A former orphan, Watson became a wealthy and influential man—after surviving a near-fatal shark attack.

John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, 1778, oil on canvas, 182.1 x 229.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Speakers: Dr. Bryan Zygmont and Dr. Beth Harris

The career of John Singleton Copley is a story that can be told in two distinct chapters. The first part, which extends until 1774, tells the story of his American career, one that primarily unfolds in Boston (with a productive side trip to New York). But when the politics of the impending American Revolution became too unpredictable for a painter who wished to remain as neutral as the situation would allow, Copley sailed from Boston to London. This departure opened the second chapter in Copley’s career, that which takes place in London after a tour of continental Europe. This change in locale, from the Americas to Europe, necessitated that Copley reassess who and what he painted.

John Singleton Copley, Gulian Verplanck, 1771, oil on canvas, 91.4 x 71.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Portraits!

Indeed, an examination of Copley’s oeuvre prior to his departure from Boston indicates that the overwhelming majority of his paintings were portraits. The reason for this artistic output is rather simple: the only real market for art in the American colonies was for portraiture, and Copley, ever the businessman, was willing to provide the art seekers around him exactly what they wanted. His clientele while in Boston comprises the political and economic elite of his day: powerful politicians, elite lawyers, wealthy merchants, and commanding officers amongst many others.

Once relocated to London, however, Copley began to appreciate how different the art market was in England compared to Boston. To be certain, there was a market for portraiture in London. However, the artistic elite in Britain (and elsewhere in Europe) at the end of the 18th century no longer wished to paint simple portraits—pictures that recorded what a person looked like—but instead aspired to paint large-scale history paintings. While these often-immense compositions could, of course, be filled with likenesses, there was the higher, more elevated goal of delivering a morally uplifting message to those who viewed them. Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe is but one example. Painted several years before Copley arrived in London, West not only shows what people looked like—and the image is, in fact, filled with recognizable portraits—he also painted a scene that elevates a British general to a nearly Christ-like level.

Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, oil on canvas, 152.6 x 214.5 cm (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa)

There was no such market for paintings such as these when Copley lived in Boston. But when setting up his London painting studio, Copley was immediately aware that if he aspired to be a great painter, he would be required to turn his artistic talents towards historical compositions. To be certain, Copley completed the occasional portrait during the remainder of his career. When compared to historical compositions, portraits were more quickly painted and could provide the artist with quick access to funds. However, the artist preferred to focus his energies on large-scale history paintings during the remainder of his career. His 1778 masterwork Watson and the Shark is but one example of this change in his oeuvre. Painted less than three years after his arrival in London, Watson and the Shark demonstrates the ways in which Copley had quickly assimilated artistic lessons from his European Grand Tour.

John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, 1778, oil on canvas, 182.1 x 229.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Brook Watson—and the Shark

The Watson of the painting’s title was Brook Watson, a one-time orphan who eventually became Lord Mayor of London. Watson was born in 1735 in Plymouth, England. He was eventually sent to Boston, presumably after the death of his parents, to live with a merchant named Levens, a man who was likely a distant relative. Levens was actively engaged in trade around with the West Indies, and by time Watson was a teenager, he was employed as a member of the crew in one of Levens’s ships. Life changed in 1749, however, when the then fourteen-year-old Watson decided to take a swim while the ship was at anchor in Havana’s harbor. Having discarded his sailor’s woolen garments—clothing that would have been very heavy when wet and impractical when swimming—Watson entered the warm water. Shortly thereafter he was attacked by a shark. Watson’s own account, written in the third person in April of 1778 (when Copley’s painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy), stated that the shark struck three times. “In the first attack, all the flesh was stripped off the bone from the calf downwards; in the second, the foot was divided from the leg by the ancle.” Watson further stated, “at the very instant he was about to be seized the third time, the shark was struck with the boat hook and driven from his prey.” This is the precise moment Copley depicts in Watson and the Shark. Given what we know about Watson and his future life, it is a moment when we know the youth will live, but are surprised that it can be so.

