Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Pyramid building in ancient Egypt had its “big bang” at Saqqara in the 3rd Dynasty with a genius named Imhotep, who served as chancellor to king Netjeryknet, better known as Djoser. Djoser not only placed his mortuary complex (which was intended for the king’s ka (spirit) to use in the afterlife) at the site of Saqqara—a different location from his predecessors—but the complex he developed with Imhotep would impact all royal memorial monuments made after his. While the complex had many innovations, among the most important are that it was the first mortuary structure in stone, the first stepped pyramid instead of a single mastaba (a flat, rectangular tomb form), and the first to combine both mortuary and ritual buildings, and to pair functional buildings with dummy ones that couldn’t actually be used.

Djoser’s complex has numerous features, and this essay introduces some of the most important ones as it walks readers through the site. They include the:

- enclosure wall and entrance to the complex

- entry colonnade

- south court

- T-temple

- Heb Sed Court

- North and South Houses

- Step Pyramid

- Serdab and temple to the ka

- King’s burial chamber

- subterranean chambers

- South Tomb

Royal enclosure of King Khasekhemwy (known as the Shunet el Zebib), end 2nd Dynasty c. 2650 B.C.E., Abydos, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The move to Saqqara

Djoser’s royal predecessors had created large memorial complexes at the ancient site of Abydos, further to the south. These consisted of a huge, rectangular mud brick enclosure with towering walls decorated with an elaborate pattern of rectangular recesses and a subterranean tomb about 3.2 km to the southwest, towards an opening in the high desert cliffs that was believed to be the entrance to the Netherworld.

Left: Walls of the enclosure of King Khasekhemwy showing niched pattern; right: Early Dynastic royal tombs at Abydos with opening in the cliffs in background, Abydos, Egypt (photos: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Djoser chose instead to place his mortuary complex at the site of Saqqara, where the burials of some earlier local rulers and elite already existed. These earlier burials at Saqqara included elaborate niched facades and subterranean chambers that may have served as models or inspiration. However, the architectural importance of Djoser’s complex cannot be overstated—there were multiple innovations that had a significant impact on all royal memorial monuments that followed.

