View of the site from north, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Otto Nieminen/Manar al-Athar)

The Umayyad prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (later the caliph “al-Walid II”) was known during and after his life as a hedonist. His most famous architectural commission, Quṣayr ʿAmra—with its frescoes of nude women and animals playing music—seems to corroborate this reputation. But a closer look at the structure’s site and decorative program reveals how an Umayyad prince imagined the world and his place in it.

Quṣayr ʿAmra (“the little palace of ʿAmra”) was commissioned and built by the prince al-Walid when he was still heir apparent, probably in the early 730s C.E. [1] We know this with some certainty because of an inscription (on the south wall of the reception hall) that includes his name without a caliphal title. The partially surviving inscription reads: “O God, imbue al-Walid ibn Yazid with righteousness…” [2]

![Arabic inscription with partial transcription overlay [see Footnote #2], fresco on the south wall of the west bay of the reception hall (detail), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik, (overlay: Courtney Lesoon CC BY; photo: Otto Nieminen/Manar al-Athar)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/image-4-base.jpg)

![Arabic inscription with partial transcription overlay [see Footnote #2], fresco on the south wall of the west bay of the reception hall (detail), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik, (overlay: Courtney Lesoon CC BY; photo: Otto Nieminen/Manar al-Athar)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/image-4-overlay-1.jpg)

Arabic inscription with partial transcription overlay [see Footnote #2], fresco on the south wall of the west bay of the reception hall (detail), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik, (overlay: Courtney Lesoon, CC BY; photo: Otto Nieminen/Manar al-Athar)

Al-Walid was only fifteen-years old when his father, the caliph al-Yazid II, died. Because of this, the caliph’s brother was named as his successor with the understanding that upon his death the title would then be passed down to al-Walid. This unusual arrangement meant that from the age of fifteen until he became caliph at the age of thirty-four, al-Walid was preparing and working carefully to secure his place as leader of the Islamic world.

Portrait of the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik with his two sons (detail), fresco on the south wall of the west bay of the reception hall, Quṣayr ʿAmra (photo: Agnieszka Szymanska/Manar al-Athar)

Quṣayr ʿAmra is a great example of how art and architecture (i.e., “material evidence”) can reveal histories that are otherwise inaccessible through textual sources. Most surviving texts that describe the prince al-Walid were written under the patronage of the Abbasids, who ultimately overthrew the Umayyads in 750. These textual sources are unsurprisingly biased against the prince and against the Umayyads. But fortunately, Quṣayr ʿAmra survives. Its architecture and decorative program reveal first hand how its patron fashioned himself as a ruler and extended his social and political power across the region.

Site and context

Quṣayr ʿAmra is located about 130 km east of Jerusalem and 190 km south of Damascus in a place called Wādī al-Buṭum, a mostly arid plain that experiences irregular bouts of rainfall, often followed by flooding.

Quṣayr ʿAmra is just one of several extant Umayyad structures that scholars have collectively and loosely referred to as “desert palaces.” These were located far away from cities and were not usually intended for year-round use. “Desert palaces” functioned as seasonal accommodations for traveling courts, who for the most part slept in elaborate tents nearby.

In the time of al-Walid, the area of Wādī al-Buṭum was a prime location for hunting because the flood waters and resulting foliage attracted prey animals such as gazelles. The prince al-Walid hosted and entertained his guests for hunts and feasts at Quṣayr ʿAmra. This helped him build political alliances that benefitted his position in the Umayyad court. And Quṣayr ʿAmra’s distance from the capital city of Damascus allowed him to cultivate these alliances away from prying eyes.

