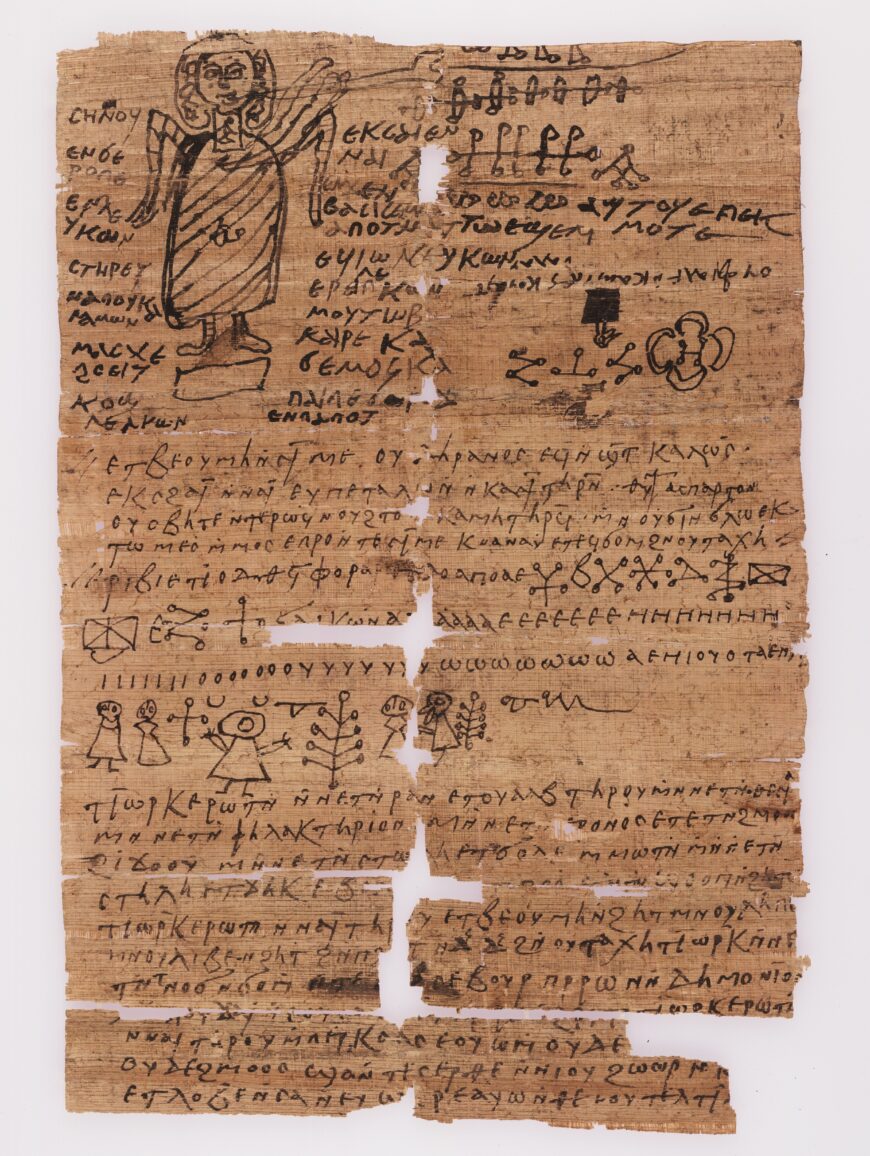

Magical Text (Spell to Acquire a Beautiful Voice), 6th–7th century (Coptic; Egypt), ink on papyrus, 37.3 x 25.4 cm (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven)

What does it mean to pray for a beautiful voice?

In the shifting spiritual landscape of late antique Egypt, between the 5th and 7th centuries, the boundaries between prayer, medicine, and what we call “magic” were fluid, porous, and deeply personal. Communities across the Nile Valley navigated illness, desire, and divine presence with materials ranging from holy oil to amulets, biblical quotations to planetary invocations. One fragment in Yale’s Beinecke Library collection, a papyrus labeled Spell to Acquire a Beautiful Voice, reveals how individuals used written text not only to call upon divine forces but also to reshape themselves, including their voice, body, and soul.