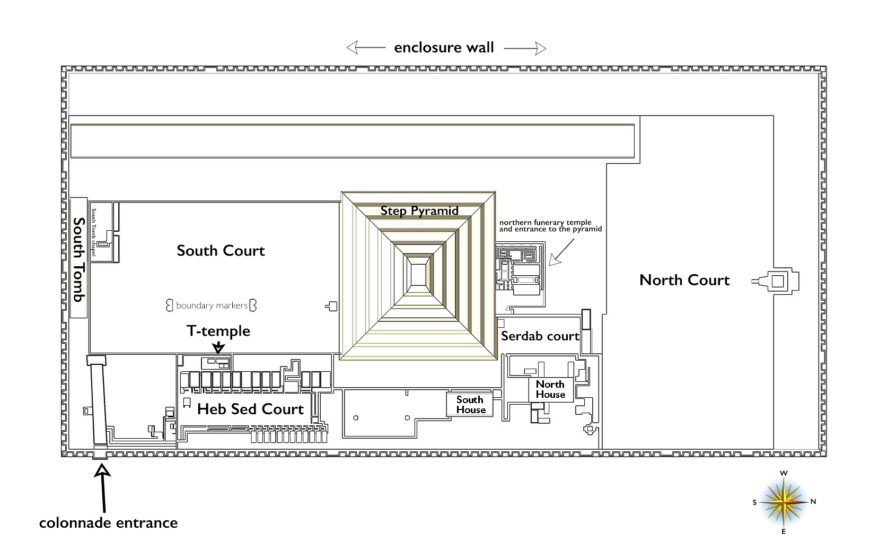

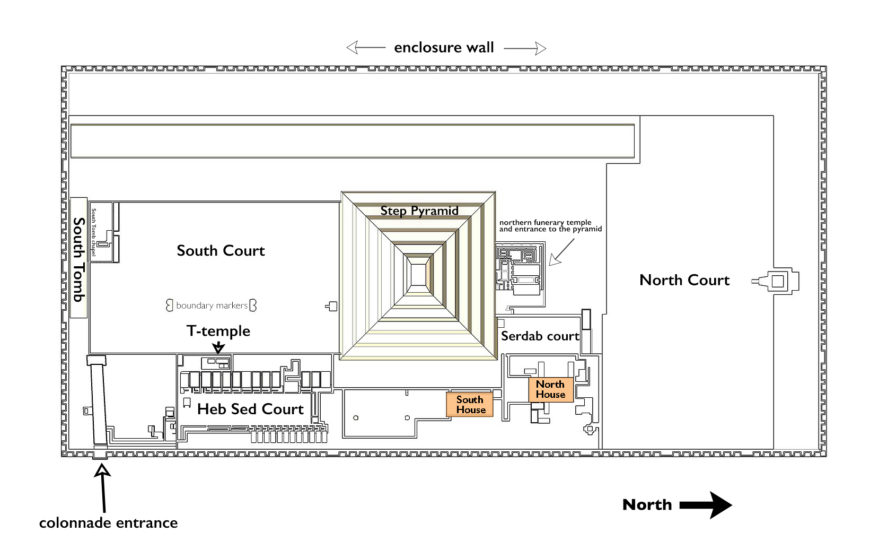

Plan of Djoser’s Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (plan: Franck Monnier, CC BY-SA 3.0)

For Djoser’s complex, a rectangular section of desert was delineated by boundary stela, a massive trench, and a wall containing an area of 37 acres. Inside this substantial enclosure was a series of structures, courtyards, underground tunnels, and chapels in addition to the stepped pyramid that visually dominates the space. Although built of stone, many of the forms and architectural elements within this complex—from the design of the enclosure walls to the shapes of the columns—were based on and often directly mimic structures built from perishable materials. The Step Pyramid complex is a striking example of the transitory made permanent on a massive scale because of the shift from mud brick and other perishable materials to stone.

There is evidence that some structures were partially buried almost immediately upon their completion. This type of ritual burial was also known from Abydos and perhaps signifies the hidden aspect of life after death where successive layers of each building concealed earlier ones and eventually led to the emergence of new life. The ideal cycle of eternal renewal in Ancient Egyptian conception required burial as part of the process. By burying these ritual structures, the Egyptians believed that they (and their associated rejuvenating rituals) became available for the use of the deceased king in the afterlife and remained conceptually accessible to him forever in that realm. At Djoser’s complex, the shift to building entirely with stone shows a desire to provide an even better guarantee of eternal availability.

General view from exterior showing the entrance, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Innovations

For the first time, the material used was not mud brick, but instead carefully cut stone. Domestic structures for the living and even palaces for the kings had been, and would continue to be, constructed of organic, more temporary materials like reeds, mudbrick, and wood; however, from this point on, royal memorial constructions (like temples and tombs) would be made of stone.

The combination of both mortuary and ritual structures in the same complex was another of Djoser and Imhotep’s innovations—previously at Abydos, the king’s tomb and the royal enclosures used for enacting rituals related to that ruler were physically separated by an expanse of open desert.

There is also a mix within the Step Pyramid enclosure of functional and “dummy” buildings. The functional structures were probably used in the conduct of actual rituals during the king’s lifetime and funerary rites after his death. “Dummy” buildings are as they sound—solid structures behind a façade—that were apparently intended for the ka’s use in the afterlife.

Djoser and his ground-breaking complex were honored thousands of years after his death. His chancellor and the architectural mastermind behind the complex, Imhotep (“He who comes in peace”), was also memorialized for the magnificent monument he designed for his ruler. Imhotep was highly respected for his wisdom and was later deified, which was very rare for non-royal individuals. Even thousands of years after his death, Imhotep was still revered. In the 3rd century B.C.E. a priest named Manetho wrote one of the earliest histories of Egypt. In it, he specifically credits Imhotep with the invention of building in stone. His reputation as a wise man and healer eventually led the Greeks to associate him with Asclepius, the god of medicine, and his worship continued.