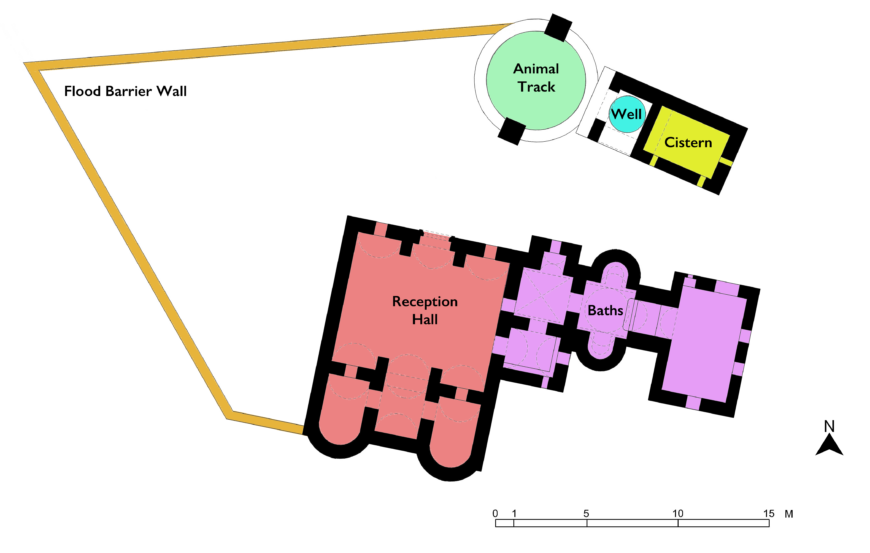

Site plan with labels “Reception Hall,” “Baths,” “Flood Barrier Wall,” “Animal Track,” “Well,” and “Cistern,” Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (image: Courtney Lesoon, CC BY, after Nasser Rabbat / Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, MIT)

Walking through the architecture

The main structure of Quṣayr ʿAmra is comprised of a reception hall and a luxurious bathhouse. Around the western side of the complex is a flood barrier wall. [3] On the northern side is a small circular animal track, on which a camel could, by walking in a circle, activate a mechanical water wheel called a saqīya. This would draw water from the enclosed well beside it and dispense that water into the adjacent rectangular cistern for storage.

View of reception hall from entrance with inset of detailed plan of reception hall with labels “Entrance,” “East Bay,” “Center Bay,” “West Bay,” “East Chamber,” “Throne Alcove,” and “West Chamber,” Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (image: © TrueMarkets 3D/ Google; plan: Courtney Lesoon, CC BY, after Nasser Rabbat / Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, MIT)

Reception hall

Entering Quṣayr ʿAmra, guests of al-Walid would have found themselves in an intimate but imposing reception hall, perfectly designed for its function. The hall is made up of three barrel-vaulted bays supported by two wide arches, which create a single interior space that the prince and his guests could share. The walls and ceilings are covered in elaborate frescoes that invite visitors to look closely. These exciting illustrations (which are discussed below) were most certainly sources of entertainment for al-Walid’s guests. Windows along the north, south, and east walls of the reception hall let in fresh air and sunlight. The lack of windows on the west wall prevent afternoon sun from overheating the interior, keeping it cool even in summer.

Throne alcove (left) and detail of illustration of enthroned prince (right), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (left photo: Christian Sahner/Manar al-Athar; right photo: Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar)

In the central bay, directly across from the entrance is an alcove in which the prince al-Walid would have sat enthroned to receive his guests. On the wall above and behind where the prince al-Walid would have sat enthroned, is an illustration of exactly this: an enthroned prince receiving guests! To the right and left of this throne alcove are entrances to two flanking chambers that extend beyond the reception hall.

Exterior of the throne alcove and two flanking chambers with labels “west bay,” “center bay,” “east bay,” “west chamber,” “throne alcove,” and “east chamber,” view from the southwest, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 723–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Marlena Whiting/Manar al-Athar)

Structurally, these two chambers are also barrel vaults, but much lower in height than those of the reception hall. Each of these rooms conclude in a semi-domed apse. Only some frescoes in these rooms have survived. But the well-preserved mosaic floors in these chambers hint at what would have originally covered the floors of the main reception hall and the baths.

