Wine Bearers in Landscape (textile fragment depicting a figure in a landscape) (attributed to Iran), 16th century, silk (lampas), 101.6 x 36.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Young men carry cups and long-necked bottles of wine in a lush garden. Fish splash in ponds, animals roam freely and can be found under bushes and behind boulders, birds alight on tree branches or flit through the air; and a breeze spreads the scent of flowers in the air and tenderly bends the cypresses. It may not be easy to distinguish the youths from the surrounding natural environment at first glance as they are embedded in a dense scene on a textile fragment known as Wine Bearers in Landscape.

This luxurious and exquisite silk fabric was woven in Iran during the sixteenth century reign of the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp I. This was a period of robust sericulture and silk weaving in the region, when the Safavids were among the major silk exporters in a global market.

Fabrics of wealth and power

Wine Bearers belongs to a group of luxurious early modern fabrics. Silk was expensive worldwide and in high demand among the elites in the sixteenth century. These fabrics were created using a highly sophisticated weaving technique called lampas, which was among the most advanced technologies of the early sixteenth century. This particular textile is constructed with approximately 100 warps (vertical threads) and 30 wefts (horizontal threads) in each centimeter, equal to 250 warps and 75 wefts in each inch, an extremely high thread count. The higher the thread count, the softer the fabric and the more intricate the pattern. By comparison, thread counts could be two to ten times less dense in a simpler, coarser fabric.

The result is an extravagant, labor intensive textile that added substantial value to the already expensive silk from which it was made. These luxurious fine fabrics were made for the wealthy social and political elites.

Lion (detail), Textile fragment depicting a figure in a landscape (attributed to Iran), 16th century, silk (lampas), 101.6 x 36.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo: Nader Sayadi)

Fabrics such as Wine Bearers were commonly cut and sewn into garments for nobles and other wealthy patrons and this may account for the unusual shape of this cloth. They were worn not only because they were beautiful to the eye and soft to the touch, but also because they functioned as symbols of high social, economic, and political status. Although these textiles were once frequently worn by the highest strata of Safavid society, few have survived. In a contemporaneous painting by Muhammad Haravi, a young noble is depicted wearing a garment made from similar fabrics. Wine Bearers is among a very few well-preserved examples of these silks to have survived the five hundred years since they were woven. Today, these objects adorn museum galleries and private collections, but for their original owners, they had very different functions and meanings.

Young Prince with a wine cup and a long-necked bottle, wearing a silk robe adorned with figural motifs (detail); Muhammad Haravi, Young Prince (detail), mid-16th century (Safavid, Iran), opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 34.1 x 24 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Wearable poetry of love, wine, and youth

