Creation myths and form(s) of the gods in ancient Egypt: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 9

Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife

Death Mask from innermost coffin, Tutankhamun’s tomb, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1323 B.C.E., gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones (Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo: Mark Fischer, CC BY-SA 2.0)

When most people think of ancient Egypt, the images that arise are usually pyramids, temples, tombs, and treasure. While daily life in Egypt left little trace archaeologically, tombs and temples are generally well preserved and provide a useful lens for understanding this complex civilization. As dazzling as many ancient Egyptian artifacts, images, and spaces are, and as aesthetically-pleasing as they may be, it is important to remember that most were not produced for a human audience. Instead, these are expressions of the primary driver in Egyptian culture—religion.

Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs created the foundation for their unique, largely theocratic, society. Despite being surrounded in layers of mystery, these beliefs shaped and directed the culture at almost every imaginable level. There were nearly 1,500 deities known by name, and they were believed to not only be responsible for creation but also involved in every aspect of the continued existence of the functioning cosmos. A closer examination of these deities reveals a sophisticated web of connections that only got richer as the centuries passed.

This chapter aims to provide a very basic introduction and general overview of the religious life of the ancient Egyptians. Inextricably linked with their daily lives as well as their afterlives, religious beliefs formed the primary framework around which everything else in this fascinating and long-lived culture grew.

Read essays about creation myths and Egyptian deities

/2 Completed

Temples and priests

View of sphinxes, the first pylon, and the central east-west aisle of Temple of Amon-Re, Karnak in Luxor, Egypt (photo: Mark Fox, CC: BY-NC 2.0)

Interactions with deities at their cult spaces (shrines) began very early in Egypt’s history. From the Predynastic period, the ancient Egyptians established shrines (made initially from reeds and mud) at sacred sites where the gods were believed to dwell. With the founding of the state, subsidized cults developed and the earliest kings of the unified Egypt traveled through the land, visiting cult sites and establishing their relationship with the gods. Over time, these simple structures eventually evolved into massive stone complexes.

These shrines were not merely places of worship—their primary function was to house the gods and serve as miniature models of the perfected cosmos. They provided an interface between the terrestrial and celestial realms. These structures, and the rituals that took place within them, functioned to preserve the proper cosmic order.

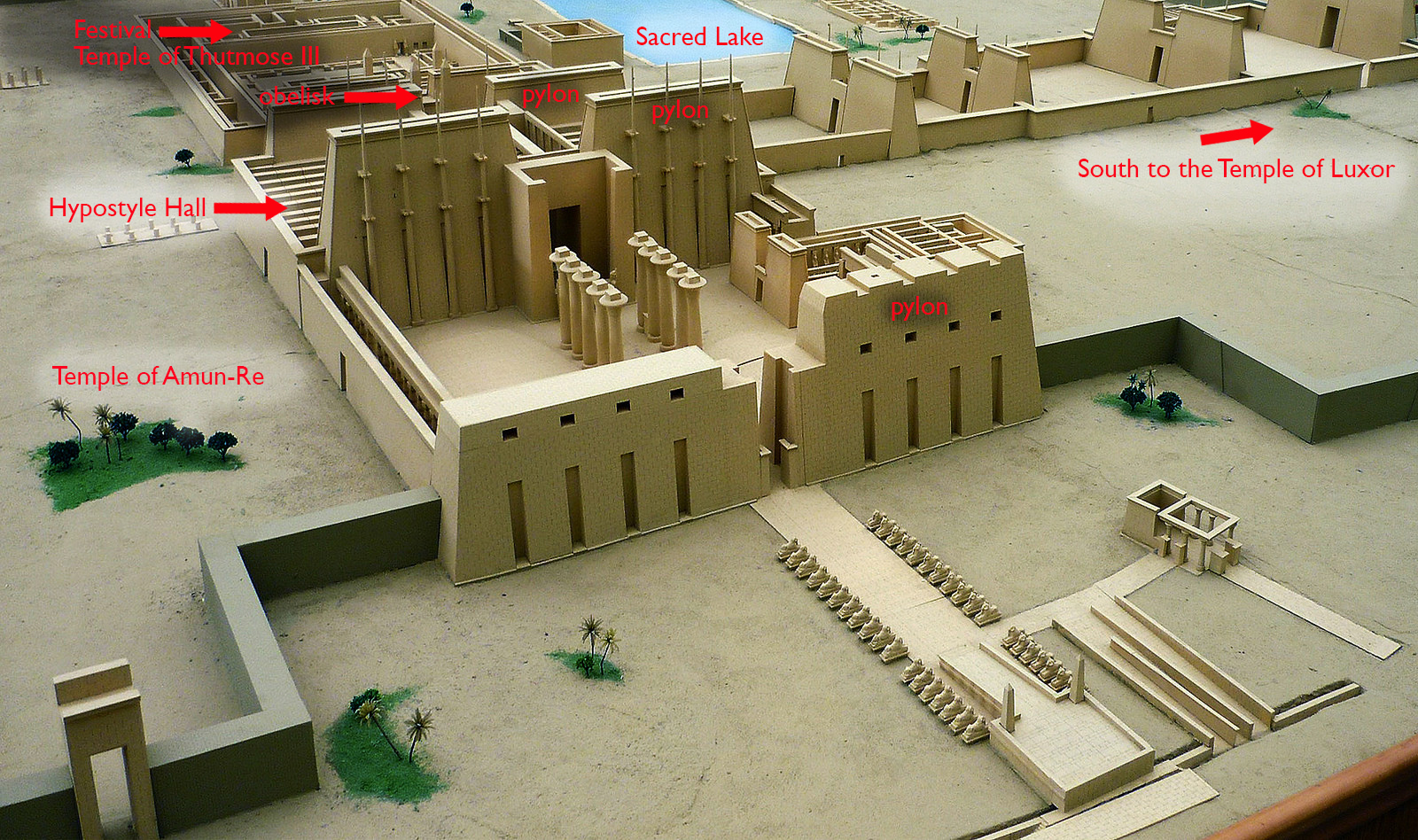

Model of the Precinct of Amon-Re, Karnak (photo: Rémih, CC: BY-SA 3.0)

Temple architecture was explicitly designed to express this idea of the cosmos made manifest. This included temenos walls that separated the everyday world from the sacred space inside, pylon gateways shaped like the hieroglyph for “horizon,” an axial processional way that mirrored the path of the sun, and the dark, small, hidden space of the inner sanctuary that represented the mound of creation.

