of this composite animal. His abdomen swells and his hindquarters move back. We can see the veins and muscles and bones in his leg.

Dr. Zucker: [4:34] There is this funny relationship between the naturalistic and the imagination of this culture.

Dr. Harris: [4:39] And the decorative. But all speaking to the power, the authority of the king and the fortifications of this palace and this city.

Dr. Zucker: [4:50] They are incredibly impressive. It would be impossible to approach the citadel without being awestruck by the power of this civilization.

[4:57] [music]

Map of the Assyrian empire at its greatest extent during the reign of Ashurbanipal, 668–c. 627 B.C.E. (map: © The Trustees of the British Museum, London). There were palaces at Kalhu (Nimrud), Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad), and Nineveh

Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II Khorsabad

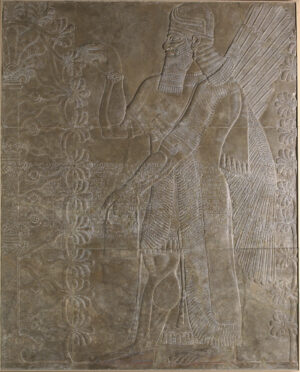

Human-headed genie watering sacred tree, 883–859 B.C.E., gypseous alabaster with traces of paint, 224.8 x 184.8 cm (Yale Art Gallery, New Haven)

The architecture and sculptural decorations of Neo-Assyrian palaces dating to the first half of the 1st millennium B.C.E. are not only unique in the Ancient Near East but exceptionally powerful and beautiful. Huge courtyards and halls led the visitor deeper and deeper into the king’s realm, revealing more and more complex sculptural programs along the progression. Images depicted the brutal destruction of enemy cities, the ruthless extraction of natural resources, the king hunting lions with a bow and arrow, and sacred spirits (winged men call genii) tending a tree of life.

Between these courtyards and halls, punctuating these scenes of power and prestige are massive pairs of doorway sculptures called Lamassu. The Lamassu are distinctive to Neo-Assyrian architectural sculpture (although the creatures which they represent have a long history in the Ancient Near East, dating to the Early Dynastic period) and several pairs of them survive to this day. The remains of more than 100 Lamassu have been identified at Neo-Assyrian palace sites. Because of their massive size and formidable form, since the discovery of Neo-Assyrian palaces in the 19th century, they have been a source of awe and fascination, even living on in art deco architecture of the 20th century.

A hybrid monster

A lamassu (also called a šedu, aladlammû or genii) is an apotropaic or protective hybrid monster with the bearded head of a mature mane, crown of a god, and the winged body of either a bull or lion. They are massive, up to 20 feet tall and weigh as much as 30–50 tons. Remarkably, each is carved from a single slab of limestone, gypsum alabaster, or breccia.

Winged human-headed bull (lamassu or shedu), 721–705 B.C.E. (reign of Sargon II, Neo-Assyrian Period, Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin, Assyria, Iraq), gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m, excavated by P.-E. Botta 1843–44 (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This pair at the Louvre is from the Palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad and dates from 720–705 B.C.E. and represents a winged bull with the bearded head of a man wearing a double horned crown. The face of the Lamassu is broad, with a strong nose and thick eyebrows which are double arched across his whole forehead. The massive beard is represented as thickly curled and braided, nearly doubling the size of the Lamassu’s face. His wide eyes look straight out over the head of the viewer, as if engaged in matters beyond the human realm. His crown, feather-topped, is decorated with rows of rosettes (a motif associated with divinity and possibly the goddess Ishtar) and set with a double-horned crown, marking the Lamassu as divine. His pointed bovine ears, ringed with gold hoops suspending beads, emerge from beneath the crown as well as long flowing locks which end in rows of tight curls giving a sense of buoyancy. The fur of the bull’s body is also richly curled, although in very organized straight rows which run along its breast, back, side and rear flank. Even the Lamassu’s tail is curled and braided.

Winged human-headed bull (lamassu or shedu), 721–705 B.C.E. (reign of Sargon II, Neo-Assyrian Period, Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin, Assyria, Iraq), gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m, excavated by P.-E. Botta 1843–44 (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Huge cloven feet

The huge cloven feet of the Lamassu show him both standing and walking, courtesy of the carving having five legs instead of four. This is to present a kind of split view: when one approaches the Lamassu from the front, they look as if they are standing still guarding the door, but when you pass between them, you see all four of their legs walking forward. This odd detail, which is not common to all Lamassu, is done for two reasons. Firstly, because as much of the bulk of the stone must be left intact as possible to help support the weight of arch of the doorway. To carve out the space around the legs of the Lamassu, which would make the fourth front leg visible while passing between them, would weaken the arched doorway. The other reason is to ensure that no matter from what angle one sees the Lamassu, it looks formidable. The legs of the Lamassu are not only massive but very muscular, giving a clear sense of the power of this hybrid creature. Added to this complex sculptural representation, we must recall, was color. Several examples of Neo-Assyrian sculpture have been examined for the remains of their pigment and have been found to still hold microscopic traces of white calcium carbonate and calcium sulfate, bone black and charcoal, hematite red, cinnabar red, and cobalt blue.