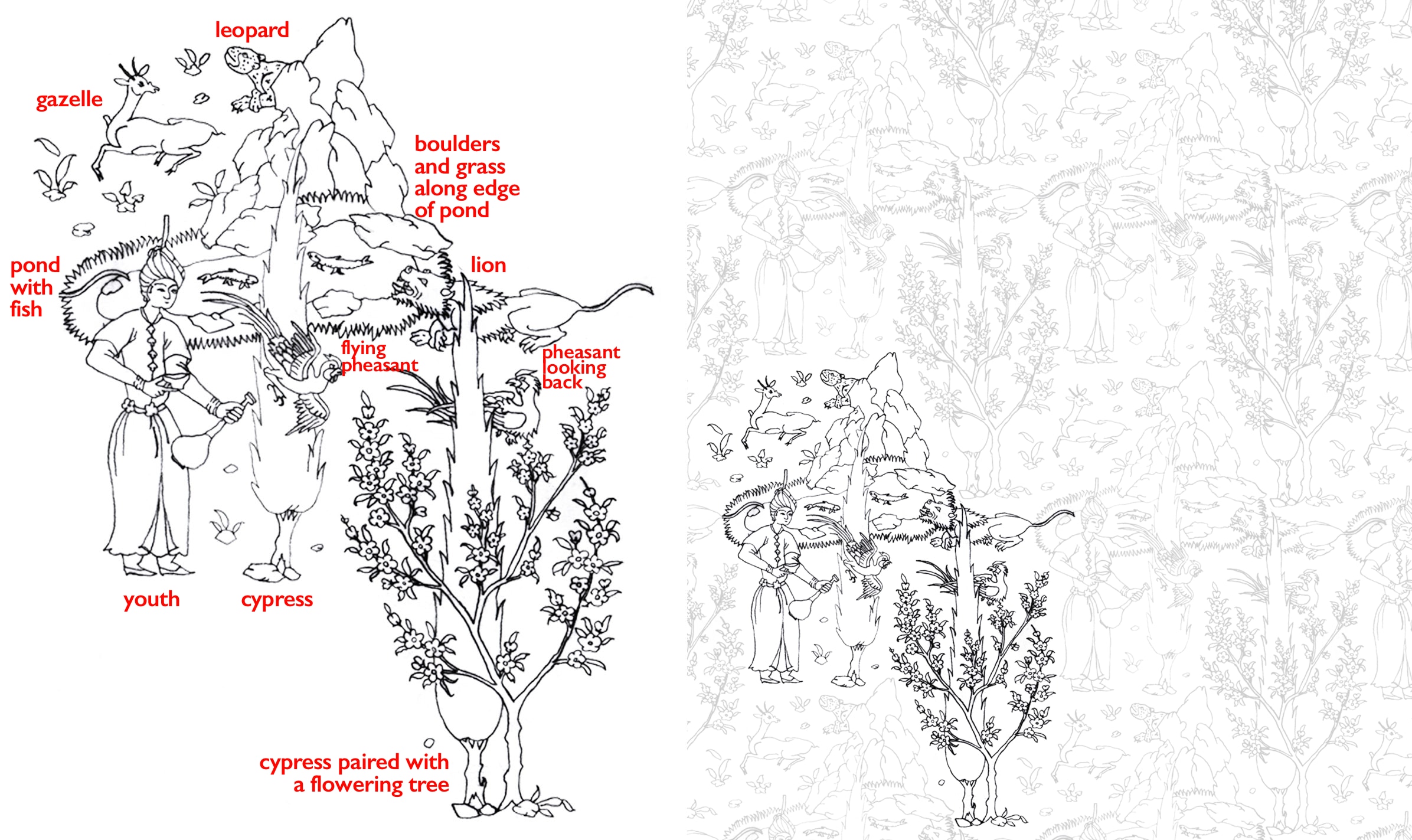

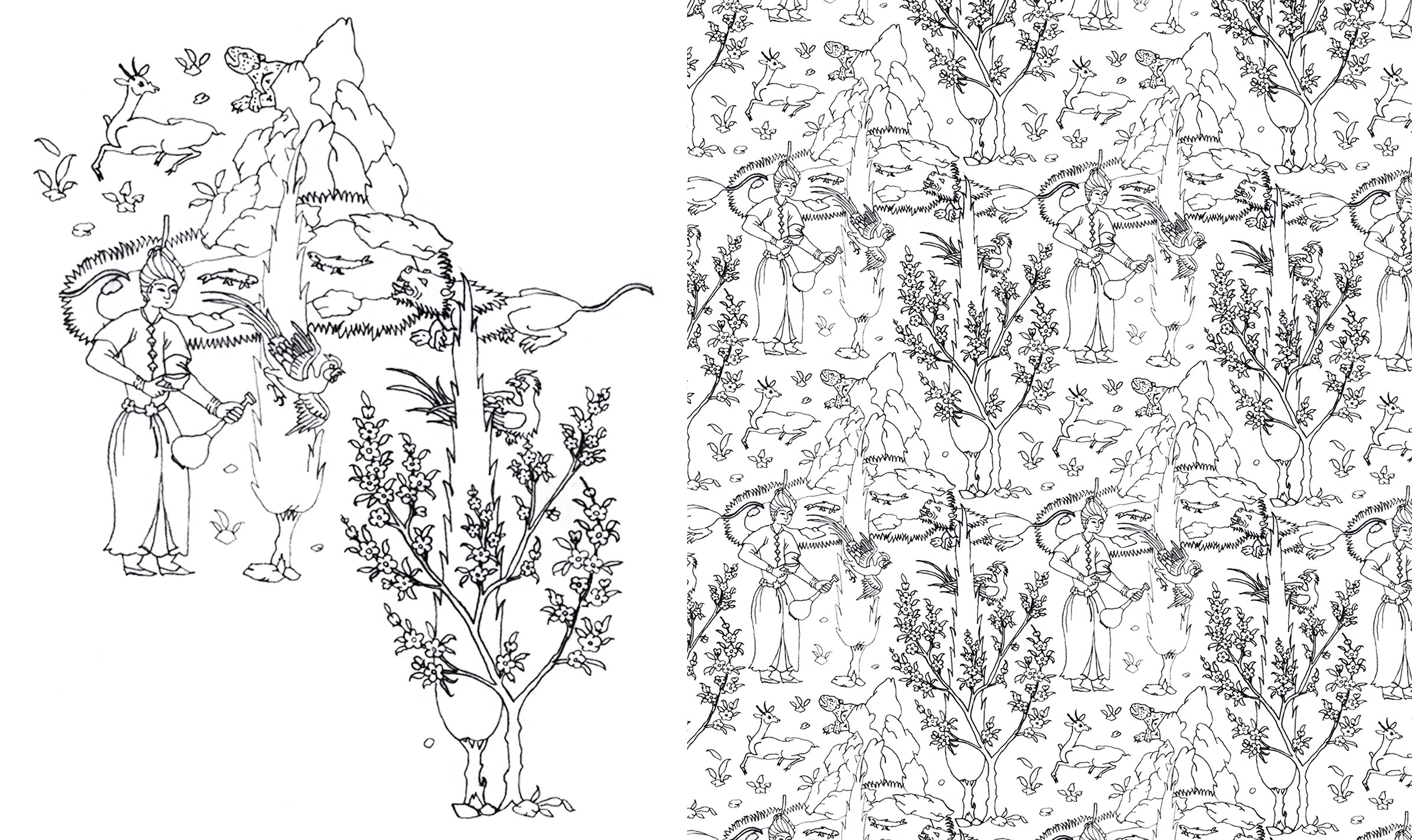

Textile fragments such as Wine Bearers can illuminate a time when textiles were not only at the cutting edge of trade and technology worldwide and a representation of their patrons’ wealth and social status, but also woven poetics of love, wine, and youth. Looking closely, one may notice that a specific set of elements recur: one youth; one pond with fish, boulders, and grass along the edge; one cypress, and then another cypress, this one paired with a flowering tree; one sitting pheasant looking backward; another flying in front of the single cypress; a lion on the pond’s far right; a leopard behind boulders; and a gazelle in front of the leopard. These elements form a visual unit, which is repeated to create a continuous pattern across the fabric. Safavid designers perfected this millennia-old compositional technique, creating complex repeating units. Despite the narrow cut of this textile fragment, these intricate jigsaw-like patterns suggest that these patterns might extend in all directions endlessly, representing eternal continuity, and resulting in a kaleidoscopic feast for the eye and for the mind.

Repeat from Textile Fragment Depicting a Figure in a Landscape (drawing: © Nader Sayadi and Mohamad Karimifar, all rights reserved)

Ibn Sukkara al-Hashimi, Cup (pīyāli) with a Poem on Wine, second half 10th–11th century (attributed to Iran), silver, 8.3 x 17.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Wine Bearers does not represent an actual event or place. Nor are the youths specific people. Instead, this landscape illustrates an imagined scene within an abstract space to portray an ideal state of being—one that celebrates being young, intoxicated, and in love.