Portion of enclosure wall (only partially reconstructed today) showing recesses, originally 10.5 meters tall and 1,645 meters in length, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Enclosure wall and entrance to the complex

The entire complex was surrounded by a massive wall, built of fine white limestone blocks (see the plan above). The monumental circuit was decorated with niches and recesses that mimic the façade of a palace, much like the earlier mudbrick enclosures from Abydos and elite tombs at Saqqara. A fascinating detail is that these 1,680 recessed rectangular panels were carved into the stone after the wall was constructed rather than being shaped as the blocks were laid. Though we are not sure of its significance, the elaborate niched pattern was considered essential and worth the immense amount of physical effort this must have required.

Entrance gate at the southeast corner, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

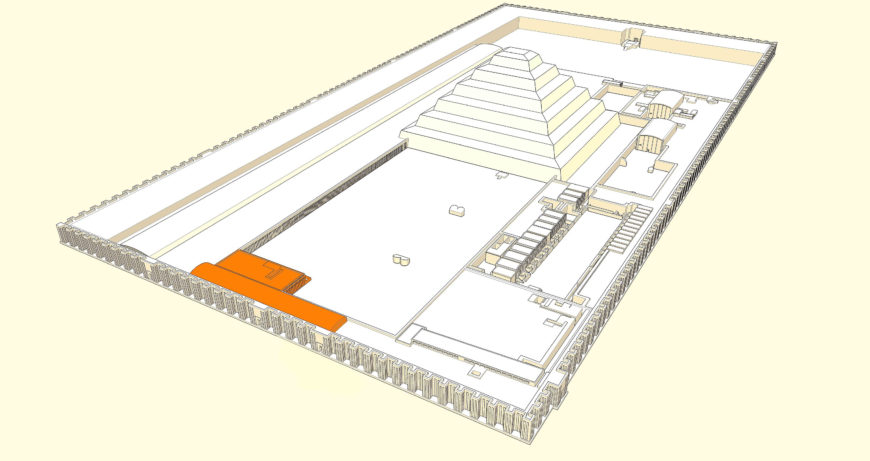

Entrance and the entry colonnade (in orange), Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (image: Franck MONNIER Bakha, CC BY-SA 1.0)

A series of dummy gates is carved into the enclosure wall at irregular intervals; just one gate includes an actual entrance. This single opening to the ritual enclosure—a passage only 1 meter wide and 5 meters long—enhances and highlights the privacy of this space, which was intended for the king’s ka (his spirit) to use in the afterlife. The entrance corridor leads to a small court that has representations of wooden doors carved in stone as if they were always open so that the king’s ka to come and go. There was almost certainly also a wooden door that actually could be closed and sealed when the complex was functioning.

Left: entry colonnade with columns 6 meters in height; right: stone log-beam ceiling in the colonnade, with columns that look like bundled reeds. Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (photos: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Entry Colonnade

The entrance corridor and small court lead to a second, slightly wider, passageway that opens into an elegant colonnaded court with two rows of twenty engaged columns flanking the walkway (see the plan above). These were carved to look like bundled reeds and may have been painted green. While in earlier phases of the complex this court was open to the sky, later it was closed in with a roof, carved of stone but shaped like log-beams and originally painted red in an imitation of wood, and a clerestory was added to bring light into the space.

The specific ritual purpose of this space is debated, but the unusual engagement of the columns—connected to the side walls by masonry projections—created deep niches that likely served a cultic function and may have originally held statuary. The end of this colonnade opens into a rectangular hall that includes four similar, if slightly shorter, attached columns. Again, the portal includes the representation of a wooden door rendered in stone with extreme detail and sensitivity.

