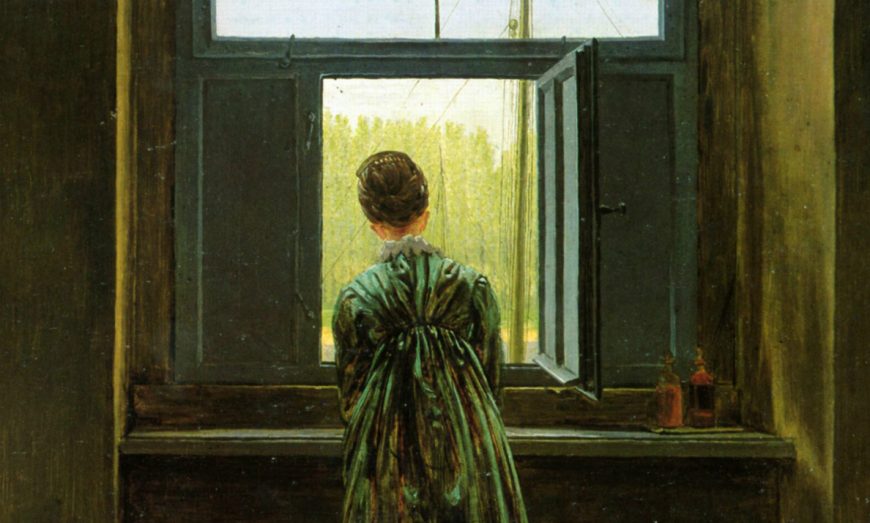

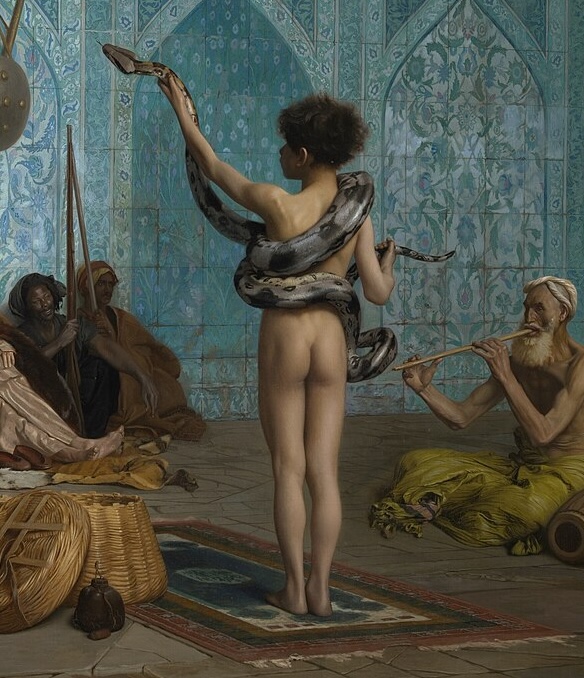

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake Charmer, c. 1879, oil on canvas, 82.2 x 121 cm (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown)

Gérôme’s painting The Snake Charmer is a fantasy masquerading as ethnography. Jean-Léon Gérôme, born 1824 in France, pivoted from a successful career of academic history paintings to Orientalist scenes following an eight-month trip to Egypt in 1856. He sold images of an exoticized, sexualized Orient nebulously located in an undefined “elsewhere” to European and American buyers.

Despite the fictionalized settings and occasionally preposterous scenarios Gérôme depicted, his paintings carried the implication of authenticity. Gérôme made meticulous sketches during his travels to West Asia and North Africa and acquired props such as textiles and military attire. Mixing accurate ethnographic details into otherwise invented scenes won Gérôme praise from contemporary critics for his “scientific” painting. [1] But The Snake Charmer is not a scientific image. It is an exoticized fantasy, not a factual textbook. With smooth paint, titillating subject, and beautiful details, the painting affirmed and reinforced prejudices.

Details surround a lurid scene

The high quality of Gérôme’s paint handling obscures the sordid lowness of the subject. Light bouncing off impossibly beautiful blue tiled walls in a gloomy exterior enchants visually. A sliver of an alfarje wooden ceiling, common in Islamic architecture, can be seen in the upper right corner. Arabic inscriptions on the wall, arched designs in the tile resembling a mihrab and the prayer rug under the standing boy’s feet suggest the scene is set in a mosque though such an activity in a holy setting certainly defies credulity.

