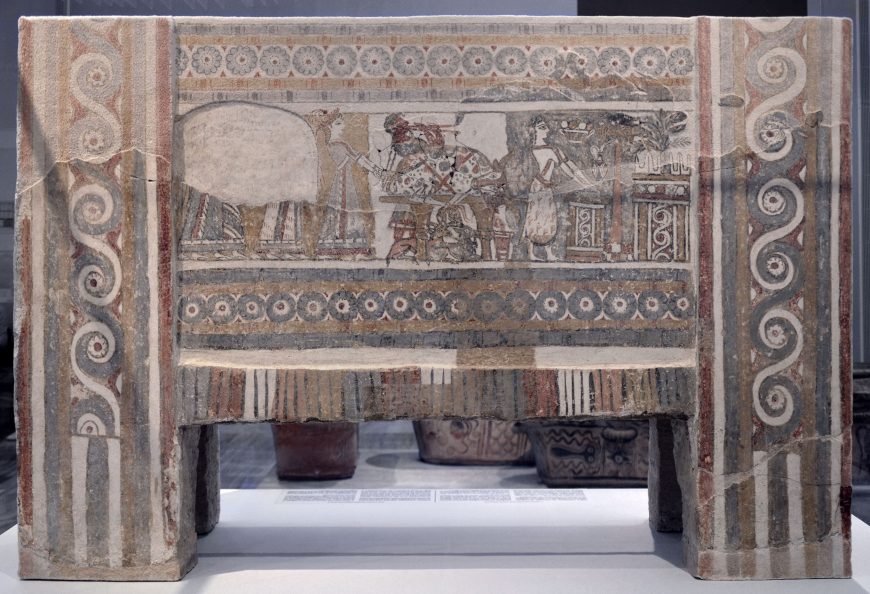

The Hagia Triada sarcophagus at the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (photo: C messier, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A coffin for royalty?

Many images of Minoan rituals are fragmentary and therefore difficult to interpret. There are very few complete, narrative-style representations of religious topics, and the Hagia Triada (also sometimes spelled “Agia Triada”) is the best among them. This sarcophagus was found in 1903 by the Italian archaeologist Roberto Paribeni in Tomb 4 of the hilltop cemetery north of the site of Hagia Triada, a large and wealthy ancient Minoan settlement in south central Crete. Tomb 4 was a family tomb containing the sarcophagus, constructed of limestone, and another large ceramic coffin. The tomb was disturbed in antiquity, but some small burial goods were left behind by the looters: a carved stone bowl, a triton shell, and a fragment of a female terracotta figurine. These remaining grave goods and the elaborate nature of the Hagia Triada sarcophagus has led to the identification of Tomb 4 as that of royalty.

Hagia Triada sarcophagus, c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco, 1.375 x .45 x .985 m (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A story in fresco

The Hagia Triada sarcophagus is the only Minoan sarcophagus known to be entirely painted. It was created using fresco, like contemporaneous wall painting, and illustrates a complex narrative scene, apparently of burial and sacrifice. The object itself is substantial, measuring 1.375 meters (about 4.5 feet) long, .45 meters (about 1.5 feet) wide and .985 meters (about 3 feet) high.

Hagia Triada sarcophagus (detail), c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Zde, CC BY-SA 2.0)

One of the long sides is the most complete and shows a funeral procession of offering bearers and a libation ceremony that features seven figures—two women and five men. From the far left, we see a female in profile facing left, dressed in an elaborate hide skirt and open short-sleeved shirt, holding a vessel in both hands while pouring the contents into a larger vessel which is resting on a stone platform between two poles. The poles are set on richly-veined stone bases and are topped with double axes surmounted by birds. Behind the woman pouring is another woman, and behind her, a man. The second woman, who is elaborately robed and wears a crown of lilies, carries on her shoulders a pole that supports two vessels identical to the one being used for pouring by the first female. The man behind her plays a lyre and is also elaborately robed.