Column scene of Ramesses II burning incense and pouring libation, in the Hypostyle Hall, Karnak, Thebes

Carved on the walls were scenes depicting ritual actions being performed before the gods; in nearly all cases, the king was shown as chief officiant. These reliefs assisted in the perpetual enactment of the necessary rituals that kept the gods provisioned and ensured the perpetuation of the cosmos. By keeping the gods satisfied and serviced through the daily rituals that tended to their basic needs, they in turn were willing and able to sustain the functioning of the universe.

While in theory the king and the deities were the sole participants in the daily ritual cycle, in reality this function would have been served by priests. Priests acted as the king’s surrogates within the temples and performed the required daily cult activities. While in earlier periods temple service was performed as one of the rotational duties expected of local officials along with their more secular tasks, by the New Kingdom temple activities were undertaken by a professional, often hereditary, priesthood.

Cult Image of the God Ptah, c. 945–600 B.C.E., Third Intermediate Period–early Dynasty 26, lapis lazuli, height of figure 5.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The focal point of the daily rituals was a cult image of the deity that was kept in the inner sanctuary of the temple. Often crafted from precious materials like gold, silver, and lapis lazuli, very few of these cult images have been preserved (they are small, so easily transportable). They were not viewed as gods themselves, but instead provided a ritually perfected place to house their spirits or manifestations. The daily rituals indicate that these cult images of the deity were treated almost as though they were alive. Rituals included washing the statues, anointing them, clothing them, adorning them with jewelry, censing them, and providing offerings of food and drink before returning them to their shrines again.

Read essays about temples and priests

/3 Completed

Personal ritual and daily magic

Kings Hatshepsut (front) and Thutmosis III (rear) perform rituals before the divine bark of Amun during a festival procession. Red Chapel of Hatshepsut, Dynasty 18, Karnak Open Air Museum (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Most people primarily interacted with the official cults during public festivals and processions that served to rejuvenate the gods. These festivals included removing the cult image from its shrine, often placing it on a special boat-shaped palanquin (known as a bark), and processing it along proscribed routes to visit other deities in their temples or to certain sacred locations. These public processions permitted the general population, which was denied access to the temple proper, to “interact” with their gods.

The general population could also gain access to the temple gods via special shrines placed outside the temple walls (often at the rear of the structure, lined up with the inner sanctuary) and at the feet of the colossal statues that stood at the front entrance and served as mediators.

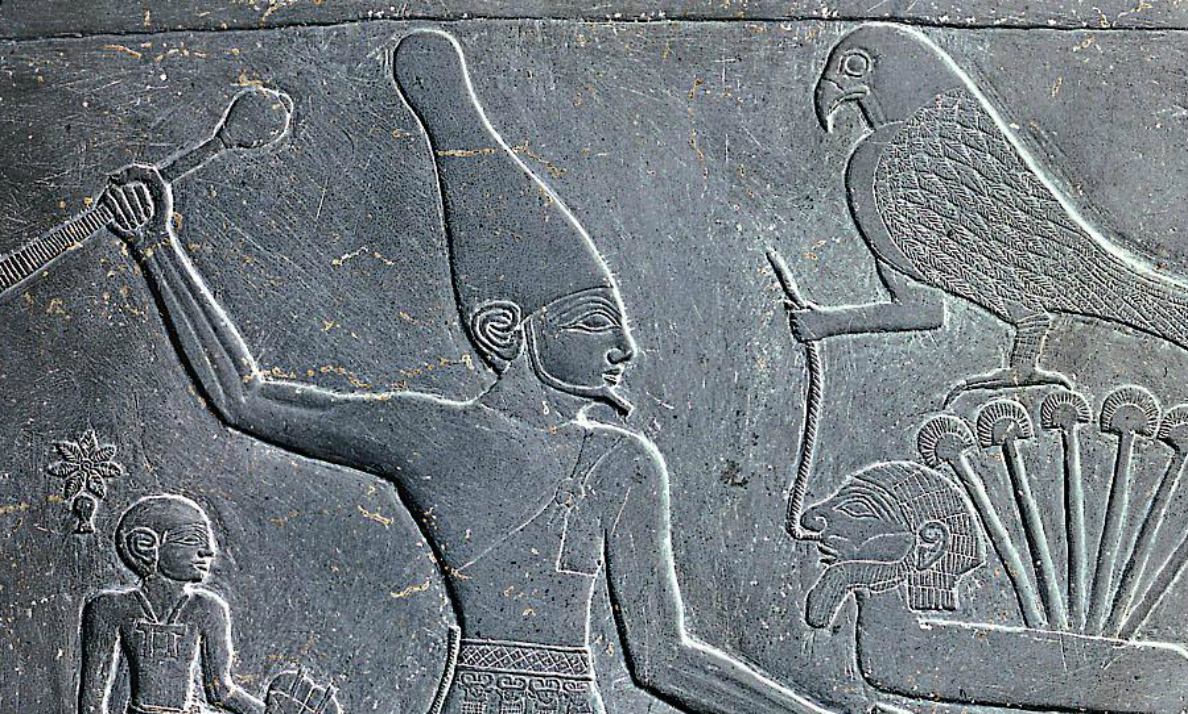

Palette of King Narmer, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., Predynastic Egypt, greywacke (slate), from Hierakonpolis, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

While the vast majority of the population played no role in temple rituals, they could engage with formal religious spaces by presenting votive offerings as an expression of piety and dedication. Wealthy individuals donated statues of themselves presenting offerings to be placed in the temple. Other votive objects included stelae, statuettes, food offerings, mold-made faience amulets, and mummified sacred animals. Vast numbers of such votive objects were donated in temples over the millennia.

