Mummy of Herakleides, 120–140 C.E., Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains; linen, pigment, beeswax, gold, and wood, 175.3 x 44 x 33 cm (Getty Villa, Los Angeles; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Little evokes ancient Egypt more quickly for more people than mummies. Over the millennia, scores of them have been unearthed and these complex echoes from the past have been handled in very different ways during that time. Often viewed more as artifacts and curios rather than as human remains, they were ground to powder for use in medicinal concoctions for many centuries (and, later, oil paints!), sometimes burned unceremoniously as fuel, and unwrapped with great fanfare at fashionable parties in the Victorian era. Today, mummies are treated with far greater respect and have provided deep insights and a vast amount of information about these ancient people, but their display and presentation remains a controversial topic.

The earliest burials known from Egypt were simple pits scooped out of the desert sand. These contained the bodies of the deceased, usually curled on their side in a fetal position, and often included objects of daily life such as pots, beads, tools, and other small items. Dated prior to the time of unification (well before 3000 B.C.E.), early cemeteries were located along the edge of the desert near settlements, the desert west of the Nile was already considered the land of the dead. Over time, the continued existence of the body on earth came to be viewed as essential for a successful afterlife. The physical corpse (or an inscribed image, or even one’s written name) served as a conduit with earth that allowed sustenance from offerings and magical spells included in the tomb or inscribed on its walls to flow to the deceased in the netherworld. Given the importance placed on the body, it is not surprising that the art of mummification developed to such an exceptional degree. There was a huge range of experimentation that occurred over Egypt’s long history of mummification, some techniques being far more successful than others.

Mummification

Sadly, no step-by-step guide to mummification has yet been discovered. Some 3rd–1st century B.C.E. papyri record wrapping instructions, amulet placement, and some spells, but the most detailed textual description of the process comes from the 5th-century B.C.E. Greek historian Herodotus in Book II of his Histories. He describes three different types of embalming, varying in expense, complexity, and quality of result.

Canopic Jar with a Lid in the Shape of a Royal Woman’s Head, c. 1352–1336 B.C.E., reign of Akhenaten, Dynasty 18, New Kingdom, Amarna Period Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Valley of the Kings, Tomb KV 55, Davis/Ayrton 1907 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In its full-fledged incarnation, the high-quality process of mummification took around 70 days and entailed:

-

Death Mask from innermost coffin, Tutankhamun’s tomb, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1323 B.C.E., gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones (Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo: Mark Fischer, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Removing the viscera (liver, lungs, intestines, and stomach) through an incision in the left side; these organs were mummified separately and placed in four canopic jars. The heart, considered the seat of intelligence, was usually left inside the body.

- The mysterious brain, a wet organ that encouraged putrification (which was anathema to the mummification process), was removed through the nostrils using a long metal hook and discarded.

- The body was washed with palm wine, dried, and then covered with natron (netjry, in ancient Egyptian, which translates to “divine salt”). This powdery salt, derived from an oasis near the delta called the Wadi Natrun, desiccated the body over a period of up to 40 days.

- Once dried out, the body was uncovered, ritually cleaned, and then anointed with fragrant oils and a thick coating of resin.

- Then the body was wrapped with many layers of linen strips—a process that could take more than two weeks. Between the layers, various amulets were placed in specific locations with the hopes that they would aid the deceased in their netherworld journey. In royal burials, precious jewelry and regalia were included in these layers; the intact mummy of Tutankhamun included more than 150 objects wrapped in his linen. When the wrapping was complete, the bandages were thoroughly soaked with liquified resin.

- To maintain the identity of the body, a mask could be placed on the mummy’s head. In later periods, a portrait was painted on a wood panel and inserted into the bandages. The mummy was then encased in a coffin, usually covered with amuletic scenes and texts that identified the deceased and provided them with the magical spells needed to safely traverse the dangerous netherworld.

Mummy with a portrait of Herakleides, 120–140 C.E., Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains, linen, pigment, beeswax, and wood (The Getty Villa; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The mid-range method omitted steps, such as the incision and manual removal of the viscera, while the least expensive option entailed the body simply be washed, dried in natron, and then wrapped.

Mask likely to be worn by a male priest playing the part of Anubis in a temple during mummification or burial ritual. Probably buried with the priest who had worn it in life. Anubis mask, 8–4 B.C.E., cartonnage, coarse linen, mud plaster mixed with straw, probably excavated in Thebes, Egypt, 24 x 36 cm (Harrogate Museums and Arts)

Archeological evidence has provided a great deal of additional information about this complex process beyond what was written in antiquity. For instance, although there are no texts referring to the practice, numerous discoveries of caches of carefully buried used embalming materials have given valuable insight into the techniques used. Not much is known about the ancient embalmers, except that wrapping was typically performed by a special class of priests, one of whom seems to have been masked and performed as the god Anubis.

