Did Hunefer live an ethical life? See the judgment of the Egyptian gods—who weigh Hunefer’s heart.

Hunefer’s Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead of Hunefer, c. 1275 B.C.E. (19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, Thebes, Egypt), papyrus (The British Museum). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Erratum: near the end of the video we say that Nephthys and Anubis are siblings; this is not correct.

Hunefer: an ancient Egyptian official

Hunefer and his wife Nasha lived during the Nineteenth Dynasty, in around 1310 B.C.E. He was a “Royal Scribe” and “Scribe of Divine Offerings.” He was also “Overseer of Royal Cattle,” and the steward of King Sety I. These titles indicate that he held prominent administrative offices and would have been close to the king. The location of his tomb is not known, but he may have been buried at Memphis.

Hunefer’s high status is reflected in the fine quality of his Book of the Dead, which was specially produced for him. This, and a Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure, inside which the papyrus was found, are the only objects which can be ascribed to Hunefer. The papyrus of Hunefer is characterized by its good state of preservation and the large, and clear vignettes (illustrations) are beautifully drawn and painted. The vignette illustrating the “Opening of the Mouth” ritual is one of the most famous pieces of papyrus in The British Museum collection, and gives a great deal of information about this part of the funeral.

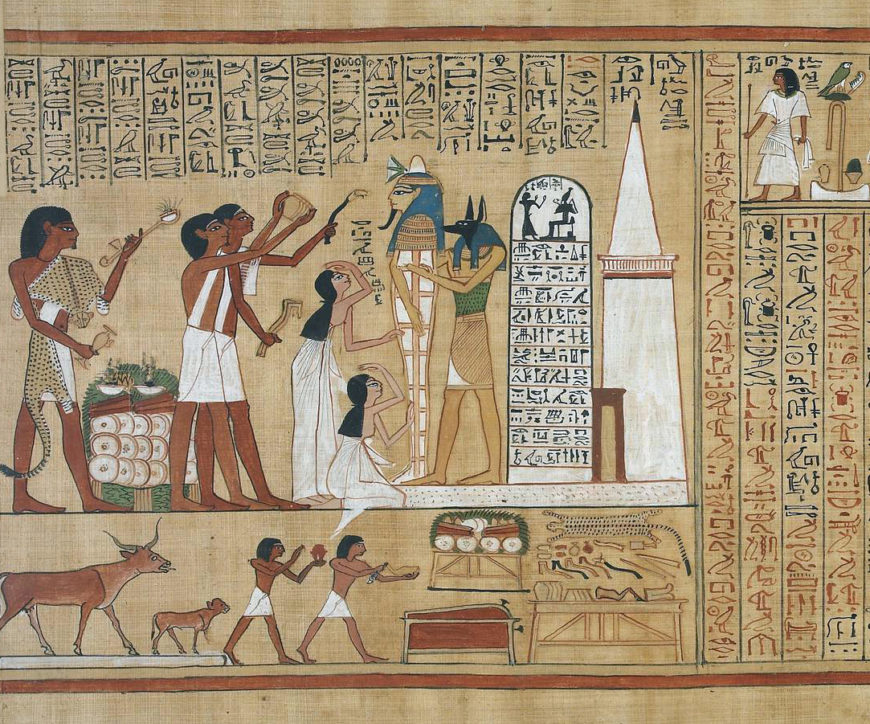

Page from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, c. 1275 B.C.E. (Thebes, Egypt), 45.7 x 83.4 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Pages from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer

The centerpiece of the upper scene is the mummy of Hunefer, shown supported by the god Anubis (or a priest wearing a jackal mask). Hunefer’s wife and daughter mourn, and three priests perform rituals. The two priests with white sashes are carrying out the Opening of the Mouth ritual. The white building at the right is a representation of the tomb, complete with portal doorway and small pyramid. Both these features can be seen in real tombs of this date from Thebes. To the left of the tomb is a picture of the stela which would have stood to one side of the tomb entrance. Following the normal conventions of Egyptian art, it is shown much larger than normal size, in order that its content (the deceased worshipping Osiris, together with a standard offering formula) is absolutely legible.

At the right of the lower scene is a table bearing the various implements needed for the Opening of the Mouth ritual. At the left is shown a ritual, where the foreleg of a calf, cut off while the animal is alive, is offered. The animal was then sacrificed. The calf is shown together with its mother, who might be interpreted as showing signs of distress.