The shark attacks (detail), John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, 1778, oil on canvas, 182.1 x 229.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Indeed, it is a painting filled with drama and action. The composition contains ten figures and a tiger shark, a carnivorous fish so large that its body extends beyond the confines of the painting. Clearly, the main figure of the composition is the fair-haired Watson. He passively floats in the foreground, his feet towards the edge of the painting, his head towards the middle. His left arm is alongside his body while he uses his right arm to reach towards the men in the boat who attempt to rescue him. His left leg kicks towards the surface, while the right leg—already dismembered below the knee—seems to disappear downwards in the water. He looks upwards towards the boat filled with his rescuers in the middle ground, unaware, it seems, of the imminent approach of the shark from the right.

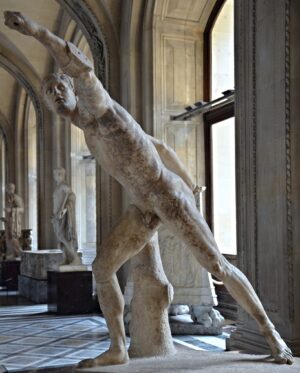

Fighting warrior, known as the Borghese Gladiator, c. 100 B.C.E., 199 cm high (Musée du Louvre; photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Although subtle, the figure of Watson demonstrates the ways in which Copley was incorporating artistic references into his own compositions. If Watson were to stand up, his body would have the same overall position as that of the Borghese Gladiator—one of the most famous of classical works in the 18th century (the version Copley likely saw in the Louvre in Paris is a 1st-century Roman copy after a 3rd-century B.C.E. Greek original). It is also similar to a figure within Raphael’s The Transfiguration, a painting Copley saw at the Vatican. In a letter to his wife, Copley stated that this painting was “allowed to be the greatest picture in the world.” Moreover, Watson’s head, which Copley has painted in profile, is a nearly identical copy of the head of one of the sons in the famous Laocöon statue, a work Copley saw while visiting the Vatican. In fact, Copley so admired this famous work the he own a small cast of it.

But it is not only Watson that demonstrates Copley’s ability to cull from the famous art made before him. Indeed, this composition is filled with artistic references that his audience would have recognized—and most of these references are taken from paintings that are religious in subject. This is not surprising when one considers that one of the themes of Watson’s own life was that of the salvation that can follow a tragic event.

Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1515–16, pen and sepia, washed, 22.3 x 31.75 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Guido Reni, Saint Michael Slaying the Devil, c. 1636, oil on canvas, 293 x 202 cm (Santa Maria della Concezione, Rome)

In regards to imagery, for example, the two men on the left side of boat each extend their right arms downwards to rescue Watson. Copley seems to have borrowed this particular pose from Raphael’s The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, a large-scale preparatory drawing that was then in London (and is now in the collection the Victoria and Albert Museum). Copley seems to have liked this religious narrative, for he also owned an engraving after Peter Paul Rubens’s own Miraculous Draught of Fishes. The standing figure in the boat, the sailor who wears the naval pea coat and is set to strike the shark with the boathook, looks similar to various versions of Saint George (who kills a dragon) or Saint Michael (who casts Satan from heaven). Raphael’s Saint George and The Dragon and Guido Reni’s Saint Michael the Archangel are but two possible influences.