Many of these objects survive because after a period of time votive offerings would begin to fill the temple space, which then needed to be cleared out to make room for new offerings. Having been dedicated to the gods, these objects could not simply be discarded; instead, large collections were ritually buried on the temple grounds. Several examples of these ritual pits have been discovered and excavated. Referred to as caches, they preserved many exquisite statues as well as some of the most important ceremonial objects to have survived from antiquity—including the extraordinary Narmer Palette.

Apotropaic wand showing Bes and Taweret (both of whom are associated with childbirth), 12 dynasty, hippopotamus ivory, Thebes, Upper Egypt, 37 cm long (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The wider concept of personal piety seems to have emerged during the First Intermediate Period (c. 2150–2030 B.C.E.). This practice permitted more direct divine access for common people via small local shrines, developing alongside the state temples, where prayers could be offered and votive objects dedicated. Many Egyptians also venerated personal deities in household shrines. Houses excavated in the New Kingdom village of Deir el-Medina provide numerous examples of such shrines, with niches where images of deceased relatives and household deities like Bes and Taweret were venerated. These deities were believed to have the ability to ward off evil and also appear in the form of wearable amulets intended to serve the same function.

Read essays about personal ritual and daily magic

Apotropaic wand: a powerful example of daily magic connected with protecting pregnant women and newborns.

Read Now >

House Altar depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Three of their Daughters: a beautiful stelae from a household shrine at Amarna, where the royal family served as the objects of worship.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Mortuary Practices

Body and identity

Funerary beliefs developed that required the body of the deceased to be preserved and kept identifiable so the spirit could return to it. In the earliest burials, bodies were dried out by desiccation in the arid desert conditions; some of these natural mummies are quite well preserved. The processes used to preserve the body became quite complex. Performed by a special class of priests, there were different levels of mummification depending on economic status, with a wide range in cost and overall success.

Watch a video and read essays about the body and identity

Tutankhamun’s tomb (innermost coffin and death mask): The magnificent inner coffin of Tutankhamun presented him as a god, who were believed to have skin of gold and bones of silver.

Read Now >

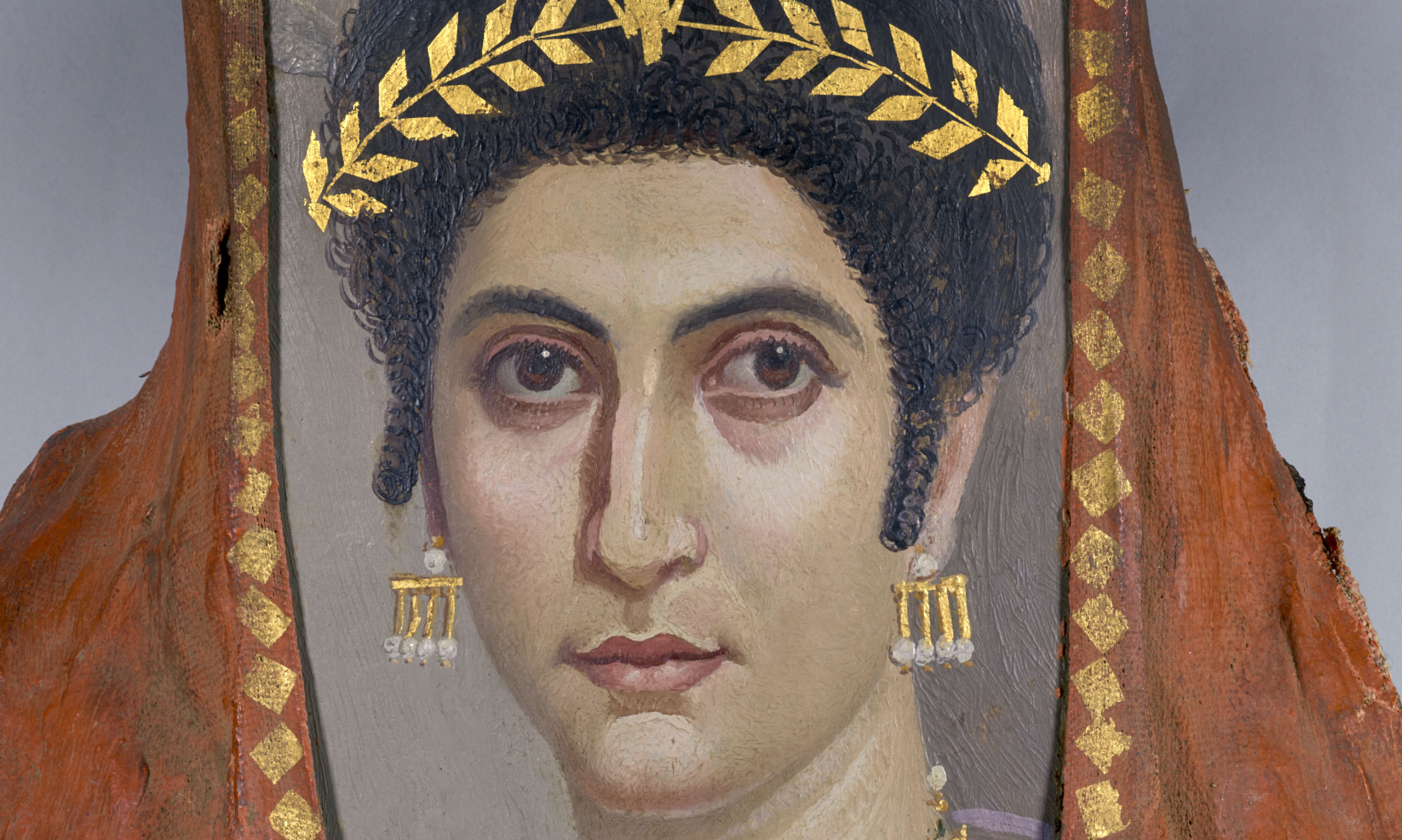

Egyptian mummy portraits: Late Ptolemaic and Roman period mummies often included painted portraits of the deceased so they could be easily identified.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