Boy with boa constrictor (detail), Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake Charmer, c. 1879, oil on canvas, 82.2 x 121 cm (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown)

In the center of the painting, unclothed, a boy stands with feet together on a prayer rug. A huge boa constrictor formerly contained in the basket to the child’s side coils around his vulnerable naked body. In front of him ten men sit, resting against the tiled wall, staring fixedly at the boy’s front. A half-clothed old man plays a flute to charm the snake. The power difference between the adult men and the young, unclothed child registers sharply. The resemblance of the interior to a mosque heightens the inappropriateness of the scene. It’s absurd even for a palace.

Seated men (detail), The Snake Charmer, c. 1879, oil on canvas, 82.2 x 121 cm (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown)

A plethora of details—intricate woven baskets, the sheen on a metal sword scabbard, a heavy green turban, an improbable metal helmet, uneven stone floor tiles—allow the viewer to gather information about the scene. Like extraneous details in a witness statement, their specificity builds credibility. Gérôme whispers, “it really looked like this.”

Abdullah Frères, Tile in the Imperial Topkapı Sarayı Palace, 1880–93, albumen print (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Some details Gérôme copied directly from photographs in his personal collection. [2] The tiles and floor in The Snake Charmer derive from Abdullah Frères’ images of the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. The believability of the copious details was necessary to sell the fanciful main scene. The details, however, derive from a hodgepodge of locations. The costumes are Balkan. The armor, Persian or possibly Indian. Turkish Iznik tiles provide a setting for snake charming, a street performance practice in Cairo. As Edward Said argued in his influential book Orientalism, Orientalism elides the many diverse cultures of the East into a monolith.

Orientalism

Naked children did not perform snake charming for old men. They certainly did not do so indoors on a prayer rug. The Snake Charmer is no accurate scene, but rather a fiction composed of stereotypes and tropes from what is called Orientalism, a western European idea of the so-called “East.” In visual art, music, and literature Europeans created a version of the Orient of despotic rulers reigning in tyranny, wanton sexual licentiousness, and unchecked violence. [3] Orientalism, like all racisms, contains contradictions: the Orient is portrayed as weak, effeminate and yet strong enough to threaten “Western Civilization” itself.

Far more insidious than a fantasy born of ignorance or misunderstanding, Orientalism eschewed the centuries of trade and cultural knowledge (let us remember the Roman Empire spanned North Africa to Northern Europe) to produce a flexible idea of the “Orient” as a foil to the idea of “Westernness.” Undergirding Orientalism is the idea of alterity. Simply put, alterity allows a subject, here the West, to define the Other, the East, as “that which we are not.” If the West defines itself as good, the East is bad. If the West is strong, the East is weak. Similar crude dichotomies of masculine/effeminate, licit/illicit, industrious/lazy apply. The presumption of the moral and cultural inferiority of the “Orient” conveniently justified Western colonialism. [4]

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Bath, c. 1880–85, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 59.7 cm (Legion of Honor, San Francisco)

Titillating images

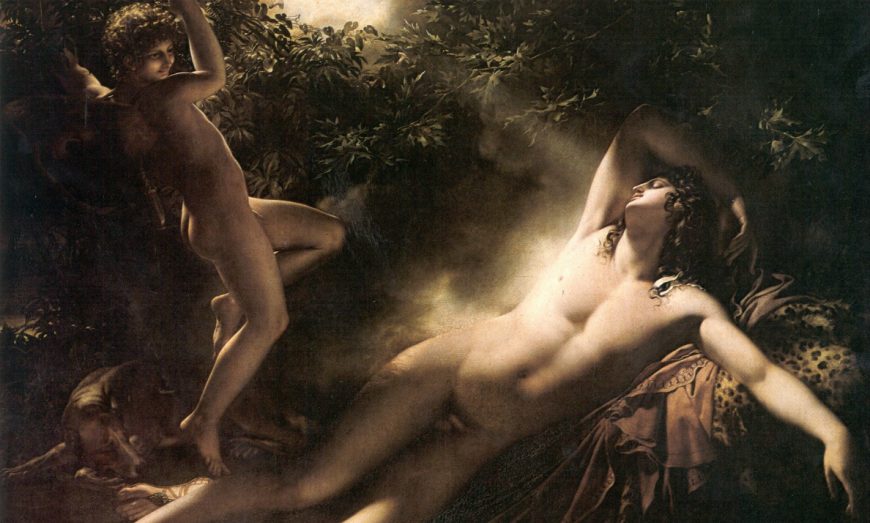

The Snake Charmer, like most of Gérôme’s other Orientalist paintings, titillates the viewer with upset sexual mores. The snake and flute, both phallic symbols, heighten the implications of homoeroticism and pedophilia produced by the uncomfortable tableau. [5] Voyeurism by proxy is offered in Snake Charmer. The swarthy complexions of the gathered men offer the White viewer deniability of his own voyeurism via racial alterity. Images such as The Bath offer direct visual access of privileged, private spaces. With none of the risk of an in-person encounter, viewers could indulge their fantasies of forbidden desires—though it can be argued that the Western viewer mirrors the view of the painted spectators, sharing in the eroticization of the child’s nude body. [6]