Passageway through enclosure wall, only 1 m in width, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Given that the only actual entrance through the stone enclosure wall is a mere 1 meter wide and not near to the stepped pyramid (under which Djoser was buried), the funeral procession that occurred after Djoser’s death almost certainly entered via a temporary ramp that went over the wall at a point closer to the pyramid—evidence of such a ramp still exists.

View of the South Court (approximately 180 meters x 100 meters) after leaving the entrance colonnade, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

South Court

Emerging from the entrance colonnade, one enters a huge open space that is bordered by the Step Pyramid and by the enclosure wall and a mysterious cenotaph known as the South Tomb (see the plan above). Within the open courtyard are a pair of large stones, shaped like a double-horseshoe and approximately 45 meters apart. These distinctive markers were used as part of the king’s renewal rituals during the important heb-sed festival. This festival was typically celebrated in Year 30 of a king’s reign and, during Djoer’s lifetime, he may have performed it here. During the festival, there was a special ritual “race” he had to run around these markers, which represented the edges of the realm, to demonstrate his athletic nature and continued ability to rule.

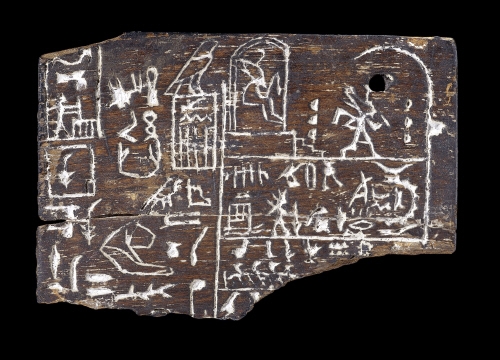

Label with a scene showing the jubilee of King Den, 1st Dynasty, c. 2950 B.C.E., ebony, from the Tomb of King Den, Abydos, Egypt (©Trustees of the British Museum)

Earlier representations, such as on an ebony label of king Den discovered in his tomb at Abydos, show the king racing around a set of similar stones that represented the extent of the ruler’s territory. This important ritual is also replicated in stone, delicately-carved in 3 of the 6 relief panels that were found in the Subterranean Chambers below the Step Pyramid and in the South Tomb (read more on this below).

Left: Temple T (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert); right: plan of the Stepped Pyramid complex, with Temple T (the King’s Pavilion) indicated in orange (Monnier Franck, CC BY 2.5)

The T-Temple

Engaged columns on the T-Temple, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Denitsa Takeva-Germanova)

Between the Entry Colonnade and courts there is a small structure which is often referred to as the “King’s Pavilion” (also called ‘Temple T’ based on the external form of the structure). This building may have been a model of the king’s palace and included fluted engaged columns (shown in the image above) in an entrance colonnade, an antechamber, and three small inner courts. This structure seems to have been a place where the king rested when he was visiting the complex for ritual actions during his earthly life.

These courts lead to a square chamber with a niche, which may have originally held a statue of the king. Some of the walls in this chamber were decorated with a frieze of djed symbols along the top. Djed symbols embodied the concept of “stability” in ancient Egypt, which the king was supposed to provide.

Heb Sed Court, viewed from north end, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