This small piece of papyrus, written in Coptic (the Egyptian language in Greek script) sometime between the 6th and 7th centuries, contains an incantation composed as a love spell. However, unlike more aggressive rituals that seek to control another’s will, this one is inward-facing. It asks not for conquest but for transformation: the gift of a beautiful voice, capable of seducing, persuading, and perhaps preaching. The voice, here, is not merely functional; it is charismatic, radiant, and powerful. To desire such a gift is to understand its weight and to believe that spiritual means can aid in attaining it.

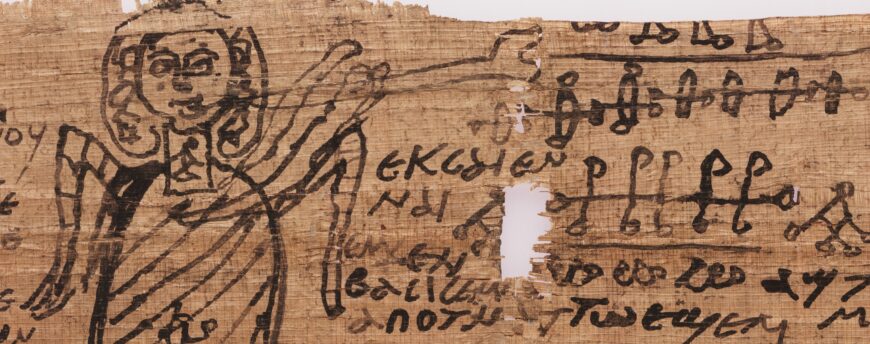

Harmozel (detail), Magical Text (Spell to Acquire a Beautiful Voice), 6th–7th century (Coptic; Egypt), ink on papyrus, 37.3 x 25.4 cm (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven)

Harmozel

The spell opens with a direct invocation to celestial and spiritual beings: the Trinity, archangels, the moon, and the sun. Harmozel, a figure familiar from Gnostic cosmologies and often associated with heavenly intermediaries, is envisioned here as a winged being holding a trumpet. He stands frontally, with both arms raised, perhaps in a gesture of proclamation or power. The wings extend from the shoulders, arched slightly outward, indicating flight or divine transcendence.

The facial features are schematic yet expressive: the eyes are wide, the nose is long, and the mouth is slightly agape, perhaps suggesting speech or breath, highly appropriate in a spell that centers on the transformation of the voice. This focus on the voice may also be reinforced by the depiction of a trumpet-like instrument in the figure’s hand (or next to it), from which a stream of characters appears to emerge. The characters emanating from the trumpet may represent a vocalized blessing, sound made visual, or the sacred language that activates the spell.

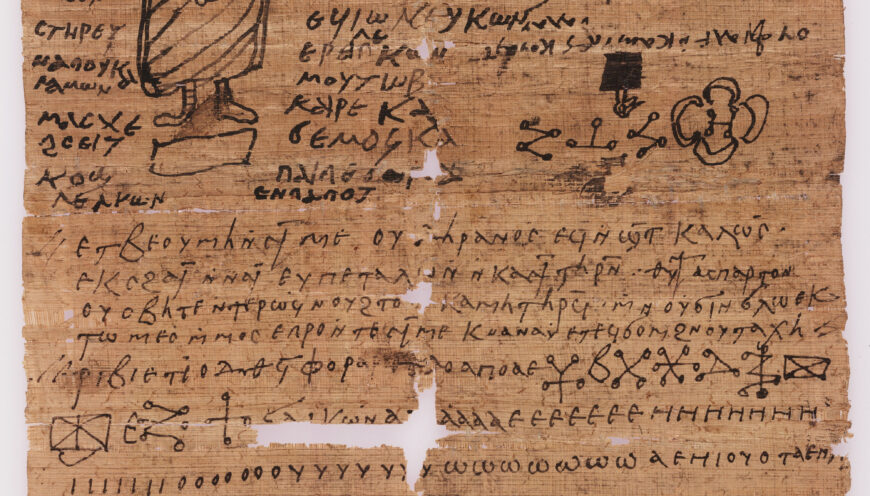

Harmozel (detail), Magical Text (Spell to Acquire a Beautiful Voice), 6th–7th century (Coptic; Egypt), ink on papyrus, 37.3 x 25.4 cm (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven)

