Since the 7th century, mosques have been built around the globe. While there are many different types of mosque architecture, three basic forms can be defined.

Sahn and minaret, Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia, c. 836–75 (photo: Andrew Watson, CC BY-SA 2.0)

I. The hypostyle mosque

It makes sense that the first place of worship for Muslims, the house of the Prophet Muhammad, inspired the earliest type of mosque—the hypostyle mosque. This type spread widely throughout Islamic lands.

The Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia, is an archetypal example of the hypostyle mosque. The mosque was built in the 9th century by Ziyadat Allah, the third ruler of the Aghlabid dynasty, an offshoot of the Abbasid Empire. It is a large, rectangular stone mosque with a hypostyle (supported by columns) hall and a large inner sahn (courtyard). The three-tiered minaret is in style known as the Syrian bell-tower, and may have originally been based on the form of ancient Roman lighthouses. The interior of the mosque features the forest of columns that has come to define the hypostyle type.

Ancient capitals (spolia), Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia (photo: ovancantfort, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The mosque was built on a former Byzantine site, and the architects repurposed older materials, such as the columns—a decision that was both practical and a powerful assertion of the Islamic conquest of Byzantine lands. Many early mosques like this one made use of older architectural materials (called spolia) in a similarly symbolic way.

Maqsura, Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On right hand side of the mosque’s mihrab is the maqsura, a special area reserved for the ruler found in some, but not all, mosques. This mosque’s maqsura is the earliest extant example, and its minbar (pulpit) is the earliest dated minbar known to scholars. Both are carved from teak wood that was imported from Southeast Asia. This prized wood was shipped from Thailand to Baghdad, where it was carved, then carried on camel back from Iraq to Tunisia in a remarkable display of medieval global commerce.

Interior of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, Spain, 8th–10th centuries (photo: Timor Espallargas, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The hypostyle plan was used widely in Islamic lands prior to the introduction of the four-iwan plan in the 12th century (see next section). The hypostyle plan’s characteristic forest of columns was used in different mosques to great effect. One of the most famous examples is the Great Mosque of Córdoba, which uses bi-color, two-tier arches that emphasize the almost dizzying optical effect of the hypostyle hall.

Iwan, Ctesiphon, Iraq, c. 560 (San Diego Air and Space Museum Archive)

II. The four-iwan mosque

Just as the hypostyle hall defined much of mosque architecture of the early Islamic period, the 11th century shows the emergence of new form: the four-iwan mosque. An iwan is a vaulted space that opens on one side to a courtyard. The iwan developed in pre-Islamic Iran, where it was used in monumental and imperial architecture. Strongly associated with Persian architecture, the iwan continued to be used in monumental architecture in the Islamic era.

View of three (of four) Iwans, Great Mosque of Isfahan, Iran, 11th–17th centuries, looking toward the south (qibla) iwan (photo: reibai, CC BY 2.0)

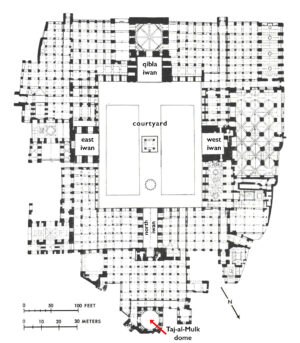

Plan of the mosque, drawn by Eric Schroeder, Architectural Survey, American Institute for Persian Art & Archaeology, 1931

In 11th century Iran, hypostyle mosques started to be converted into four-iwan mosques, which, as the name indicates, incorporate four iwans in their architectural plan.

The Great Mosque of Isfahan reflects this broader development. The mosque began its life as a hypostyle mosque, but was modified by the Seljuqs of Iran after their conquest of the city of Isfahan in the 11th century.

Like a hypostyle mosque, the layout is arranged around a large open courtyard. However, in the four-iwan mosque, each wall of the courtyard is punctuated with a monumental vaulted hall, the iwan. This mosque type, which became widespread in the 12th century, has maintained its popularity to the present.

Iwan, Great Mosque of Isfahan, Iran (photo: reibai, CC BY 2.0)

In this type of mosque, the qibla iwan, which faces Mecca, is often the largest and most ornately decorated, as at Isfahan’s Great Mosque. Here, the mosque’s two minarets also flank the lavish qibla iwan. The Safavid rulers refurbished these walls with new tiles in the 16th century.