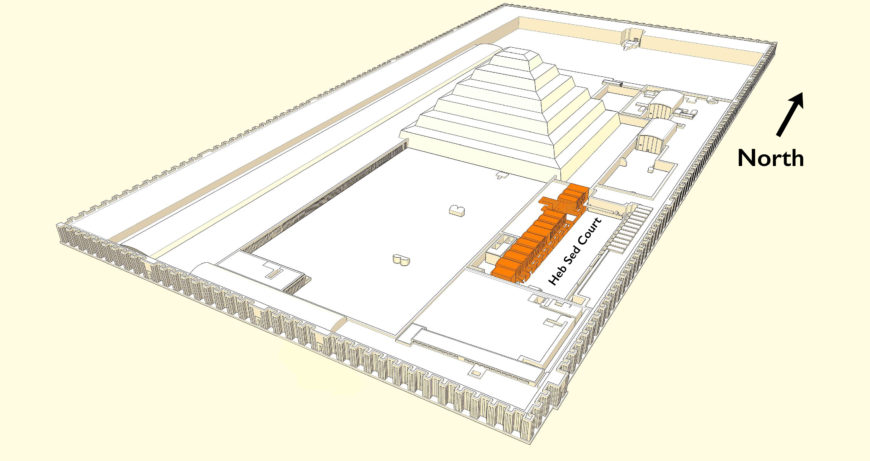

Heb Sed Court

Location of the Heb Sed Court in orange, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (Monnier Franck, CC BY 2.5)

Beside the T-Temple is a space known as the Heb Sed Court. The heb-sed was an important and ancient royal ritual that was performed to rejuvenate the king and reaffirm the pharaoh’s right to rule. This court was the symbolic realm of the ka; the actual heb-sed ritual may not have even been performed within Djoser’s lifetime in this location. The primary intent instead was to provide a place for the king’s ka to perform the rituals that would allow him to continually regenerate in the afterlife.

Hieroglyph for heb-sed, showing the dual thrones on a platform enclosed by a kiosk, from the White Chapel, Middle Kingdom (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

At one end of the Heb Sed court was a platform with two staircases, which was the focus of the space. This platform was so central to the ritual that its form became the hieroglyph for “Sed Festival.” The double-dias would have originally presented a pair of statues of Djoser enthroned as Lord of the Two Lands, wearing the White and Red Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The Heb Sed court was lined on two sides by dummy chapels dedicated to the deities of Upper and Lower Egypt. The prototypes for these stone chapels were light, wood-framed structures (they also appear as hieroglyphs). Each chapel was fronted by a baffle wall and had one small room that served as a sanctuary and likely held a statue. Otherwise, they are solid stone structures, with carved details that mimic doors, hinges, and pivots.

The shrines on the east side of the Heb Sed court are the typical shape of those from Lower Egypt, while most of those on the west have the distinctive shape of the shrines of Upper Egypt. All the shrines in this court are in actuality stylized renderings of ancient architectural forms that had been used for local sacred shrines along the Nile since the earliest times. Their presence is a clear indication of the desire to maintain these traditional architectural forms while they also function as icons to represent the extent of the Two Lands and the king’s ability to unite them.

North House and South House

Plan of Djoser’s Stepped Pyramid complex with the locations of the North and South House in orange, Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E. (plan: Franck Monnier, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A narrow passage at one end of the Heb Sed Court leads to two long courtyards running parallel to the Step Pyramid and separated by a wall. Within each of these courts is a large chapel, probably intended to represent a pair of archaic shrines belonging to the heraldic goddesses who embodied Upper and Lower Egypt—the vulture Nekhbet and cobra Wadjet, at (respectively) Hierakonpolis to the south and Buto in the north.

Frieze of khekher-signs and bundled shafts, South House, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

At the end of one court is the structure known as the South House. It was originally 12 meters in height and sported a banded cornice and a façade with 4 columns with bundled shafts (seen in the photograph with the khekher-signs) whose capitals have been lost but which were probably in the form of the heraldic plant of Upper Egypt, the lotus. At the top of the preserved wall is a sharply carved frieze of khekher-signs, a stylized fence motif known from earlier imagery that continued to be used as a protective element in tombs and temples for millennia.