Tombs

The earliest burials were simple pits dug out of the sand in which the body and a few grave goods (such as pottery, basic palettes, and tools) were placed. Over time, these became larger and more elaborate, eventually including multiple rooms with plaster walls and complex painted scenes. The range of grave goods and the quality of the burial varied considerably depending on the economic status and wealth of the deceased.

Interior view of standing enclosure of Khasekhemwy (Shunet), a large rectangular enclosure that probably contained small shrines inside for ritual function. Early Dynastic, Abydos, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Most Egyptian tombs had two primary components: 1) a sealed-off subterranean chamber containing the body and grave goods, and 2) a superstructure with a chapel that could be visited by family and friends to perform rituals and leave offerings.

View of the South Court after leaving the entrance colonnade, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Royal mortuary monuments of the Early Dynastic period (c. 3000–2686 B.C.E.) at the site of Abydos consisted of a large mud brick ritual enclosure near the cultivated land and a subterranean tomb dug several kilometers to the west near an opening in the desert cliffs believed to be the entrance to the netherworld. With Djoser at the beginning of the Third Dynasty, these mortuary features were combined into a single, massive complex at Saqqara.

Pyramid complexes of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2150 B.C.E.), including the well-known Great Pyramid at Giza, consisted of several elements besides the pyramid itself, including multiple temples, stone-lined causeways, smaller subsidiary pyramids and chapels, and buried boats.

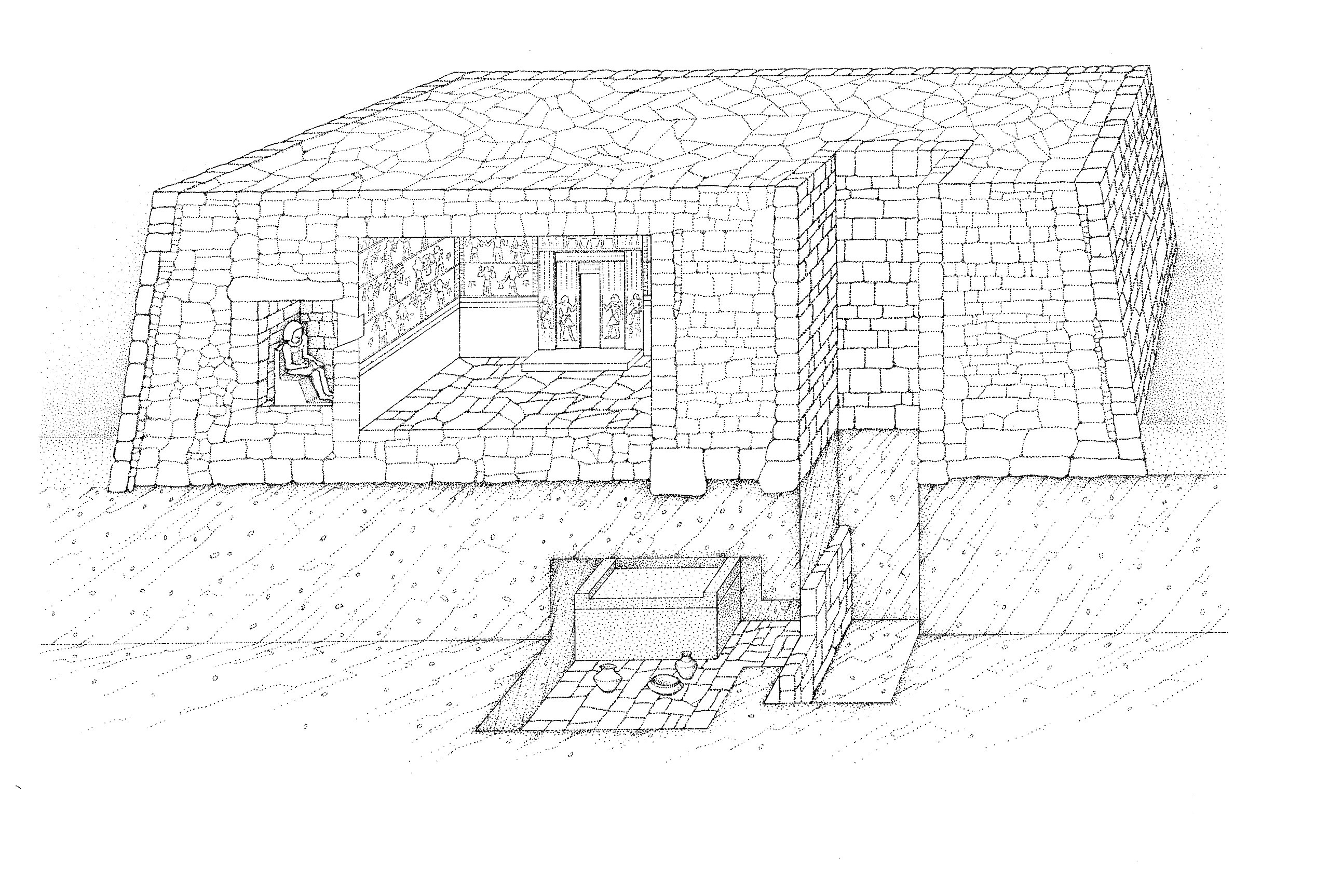

Drawing of Vizier Ptah-Wash’s mastaba, from Vesiren Ptah-wash’ sjæledør og hans sørgelige skæbne by Elin Rand Nielsen, vol. I: Nationalmuseets arbejdsmark (Nationalmuseet : Poul Kristensens Forlag, 1993; CC0)

Elites were buried in large cemeteries that surrounded the tombs of their kings, in flat-topped brick structures known as mastabas. Nearly solid, these private tombs consisted of the sealed burial, below ground, and a chapel cut into the side of the mastaba for the veneration of the deceased.

