One of a group buried in a temple almost 5,000 years ago, this statue’s job was to worship Abu—forever.

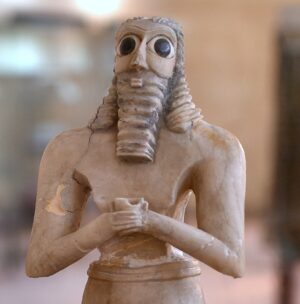

Standing Male Worshipper (votive figure), c. 2900-2600 B.C.E., from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), gypsum alabaster, shell, black limestone, bitumen, 11 5/8 x 5 1/8 x 3 7/8″ / 29.5 x 10 cm, Sumerian, Early Dynastic I-II (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

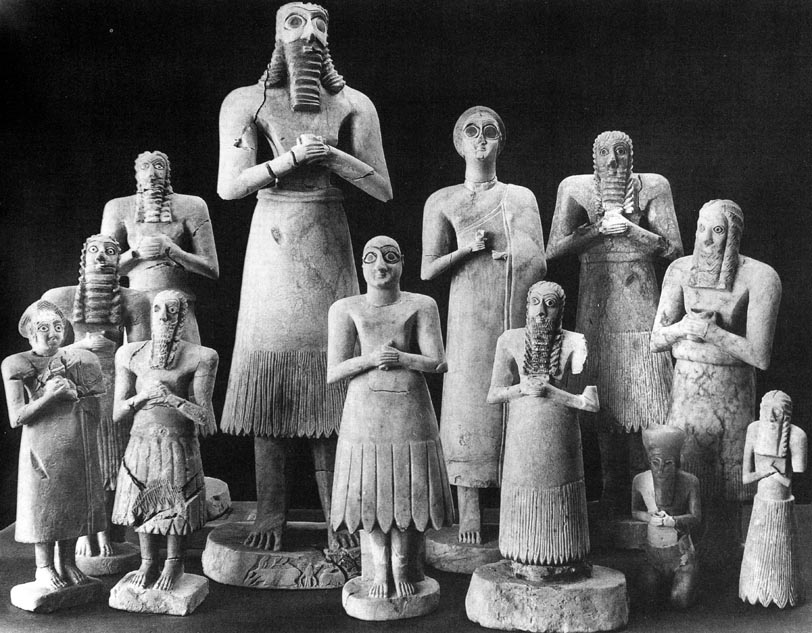

Twelve votive figures, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), c. 2900–2350 B.C.E. (Early Dynastic period)

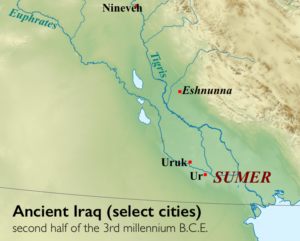

Twelve statues from the “Square Temple” at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq)

The group of twelve statues from Tell Asmar are among the most important examples of early sculpture from the Ancient Near East.

The figures date to the Early Dynastic period of ancient Mesopotamia (2900–2350 B.C.E.) and were discovered during excavations in Iraq in 1934. These figures were found below the floor of a temple known as the “Square Temple” (likely dedicated to the God Abu). They range in size (from 9 to 28 inches; 23 to 72 cm) and in condition (some still displaying painting and inlay; others broken). All of them, however, appear deeply focused, staring straightforward, some with very large eyes, most with hands clasped, some holding cups. The figures were excavated by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago but are now dispersed in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum, New York, the National Museum of Iraq, and the Oriental Institute, Chicago.

The figures and their archaeological context

Of the twelve statues found, ten are male and two are female; eight of the figures are made from gypsum, two from limestone, and one (the smallest) from alabaster; all would have been painted. They appear to all be performing the same act and what we know about their archaeological context can help us understand what that might be. One statue in particular stands out from the rest: the tallest man with long dark flowing locks.

Female and male votive figures (on the right is the tallest figure of the group of twelve), from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), c. 2900–2350 B.C.E. (Early Dynastic period) (The Iraq Museum, Baghdad; photo: Dr. Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Not gods, but adorants

From the Early Dynastic period sculptures such as these were common in temples. They are generally understood by art historians and archaeologists to be an image of the god to whom the temple was dedicated. They would be placed on raised platforms and were the recipients of gifts, as a proxy for the god.