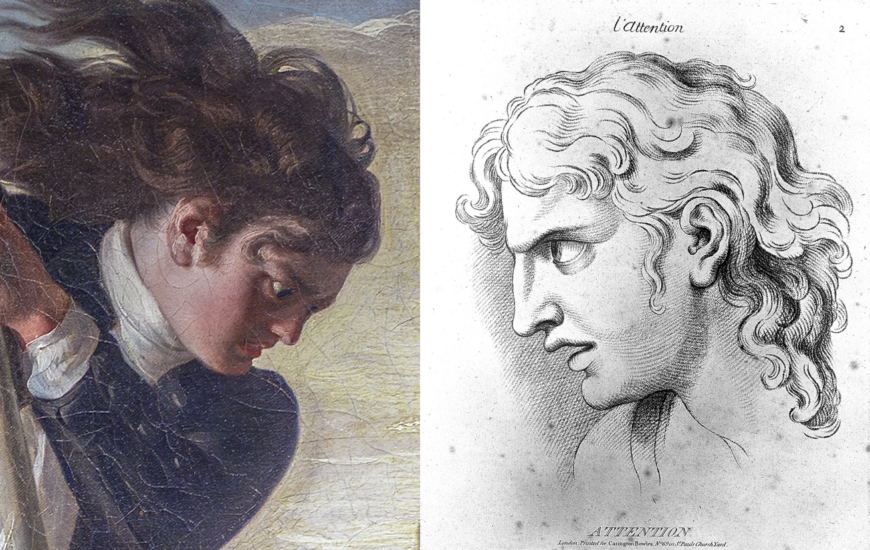

Clearly, Watson and the Shark is an energetic and emotional work. In order to enhance the emotional drama of this event, Copley referenced a well-known treatise of facial expressions. Charles le Brun is most remembered today for his Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions, an artistic treatise posthumously published in 1698 that explored how emotions manifest upon the human visage. Even a century later, artists referred to le Brun’s work to more accurately convey ideas about human emotions.

Left: the face of the man with a boat hook (detail), John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, 1778, oil on canvas, 182.1 x 229.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Charles Le Brun, Bowles’s Passions of the soul, c. 1785 (photo: Fæ, CC BY 4.0)

When applied to Copley’s Watson and the Shark, for example, we can see that the figure at the prow of the boat with the weapon contains the facial expression that le Brun assigns to “Attention.” The sailor at the far left with his furrowed brow and downward turned mouth mirrors that for le Bruns’s “Horrour.” Likewise, the other standing figure in the boat—the man of African descent who holds the coiled rope—conveys le Bruns’s idea of “Compassion.”

Man with boat hook and African American figure (detail), John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, 1778, oil on canvas, 182.1 x 229.7 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