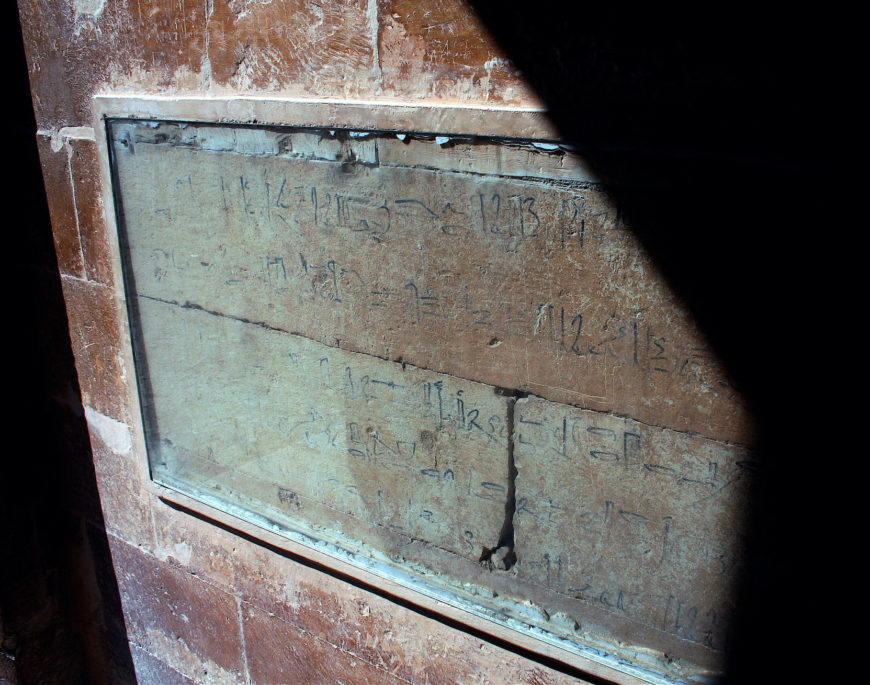

The off-center entrance passage of the South House leads to two 90-degree turns and a small sanctuary with 3 niches, which would have originally held statuary. On the walls of this passage is where later New Kingdom visitors to the complex recorded their admiration of Djoser and his monument in ink. Keep in mind that, at their time, this magnificent complex was already around 1,300 years old but was clearly still in relatively good condition and able to be visited.

The North House’s façade included columns and an off-center door like the South House. This corridor, however, led to a sanctuary with 5 niches. The façade included 3 engaged columns with triangular shafts and papyrus capitals with open umbles, mimicking the heraldic plant of Lower Egypt.

Both the North House and the South House probably represent places where the king’s ka could receive homage from his subjects after the heb-sed ritual of rejuvenation was complete.

Step Pyramid, viewed from the south, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The Step Pyramid

In its final form, the Step Pyramid was easily visible for some distance over the top of the enclosure wall and would have loomed large over the landscape (see the plan above). It was built in several stages, beginning as a traditional flat, rectangular tomb form typical for elite burials, called a mastaba (Arabic for “bench,” because of their shape). This original core, constructed of packed rubble covered over with finished, smooth limestone, was 63 x 63 meters and approximately 8 meters high.

The subsequent stages covered that mastaba by piling rough, inward-leaning stones on top and then encased that core in finely cut limestone to create a pyramid with 4 steps. The last major stage increased the pyramid’s height to 6 steps and its final height of nearly 60 meters. Approximately 330,400 cubic meters total of stone, clay, and other material was used in the construction of this immense monument.

Cut out plan of the Stepped Pyramid complex, with the 11 shafts (32 meters deep) and interconnected galleries (30 meters in length) indicated, Saqqara, Egypt (image: Franck MONNIER Bakha, CC BY-SA 1.0)

It has been suggested that the multiple building stages of the Step Pyramid were planned from the beginning. If so, the subsequent “burial” of the completed mastaba may have served a symbolic function as a reference to the buried, underworld aspect of existence after death.

A series of 11 shafts were carved on one side of the pyramid during the second stage of construction. These lead down to long interconnected galleries, that were apparently used as a tomb complex for royal family members. Of note is that radiocarbon dating of some of the bones indicates that at least one female buried here dates to several generations before Djoser’s time.