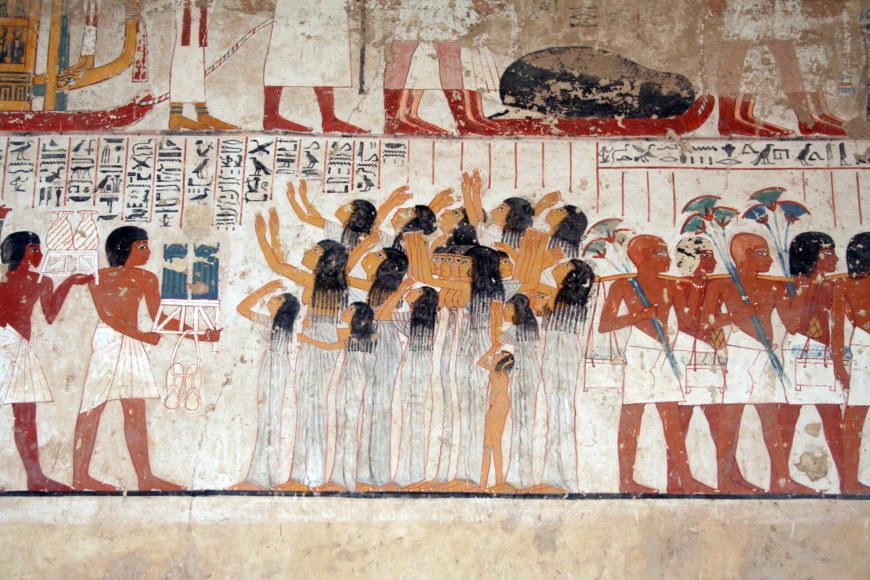

Mourners in the funerary procession of Ramose, Tomb of the Vizier Ramose (TT 55), Western Thebes, Dynasty 18. Note the white sandals and other grave goods being carried by figures around the mourners (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Funerary rites

Once the mummy was prepared, it was retrieved from the embalmers by the family. The mummy was placed in its prepared coffin and taken in procession to the tomb along with all the items destined to join the deceased in the afterlife. Included in this mournful group would be friends and family, along with priests to perform the funerary rituals and (if the deceased was wealthy) professional mourners who wailed and tore their clothing in anguish. Expressive tomb paintings of funerary processions show these figures with disheveled hair and tears streaming down their faces as they accompany the deceased on their final terrestrial journey.

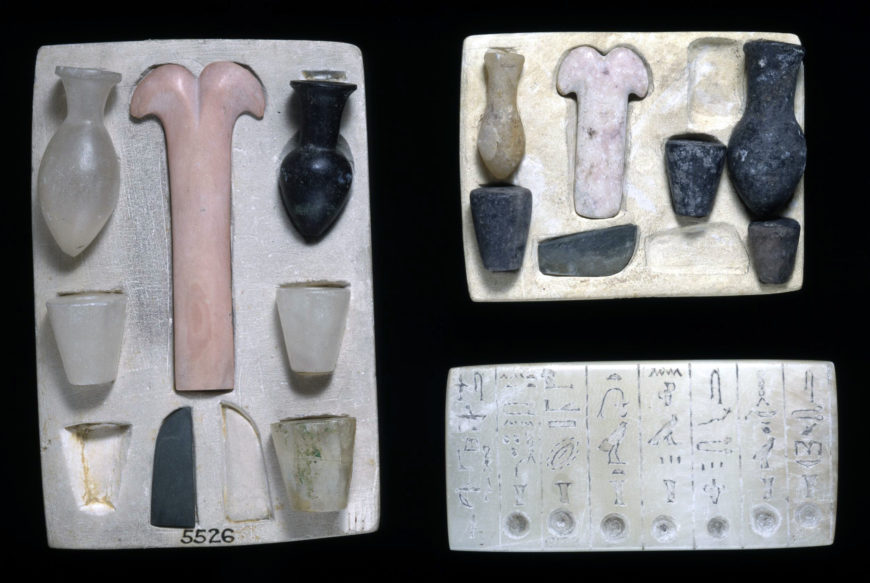

Model of equipment for Opening of Mouth Ceremony: five vessels (calcite and limestone), a small knife blade and a pesesh-kef implement (schist and limestone) set into depressions of limestone tablet, 6th dynasty, Egypt (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The last stage before burial was a special ceremony performed by the heir and a priest wearing a panther skin wrapped around their torso. This “Opening of the Mouth” ritual was considered essential as it allowed the deceased to fully engage in the afterlife. The ceremony involved touching the organs related to the senses—eyes, ears, nose, and mouth—with special instruments, such as an adze (a woodworking tool) and a double-forked knife called a pesesh-kef. It is fascinating to note that these instruments were related to those used during childbirth, like the pesesh-kef that was also used to cut the umbilical cord. These ritual actions allowed the mummy’s senses to become magically useful again and permitted the deceased to be a fully functional being and an effective akh in the afterlife.

Once all the necessary rites had been completed, there was a funerary feast held in front of the tomb with the mummy, often draped in flower garlands, as guest of honor. Then, the mummy—along with its offerings and grave goods—was placed into the burial chamber and sealed away. This final act initiated the deceased’s passage into the netherworld, providing spells, guides, protective amulets, and tools in their tombs to aid them along that dangerous journey. Their eventual goal was to reach the idealized Field of Reeds (the Egyptian version of heaven) and enjoy an eternity in that place of perfection, sustained for all time through their terrestrial link to the tomb reliefs, grave goods, and ongoing offerings provided.

Although the living went back to their lives when they left the funeral, the deceased was far from forgotten. Regular festival occasions included visits to the tomb by family, sometimes with memorial picnics taking place in the area before the chapel, and gifts and offerings were left. Once a deceased Egyptian was perceived to have successfully navigated the dangerous pathways of the netherworld and achieved their place in the Field of Reeds, their living relatives and descendants would sometimes approach with petitions or requests for guidance. Often referred to as “Letters to the Dead,” these written requests for otherworldly intervention in the affairs of the living were usually written on small clay bowls filled with a food offering to entice the deceased spirit to help bring about the desired result.

For the ancient Egyptians, the dead were never truly forgotten. Even by speaking the name of an individual, the living helped guarantee eternal existence of that being in the afterlife.

Additional resources

A brief video outlining the mummification of a late Ptolemaic period man, including the layers of wrappings and how the portrait was inserted.