Muqarnas from the façade of Masjid-i Imām, Isfahan, Iran, 1612–38 (photo: Farzan95, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The architectural feature known as a muqarnas (pl. muqarnas or muqarnases) is easy to identify but difficult to describe. [1] You could compare it to stalactites, dripping down from a cavernous ceiling above. Or you could say that it resembles a honeycomb, filling the nooks and crevices of an interior space. But the complex geometry of its many cells seems to create a conversation between light and shadow that neither the metaphors of stalactites nor honeycombs capture. To offer my own metaphor, I might say that a muqarnas is the architectural equivalent of an echo, a reverberation of form that is repeated but not replicated.

Muqarnas (detail), Alhambra, Granada, Spain, 13–14th century (Nasrid) (photo: Lawrence Murray, CC BY 2.0)

If one symbol has come to represent Islamic art and architecture writ large, it would be the muqarnas. This is because the muqarnas is a common design feature across the Islamic world and a uniquely Islamic innovation. It was developed in Iraq or Iran sometime in the 9th or 10th century. And from there it spread quickly to places as far away as Spain and India, appearing in mosques, madrasas, palaces, mausoleums, private homes, public fountains, and commercial spaces. When a muqarnas appears outside of an Islamic context, it points to a cultural hybridity or close contact with the Islamic world (for example in the Norman Cappella Palatina). Today, the muqarnas is globally recognized as emblematic of Islamic design.

Art historians agree that muqarnas developed out of the simple architectural element known as a “squinch.”

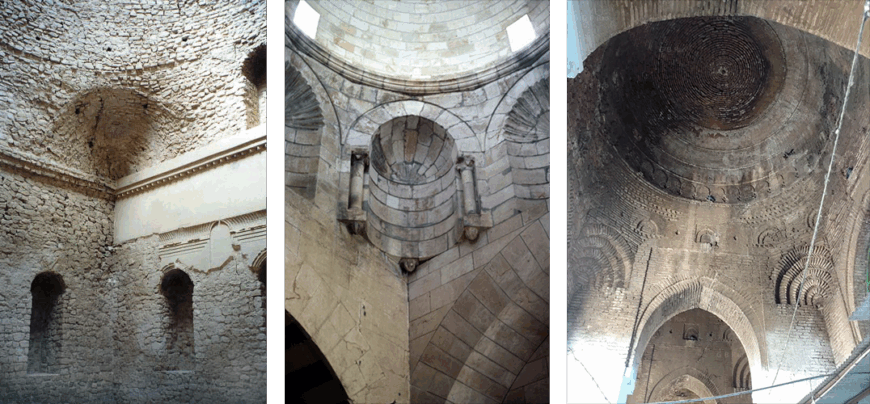

Three examples of squinches. Left: squinch that resembles a smooth concavity from the Palace of Ardashir, Iran, 224 C.E. (photo: public domain); center: squinch that resembles a stylized semi-circular niche from Mashhad al-Husayn, Aleppo, Syria, 12th–13th century, reconstructed in the 20th century (photo: Yasser Tabbaa/AKDC at MIT); right: squinches that resemble tiered steps from Darya Khan Ghumat, Ahmedabad, India, 1453 (photo: Yappe)