However, the collection of statues from Tell Asmar appear to be of a different type, not images of gods and goddesses but rather adorants, mortals who stand in perpetual worship of the god of the temple. We know this because some of the statues are inscribed on the back or bottom with a personal name and prayer; others state “one who offers prayers.” Therefore, these sculptures represent a very early form of individual actions of faith, expressions of personal agency. Some of the sculptures are holding small cups which look a lot like a common cup of the era known as the solid-footed goblet. Hundreds of cups of this type were found deposited in a space near to the sanctuary where the sculptures were found, likely used to pour libations.

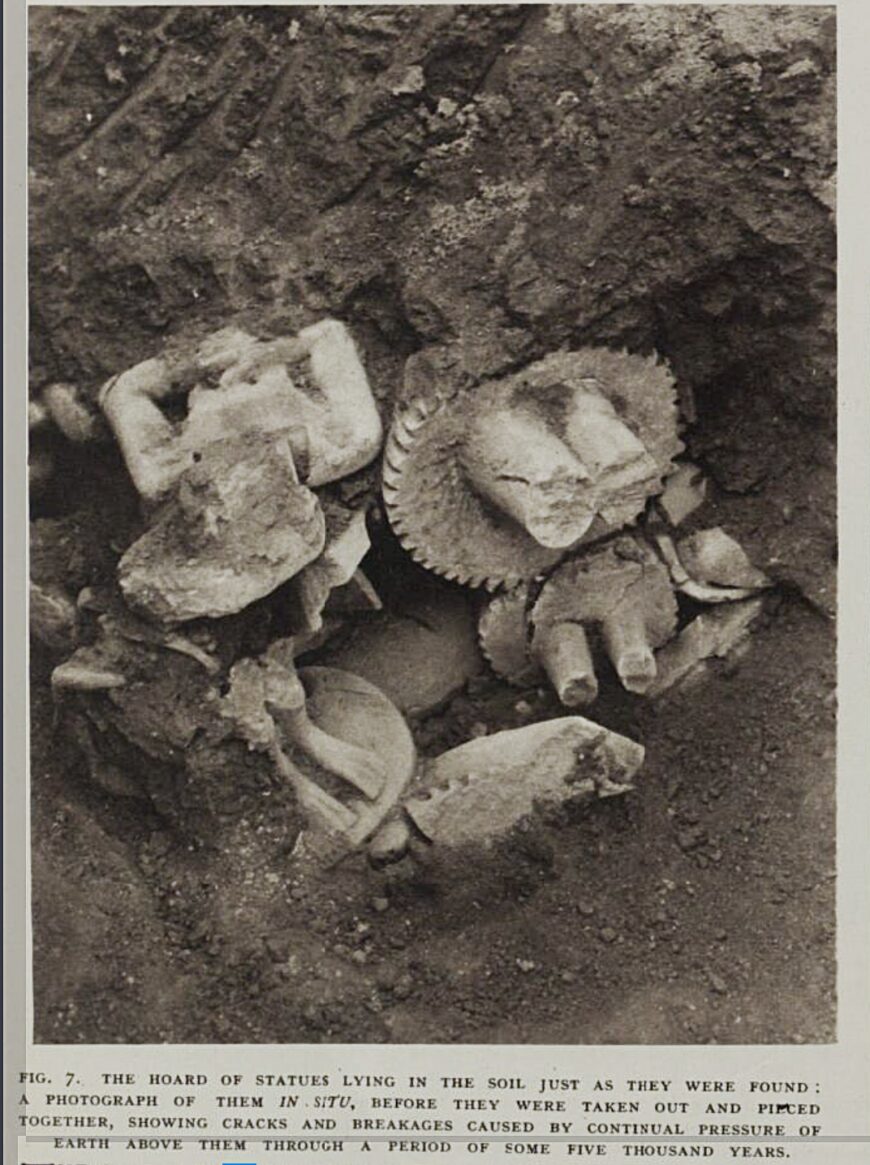

Caption: The Hoard of Statues Lying in the Soil Just as They Were Found, “An Extraordinary Discovery of Early Sumerian Sculpture,” Illustrated London News (May 19, 1934), p. 774.

Who were these early pious actors? The statues were discovered together, packed one on top of another in several layers within a 33 x 20 inch (85 x 50 cm) pit and just by the altar of the temple. Because of the circumstances of this find they are assumed to be a group of alike sculptures, although of a special kind, for sure. Given the high status material from which they are made, the inclusion of writing as well as their privileged space within the temple, we might assume these represent elite people, both men and women, interestingly.