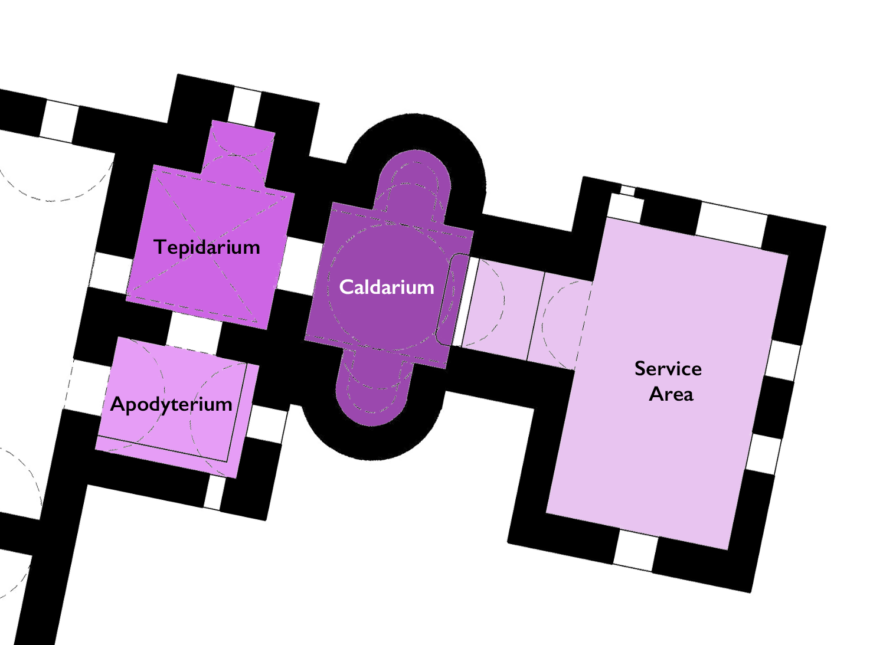

Detailed plan of baths with labels “Apodyterium,” “Tepidarium,” “Caldarium,” and “Service Area,” Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (image: Courtney Lesoon, CC BY, after Nasser Rabbat / Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, MIT)

Baths

The baths of Quṣayr ʿAmra are entered from a door on the east wall of the reception hall. The rooms of the bathhouse begin first with a barrel vaulted apodyterium (changing room), then to a groin vaulted tepidarium (warm bath), and culminate in a domed caldarium (hot bath). The large space to the east of this, visible on the plan below but inaccessible from the bath itself, is a service area. Here servants would have stored fuel to feed the fires below the floors of the two baths and manage the hydraulic system that fed water from the nearby cistern into the baths.

While private bathhouses were ostentatious displays of wealth anywhere, they were especially so in such a remote location. Guests at Quṣayr ʿAmra were no doubt impressed by such a luxury. And al-Walid offered this impressive amenity to his guests in exchange for political allegiances and good will.

To get a sense of the space, explore this virtual tour of Quṣayr ʿAmra:

3D Tour (c. October 2023) of Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (© True Markets 3D / Google)

Gazing at its frescoes

Qusayr ʿAmra’s frescoes undoubtedly represent the worldview of the prince al-Walid. But they also reveal what iconography and illustrative styles were fashionable in the Umayyad court.

Much of the imagery inside Quṣayr ʿAmra is figural (i.e., depicting the human form). Although there were some prohibitions against figural imagery in this period, these regulations only applied to the decoration of mosques. Private homes and palaces were frequently decorated with figural imagery and even sculpture (for example this female figure excavated at another “desert palace”).

Fresco on vault of central bay, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 723–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Daniel C. Waugh Archive, Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT)

Nearly every surface of the reception hall is painted, even the ceilings. [4] The vault of the center bay contains a grid of figural vignettes separated by dark blue bands of white and red floriated roundels. Each vignette features one or more figures framed by the same architecture: a pair of columns topped with a gabled roof. Such features recall Greek and Roman temples, many examples of which were nearby and well known to the Umayyads. Classical design (i.e., ancient Greek and Roman and architecture) greatly influenced Umayyad architecture. The Great Mosque of Damascus, for instance, even employed Roman spolia in its construction.

Vault of the east bay of the reception hall, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 723–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Daniel C. Waugh Archive, Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT)

On the barrel vault (a Roman architectural form!) of the east aisle are rectangular vignettes of figures performing various occupations, such as carpentry and smithing. These vignettes are divided by simple white margins that give the illusion of coffers on the ceiling.

Why would the prince al-Walid want to feature so many working class figures in this very royal and upper-class reception hall? These figures, doing their daily work, represent the different “crafts” of a society that together contribute to a civilization. And al-Walid was invested in presenting himself at the helm of this civilization.

Fresco on the west wall of the reception hall, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: MCID Columbia University)

The vault of the west bay is covered partially with a hunting scene that seems to extend from the horizontal registers on the wall below. Hunting was something that al-Walid II and his entourage knew well. This and other hunting frescoes in the reception hall are filled with local details, for example onagers, oryxes, and saluki dogs. These illustrations were intended to excite and engage viewers who might find themselves lucky enough to go on a hunt with the prince.

“Bathing beauty,” fresco on west wall of reception hall, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: MCID Columbia University)

On the register below this hunting scene is perhaps Quṣayr ʿAmra’s most striking illustration. She is the “bathing beauty” who looks confidently out at the viewer. The artist has depicted her in a blue pool of water on what seems to be a base of columns. But this is not a rooftop bath. Rather, the artist means to convey with this composition that the bath is surrounded by columns (like this one). The whole scene takes place inside a bathhouse, indicated by the framing architecture behind the bathing beauty. A group of onlookers peek from behind a screen. They stand in what is the bath’s surrounding building, which features an impressive arcade supported by Corinthian columns.