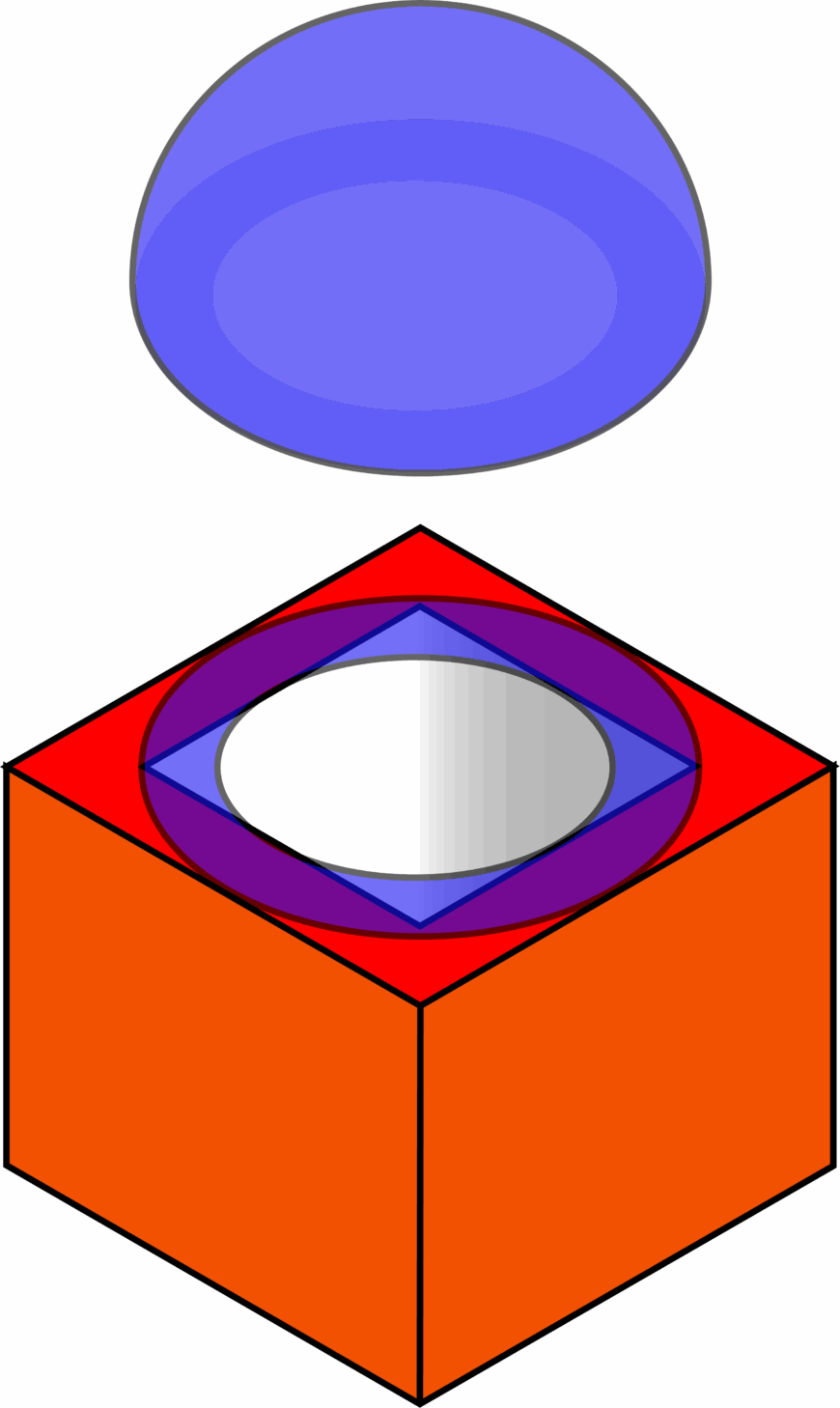

Isometric rendering of how a dome would fit on a square room with no squinches (Courtney Lesoon, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Squinches

A squinch is a solution to the problem caused by putting a dome on a square room (as opposed to putting a dome on a cylindrical room). [2] If a dome is simply placed on a square, the dome’s round edges are left exposed and unsupported at the square’s corners.

Squinches serve as bridges between the round-edged domes and the 90-degree angles below, forming a sort of “zone of transition.” Squinches vary in style, sometimes resembling smooth concavities, niches, or even tiered steps. But they all serve a structural function by transferring the weight of the dome outwards onto the load-bearing walls of the square base. And they provide an opportunity for decorative elaboration too.