Read essays about mortuary complexes and tombs

Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Sphinx: another pyramid complex guarded by the famous sphinx at Giza.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

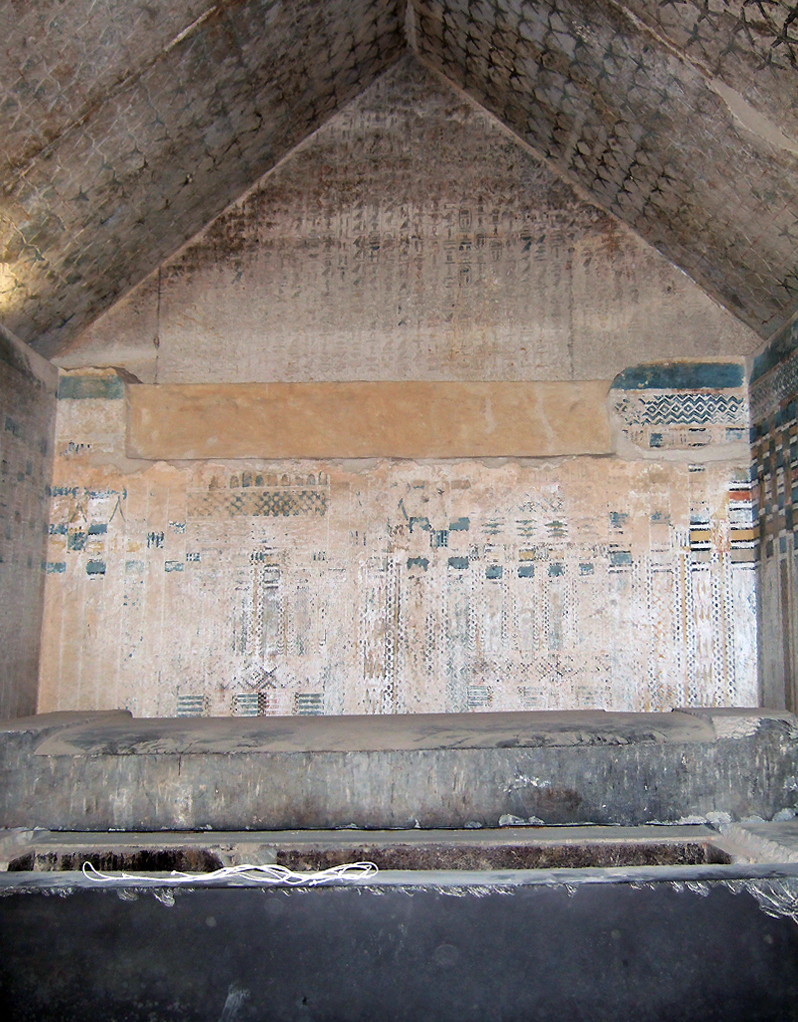

King Unas’s burial chamber displaying the sarcophagus, royal palace facade motif, west gable inscriptions, and starry ceiling (photo: Vincent Brown, CC BY 2.0)

Royal burial chambers came to be covered with lines of text by the Fifth Dynasty, such as those in the pyramid of King Unas. Pyramid Texts, as they are now known, were among the earliest religious writings on the planet. This collection of recitations and instructions was designed to help the deceased in their afterlife journey.