Iznik tiles (two of five), circumcision room (Sünnet Odası) exterior but thought to date from an earlier building, c. 1529, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Even though Gérôme’s exoticized scenes were make believe, people fell for them like users falling in love with a chatbot. Details sourced from actual places reassure the viewer that the artist is reporting accurately from his location, but they are less accurate than they appear. We know from a documentary photograph Gérôme owned that he increased the number of broken tiles in the floor. He added a metal hook to the wall for hanging a gun and shield. Decay and militarism are enhanced consistently beyond what can be seen in period photographs owned by Gérôme. [7] The convincing “reality effect” of Gérôme’s paintings makes their editorializing all the more subtle and pernicious. [8] It’s all too easy to accept their purported truthfulness.

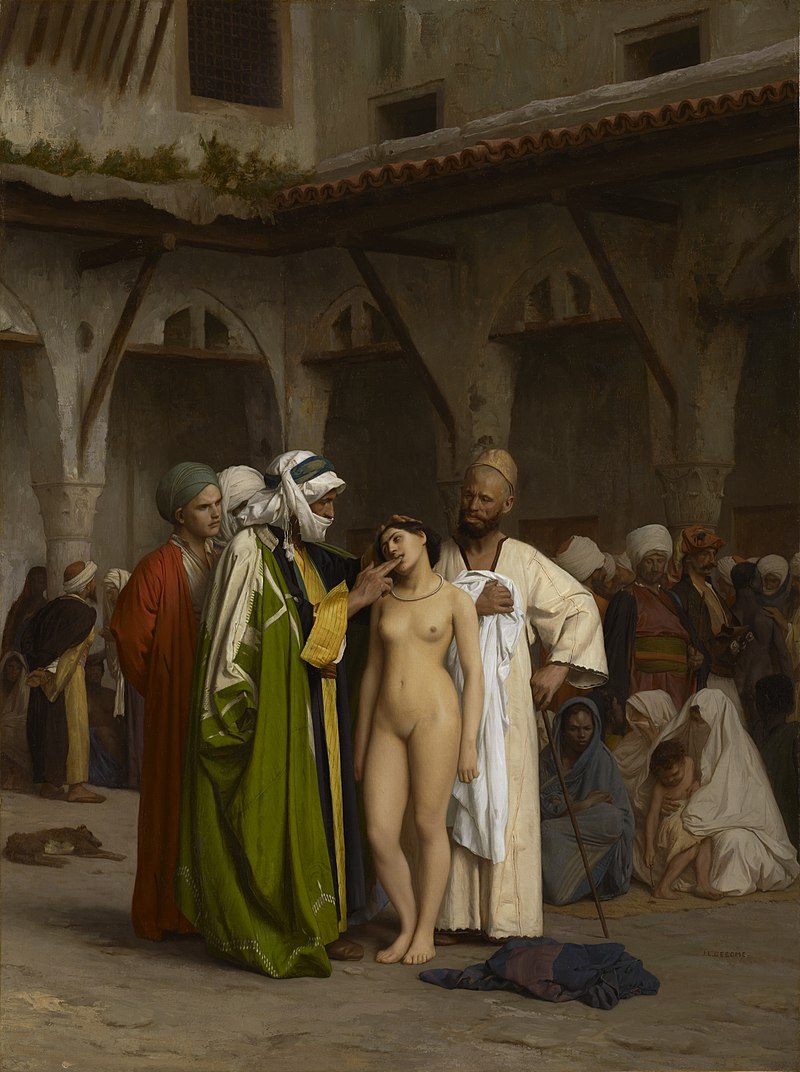

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Slave Market, 1866, oil on canvas, 84.8 x 63.5 cm (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown)

Worldwide circulation

Gérôme’s images circulated widely. In the 1830s he met his future father-in-law Adolphe Goupil, who established the massive global art dealership Goupil & Cie which sold original paintings and printed reproductions. [9] And thus Gérôme’s Orientalist fantasies of dancing women, slave markets, and bath houses traveled around the world spreading Orientalism without haranguing, just the easy sweet taste of pretty paintings. In 1978, The Snake Charmer appeared on the cover of Edward Said’s revolutionary book Orientalism explicitly naming the ideology it once silently spread.