View of tripartite “stacked squinch,” Shrine of Davazdah Imam, Yazd, Iran, 1036–37 (Abbasid/Buyid) (photo: akhodadadi, CC BY 3.0)

Sometime in the 9th or 10th century, the muqarnas was developed out of the squinch. Instead of one squinch in each corner of a dome’s square base, builders implemented stacks of squinches in each corner. These stacks of squinches helped to distribute the weight of the dome even better than one squinch could. An extant example of this can be seen in the Shrine of Davazdah Imam in Yazd, Iran. These stacked squinches, with rounded tops and square bottoms, visually integrate the round dome with the square structure below it.

Muqarnas on the underside of a cornice, Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, Cairo, Egypt, 1356–63 (Mamluk) (photo: courtesy of Bruce Allardice © All Rights Reserved)

Muqarnas on a column capital (detail), Apak Khoja Mausoleum, Kashi, China, 17th–20th century (photo: Zossolino, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The versatility of muqarnas

From the simple “stacked squinch,” muqarnas developed quickly into a modular and flexible feature that could be employed in any “zone of transition.” Muqarnas were applied to surfaces such as pendentives, cornices, column capitals, the ceilings of iwans, and arched doorways. In all of these cases, the muqarnas aided in the transition between a horizontal surface (such as the underside of a cornice or the ledge of a capital) and a vertical surface (such as a wall or a column).

Some muqarnas are structural, while others are additively applied to a substrate. Structural muqarnas elements are usually made of brick or stone. Additive muqarnas elements can be made of any lightweight material, including wood, ceramic, stucco, plaster, or even glass mirrors.

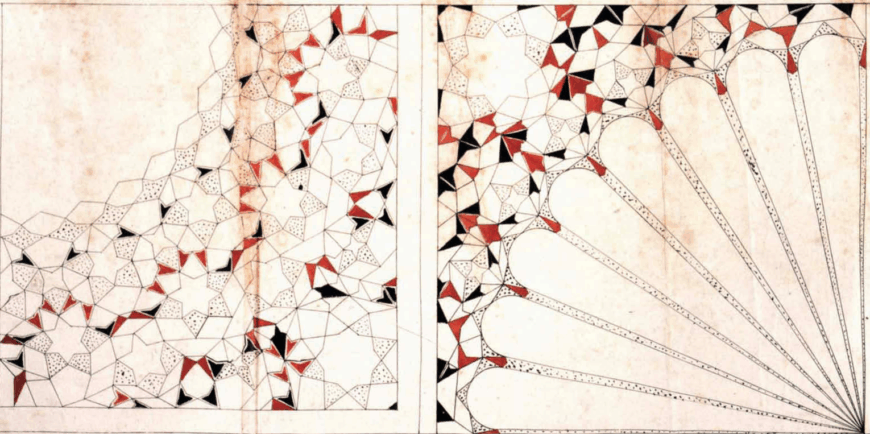

Schematic drawing of muqarnas (detail), from The Topkapi Scroll, late 15th or early 16th century (Iran) (from Gülrü Necipoglu, The Topkapi Scroll, p. 209, plates 6 and 7)

Schematic drawing of muqarnas, from the “Tashkent Scrolls,” 16th century (Uzbekistan), 25 x 24 cm (Abu Rayhan Beruni Institute of Oriental Studies, Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences, TA-46, Drawing #3; photo: Marika Sardar, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Knowledge of muqarnas design was transmitted from master to student via sketches, three-dimensional models, and hands-on training. Detailed drawings of muqarnas patterns that survive from the 15th–19th centuries demonstrate how these artisans planned their three-dimensional patterns on paper. [3] Travel was easy in the medieval Islamic world, and expert craftsmen often traveled far distances for work, bringing with them their tools, techniques, and aesthetic sensibilities.