Though it originated in Iran, the four-iwan plan would become the new plan for mosques all over the Islamic word, used widely from India to Cairo and replacing the hypostyle mosque in many places.

III. The centrally-planned mosque

While the four-iwan plan was used for mosques across the Islamic world, the Ottoman Empire was one of the few places in the central Islamic lands where the four-iwan mosque plan did not dominate. The Ottoman Empire was founded in 1299. However, it did not become a major force until the 15th century, when Mehmed II conquered Constantinople, the capital of the late Roman (Byzantine) Empire since the 4th century. Renamed Istanbul, the city straddles the European and Asian continents, and, having been a Christian capital for over a thousand years, had a wholly different cultural and architectural heritage than Iran. The Ottoman architects were strongly influenced by Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, the greatest of all Byzantine churches and one that features a monumental central dome high over its large nave.

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, 532–37, Istanbul (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Many Ottoman mosques in the late 15th and early 16th centuries referenced Hagia Sophia’s dome; however, it was not until the masterful work of Mimar Sinan, the greatest Ottoman, if not Islamic, architect, that the domes of Ottoman mosques competed with and arguably surpassed that of Hagia Sophia. Sinan experimented with the central plan in a series of mosques in Istanbul, achieving what he considered his masterpiece in the Mosque of Selim II, in Edirne, Turkey. Built for Selim II, son of Süleyman, during the golden age of the Ottoman Empire, it is considered the greatest masterpiece of Ottoman architecture. It represents a culmination of years of experimentation with the centrally-planned Ottoman mosque.

Dome interior, Mimar Sinan, Selimiye II Mosque in Edirne, Turkey, 1568–74 (photo: CharlesFred/Charles Roffey, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Sinan himself boasted that his dome was higher and wider than that of the Hagia Sophia, highlighting the sense of competition with the earlier Byzantine building. In the Selim Mosque, Sinan distilled previous ideas about the central plan into a simple and perfect design. The interior octagonal space was made more spacious by 8 massive piers that pushed back into the walls, and a rhythmic harmony was created through apertures of small and large arches framed by joggled voussoirs, filling the large space with light and color.

Djingarey Berre Mosque, Timbuktu, Mali, 1327 (photo: MINUSMA/Marco Dormino, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mosque architecture around the world

Minaret, Masjid Menara Kudus (Kudus Tower Mosque), Central Java, Indonesia, 1549 (photo: PL09Puryono, CC0 1.0)

The three mosque types described above are the most common, and most historically significant, in the Islamic world. Despite their common features, such as mihrabs and minarets, one can see that diverse regional styles account for dramatic differences in the colors, materials, and the overall decoration of mosques. The bright blue and white tiled mihrabs of 14th century Iran are a world apart from the muted colors and stone inlay of an Egyptian mihrab of the same century.

Even more, regional differences appear when one looks beyond the central Islamic lands to the architecture of Muslims living in places like China, Africa, and Indonesia, where local materials and regional traditions, sometimes with little influence from the architectural heritage of the central Islamic lands, influenced mosque architecture.

The minaret at Kudus, Indonesia, for instance, reflects the influence of Hindu architecture. The Djingarey Berre Mosque of Timbuktu, in Mali, similarly responds to the pre-Islamic traditions of its own region, utilizing a unique West African style and using earth as the primary building material.

Great Mosque of Xi’an, China, 1392 (photo: chensiyuan, CC BY-SA 3.0)

An early mosque in Xi’an, China, uses a very clearly Chinese style of architecture, but also incorporates more typical elements found in the central Islamic lands, like squinches and a distinctly West Asian-style arched mihrab.

Vedat Dalokay, King Faisal Mosque (Shah Faisal Masjid), Islamabad, Pakistan, 1986 (photo: Ali Mujtaba, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Contemporary mosque architecture

Contemporary mosque architecture often represents a remarkable blending of styles, drawing from diverse architectural traditions to create something recognizably “Islamic” that fulfills all the architectural requirements of a communal mosque and is contemporary in style. In Pakistan, the King Faisal Mosque, 1986, blends contemporary architecture with visual references to traditional forms. The building is strikingly modern, yet plays with the form of the tent structures of Bedouin nomads. This large mosque also incorporates Ottoman-influenced pencil-thin minarets into its modern design.