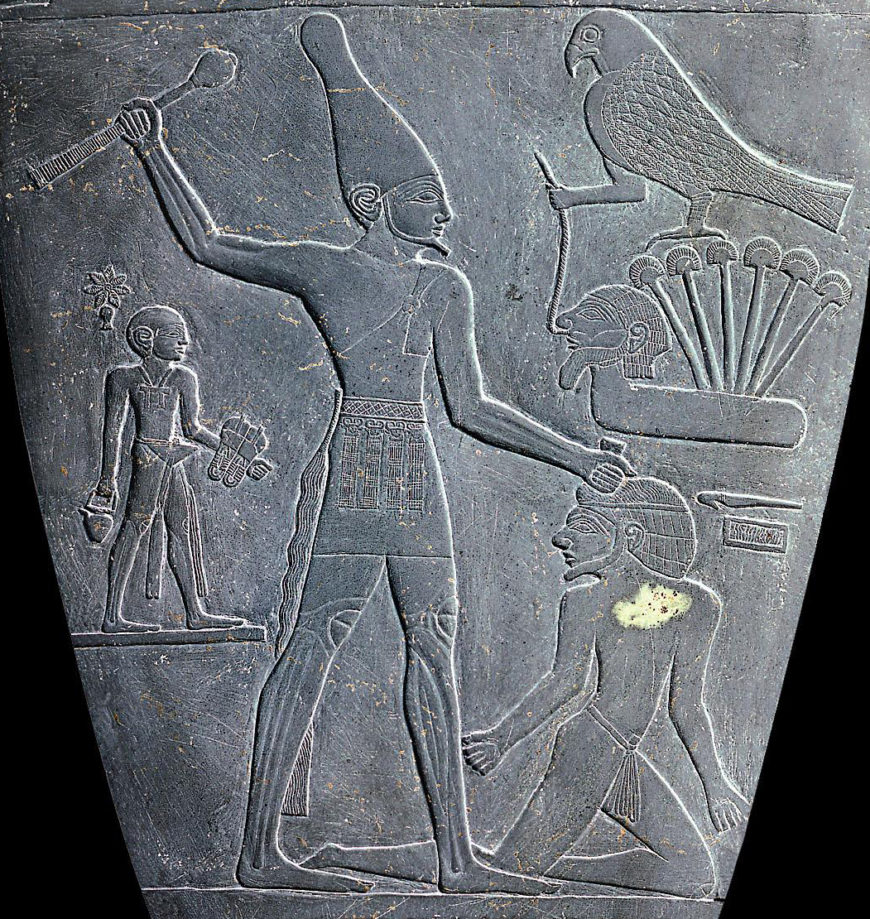

Palette of King Narmer, from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., slate, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

Vitally important, but difficult to interpret

Some artifacts are of such vital importance to our understanding of ancient cultures that they are truly unique and utterly irreplaceable. The gold mask of Tutankhamun was allowed to leave Egypt for display overseas; the Narmer Palette, on the other hand, is so valuable that it has never been permitted to leave the country.

Discovered among a group of sacred implements ritually buried in a deposit within an early temple of the falcon god Horus at the site of Hierakonpolis (a capital of Egypt during the Predynastic period), this large ceremonial object is one of the most important artifacts from the dawn of Egyptian civilization. The beautifully carved palette, 63.5 cm (more than 2 feet) in height and made of smooth greyish-green siltstone, is decorated on both faces with detailed low relief. These scenes show a king, identified by name as Narmer, and a series of ambiguous scenes that have been difficult to interpret and have resulted in a number of theories regarding their meaning.

The high quality of the workmanship, its original function as a ritual item dedicated to a god, and the complexity of the imagery clearly indicate that this was a significant object, but a satisfactory interpretation of the scenes has been elusive.

What was the palette used for?

The object itself is a monumental version of a type of daily use item commonly found in the Predynastic period—palettes were generally flat, minimally decorated stone objects used for grinding and mixing minerals for cosmetics. Dark eyeliner was an essential aspect of life in the sun-drenched region; like the dark streaks placed under the eyes of modern athletes, black cosmetic lines around the eyes served to reduce glare. Basic cosmetic palettes were among the typical grave goods found during this early era.

In addition to these simple, purely functional, palettes however, there were also a number of larger, far more elaborate palettes created in this period. These objects still served the function of being a ground for grinding and mixing cosmetics, but they were also carefully carved with relief sculpture. Many of the earlier palettes display animals—some real, some fantastic—while later examples, like the Narmer Palette, focus on human actions. Research suggests that these decorated palettes were used in temple ceremonies, perhaps to grind or mix makeup to be ritually applied to the image of the god. Later temple rituals included elaborate daily ceremonies involving the anointing and dressing of divine images; these palettes likely indicate an early incarnation of this process.

A ceremonial object, ritually buried

The Narmer Palette was discovered in 1898 by James Quibell and Frederick Green. It was found with a collection of other objects that had been used for ceremonial purposes and then ritually buried within the temple at Hierakonpolis.