Interior view of muqarnas dome, Qubbat Imam Dur (now destroyed), Samarra, Iraq, 1085–86 (Abbasid) (photo: Yasser Tabbaa / Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT)

Qubbat Imam Dur (now destroyed), Samarra, Iraq, 1085–86 (Abbasid) (photo: Mustafa Wahhudi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Muqarnas domes

In some especially elaborate cases, muqarnas were used to construct whole domes by repeating and stacking muqarnas cells on top of one another until they met in the middle of the vault.

The oldest examples of muqarnas domes are on tombs, such as Qubbat Imam Dur (or “The Dome of Imam Dur”). This was an 11th-century Abbasid-era mausoleum outside of Samarra, Iraq. Before its destruction in 2014, five levels of muqarnas were visible from the exterior. But on the interior of the dome, these cells seemed to kaleidoscope into a complex three-dimensional geometry intended to impress. One scholar who visited the tomb wrote that the muqarnas here made “the dome appear insubstantial” because “the play of light” on its interior surfaces “dissolved” the dome’s mass. [4]

Interior of muqarnas dome, Turba Zumurrud Khatun, Baghdad, Iraq, late 12th century (Abbasid) (photo: Mustafa Waad Saeed, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Exterior of muqarnas dome, Turba Zumurrud Khatun, Baghdad, Iraq, late 12th century (Abbasid) (photo: Mustafa Waad Saeed, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A similar “play of light” can be seen in the muqarnas dome of Turba Zumurrud Khatun (or “The Tomb of Zumurrud Khatun”). Built by an Abbasid caliph for his mother’s burial, the many tiny perforations in its muqarnas cells allow a constellation of light to move across the interior’s surface. Its tall conical form, which looks remarkable like a beehive, stands out in the cemetery where it is located to mark this particular tomb as belonging to an especially important person.

Muqarnas dome in the Hall of the Two Sisters, Alhambra, Granada, Spain, 13–14th century (Nasrid) (photo: courtesy of Daniel Catalá Pérez © All Rights Reserved)

Long before muqarnas existed, there was a long tradition of domes symbolizing the heavens. With this in mind, art historians suggested more specific meanings for the muqarnas domes. For example, art historian Yasser Tabbaa argued that early muqarnas domes represented an atomizing of the universe, an idea that aligned with developments in Islamic philosophy in that period. [5] And art historian Oleg Grabar cited poetry on the walls of Alhambra that referenced “rotating heavens” to argue that the dome in its “Hall of the Two Sisters” was filled in with muqarnas to convey the spatial impression of “rotating heavens.” [6] While it is difficult to say if these ideas were the intention of the builders or patrons, it is not hard to imagine thinking of “an atomized universe” or “rotating heavens” when you look up into these vaults of seemingly impossible geometry.

Azra Akšamija and Joel Lamere, Unity, 2012, textile installation. Architecture Forum Upper-Austria, Linz, Austria (photo: Future Heritage Lab / Azra Akšamija, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Muqarnas today

The meaning of muqarnas today is clear. Muqarnas has come to represent Islamic art and architecture writ large, even lending its name to the title of a prominent journal of Islamic art history. [7] Muqarnas has become a popular motif in contemporary art and architecture; it is a feature that signals for many something that is “Islamic.”

360 View (c. March 2024) of interior of Mosque of Hassan II, Casablanca, Morocco, 1993 (© Mous Marzouk / Google)

For example, in the 1993 Mosque of Hassan II in Casablanca, Morocco, the French architect Michel Pinseau designed a mosque with more or less the plan of a French cathedral. But, he filled the space with decorative elements that, to him and to his audience, signaled Islamic architecture. First among these elements was muqarnas.

If you visit a mosque in New York, Moscow, Paris, or Johannesburg, chances are you will encounter a muqarnas inside. Perhaps it will drip down from a ceiling like a stalactite. Or it might fill the nooks and crevices of an interior space like a honeycomb. Or even maybe, you might look around and take in the muqarnas as an echo of the forms around it.