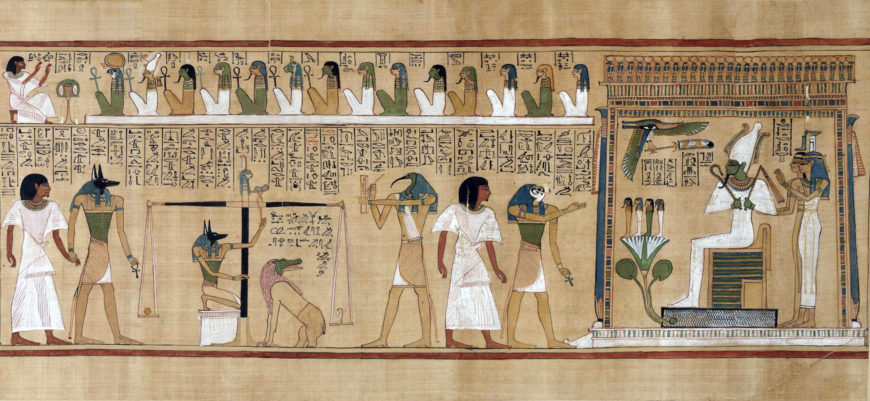

Page from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, c. 1275 B.C.E. (19th Dynasty, Thebes, Egypt), 40 x 87.5 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The scene reads from left to right. To the left, Anubis brings Hunefer into the judgement area. Anubis is also shown supervising the judgement scales. Hunefer’s heart, represented as a pot, is being weighed against a feather, the symbol of Maat, the established order of things, in this context meaning ‘what is right’. The ancient Egyptians believed that the heart was the seat of the emotions, the intellect and the character, and thus represented the good or bad aspects of a person’s life. If the heart did not balance with the feather, then the dead person was condemned to non-existence, and consumption by the ferocious “devourer,” the strange beast shown here which is part-crocodile, part-lion, and part-hippopotamus.

However, as a papyrus devoted to ensuring Hunefer’s continued existence in the Afterlife is not likely to depict this outcome, he is shown to the right, brought into the presence of Osiris by his son Horus, having become “true of voice” or “justified.” This was a standard epithet applied to dead individuals in their texts. Osiris is shown seated under a canopy, with his sisters Isis and Nephthys. At the top, Hunefer is shown adoring a row of deities who supervise the judgement.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources

This work at The British Museum

What is a Book of the Dead? from The British Museum

R.O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead (revised edition C. A. R. Andrews) (London: The British Museum Press, 1985).

R.B. Parkinson and S. Quirke, Papyrus (Egyptian Bookshelf) (London: The British Museum Press, 1995).

S. Quirke and A.J. Spencer, The British Museum book of ancient Egypt (London: The British Museum Press, 1992).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”hunefer,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the British Museum in London, in a room that is filled with ancient Egyptian mummies. As a result, it’s also filled with modern children.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:15] And tourists. It’s a great room, there’s great stuff here.

Dr. Zucker: [0:18] We’re looking at a fragment of a scroll, which is largely ignored.

Dr. Harris: [0:22] It’s a papyrus scroll.

Dr. Zucker: [0:24] Papyrus is a reed that grows in the Nile Delta that was made into a kind of paper-like substance, and actually was probably the single most important surface for writing right up into the medieval.

Dr. Harris: [0:35] We’re looking at a written text of something that we call “The Book of the Dead,” which the ancient Egyptians had other names for, but which was an ancient text that had spells and prayers and incantations. Things that the dead needed in the afterlife.

Dr. Zucker: [0:50] This is a tradition that goes all the way back to the Old Kingdom, writing that we call “pyramid text.” These were sets of instructions for the afterlife, and then later we have coffin text, writing on coffins. Then even later in the New Kingdom, we have scrolls like this that we call the “Books of the Dead.”

Dr. Harris: [1:08] Sometimes the texts were written on papyrus, like the one we’re looking at. Sometimes they were written on shrouds that the dead were buried in. These were really important texts that were originally just for kings in the Old Kingdom, but came to be used by people who were not just part of the royal family but still people of high rank, and that’s what we’re looking at here.

[1:30] This text was found in the tomb of someone named Hunefer, a scribe.

Dr. Zucker: [1:35] A scribe had a priestly status, so we are dealing here with somebody who was literate, who occupied a very high station in Egyptian culture. We actually see representations of the man who had died, who was buried with this text. If you look on the left edge of this scroll, at the top, you can see a crouching figure in white.

[1:55] Hunefer, who is speaking to a line of crouching deities, gods, professing the good life that he lived, that he has earned a place in the afterlife.

Dr. Harris: [2:04] Well, what we have below is a scene of judgment. Whether Hunefer has lived a good life and deserves to live into the afterlife. We see Hunefer, again, this time standing on the far left.

Dr. Zucker: [2:17] We can recognize him because he’s wearing the same white robe.

Dr. Harris: [2:21] He’s being led by the hand by a god with a jackal head, Anubis, a god that’s associated with the dead, with mummification, with cemeteries. He’s carrying in his left hand an ankh.

Dr. Zucker: [2:34] A symbol of eternal life, and that’s exactly what Hunefer is after.

Dr. Harris: [2:38] If we continue to move toward the right, we see that jackal-headed god again, Anubis, this time crouching and adjusting the scale.

Dr. Zucker: [2:46] Making sure that it is exactly balanced. On the left side, we see the heart of the dead.

Dr. Harris: [2:52] The heart is on one side of the scale, on the other side is a feather. The feather belongs to Ma’at, who we also see at the very top of the scale. We can see a feather coming out of her head. Now, Ma’at is a deity associated with divine order, with living an ethical, ordered life.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] In this case the feather is lower, the feather is heavier. Hunefer has lived an ethical life and therefore is brought into the afterlife.

Dr. Harris: [3:21] He won’t be devoured by that evil-looking beast next to Anubis. That’s Ammit, who has the head of a crocodile, the body of a lion, and the hindquarters of a hippopotamus. He’s waiting to devour Hunefer’s heart, should he be found to have not lived an ethical life, not lived according to Ma’at.

Dr. Zucker: [3:42] The Egyptians believed that only if you lived the ethical life, only if you pass this test, would you be able to have access to the afterlife. It’s not like the Christian conception, where you have an afterlife for everybody no matter if they’re blessed or sinful.

[3:56] That is, you either go to heaven or you go to hell. Here, you only go to the afterlife if you have been found to be ethical.

Dr. Harris: [4:04] The next figure that we see is another deity, this time with the head of an ibis, of a bird. This is Thoth, who is recording the proceedings of what happens to Hunefer. In this case, recording that he has succeeded and will move on to the afterlife.

Dr. Zucker: [4:21] I love the representation of Thoth. He is so upright and his arm is stretched out, rendered in such a way that we trust him. He’s going to get this right.

Dr. Harris: [4:30] Next, we see Hunefer yet again. This time being introduced to one of the supreme gods in the Egyptian pantheon, Osiris. He’s being introduced to Osiris by Osiris’s son, Horus.

Dr. Zucker: [4:44] Horus is easy to remember because Horus is associated with the falcon and here has a falcon’s head. Horus is the son of Osiris and holds in his left hand an ankh, which we saw earlier.

[4:56] Again, that’s a symbol of eternal life. He is introducing him to Osiris as you said, who is in this fabulous enclosure, speaks to the importance of this deity.

Dr. Harris: [5:05] He’s enthroned, he carries symbols of Egypt, and he sits behind a lotus blossom, a symbol of eternal life. On top of that lotus blossom, Horus’s four children who represent the four cardinal points, north, south, east, and west.

Dr. Zucker: [5:23] The children of Horus are responsible for caring for the internal organs that would be placed in canopic jars, so they have a critical responsibility for keeping the dead preserved.

Dr. Harris: [5:33] We see Horus again, but symbolized as an eye. Now remember, Horus is represented as a falcon, as a bird, so here even though he’s the symbol of the eye, he has talons instead of hands, and those carry an ostrich feather, also a symbol of eternal life.

Dr. Zucker: [5:49] The representation of the eye of Horus has to do with another ancient Egyptian myth, the battle between Horus and Seth, but that’s another story.

Dr. Harris: [5:56] Now behind Osiris we see two smaller standing female figures, one of whom is Isis, Osiris’s wife. The other is her sister, Nephthys, who’s a guardian of the afterlife and sister of Anubis, the figure who we saw in the very beginning leading Hunefer into judgment.

Dr. Zucker: [6:14] Notice the white platform that those figures are standing on—that represents natron, the natural salts that are deposited in the Nile, and that were used by the ancient Egyptians to dry out all of the mummies that are in this room so that they could be preserved.

Dr. Harris: [6:29] Actually the word “preservation” is really key to thinking about Egyptian culture generally because this is a culture whose forms, whose representations in art, remain remarkably the same for thousands of years, even though there are periods of instability. Or even just before this we had the Amarna period, where we saw very different way of representing the human figure.

[6:50] What we see here, these forms look very familiar to us because this is the typical way the ancient Egyptians represented the human figure.

Dr. Zucker: [7:00] Even though this is a painting from the New Kingdom, these forms would have been recognizable to Egyptians thousands of years earlier in the Old Kingdom.

Dr. Harris: [7:09] We see that mixture that we see very often in ancient Egyptian art, of words, of hieroglyphs, of writing and images.

Dr. Zucker: [7:16] Love the mix. In our modern culture we really make a distinction between written language and the visual arts, and here in ancient Egypt it really is this closer relationship, this greater sense of integration.

[7:27] [music]