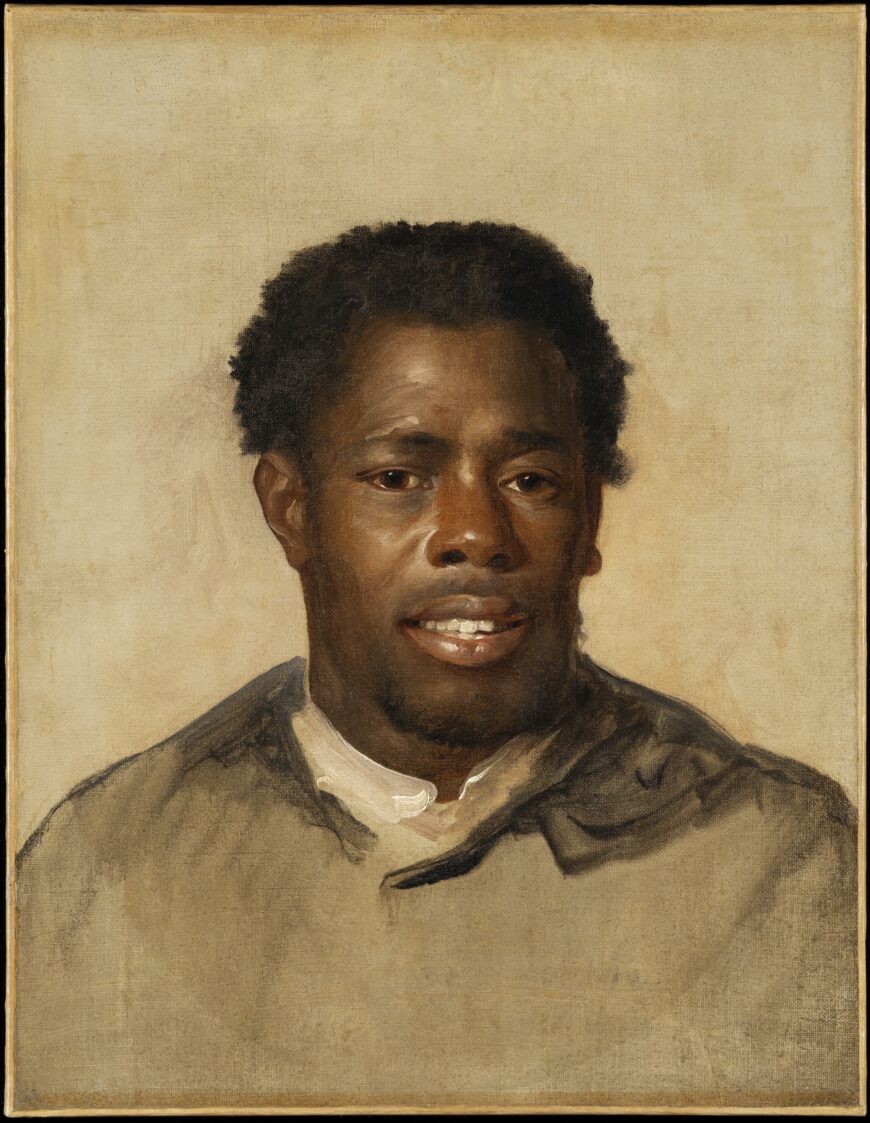

John Singleton Copley, Head of a Negro, 1777 or 1778, oil on canvas, 70.5 x 60.3 x 7.6 cm (Detroit Institute of Arts Museum)

Looking at the faces of the men in the boat, we can see that we have a variety of different kinds or types of people. The young are present, so too are the more elderly. We can say the same about them in regards to wealth. Some seem to be simply dressed sailors. The man standing with the boat hook, however, is dressed in a more affluent way. Note his leather shoes with metal buckles, his silk stockings, and his new navy coat.

The inclusion of the man of African descent standing next to him is an interesting inclusion. Copley has giving this figure a place of particular compositional importance, and he alone holds the rope that links the victim to the boat. Clearly, this is a sympathetic likeness, and whoever the sitter was, Copley seems to have had a particular fondness for him. Indeed, Copley painted him twice. Entitled, quite simply, Head of a Negro when it was sold after the death of Copley’s oldest son, it was described as Head of a Favourite Negro. When compared with other 18th-century (and, to be fair, 19th-century) images of Africans, Copley’s paintings seem both honest and dignified.

Watson must have approved of this depiction, for records suggest that Watson himself had commissioned the work. His will, written in 1803, stipulated that the painting was to be donated to “the Governors of Christs Hospital…as a testimony of the high estimation in which I hold that most Excellent Charity and that they will allow it to be hung up in the Hall of their Hospital as holding out a most usefull Lesson to Youth.” That lesson was clear. Watson, a former orphan himself, had not only prospered, he had become an immensely wealthy man of significant political importance. And he had done all of this on a wooden leg. His story—as pictorially represented by Copley’s painting—was to serve as a kind of visual inspiration for the orphans at Christ’s Hospital.

To this end, Watson and the Shark is similar in some ways to Benjamin West’s earlier painting The Death of General Wolfe. Both were ambitious paintings of a recent event that aspired to morally instruct by the example of a great man. And like West’s painting, Copley’s composition is part fact with some artistic invention. Indeed, although Copley took great care with this painting, it would be inaccurate to say that it depicts a kind of absolute truth. Copley, a transplanted Bostonian living in London, had never visited Cuba, and he was forced to base his depiction of the Havana harbor on engraved prints—not all of which were accurate. Likewise, he had likely never seen a tiger shark, and there are inaccuracies in the ways it is painted. But despite these shortcomings, the painting achieves its goal in requiring the viewer to emotionally respond to a (nearly) tragic event.

As such, Watson and the Shark retains a special place within the history of late 18th-century English Romanticism. In many ways, Watson and the Shark made Copley’s fame in London. Already an Associate of the Royal Academy of Arts when it was exhibited at the annual salon in the spring of 1778, he was elected to full membership less than a year later. It also represents the Copley’s “London-ification” as he moved away from the portraiture that had made his fame in Boston to ambitious historical compositions that more fully embraced the British art market.