The combination of text and image in this manuscript is significant. The visualized Harmozel is not merely illustrative but actively contributes to the spell’s efficacy. His representation makes the invocation tangible, embodying the celestial presence the petitioner hopes to reach. The surrounding glyphs, magical symbols, and textual instructions create a visual and linguistic field where divine presence is made accessible through human action, writing, drawing, speech, and ritual performance.

The petitioner is instructed to prepare specific substances, white dove’s blood, musk, and wine, and to recite the prayer twenty-one times. The setting for this recitation is ritualized: a chalice must be inscribed and used to hold the mixture. Only then, it seems, will the voice be made beautiful.

A Mediterranean magical tradition

While the vocabulary of the spell is drawn from the early Christian milieu, the structure and sensibility of the ritual draw from a broader Mediterranean magical tradition. There are echoes of earlier rites that utilize blood and animal materials, as well as Greco-Roman prayer formulas that invoke celestial alignments. This is not syncretism for the sake of novelty; it reflects the spiritual world in which this text was produced, one where a monk might invoke the archangels in the morning and carry an amulet invoking Seth at night. Rituals were layered, practical, and intimate.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this papyrus is the way it blends divine invocation with embodied intention. The act of writing the spell, preparing the chalice, and speaking aloud are all physical acts. They reinforce the idea that transformation, especially of the voice, requires both spiritual appeal and human effort. Voice, in this framework, is not only sound but presence, power, and charisma. For late antique Egyptians, the voice was also a sign of authority. Prophets, orators, monks, and even healers depended on voice not just to speak, but to manifest divine power.

The spell also illustrates the cultural value placed on performance and speech. In a society where oral tradition remained powerful and where preaching, hymn-singing, and public reading were daily occurrences in Christian and monastic life, having a beautiful voice was not trivial. It was a form of influence. The necessity of such a spell acknowledges that beauty, whether vocal or physical, was not evenly distributed. However, through ritual, it could be requested and even achieved.

Scribe’s handwriting (detail), Magical Text (Spell to Acquire a Beautiful Voice), 6th–7th century (Coptic; Egypt), ink on papyrus, 37.3 x 25.4 cm (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven)

Importantly, the papyrus reveals as much about the spiritual imagination of its user as it does about the scribe who copied it. The handwriting is small, deliberate, and filled with linguistic markers typical of Egyptian Coptic scribal practice. However, the personalization of the prayer, with its specific sensory materials and dramatic ritual setting, suggests it was tailored for individual use. Someone desired this voice. Someone followed these instructions. Someone believed.

In studying this humble text, we are invited to rethink what we mean by “magic.” The term, inherited from Enlightenment-era taxonomies, often implies opposition to religion or rationality. However, this spell, like many ritual texts from late antique Egypt, resists that binary. It is both deeply Christian and ritualistically precise. It borrows from biblical language and Gnostic cosmology, uses blood and perfume as offerings, and treats writing itself as a sacred act. The categories of religion, medicine, and magic collapse into one another, forming a ritual logic driven by need and shaped by belief.

Late antique spirituality

Today, the papyrus is fragmented, a single sheet, brittle at the edges, with ink that has faded in places. Yet, it remains legible. In its legibility, it continues to speak about the desire to be seen, to be heard, and to be transformed. It reminds us that late antique spirituality was not merely about doctrine or dogma; it was about asking the world and the heavens to listen.

The Spell to Acquire a Beautiful Voice is more than a curiosity of religious history. It is a devotional technology that offers a glimpse into the emotional and aesthetic desires of a person who lived in a time of great cultural fusion and spiritual experimentation. Reading it now allows one to hear a voice reaching forward, still seeking, still resonant, still beautifully human.