Although their style is abstract and there is no sense of portraiture among them, they are all unique in small ways, either in the rendering of hair, facial expression or even feet; the material of the inlays is also variable, some of white shell or black limestone and even one of lapis lazuli. These sculptures might also represent a clue about how society was changing in the Early Dynastic period. Archaeologists believe that this group of sculptures representing mortals from Tell Asmar were not only working spiritually on behalf of each individual but also as a group, asserting a new status of elite non-religious classes within the context of the temple.

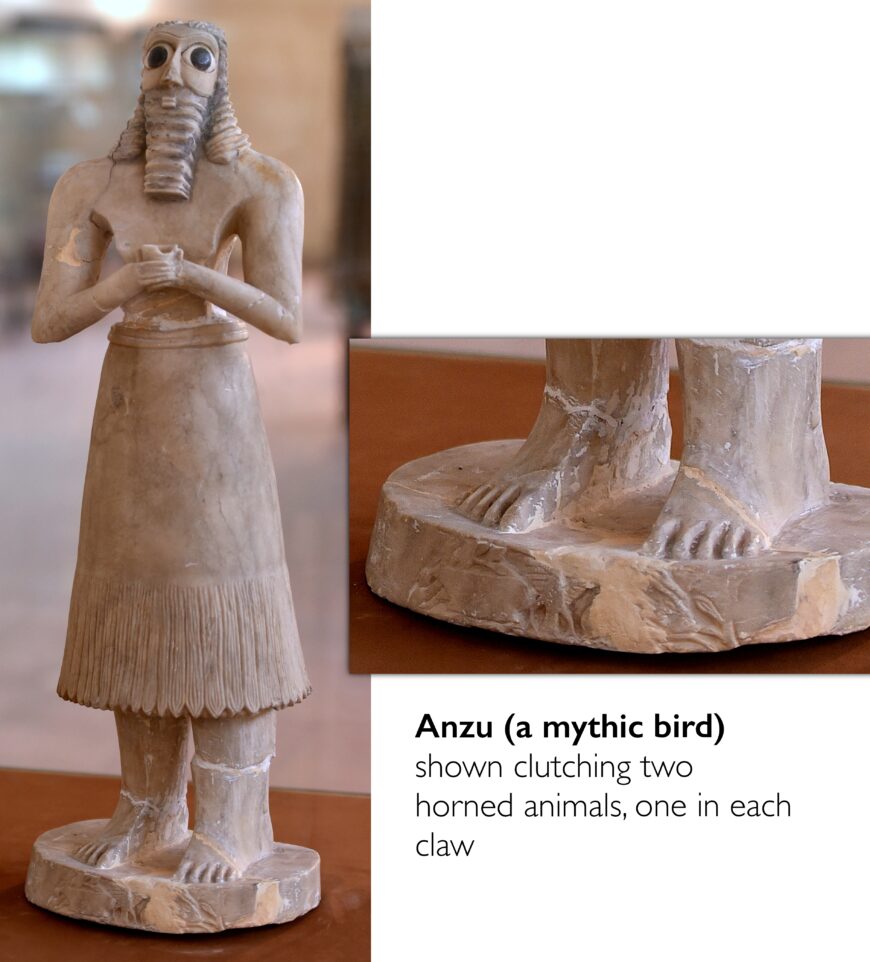

Feet and base (detail), Votive figure from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), c. 2900–2350 B.C.E. (Early Dynastic period) (The Iraq Museum, Baghdad; photo: Dr. Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CC BY-SA 4.0)

One figure who stands out

As mentioned above, one figure stands out from the group. He is the tallest with curly locks flowing down over his wide shoulders, his face slightly upturned, making him seem somewhat less obsequious than the rest. On the base of this sculpture there is a rough image carved as well, which also differentiates it from the others. This image shows an Anzu bird clutching two horned animals, one in each claw. This configuration—of Anzu clutching animals—is associated with the thunder god Ninurta (also known as Ningirsu), and also associated with the god of vegetation Abu.

Bird-god Anzu on the Votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, perforated relief, c. 2495–2465 B.C.E. (Ancient Girsu), alabaster, 15.1 x 21.6 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Votive figure from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), c. 2900–2350 B.C.E. (Early Dynastic period) (The Iraq Museum, Baghdad; photo: Dr. Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This figure’s luxurious hair, more engaging face and godly image on the base has led to his identification of a very old character type in Ancient Near Eastern art and literature, the long-haired hero who is sometimes nude and sometimes belted.

