Ming dynasty (1368–1644): an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 41

Art in Ming dynasty China

This is the tomb of the Hongwu Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (Taizu), founder of the Ming Dynasty who was buried in the undisturbed tumulus in 1398. View over bridge to Soul Tower, with restored roof. Xiaoling Tomb, begun 1381, Nanjing, China (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For centuries, China had been ruled by the foreign Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), but by 1368 Yuan rule was disintegrating, due in large part to civil unrest. A shepherd, monk, warlord, and bandit named Zhu Yuanzhang sent his armies to take the Yuan capital at Dadu (now Beijing, which means “Northern Capital”) and expel the remaining Mongols from the city. He then claimed the “Mandate of Heaven ” or the heavenly right to rule (tīanmìng 天命), and installed himself as the first emperor of the Ming dynasty (the Hongwu emperor) in the city of Nanjing (“Southern Capital”). Once again, a Han Chinese dynasty ruled China.

Map of the Ming Empire c. 1580 (Michal Klajban, CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of the first things the new emperor did was to begin work on the construction of his mausoleum (shown above)—an impressive tomb complex intended to memorialize his reign and ensure his status in the afterlife. This tomb, which has never been opened, is accessed by a processional path punctuated by monumental gates, courts, and lavish sculpture.

Aerial view of the Forbidden City, Beijing (© Google Earth 2021)

In 1421, the third emperor of the Ming dynasty moved the capital back to Beijing to build a new power base, where the government constructed a massive new imperial city according to Chinese cosmological principles (known today as the Forbidden City). Beijing is located near the Great Wall of China, a physical and cultural demarcation between China and the northern tribes that frequently posed a threat to the country, and so the site was of great strategic importance. Moreover, since Beijing was a capital during the Mongol Yuan dynasty, the construction of a new administrative complex that reflected ancient Chinese practices also conveyed a message of legitimacy.

It is useful to think about the artistic production of the Ming dynasty as intersecting realms: art made for the imperial court and art made outside the court. The courtly realm includes the objects created for the ritual cultures of the Ming rulers, such as ceramics from the imperial kilns or paintings from the imperial academy. However, there were other scholars and officials who did not work as court artists, and they immersed themselves in literary and garden culture, producing calligraphy and paintings and refining landscape design and objects for their studios. These artists increasingly turned to portraiture to memorialize the dead and communicate social status in life during the Ming dynasty. At the same time, objects such as porcelain and silk—produced both inside and outside of the court—expanded in global circulation.

Watch a video and read introductory essays about the Ming dynasty

The tomb of the first Ming emperor: Journey to the Purple Mountain and the burial of the first Ming emperor.

Read Now >

The Forbidden City: Covering 178 acres, this gated complex was a “golden cage” for China’s emperors and courtiers.