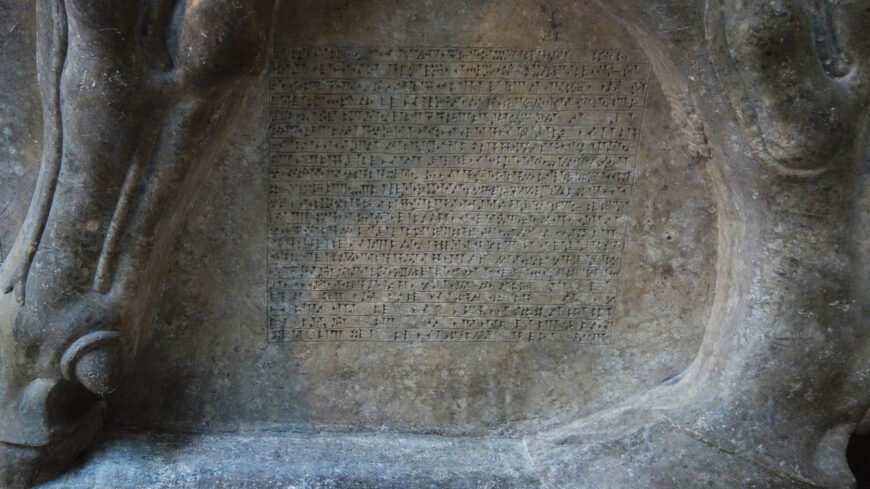

Standard inscription in cuneiform (detail), Winged human-headed bull (lamassu or shedu), 721–705 B.C.E. (reign of Sargon II, Neo-Assyrian Period, Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin, Assyria, Iraq), gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m, excavated by P.-E. Botta 1843–44 (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On two panels between the hind legs of the Lamassu is a long inscription in cuneiform called the standard inscription. This is a statement listing the victories and virtues of King Sargon, his piety and the ways in which the gods have favored him. It also threatens a curse on whomever should seek to harm his palace. This kind of standard inscription is common on many Neo-Assyrian wall reliefs and Lamassu and can be seen as a scriptural representation of the images they are layered upon.

Winged human-headed bull (lamassu or shedu), 721–705 B.C.E. (reign of Sargon II, Neo-Assyrian Period, Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin, Assyria, Iraq), gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m, excavated by P.-E. Botta 1843–44 (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Awe-inspiring

What is so awe-inspiring about these sculptures is not only their size but the powerful clarity with which they are sculpted and the terrifyingly precise repetition of forms. Curls and horns are incised with deep, powerful cuts in high relief and smoothed into sharp readability. The strict linear, mathematical arrangement of feathers, curls, and rosettes gives the Lamassu a perfected restraint, humanizing the frightening and chaotic hybridity. Possibly the most terrifying and impressive aspect of the carving of the Lamassu, however, is the precision of its sculptural repetition. Dating to an era much before “cut and paste” or any sort of mechanical reproductive methods in sculpture, we find the craftsmen of the Lamassu were masters of scrupulous and endlessly repetitive imitation.

Winged human-headed bull (lamassu or shedu), 721–705 B.C.E. (reign of Sargon II, Neo-Assyrian Period, Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin, Assyria, Iraq), gypseous alabaster, 4.20 x 4.36 x 0.97 m, excavated by P.-E. Botta 1843–44 (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Backstory

The lamassu in museums today (including the Louvre, shown in our video, as well the British Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, and others) came from various ancient Assyrian sites located in modern-day Iraq. They were moved to their current institutional homes by archaeologists who excavated these sites in the mid-19th century. However, many ancient Assyrian cities and palaces—and their gates, with intact lamassu figures and other sculptures—remain as important archaeological sites in their original locations in Iraq.

In 2015, a chilling video circulated online, showed people associated with ISIS destroying ancient artifacts in both the museum in Mosul, Iraq and at the nearby ancient archaeological site of ancient Nineveh. Their targets included the lamassu figures that stood at one of the many ceremonial gates to this important ancient Assyrian city. Scholars believe that this particular gate, which dates to the reign of Sennacherib around 700 B.C.E., was built to honor the god Nergal, an Assyrian god of war and plague who ruled over the underworld. Islamic State representatives claimed that these statues were “idols” that needed to be destroyed. The video features footage of men using jackhammers, drills, and sledgehammers to demolish the lamassu.

The Nergal gate is only one of many artifacts and sites that have been demolished or destroyed by ISIS over the past decade. Despite the existence of other examples in museums around the world, the permanent loss of these objects is a permanent loss to global cultural heritage and to the study of ancient Assyrian art and architecture.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee