How to do an iconographic analysis

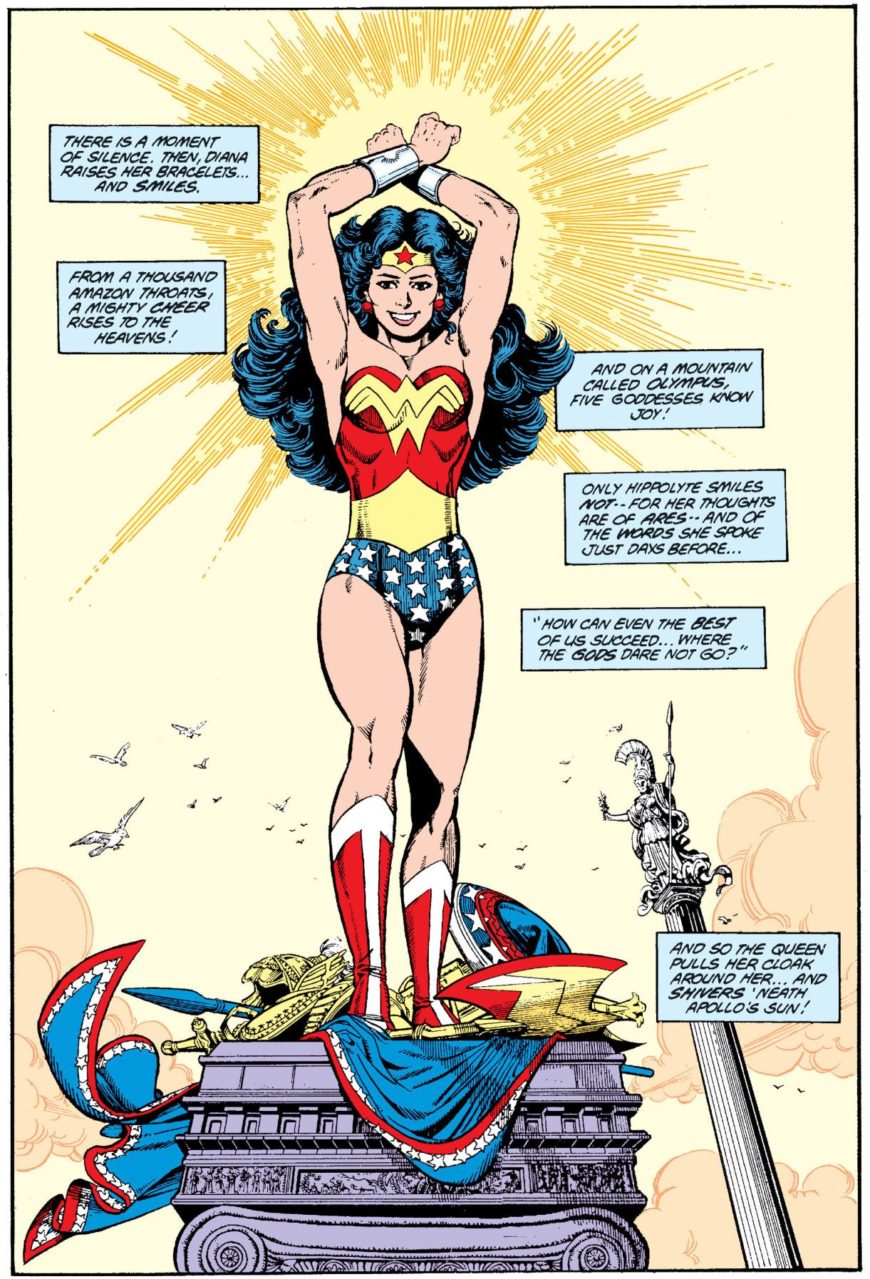

Take a look at this image. Who is this? What symbols do you notice that help to identify the subject? You’ll notice that this is a drawing of a human figure dressed in a tight-fitting bodice of red and yellow; blue briefs with white stars; and tall, red boots. A golden design stretches across their chest, appearing like the letters WW stacked atop one another in the form of a bird. The figure also wears headgear decorated with a red star, and silver wristlets. Long blue-black hair cascades down their back, and they have a well-developed musculature. To identify the subject of this image, we could use the iconographic method.

But what is iconography? And how do you use the iconographic method to analyze art? The purpose of this essay is to introduce you to the iconographic method used by art historians, and to consider its merits and limitations.

Let’s begin by explaining what the word “iconography” literally means. It comes from two Greek words, eikon (meaning “image”) and graphe (meaning “writing”). Together we get “image-writing,” so the word “iconography” conveys the idea that an image can tell a story. But the study of the iconography of an image is actually more complex, since it involves understanding the specific culturally constructed symbols and motifs in a work of art that can help us to identify the subject matter. To understand the symbols, you have to be familiar with their culturally specific meaning—as in, you need to be “in the know” about agreed upon conventions. The iconographic approach is not particularly interested in the form or style of an artwork.

Let’s return to the image above. This happens to be the DC comic book character Wonder Woman, who is identified by motifs like her red, yellow, and blue clothes; her red boots; and long, dark hair.

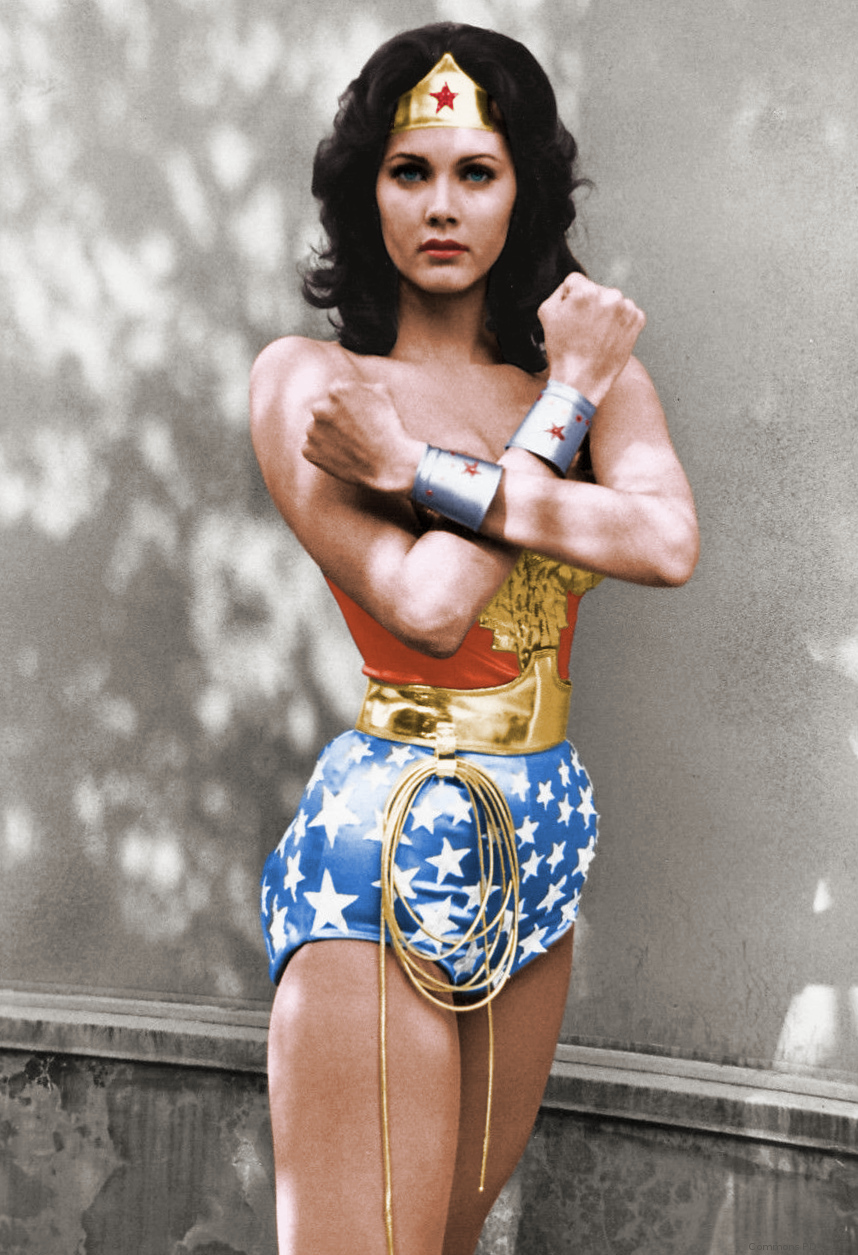

Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman, for the television series Wonder Woman (1975–1979), ABC television (photo in the public domain)

Even when the style of a comic book changes (such as with a new artist) or the story of Wonder Woman plays out on a television screen or as a toy, we are able to identify her. But what happens when we remove most of these shared attributes or motifs? We can’t identify her as easily, rapidly, or securely. Imagine we simply changed the colors of her outfit to green, purple, and orange, or her hair to blonde—we might not recognize her as Wonder Woman any longer.

Beginning to understand the iconographic approach

Let’s consider the iconographic approach using an example from 14th-century Italy. What symbols do you notice that help you to identify the subject?

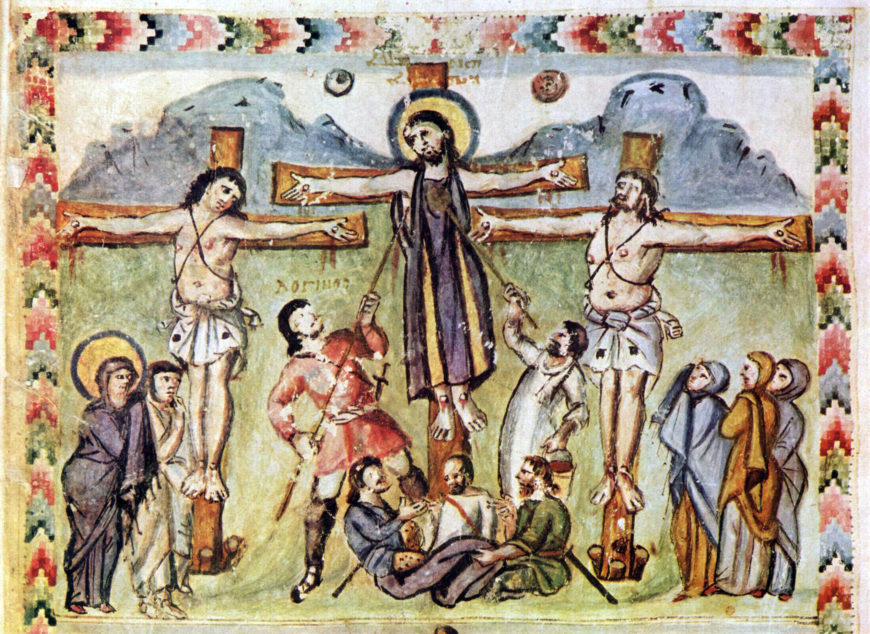

Crucifixion, from the Rabbula Gospels, 586, parchment, 25.5 cm x 33.5 cm (Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence)

If you identified the subject as the Crucifixion (an event described in the Christian Bible as the moment when the Christian savior Jesus Christ is killed on a cross), then you are correct. The symbols and motifs that helped us to make that identification are: a prominent cross, a person hanging on the cross, other figures surrounding the cross, elements that we identify as a landscape, and so forth. This artistic representation of this subject began to be codified by the 5th and 6th centuries, and became standard Christian iconography. Like Wonder Woman, a consistent set of signs, symbols, and attributes allow us to identify the subject matter over centuries and across the globe—no matter the style of the artwork.

Standardizing the symbols and attributes of a subject like the Crucifixion helps viewers identify important figures and events. Consider that in many places throughout time most people couldn’t read, and images played an important role to help diverse audiences learn stories. For instance, in Renaissance Europe, perhaps as many as 95% of people couldn’t read! Maintaining a standardized iconography of the most important moments in Christian theology was one way to help Christian devotees “read” Biblical stories or the lives of saints.

But how do we know how to interpret symbols from the past? One way is to look at written texts (including oral traditions recorded in written form) from the same era as an artwork to see if we can match a particular symbol or motif in the written story with what we are seeing. If we are looking at something made in 14th-century Italy for example, we would turn to texts from this time.

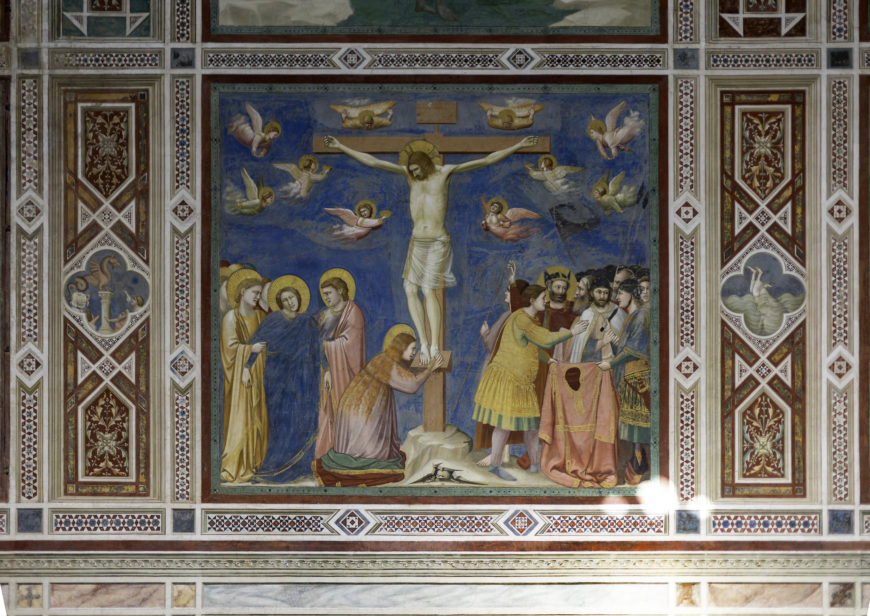

Crucifixion. Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel, 1305–06, Padua, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The steps of the iconographic approach

A German art historian named Erwin Panofsky popularized the iconographic method in the 1930s (largely using medieval and renaissance art of western Europe, such as his famous essay about Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait), and he described three steps:

- Pre-iconographic (primary or natural subject matter)

- Convention and precedent (iconography)

- Uncovering the intrinsic meaning (iconology)

Step 1, the pre-iconographic, is identifying pure forms according to Panofsky. In our image of the Crucifixion, this is observing that we see a person nailed to a cross surrounded by other figures.

Step 2, or convention and precedent, involves finding a text or oral tradition that describes what you are seeing. For the Crucifixion, this could be the Bible (among other things). If in reading the Bible, we read John 19:16–19, we then can make the association between what we saw in Step 1 (a person nailed to a cross) with a narrative.

“So the soldiers took charge of Jesus. Carrying his own cross, he went out to the place of the Skull (which in Aramaic is called Golgotha). There they crucified him, and with him two others—one on each side and Jesus in the middle. [Pontius] Pilate had a notice prepared and fastened to the cross. It read: Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews.”