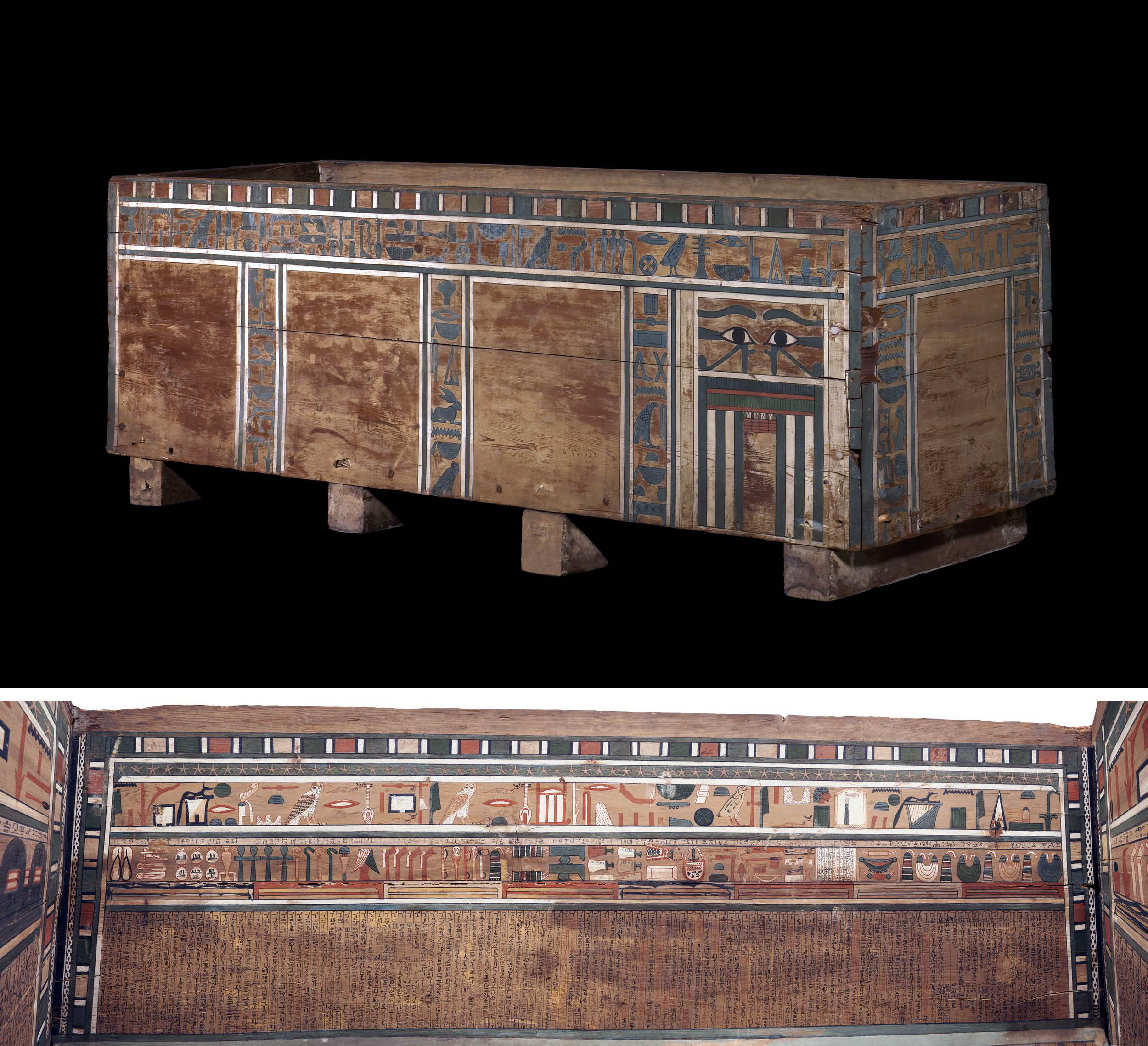

Painted wooden inner-coffin of Seni with lid, c. 1850 B.C.E. (12th dynasty), painted wood, findspot: Deir el-Bersha, Egypt (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Royal pyramid tombs of the Middle Kingdom did not contain inscriptions. These complexes, with their elaborate mortuary temples, are unfortunately not well preserved. This was largely due to the construction methods used during this period, where the pyramids had a core of mud brick encased in stone blocks. Later looting of the casing stones resulted in extreme weathering of the exposed mud brick. Many private burials were better preserved and included painted coffins covered with texts and scenes intended to aid the deceased in the afterlife. This collection of funerary literature is now referred to as the Coffin Texts.

Valley of the Kings and Memorial Temples on the edge of cultivation, Thebes, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

During the New Kingdom, royal tombs were carved deep into the hills of western Thebes, in a place now known as the Valley of the Kings. These hidden burials were conceptually paired with large memorial temples constructed closer to the land of the living on the edge of the cultivated land. These structures were used for the king’s mortuary cult, providing the deceased ruler with all the offerings and necessary rituals to ensure their idealized continuation in the netherworld.