Read Now >/3 Completed

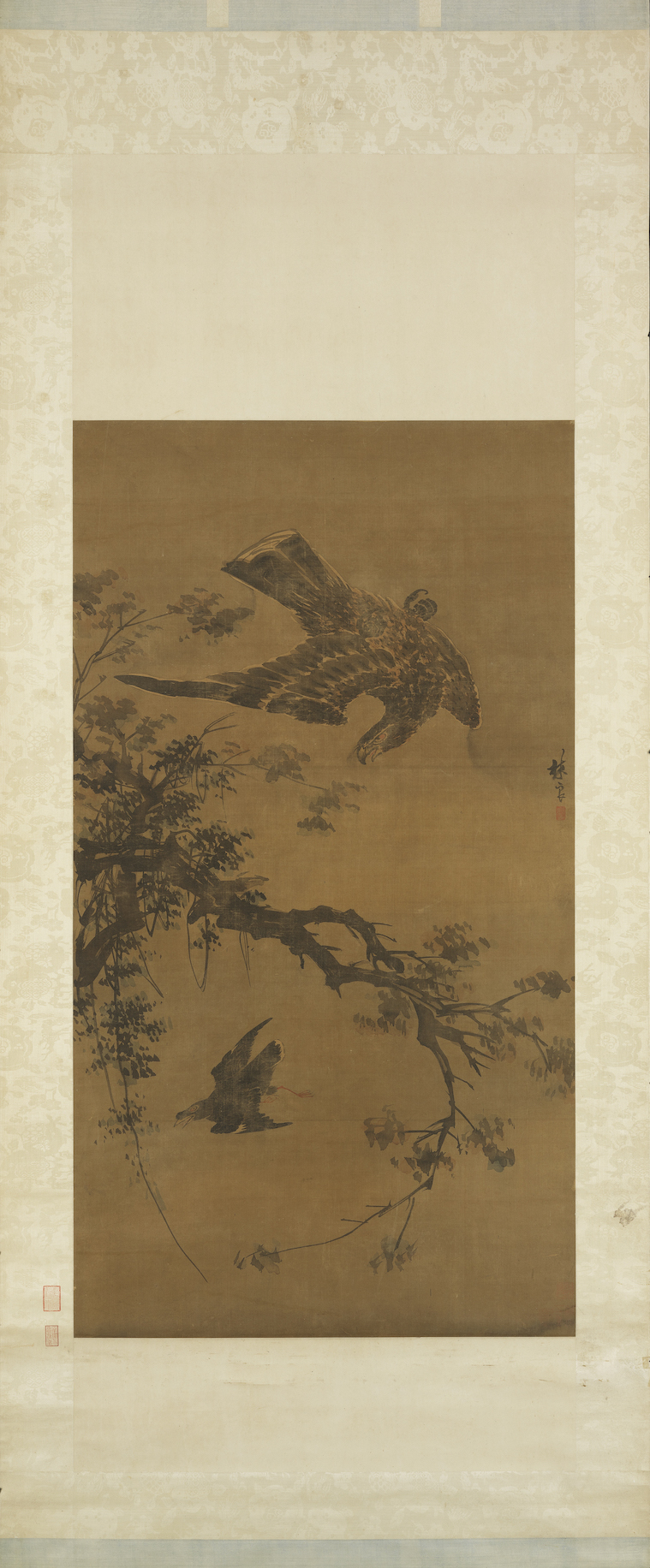

Ritual Culture

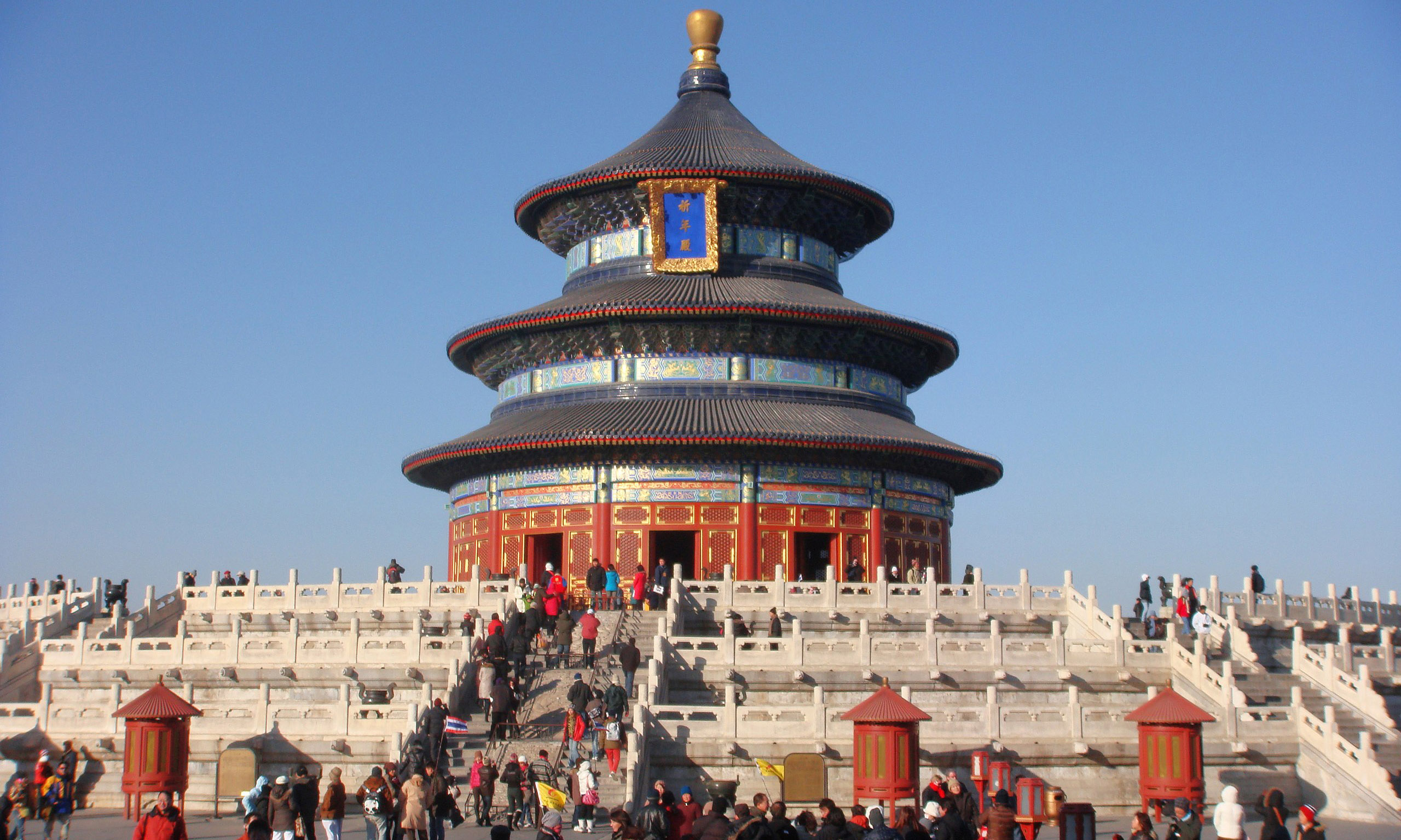

The Temple of Heaven, Beijing, China (photo: UNESCO)