This older burial may be related to a massive cache of nearly 40,000 carved stone vessels that was discovered in these galleries (not pictured here). These vessels, made of various materials such as slate, diorite, and calcite, were also a variety of shapes. Unfortunately, the ceilings of the chambers had collapsed so many were broken to pieces, but those that remain intact show great creativity and skill in execution. Some of the vessels are inscribed with the names of different First and Second Dynasty kings (including Narmer). Some Egyptologists believe Djoser retrieved these vessels from earlier royal tombs that had been damaged and buried them in his own complex for safekeeping; others believe the vessels came from temple storehouses—exactly how and why they were gathered and deposited here remains unclear. These shafts were covered over during the next phase of construction and sealed off.

Serdab on north side of the Step Pyramid, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Serdab and temple to the ka

On another side of the pyramid was a “serdab” (Arabic for “cellar”) (see the plan above). This small, sealed chamber of finished limestone abutted the casing of the pyramid itself.

Left: eye holes (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0); right: lifesize statue of Djoser (replica); the original statue was removed to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (and subsequently to the G.E.M.), and the copy now sits in its place (photo: Alberto-g-rovi, CC BY 3.0), Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt

Beautifully preserved life-size painted limestone funerary sculptures of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret. Note the lifelike eyes of inlaid rock crystal (Old Kingdom) (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Within the chamber sat a life-size statue of the king carved in limestone and painted. Although inaccessible in the sealed chamber, this image of the king engaged with the outside world via two eye holes that allowed it to “see” out. Visitors could present food offerings and incense at a small altar before the holes, providing substance to the ka of the king to benefit him in the afterlife.

The king is depicted wearing the tightly-wrapped white cloak associated with the heb-sed ritual and a long wig covered by an early version of the nemes, the striped royal headcloth. He also sports a long false beard and one of the earliest mustaches ever depicted in sculpture. The eyes of the figure were originally inlaid, probably with painted rock crystal (like those of Rahotep and Nofret) and would have been surprisingly lifelike.

Also on this side of the pyramid was a cult temple for the king’s ka. This temple included two symmetrical interior courtyards. Access to the underground chambers was permitted via a sloping descending passageway that was found in the western court.

Descending passage to subterranean chambers under the Step Pyramid, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

King’s Burial Chamber

Burial vault, view of the roof of the chamber with the plug in place, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Leon petrosyan, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Under the center of the pyramid is the Central Shaft, a square passageway that is 7 meters on each side and 28 meters deep. At the bottom was a burial chamber carved of Aswan granite, a very hard stone that was both difficult to cut and had to be brought from the quarries in southern Egypt roughly 860 km away. Originally, the burial chamber had a ceiling lined with limestone and inscribed with five-pointed stars. This is the first preserved example of a ceiling type that became widely used for burial chambers from this point forward. These star-lined ceilings conceptually create a burial chamber roof that is “open” to the night sky even when buried within a mountain of stone.

The final burial chamber was carved of granite and had a cylindrical opening in the roof. This opening was blocked with a massive granite plug weighing 3.5 tons that was lowered into place using ropes. Once the king’s body was interred and the plug set into place, the descending corridor was filled with rubble and sealed off.

Although hidden away and completely inaccessible, the king’s burial chamber lying at the center of the pyramid served as the core of the entire complex and was the ultimate focus of all ritual actions in the enclosure. Through the ongoing rejuvenating festival represented by the Heb Sed court, the interactions between the living and the king’s ka in the structures around the pyramid, and the eternally occurring actions that were depicted in relief panels found in the Subterranean Chambers and South Tomb (discussed below), Djoser was symbolically set up for an eternity of renewal in an ideal afterlife. The whole memorial complex was designed for this primary function.