Hagia Triada sarcophagus (detail), c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

The next three people from the left are young men, each bare-chested and wearing a hide skirt. The first two hold bovine statues, one spotted brown, one black; the third man holds a model of a boat. These three men are in composite profile, with shoulders frontal but legs and head in profile, a common Egyptian painting convention. They are also set against a blue background, which is different from the rest of the scene on this side of the sarcophagus. Another man faces these three. He has no feet and looks posed like a sculpture, and it is thought this represents the deceased person. He wears a long hide robe with gold trim.

Between the three men and the deceased is a set of three steps, perhaps an altar, which has some damage at the top. There is a tree above the altar, and it is possible (based on other images of similar altars) that it is supposed to be growing out from the altar itself. Behind the deceased is another structure, elaborately painted with running spirals and inlaid with veined stone. This is thought to be the tomb of the deceased.

Hagia Triada sarcophagus, c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco, 1.375 x .45 x .985 m (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Offerings and altars

On the opposite side of the sarcophagus, there are another seven figures—six female and one male. Beginning again from the left, we are met with a large patch of damage which only leaves the legs and feet of two pairs of women, all with elaborate long robes, moving to the right.

Hagia Triada sarcophagus (detail), c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

A fifth female figure, fully visible, leads them, also well-dressed and wearing a lily crown. She is in full profile, with yellow hair, her arms stretched down towards to the ground. She and the four women behind her are all set in a bright yellow background. Moving to the left, the background color changes to white and against this is a male double-flute player wearing a short blue robe and long curls. He stands behind an offering table on which lies a trussed bull on its side, facing the viewer. Red streaks of blood can be seen coming from the bull’s neck and pouring into a vessel that sits at the foot of the table. Beneath the table are two small goats, possibly awaiting a similar fate.

To the right of this large altar the background color changes to blue; a woman stands before another low altar wearing a hide skirt. This altar is decorated with a red and white running spiral design and on top sits a shallow grey bowl, possibly silver, above which floats in the field a painted beaked pitcher and a two-handled bowl with what appears to be round fruit—possibly all offerings. To the right of this altar is another pole, this one set in a red and white checked base, with a double axe and bird at the top. Lastly, in the field is an architectural structure, also with red and white running spirals and four pairs of horns on top and from which grows a great green tree.

No surface left undecorated

Hagia Triada sarcophagus, c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion)

One of the short sides of the Hagia Triada sarcophagus has two scenes situated one on top of the other, while the opposite short side has only one scene. On the side with two scenes, the top one is almost entirely lost from damage but enough remains to indicate a procession of men in short pointed kilts of richly woven textiles. Beneath this scene is a horse-drawn chariot with an ox-hide carriage in which two women ride, both dressed in elaborate robes and one holding a whip.

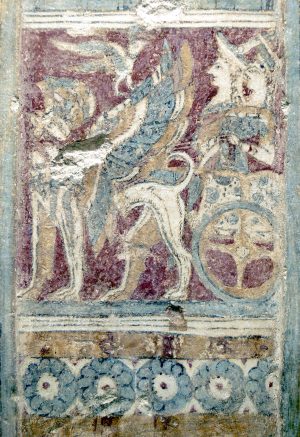

Hagia Triada sarcophagus (detail), c. 1400 B.C.E., limestone and fresco (Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, photo: Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the other short side there is a griffin–drawn chariot with another pair of women riding in an ox-hide carriage also richly dressed and wearing pointed hats. The griffins are multicolored and spread their wings, as if in flight; above them flies a bird in profile, moving in the opposite direction.

Surrounding all five of these scenes on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus are framing elements: rows of rosettes, bands of colors to imitate richly veined stone, running spirals with central rosettes, and colorful striped bands. It is colorfully painted from top to bottom.

Simple story, complex questions

In some ways what we see on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus is simple to understand: women and men in elite dress are busy making sacrifices and preparing the deceased for burial before his tomb. However, looking more deeply, many questions remain. How is it to be read? Is there a prescribed order to the images? What does the change in background color mean? Who exactly are these people—are they all priestesses and priests? Are they mythological characters? Who was the deceased? Was this a special sort of burial, or did everybody get this treatment? These are questions that have yet to be answered with confidence.