Step 3, according to Panofsky, uncovers an image’s intrinsic meaning. This step is actually an extension of iconography, and is called iconology. (In fact, it would be more accurate to call this entire approach the iconographic-iconological method, but it is unwieldy and so often shortened to the “iconographic method”; sometimes art historians pair this third step with other approaches). This means beginning to frame the image within its specific time, location, and culture. Perhaps you’ve heard about an artwork’s historical context. This is what Panofsky asks us to begin to consider here.

If we use our Crucifixion example, let’s say we know it dates to the 14th century. This was a time when there were dramatic political, religious, and social transformations. The Black Death ravaged Europe in the mid-14th century. The Franciscan religious order, which originated a century earlier, took their mission to the streets, encouraging people to focus on Jesus’ suffering. They wanted Christians to cultivate a more personal relationship with God. Famine, war, financial instability: many places during this time experienced hardship of some sort. With Panofsky’s third step, we might consider whether these larger historical factors could have shaped or affected the artist’s decision to show the Crucifixion in a certain way. In this version, we see figures in the scene expressing a range of emotions. Their bodies cast shadows, giving the illusion that they are three-dimensional. Was this an attempt to help viewers connect with God during a difficult period?

More practice with the iconographic method

Let’s practice doing the iconographic method with another object.

Step 1: what does this image show on the simplest level?

A standing figure, with a circular disc behind the head.

Step 2: let’s identify the figure by looking at the motifs and symbols

The figure has two arms (although the right one is broken off), two legs, and a face that looks human. The figure has a projection on top of its head, a small raised circle on its forehead, and elongated earlobes, and is wearing what appear to be long robes.

This is the Buddha, and he is shown with his standard symbols: the ushnisha (the cranial protuberance that looks almost like a bun), an urna (the auspicious mark on the forehead), and the elongated ears (caused by the heavy jewelry that he once wore before he renounced his wealth). We not only see these same motifs in other images of the Buddha, but we read about them in texts that discuss the Buddha. The circular disc behind his head is a halo—a symbol used by many religions to distinguish divine figures. The halo is broadly used to signify importance and holiness. If the ushnisha and urna weren’t on this figure, the halo and elongated ears alone wouldn’t necessarily be enough to identify this figure as the Buddha.

Step 3: let’s consider the intrinsic meaning of this sculpture

For this step, we could compare this figure of the Buddha to others made at this time, or even those made before and after it. We might consider the practice of Buddhism at the time it was made. We could even look at art from other cultures that looks familiar to this one.

Comparison of a Buddha from Gandhara with a Roman sculpture. Left: Buddha, c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., Gandhara, schist (Tokyo National Museum); right: “Caligula,” 1st century C.E., Roman, marble (Virginia Museum of Fine Art)

With this particular example, a Buddha from Gandhara, we find that images of the Buddha in an anthropomorphic (human) form did not exist prior to their production in Gandhara and Mathura. We might also find that this Buddha sculpture looks similar to Roman figural sculpture, prompting us to ask why this similarity exists.

While this approach to analyzing art is useful (and fun!), it does have limitations.

Page from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 1200–1521 A.D., Mixtec. Painted deer skin, 19 x 23.5 cm. The British Museum, London, Am1902,0308.1 (BM Add. MSS 39671). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

The limitations of the iconographic method

The iconographic method relies heavily on primary source texts to help us identify symbols and motifs. But what if a culture did not have written texts? What if the textual record is incomplete? Or what if you are so unfamiliar with a certain culture that you don’t even know where to begin to look to identify an object’s iconography?

Take, for instance, a section of the Mixtec codex (book) known as the Codex Zouche-Nuttall. At first glance we can see that there are figures, structures, and perhaps locations. But what do all the other motifs mean? Who might these figures be? The story here is probably less familiar to you, and the writing is pictographic (image writing). We don’t have alphabetic texts that describe in great detail who or what is happening here.