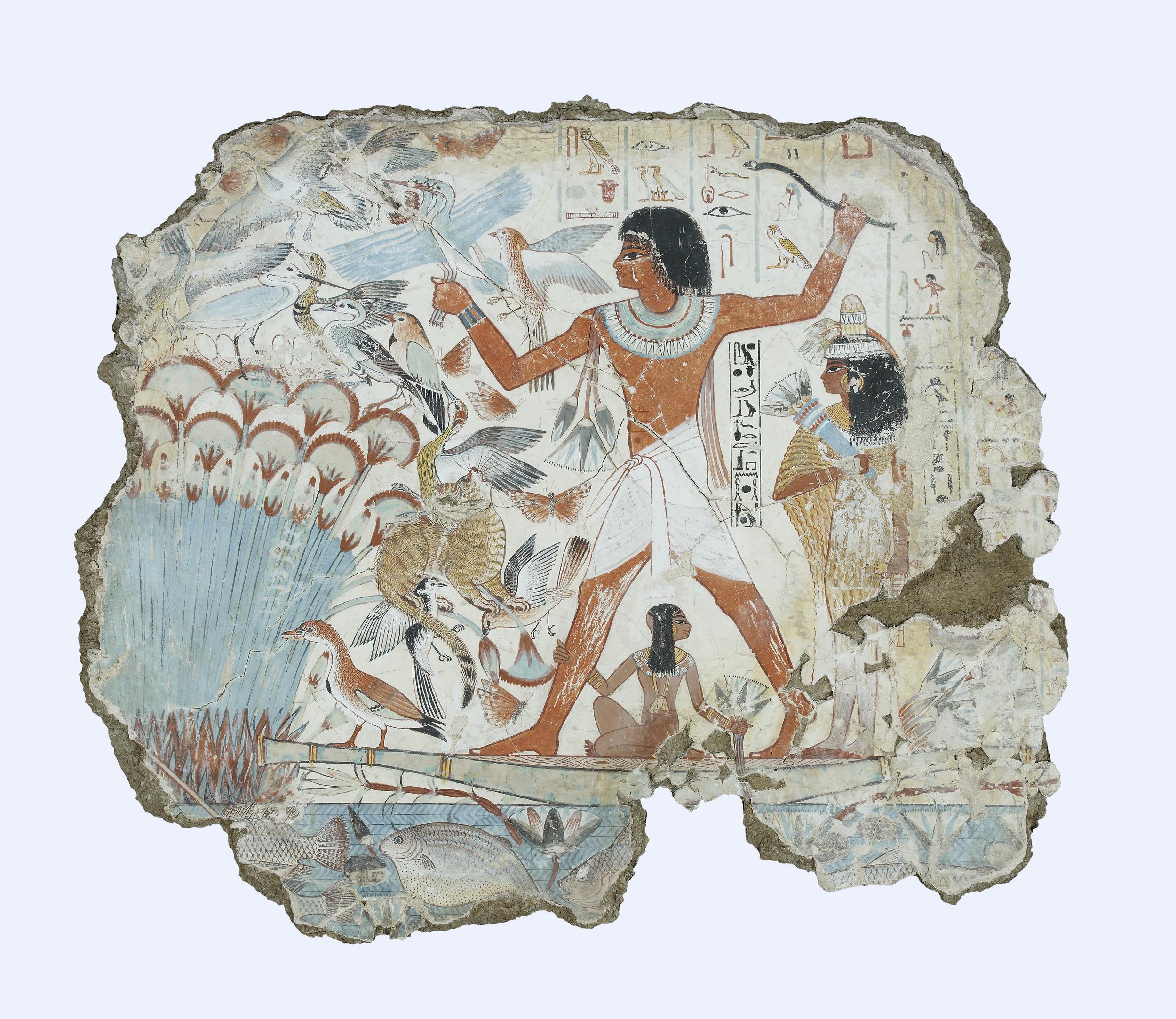

Nebamun fowling in the marshes, Tomb-chapel of Nebamun, c. 1350 B.C.E., 18th Dynasty, paint on plaster, 83 x 98 cm, Thebes © Trustees of the British Museum

Private tombs in the New Kingdom continued to include elaborately decorated chapels with scenes and texts related to important events from the life of the deceased and ritual scenes designed to provide for them in the afterlife. Some preserved scenes depict lively and vibrant representations of their life on earth.

Learn more about mortuary texts and New Kingdom tombs

Mortuary Temple and Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut: The Memorial Temple of Hatshepsut, with its unusual terraced design, is one of the most elegant structures from the ancient world.

Read Now >

The tomb-chapel of Nebamun: Nebamun’s tomb is full of energetic scenes from his life as a New Kingdom official.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Journey of the Deceased

After the funeral rites and burial, the deceased began their netherworld journey toward the land of Osiris, aided by mortuary texts like the Book of the Dead that would be included in their tomb. These texts provided a sort of road map and specified the spells needed to successfully traverse this dangerous realm and get past the guardians and gatekeepers they encountered along the way.