Temple caches of this type are not uncommon. There was a great deal of focus on ritual and votive objects (offerings to the gods) in temples. Every ruler, elite individual, and anyone else who could afford it donated items to the temple to show their piety and increase their connection to the deity. After a period of time, the temple would be full of these objects and space needed to be made for new votive donations. However, since they had been dedicated to a temple and sanctified, the old items that needed to be cleared out could not simply be thrown away or sold. Instead, the general practice was to bury them in a pit dug under the temple floor. Often, these caches include objects from a range of dates and a mix of types, from royal statuary to furniture.

The “Main Deposit” at Hierakonpolis, where the Narmer Palette was discovered, contained many hundreds of objects, including a number of large relief-covered ceremonial mace-heads, ivory statuettes, carved knife handles, figurines of scorpions and other animals, stone vessels, and a second elaborately decorated palette (now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford) known as the Two Dogs Palette.

Conventions that remain the same for thousands of years

There are several reasons the Narmer Palette is considered to be of such importance. First, it is one of very few such palettes discovered in a controlled excavation, which means that we know it is authentic. Second, there are a number of formal and iconographic characteristics appearing on the Narmer Palette that remain conventional in Egyptian two-dimensional art for the following three millennia. These include the way the figures are represented, the scenes being organized in regular horizontal zones known as registers, and the use of hierarchical scale to indicate relative importance of the individuals. In addition, much of the regalia worn by the king, such as the crowns, kilts, royal beard, and bull tail, as well as other visual elements, including the pose Narmer takes on one of the faces where he grasps an enemy by the hair and prepares to smash his skull with a mace, continue to be utilized from this time all the way through the Roman era more than 3000 years later.

What we see on the palette

The king is represented twice in human form, once on each face, followed by his sandal-bearer. He may also be represented as a powerful bull, destroying a walled city with his massive horns, in a mode that again becomes conventional—pharaoh is regularly referred to as “Strong Bull” in later texts.

In addition to the primary scenes, the palette includes a pair of fantastic creatures, known as serpopards—leopards with long, snaky necks—who are collared and controlled by a pair of attendants. Their necks entwine and define the recess where the makeup preparation took place. The lowest register on both sides include images of dead foes, while both uppermost registers display hybrid human-bull heads and the name of the king. The frontal bull heads are connected to a sky goddess known as Bat and are related to heaven and the horizon. The name of the king, written hieroglyphically as a catfish and a chisel, is contained within a squared element that represents a palace facade.

Possible interpretation: unification of Upper and Lower Egypt

As mentioned above, there have been a number of theories related to the scenes carved on this palette. Some have interpreted the battle scenes as a historical narrative record of the initial unification of Egypt under one ruler, supported by the general timing (as this is the period of the unification) and the fact that Narmer sports the crown connected to Upper Egypt on one face of the palette and the crown of Lower Egypt on the other—this is the first preserved example where both crowns are used by the same ruler. Other theories suggest that, rather than an actual historical representation, these scenes were purely ceremonial and related to the concept of unification in general.

Detail, Palette of King Narmer, from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., slate, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

Another interpretation: the sun and the king

More recent research on the decorative program has connected the imagery to the careful balance of order and chaos (known as ma’at and isfet) that was a fundamental element of the Egyptian idea of the cosmos. It may also be related to the daily journey of the sun god that became a central aspect in the Egyptian religion in the subsequent centuries.

Detail, Palette of King Narmer, from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., slate, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

The scene showing Narmer wearing the Lower Egyptian Red Crown* (with its distinctive curl) depicts him processing towards the decapitated bodies of his foes. The two rows of prone bodies are placed below an image of a high-prowed boat preparing to pass through an open gate. This may be an early reference to the journey of the sun god in his boat. In later texts, the Red Crown is connected with bloody battles fought by the sun god just before the rosy-fingered dawn on his daily journey and this scene may well be related to this. It is interesting to note that the foes are shown as not only executed, but rendered completely impotent—their castrated penises have been placed atop their severed heads.

On the other face, Narmer wears the Upper Egyptian White Crown* (which looks rather like a bowling pin) as he grasps an inert foe by the hair and prepares to crush his skull with a mace. The White Crown is related to the dazzling brilliance of the full midday sun at its zenith as well as the luminous nocturnal light of the stars and moon. By wearing both crowns, Narmer may not only be ceremonially expressing his dominance over the unified Egypt, but also the early importance of the solar cycle and the king’s role in this daily process.

This fascinating object is an incredible example of early Egyptian art. The imagery preserved on this palette provides a peek ahead to the richness of both the visual aspects and religious concepts that develop in the ensuing periods. It is a vitally important artifact of extreme significance for our understanding of the development of Egyptian culture on multiple levels.

*The Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt were the earliest crowns worn by the king and are closely connected with the unification of the country that sparks full-blown Egyptian civilization. The earliest representation of them being worn by the same ruler is on the Narmer Palette, signifying that the king was ruling over both areas of the country. Soon after the unification, the fifth ruler of the First Dynasty is shown wearing the two crowns simultaneously, combined into one. This crown, often referred to as the Double Crown, remains a primary crown worn by pharaoh throughout Egyptian history. The separate Red and White crowns, however, continue to be worn as well and retain their geographic connections. There are a number of Egyptian words used for these crowns (nine for the White and 11 for the Red), but the most common—deshret and hedjet—refer to the colors red and white, respectively. It is from these identifying terms that we take their modern name. Early texts make it clear that these crowns were believed to be imbued with divine power and were personified as goddesses.