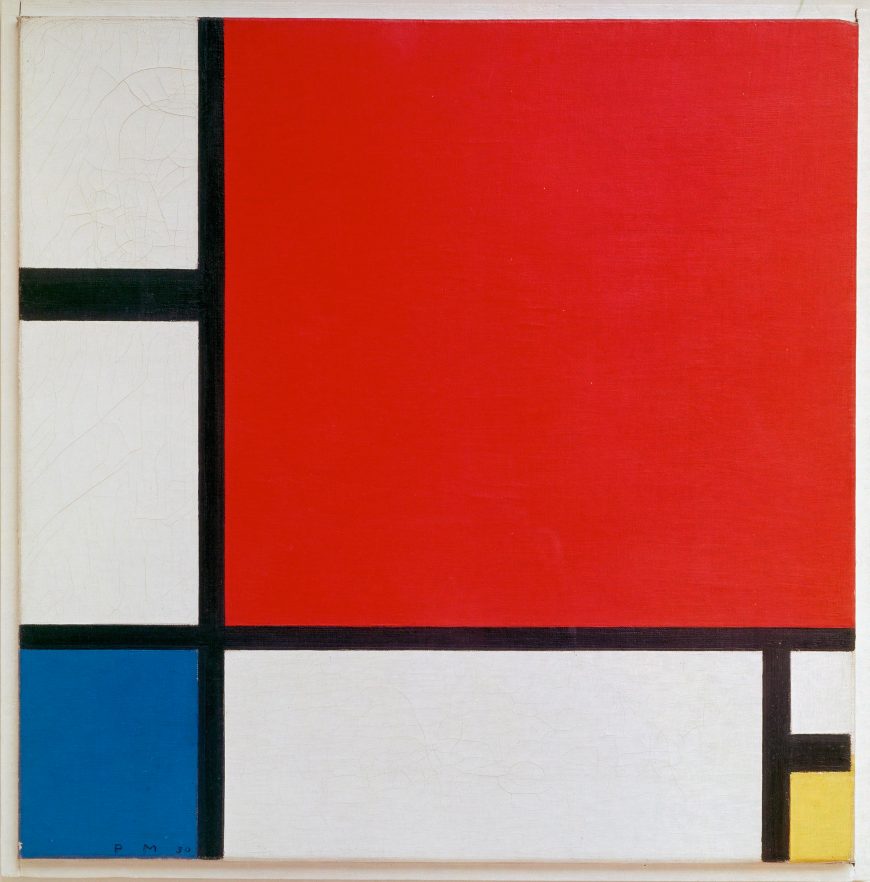

Piet Mondrian, Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow, 1930, oil on canvas, 46 x 46 cm (Kunsthaus Zürich)

Another example that demonstrates the limitations of the iconographic method is Piet Mondrian’s Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow. It is an abstract image without specific symbols. An iconographic analysis isn’t possible, yet take heart! Other methods can help to interpret this painting.

While the iconographic method is useful, other methods of analysis challenge aspects of it. For instance, some scholars would argue that this method relies too heavily on written texts and that it tries to determine a singular or fixed meaning for each symbol and motif, and we know that motifs and symbols can have multiple, shifting meanings. Some scholars also claim that the iconographic approach shifts the focus away from the art itself because the method invites us to spend more time tracing meaning back to written sources rather than focusing attention on the object itself. Another critique of the iconographic method is that it does not do enough to address the social history of an artwork, considering the roles of patrons, viewers, and more. Finally, a limitation of this method is that it positions art as a passive reflection of ideas rather than as an active participant in encoding them.

Nevertheless, the iconographic method can be very useful when used in combination with other art-historical approaches.

Additional resources

Anne D’Alleva, Methods and Theories of Art History (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2005)

Michael Hatt and Charlotte Klonk, Art History: A Critical Introduction to Its Methods (Manchester University Press, 2006)

Erwin Panofsky, “Jan Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 64, no. 372 (1934): pp. 117–27

Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Harper & Row, 1972

Erwin Panofsky, Meaning in the Visual Arts (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982)