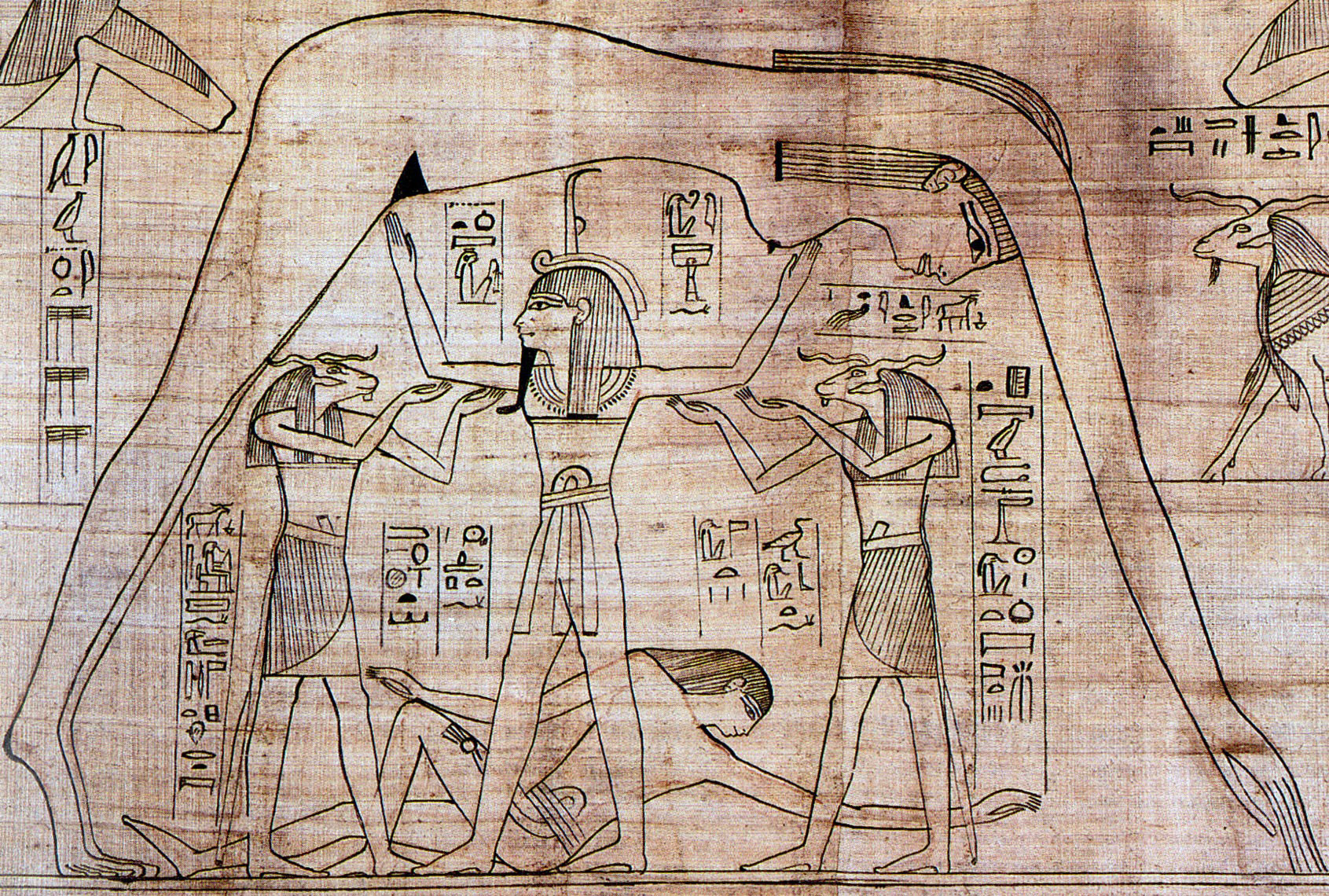

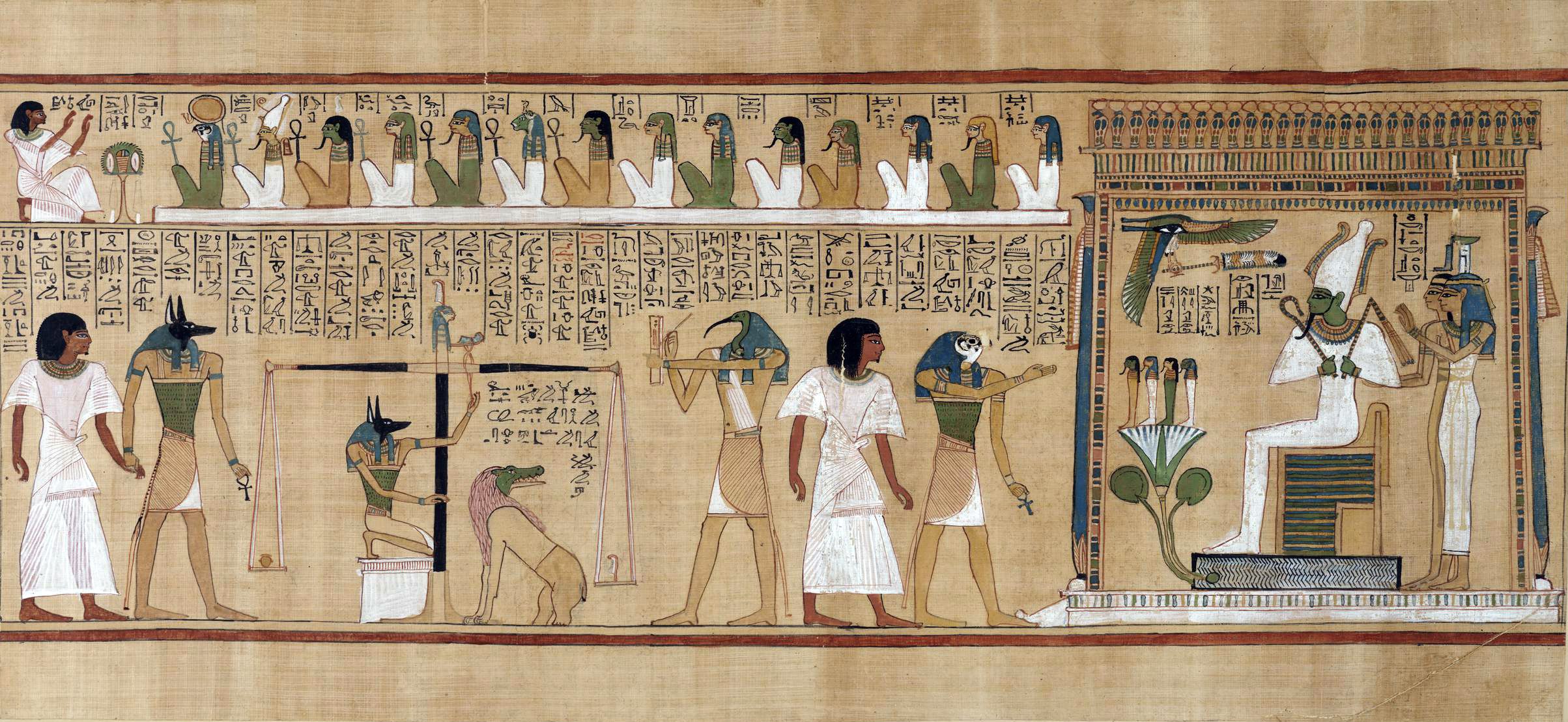

Page from the Book of the Dead of Ani, c. 1275 B.C.E., 19th Dynasty, 44.5 x 30.7 cm, Thebes, Egypt © Trustees of the British Museum

Eventually, the deceased reached the last judgment. This vitally important moment decided their fate. As they stood before the enthroned Lord of the Dead, Osiris, their heart was weighed on a scale against the feather of ma’at. Usually, a small image of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and cosmic balance, stood atop the scales to confirm the correctness of the weighing. The jackal-headed funerary god Anubis oversaw the weighing of the heart while the ibis-headed Thoth recorded the verdict. If their heart was “light as a feather,” the blessed dead were permitted to enter the idealized afterlife known as the Field of Reeds. For the unfortunate Egyptian whose heart was heavier than the feather of truth, a horrific monster with the head of a crocodile, body of a lion, and hindquarters of a hippopotamus—known as Ammit—waited eagerly to devour their heart and damn them to eternal oblivion. Obviously, in scenes of this judgment, the Egyptians always portrayed the scales balancing or with the heart even slightly lighter than the feather.

Learn about the journey of the deceased

Hunefer’s Judgement in the presence of Osiris: Look at one stunning example of this important scene.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Religion was woven into every aspect of life for the ancient Egyptian, whether king or commoner. The complex web created by the layers of rituals and stories that developed over the millenia provided the flexible structure that functioned as the psychological core for this enigmatic culture. Striving for the cosmic balance of ma’at in their daily lives, Egyptian society achieved largely-stable longevity and enjoyed great peaks that would suggest that they were doing at least something right.

Key questions to guide your reading

What does the art and architecture of ancient Egypt reveal about religious life and beliefs?

What do mortuary practices reveal about ancient Egyptian culture?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat does the art and architecture of ancient Egypt reveal about religious life and beliefs?

What do mortuary practices reveal about ancient Egyptian culture?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Coffin Texts

deity

ma'at

mastaba

mummification

polytheism

Pyramid Texts

votive