“Bathing beauty,” fresco on west wall of reception hall (detail), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: MCID Columbia University)

Although it is possible for art historians to describe the different elements of this image (and even trace their iconographic origins), the meaning and impact of this illustration on its original audience is now lost on us as modern viewers.

“Fresco of the Six Kings,” fresco on west wall of reception hall (detail), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 723–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar)

On the same register, directly to the left of the enigmatic bathing beauty, is an illustration referred to as “the fresco of the six kings.” Now badly damaged, it depicts and labels (in Greek and Arabic) six kings of recent history.

Four of these inscriptions are legible. They are “Caesar” (the king of the Roman world), “Roderic” (the king of the Visigoths who had been recently defeated by the Umayyads in 711), “Kisra” (a.k.a. Khosrow II, the king of the Sasanians who died in 628), and “Najashi” (the king of the Aksumites who died in 630).

Each king gestures with both hands to his right, presumably to the portrait of the prince al-Walid depicted on the adjacent wall. Because of the location of this fresco, these six kings also seem to be gesturing in the direction of the throne alcove, where al-Walid would have actually sat.

Portrait of the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik, fresco on the south wall of the west bay of the reception hall, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Agnieszka Szymanska/Manar al-Athar)

It is striking that al-Walid II doesn’t illustrate himself as a conqueror of these kingdoms, but as a magnet of these six king’s esteemed attention and respect. This illustration of the six kings serves to bolster the image of the prince al-Walid not as a strongman (which he could hardly claim) but as a future and legitimate leader of another great civilization.

Astronomical chart, fresco on the underside of the dome of the caldarium, Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 723–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: Steve Welsh/Manar al-Athar)

Painted on the dome of the caldarium is an elaborate astronomical chart with allegorical figures representing different constellations. Still visible are an archer centaur (Sagittarius), a big and little bear (Ursa Major and Minor), and a man wrestling a serpent (Ophiuchus).

You can imagine looking up into the dome, wishing that you could see the starry sky above, only to realize that it has been illustrated for you! This is thought to be the earliest known astronomical illustration rendered on a curved surface.

The afterlife of Qusayr ʿAmra

Qusayr ʿAmra was not used for very long, probably because of unpredictable water supply, but also because of al-Walid’s short reign as caliph (he was assassinated in 744 C.E., only fourteen months after ascending the throne).

Because of its remote location, far east of the pilgrim road from Damascus to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, Qusayr ʿAmra was more or less unknown to the broader Islamic world for centuries. In the 19th century, the Bedouin who did know of Quṣayr ʿAmra apparently deemed it haunted and so for the most part avoided the place. This convergence of circumstances led to a remarkably well-preserved structure that the Czech scholar Alois Musil came upon unexpectedly in 1898.

When Alois Musil saw the site, he assumed that it was a Late Roman cult structure. At the time, it was unthinkable that a Muslim patron would have commissioned so many figural images, let alone nude women. Musil’s apparent discovery was huge news in the European academy because no one knew of any Roman frescoes made after the eruption of Vesuvius 79 C.E. (those of Pompeii and Herculaneum). It was such an incredible “discovery” that Musil’s funders back in Europe thought that he was scamming them!

The famed father of art history, Alois Riegl (a different Alois), spent the last years of his life consumed by the question of Quṣayr ʿAmra. Was it Roman? Was it Islamic? Despite the overwhelming evidence that it was Islamic (including Arabic inscriptions!), Riegl maintained until his death that Quṣayr ʿAmra was a Roman structure.

Restoration in progress, uncleaned and cleaned portions divided by segmented white line, fresco on the south wall of the west bay of the reception hall (detail), Quṣayr ʿAmra, Jordan, 724–744 C.E. (Umayyad), stone masonry, interior decorated with wall frescoes and mosaic floors, patron: the prince al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (photo: A Reyes/E Khamis/Manar al-Athar)

In part because of Quṣayr ʿAmra, art historians now understand early Islamic art to be a culmination (and not an imitation) of the many design traditions that Islam encountered in its first centuries, including that of classical antiquity. Uniquely, Quṣayr ʿAmra seems to suggest that its patron actually imagined the Islamic world in these terms (as a culmination of the great civilizations of the past!). And with the rich visual language of the region to convey his ideas to his audience, the prince al-Walid inserted himself into this history, presenting himself at the center of this new world.