Surāhī, late 16th century (Mughal India), brass, 22.5 x 11 cm (© Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

This ideal state of being is represented through a series of iconographic and semantic elements. The fabric portrays the themes of intoxication and youth. The cup (pīyāli) and the long-necked bottle (surāhī) depicted in Wine Bearers are vessels that were commonly used for drinking wine in Safavid Iran. These visual references allude directly to intoxication. The human figures refer to the theme of youth. The wine bearers wear the typical attire of a Safavid nobleman in the second quarter of the sixteenth century, specifically a turban wrapped around a cap with a tall, baton-like finial called tāj. It shows a three-quarter view of the face and body. The human figure is depicted with a slender body, short hair, and lack of facial hair. These stylistic elements in aggregate suggest an idealized image of youth, which was a common trope in Safavid art.

Love in Persian poetry

Unlike the wine and youths, the representation of love might be less clear to a modern viewer since the textile does not offer overt visual clues to the theme of love. For example, the repeat unit shows a a young man alone, instead of a couple. To reveal the presence of love, one must look beyond the visual elements of the textile and focus instead on its cultural and historical context. Themes of love, youth, and wine were often represented together in Iran’s visual and literary traditions for at least the past millennium. In this sense, the appearance of two of these elements suggests the presence of the third. These themes were particularly popular in Persianate poetic traditions. Among others, the divan of Hafiz of Shiraz epitomizes this genre:

Love (-making) and youth and ruby-colored wine;

peaceful gathering and cup-sharing companion and continual [wine] drinking;

Sugar-mouthed wine server (cupbearer) and a sweet-voiced minster;

a seated companion of good deeds and companion of good name;

A beloved the envy of the water of life in terms of graciousness and purity;

a beloved in beauty and goodness the envy of the full moon;

A pleasant banquet place like the castle of lofty paradise;

a garden around it like the garden of the house of salam (i.e. the paradise)Divan by Hafiz[1]

As illustrated in this poem, the conception of love in Persian literary tradition could be literally or figuratively interpreted in a spectrum from earthly to metaphorical love. One end of the spectrum referred to the love for human beauty, while the other alluded to a mode of being with God or Divine Truth in contemporary mystic and Sufi practices. In either case, wine is a crucial instrument to deepen, expand, and facilitate the experience of love. The interplay of love and wine embodies a perfect state of being by referencing the concept of the everlasting in the form of eternal youth.

lion, pheasant, and paired trees (detail), Textile Fragment Depicting a Figure in a Landscape (attributed to Iran), 16th century, silk (lampas), 101.6 x 36.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Representing paradise

Other visual elements depicted in Wine Bearers, such as flora and fauna also reinforce this perfect state of being. The stylized trees, blossoms, and shrubs represent an idealized garden (bāgh), the Garden of Eden, or Paradise (which is pairidaeza in Avestan, and pardīs in modern Persian) as a place of eternal peace, calm, and joy.

The trees particularly call attention to two opposed but interlocking concepts: the eternal and the ephemeral. Two types of trees are depicted: a deciduous tree in bloom—possibly a cherry, apple, or peach—and evergreen cypress. Unlike the evergreen cypress, deciduous trees lose their leaves in the fall and blossom in the spring. In this sense, cypresses represent a mode of being not affected by time, while the deciduous tree represents the passage of time. Their juxtaposition symbolizes a universe balanced between the transient and the eternal.

The fauna depicted in this scene refer to the universe’s primary elements (or classical system of elements) in several cultures, including the Iranian cultural tradition. These elements are earth, air, water, and fire. The universe’s living entities exist in environments made from the first three elements. In the scene, the mammals (the gazelle, the lion, and the leopard), the birds (the pheasants), and the fish represent respectively the creatures of the earth, the air, and water. Collectively, they epitomize the classical system of elements and the universe more broadly.