Subterranean Chambers

In addition to the king’s burial chamber, a labyrinth of tunnels totaling nearly 5.5 km in length was quarried out beneath the pyramid. There is a central corridor and two parallel ones that extend 365 meters. These are joined by a complicated tangle of underground galleries, shafts, and tunnels. The corridors connect a series of subterranean galleries—nearly 400 rooms in total!—including those that held the family burials and the cache of finely carved vessels of calcite and hard stone mentioned above.

Blue-green faience tiles, Blue Chamber, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Orell Witthuhn, CC BY-SA 4.0)

One suite of rooms was designed as a palace for the king’s ka to enjoy in the afterlife. The decoration of the walls is intended to look like a real structure and includes carved windows and doors. Called the Blue Chamber, this space is covered in thousands of molded blue-green faience tiles (no fewer than 36,000 were discovered in the complex) arranged and set in panels to mimic a building technique using reed matting that is known as wattle-and-daub. The blue-green color was not only brilliant but held regenerative symbolism connected to life-giving primeval waters. The color was also a visual allusion to the idyllic and symbolically potent “Field of Reeds.” This space was mentioned in later royal mortuary texts along with the earth and sky as domains the king was to receive in the afterlife.

Niche with panel showing Djoser walking towards the shrine of Horus of Behedet (modern Edfu), Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Juan R. Lazaro, CC BY 2.0)

Interspersed with these dazzling blue sections, on one wall were 3 large relief panels carved in limestone showing the king engaged in ritual actions. Some of these panels, like their parallels under the South Tomb, depict the king performing in the ritual race around the boundary stones that would have taken place in the South Court. These reliefs were never intended to be seen by the living but instead provided a form of perpetual communication between the king and the gods, where he continuously performs perfect rituals designed to renew him, Egypt, and the cosmos itself.

South Tomb

A mysterious structure in the great South Court, called the South Tomb, is considered a type of “second tomb” for the king’s ka. The superstructure is topped with an elegantly-carved frieze of rearing cobras, known as uraei. Uraei were important protective symbols in ancient Egypt and often represented the goddess Wadjet, the divine guardian of Lower Egypt.

South Tomb in orange, 84 x 12 meters, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (image: Franck MONNIER Bakha, CC BY-SA 1.0)

Beneath the superstructure, a deep shaft of identical dimensions to the one inside the Step Pyramid extends 28 meters down. Like the Central Shaft, this one ends in a square, granite vaulted chamber with a round opening that was blocked with a huge granite plug. However, this space is far too small to be an actual burial chamber for an inhumation. It could have served a purely symbolic function or been the burial place for the king’s viscera, the royal crowns, or other equipment the king wanted access to in the afterlife—we simply do not know. One one side of the shaft is a suite of rooms for the royal ka. In structure and design, these closely mirror the blue-tiled rooms with relief panels found underneath the pyramid.

Passageway leading down to the South Tomb, Stepped Pyramid complex, Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

All the essential features of the substructure of the Step Pyramid were replicated in the South Tomb—the descending corridor, central shaft with granite vault, and king’s palace with blue-tiled walls, and relief panels of the king performing ritual actions. However, the South Tomb appears to have been completed before the substructure of the Step Pyramid and its purpose is still unclear. It may have been viewed as a symbolic tomb connected with the important heb-sed ritual, and involved a ritual “death” of the king. It was probably the precursor to the satellite pyramids that were part of later royal pyramid complexes, such as that of Khufu. It was also likely a reference to earlier royal mortuary practices.

The door to new ideas

Djoser and Imhotep opened the door to new ideas. The Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara is a vital crux that represents both the culmination of royal funerary architectural development of the 1st to 2nd Dynasties and the spark of Egypt’s glorious Age of the Pyramids that would follow. Experiments in pyramid building continued during the next several reigns, reaching its pinnacle with the Great Pyramid of Khufu.

Additional resources:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline

Art in the Age of the Pyramids

Photo-filled report from Business Insider

Kathryn Bard, An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, 2nd ed.(London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015)

Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids (London: Thames & Hudson, 2008)

David O’Connor, Abydos: Egypt’s First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009)