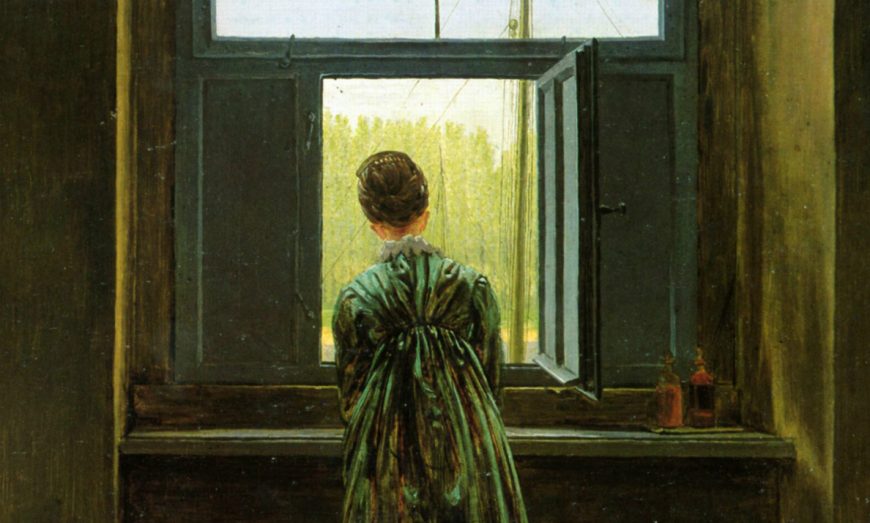

Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Portrait of the Painter Franz Pforr, 1810, oil on canvas, 62 x 47 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

In Johann Friedrich Overbeck’s Portrait of the Painter Franz Pforr, we happen upon a young man who is enjoying a quiet moment at home. The young man, Pforr, looks out at us from the window as a friendly cat nudges his arm. Beyond this pair we see a clean open space, a vase full of flowers, an attractive young woman knitting, and a hawk perched near the ceiling. This scene of domestic comfort ends in a view of a sprawling medieval city and in the distance, a cliff-lined Italianate coast out of another window. Overall, the painting is a charming vision of ideal domestic medieval life. As you look, you may even feel as if you are gaining insight into that time by viewing the scene. However, appearances can be deceiving: the painting was made centuries after the end of the Middle Ages, during a very different time.

Rejecting modernity

In fact, by portraying Pforr as a medieval family man, Overbeck expressed both his and Pforr’s belief that the medieval past was a more appealing time than their own. The two friends lived during a tumultuous time in European history. The Enlightenment had shaken many intellectuals’ faith in church doctrine and the rights of monarchs to rule. Multiple revolutions—most notably the American and French Revolutions—came about partially in response to these shifting worldviews. The French Revolution and its aftermath would touch Overbeck and Pforr directly. The Napoleonic wars of conquest that followed it would lead to the French army occupying their home city, Vienna.

Left: Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Easter Morning, c. 1818, oil on canvas, 131 x 102 cm (Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf); right: Fra Bartolomeo, Noli Me Tangere, c. 1506, oil on canvas, 58 x 48 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

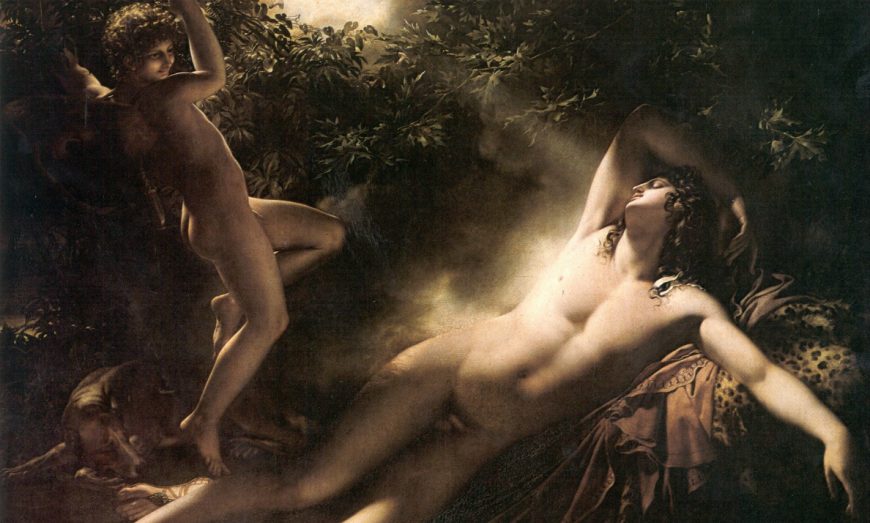

In response to these stresses Overbeck, Pforr, and a collection of other Austrian and German artists formed the Lukasbund, or “the brotherhood of Saint Luke,” after the patron saint of artists. The Lukasbund, who are often referred to as the Nazarenes for their tendency to dress like biblical figures, believed that making art should not just be a job. Instead, it should be an act of devotion. To emphasize this spiritual duty, they took inspiration from medieval art, believing art after the late Renaissance to be too heavily influenced by the secular world. In many cases, the artists strove to replicate the style and poses of medieval and early Renaissance artists as closely as possible. A case in point is Overbeck’s 1818 work Easter Morning, which closely copies Christ’s pose from Fra Bartolomeo’s 1506 painting Noli Me Tangere. The Lukasbund’s devotion to earlier art and culture was so total that, when they fled Vienna to escape the occupying French army, they chose to move into a medieval monastery in Italy.

Left: Pointed arch of the central tympanum at Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Renaud de Cormont, Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France, begun 1220 (Gothic) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Portrait of the Painter Franz Pforr, 1810, oil on canvas, 62 x 47 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

In the portrait of Franz Pforr, art imitates the Lukasbund members’ unconventional lifestyles. Pforr, as suggested above, is immersed in the clothing and material culture of medieval life. Overbeck also includes many hallmarks of Gothic church architecture—the dominant style during the late Middle Ages—in the scene. The window where Pforr rests has a delicately pointed arch. These kinds of arches were central to Gothic church architecture, as their shape redirected the weight of walls in a way that allowed architects to build taller churches. One such structure can be seen outside the window on the other side of the room, directly next to Pforr’s face. Overbeck has also included a thin, serpentine column supporting ribbed vaulting that is reminiscent of Gothic church ceilings in the center of the room.

Skull with crucifix (detail), Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Portrait of the Painter Franz Pforr, 1810, oil on canvas, 62 x 47 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

A world of symbols

Every detail within this Gothic space seems carefully designed to allude to Christian spirituality. The windowsill in the foreground features a carving of a skull topped with a crucifix—a symbol of faith’s ability to triumph over death. On either side of the skull and cross are flowers with a stag and a horse emerging from them. The stag was a common symbol of Christ. The horse, in turn, was associated with the divine authority and judgment of God. Grapes—a common symbol of the Eucharist—ripen on a vine that has attached itself to the window and its carvings. Inside the room, Pforr’s fictional wife sits close by a vase filled with lilies—both the vase and the flowers are common symbols of the Virgin Mary. The falcon above is rich with symbolic associations. In Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy—a favorite text for the Lukasbund—it symbolized religious loyalty. Its position nearby Pforr’s fictional wife also calls to mind its use in another popular Renaissance text, the Decameron, in which it symbolized human love.

Falcon (detail), Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Portrait of the Painter Franz Pforr, 1810, oil on canvas, 62 x 47 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

Taken together, these symbols suggest the omnipresence of faith—and the Christian god—in Pforr’s ideal life. The symbols that surround this version of Pforr and his fictional wife not only highlight the centrality of religion to their lives, but also cast their union as one of purity and piety. The dual symbolism of the falcon, in particular, links together romantic and religious devotion. This connection is key to the message of the work: that pious communities and artistic purity go hand in hand. This point is underlined by the inclusion of two examples of the most pious and community-centric artwork one might be able to imagine: church architecture. The Gothic church in the background appears alongside an Italianate, early Renaissance style church across the road.

Franz Pforr (detail), Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Portrait of the Painter Franz Pforr, 1810, oil on canvas, 62 x 47 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

An influential bond

Overbeck’s symbolic message would have been readily apparent to Pforr, as the two men were close friends who often exchanged ideas about art and life. In fact, the painting is not only an idealized vision of the medieval period, but a sincere wish for happiness from one friend to another. The painting is an example of a common type of artwork called a freundshaftsbild, or “friendship painting.” According to Overbeck, this freundshaftbild was inspired by a dream Pforr had about his own future. By painting the dream, Overbeck metaphorically brought this dream to life. Whether the inspiration of the painting is true or not, the work is a clear statement of Pforr and Overbeck’s close friendship and devotion to supporting the ideals of the Lukasbund.

Pforr died in 1812, never achieving the life his friend painted for him. However, the influence of his and Overbeck’s shared ideals were considerable in the arts. The Lukasbund’s art was an important early phase in Romanticism’s revival of Christian art after the French Revolution. Indeed, medieval subjects would become a touchstone of two developments in French painting of the 1820s through the early 1840s: the troubadour style and the genre historique. In the late 1840s, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood also embraced medieval styles and subjects. Like the Nazarenes, they were uneasy with the modern world and retreated from it by seeking inspiration from the past. This strategy of withdrawal through the use of Christian imagery would resurface at the end of the century, when many Symbolist artists once again turned toward spiritual solace as social norms and technology swiftly changed around them.

Overbeck’s portrait of Pforr, then, demonstrates an enduring tendency in 19th-century European art: the celebration of the past and its culture in times of dramatic change.