We can gleam another meaning by looking at how the mammals interact. The lion and the leopard are in similar positions: they both lie on their bellies with their front paws crossed. The leopard seems to gaze at the young man. The gazelle, in turn, also appears relaxed, as it looks backward to the leopard nearby. This scene pictures an imagined space where prey and predator exist in a harmonious and conflict-free environment. All of the fauna illustrate an idealized microcosm where all the universe’s elements are in balance and peace.

Fritware bowl, c. 1200 (Kashan, Iran), ceramic with polychrome decoration and gold leaf in and over an opaque, white glaze (Minai type), 8.5 x 21.7 cm (The David Collection, Copenhagen)

Beyond textiles

Wine Bearers’ visual elements belonged to a larger visual tradition in Islamic art that depicts love, wine, and youth. These elements can be found on numerous objects in a variety of media including paintings, ceramics, and textiles. For example, a ceramic bowl from the thirteenth century features youths, a wine cup and bottle, a deciduous tree in bloom, cypress, birds, fish, and pond—though rendered in a different style.

Painting with detail of man holding a cup and a long-necked bottle, c. 1520 (Safavid, Iran) from Divan-i Khata’i (Collected poems) by Shah Isma’il I, ink, opaque water color, gold on paper, 21.8 x 14 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Contemporary arts of the book reveal several parallels to Wine Bearers in both theme and artistic style. An illustration from a copy of the Khata’i Divan, a book of poetry by Shah Isma’il I, demonstrates similar visual elements: on the lower right, a youth, maybe a young man, carries a cup and a long-necked bottle of wine in a landscape or garden which includes a pond, birds, and a cypress and flowering deciduous tree. A primary difference is that the young man has company. This painting visualizes its accompanied poem:

I have never seen anyone so beautiful as you on the earth,

never in this world anyone as gorgeous as you.

Truly within the garden of the soul there can be

no gesture so elegant as your tall erect cypress.

Although there are many beauties among humanity,

there is none, O Beauty, so radiant as you.Divan-i Khata’i by Shah Isma’il I [2]

The themes of youth, love, and wine continued inspiring the arts of Iran and the Islamic world, particularly in the material culture depicting love stories such as Khusraw and Shirin by Nizami.

First adorning the body, then the museum

Little is known about the meaning and function of these sixteenth-century fabrics during the intervening centuries. As tastes changed in society, so too did the way these fabrics were seen and used. Fabrics such as Wine Bearers were already out of fashion as items of attire in mid-eighteenth-century Iran. Several paintings show Iranian elites wore printed cottons, monochrome silks, and cashmere shawls in the second half of the eighteenth century. Silk fabrics depicting Safavid youths drinking wine or similar patterns only survived perhaps in private and royal treasuries until they came to light again in the art markets of the mid-nineteenth century. They were either recycled and resewn into other items, or dismantled by art dealers in the nineteenth or early twentieth century to be sold to both public and private collections. As a common practice, art dealers removed the stitches that held together a garment or cut up a textile to sell to multiple collectors. As a result, few Safavid garments remain intact.

Gazelle and leopard (detail), Wine bearers in landscape, from a robe, 1525–50, silk (lampas), 85.1 x 38.1 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

Wine bearers—now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art—was once part of a garment that is now lost to us. Several matched fragments in museums around the world are perhaps the only traces of this lost garment. These textile fragments can be found in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Once adorning the wealthy as personal attire, these fabrics became subject to a voracious art world and were transformed from clothing hung in a wardrobe, to artifacts framed and mounted on museum walls as if they were oil paintings.

Beautiful Safavid fabrics like Wine Bearers grace collections of Islamic art and textiles worldwide. Today, we admire them as reflections of highly sophisticated textile technology, elaborate design, and prosperous silk economies in the early modern world. Safavid nobles most likely saw these wearable poems differently: by wearing garments made from such precious fabrics, their owners showed off their wealth and high social status, while they wrapped themselves in poetries of love, wine, and youth.