If this identification is true, we might wonder if the person who dedicated this statue saw himself as a heroic, Gilgamesh-like character (Gilgamesh was a hero in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem written during the late 2nd millennium B.C.E.).

Additional resources

Henri Frankfort, Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafājah (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”eshnunna,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] Almost 5,000 years ago, somebody carefully buried a small group of alabaster figures in the floor of a temple.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:13] We’re looking at one of those figures now. The Metropolitan Museum of Art calls this a “Standing Male Worshipper.” He was buried along with 11 other figures, for a total of 12, most of them male.

Dr. Zucker: [0:25] We’re looking at one of the smaller figures. They range from just under a foot to almost 3 feet.

Dr. Harris: [0:30] The temple where these were buried was in a city called Eshnunna in the northern part of ancient Mesopotamia.

Dr. Zucker: [0:37] What is now called Tell Asmar. The figures from Tell Asmar are widely considered to be the great expression of Early Dynastic Sumerian art. We think that the temple was dedicated to the god Abu.

Dr. Harris: [0:49] At this time, the 3rd millennium B.C.E., [in] this area around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, some of the earliest cities in the world emerged and writing emerged. This is a watershed in human history. The cities had administrative buildings, temples, palaces, many of which have been unearthed by archaeologists.

Dr. Zucker: [1:09] This is the transitional period right after the Bronze Age, at the tail end of the Neolithic, when civilizations are founded in the great river valleys around the world. He’s adorable.

Dr. Harris: [1:20] He is adorable. His wide eyes and his sense of attentiveness are very appealing, I think. Of course, he wasn’t meant to be looking at us. He was meant to be attentive to a statue, a sculpture of a god who was believed to be embodied in the sculpture.

Dr. Zucker: [1:37] In fact, we believe that the person for whom this was a kind of stand-in was also embodied in this figurine.

Dr. Harris: [1:44] An elite member of ancient Sumerian culture paid to have this sculpture made and placed before the god to be a kind of stand-in, to perhaps continually offer prayers, to be continually attentive to the god.

Dr. Zucker: [1:59] His hands are clasped together. He stands erect. His shoulders are broad, so there’s a sense of frontality.

Dr. Harris: [2:06] Even though he’s carved on both sides, he was meant to be seen from the front, although that term “meant to be seen” is a funny one.

Dr. Zucker: [2:12] He was meant to be seen by a god. You can see that the hair is parted at the center of the scalp and comes down in wavelets or perhaps braids that spiral down and then frame the central beard, which is quite formal, and cascades down in a series of regular waves.

[2:27] His hands are clasped just below the beard. His shoulders are really broad, his upper arms very broad, and then there’s very fine incising at the bottom of his skirt.

Dr. Harris: [2:38] It’s odd to me how cylindrical the bottom part of his body is and how flattened out the torso is.

Dr. Zucker: [2:45] If you look at the face carefully, you can see that the very large eyes are in fact inlaid shell. In the center, the pupils are black limestone, and you can also see that there’s incising of the eyebrows that might have originally been inlaid as well.

Dr. Harris: [2:58] This is really different from Egyptian culture, which emerges at the same time. In Egyptian culture, the sculptures primarily represent the pharaoh, the king, and indicate his divinity. In the ancient Near East, instead, we have these votive images of worshippers but not so much of the kings. At least during this Early Dynastic period.

[3:19] The figures at Tell Asmar that were unearthed are very similar. They’re not meant to be portraits of a specific person, but a symbol of that person.

Dr. Zucker: [3:29] He does look very humble. His mouth is closed, his lips are sealed together, and of course he is wonderfully attentive.

Dr. Harris: [3:36] The fact that his hands are clasped, I think, makes him seem more humble as well.

Dr. Zucker: [3:41] There are some interesting, subtle choices that whoever carved this made. Look at the way that the skirt extends out and attaches itself to the forearms, a bit wider than we would expect.

Dr. Harris: [3:53] The torso, it’s just this almost V shape. There is a sense of geometric patterning here and not the naturalistic forms of the body.

Dr. Zucker: [4:02] If you look at the back of the figure, you can see that there’s a little cleft that’s been carved in horizontally, and there’s also what seems to be the indication perhaps of a tied belt that hangs down.

Dr. Harris: [4:13] You understand, I think, the artist’s decision not to make a naturalistic figure because a naturalistic figure before the god might give a sense of someone just visiting, just passing through. This idea of a static, symmetrical, frontal, wide-eyed figure gives a sense of timelessness, of a figure that is forever offering prayers to the god.

[4:36] [music]