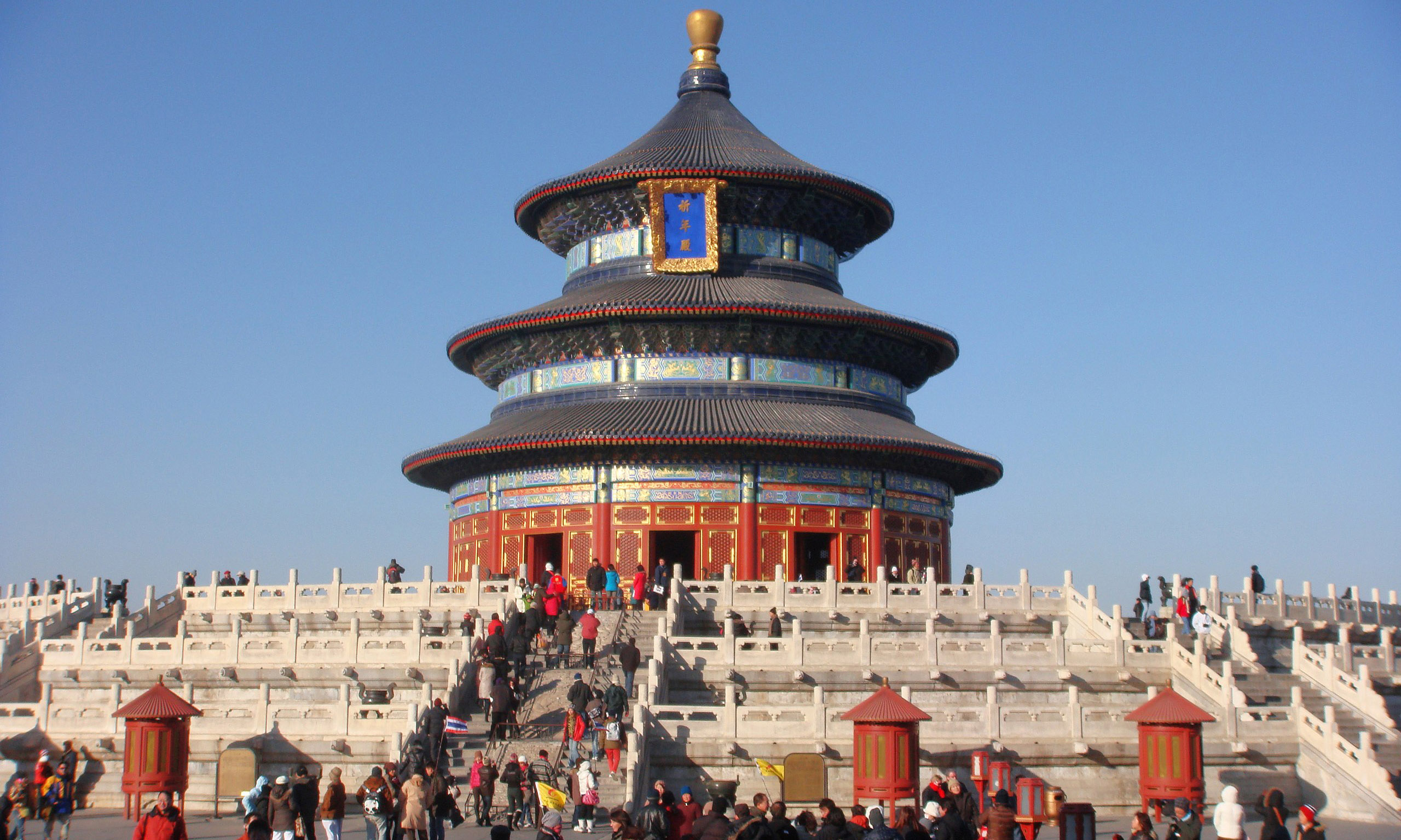

The Ming court commissioned large-scale architecture and objects (such as ceramics and paintings), for ritual purposes. In the capital of Beijing, the imperial altar known as the Temple of Heaven demonstrates the importance of court rituals for maintaining harmony: the emperor, as the Son of Heaven, made sacrificial offerings that were believed to ensure a good harvest for the empire. The emperor would present the offerings in bronzes and ceramics designed specifically for ritual use, often bearing colors that symbolize heaven (blue), earth (yellow), sun (red), and moon (earth). In the Ming dynasty, vermillion red had special importance as the color of the Ming dynasty, for the name of this particular red (zhu 朱) was also the surname of the ruling family.

Sakyamuni, Lao Tzu, and Confucius, Ming dynasty, 1368–1644, ink and color on paper, China, 61.5 x 59.9 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1916.109)

Neo-Confucianism, a philosophical system originating in the writings of Confucius, dominated court life. This view placed paramount importance on the organization of society, and through proper rites and rituals. However, Buddhism (which focused on merit/karma and salvation), and Daoism (which emphasized the relationship between nature and humanity), also had their place in the religious and spiritual practices of society. These “Three Teachings” existed harmoniously in the Ming dynasty, as we see in a painting showing the three founders of these philosophical and spiritual traditions.

Watch videos and read an essay about ritual culture

A ritual Ming dish: the name of this red (zhu 朱) was also the surname of the ruling family.

Read Now >

Shakyamuni, Laozi, and Confucius: The composition of the painting seems to have borrowed depictions of the Three Laughers of Tiger Creek, a popular allegorical story about the meeting of three famous figures.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Academic Painting

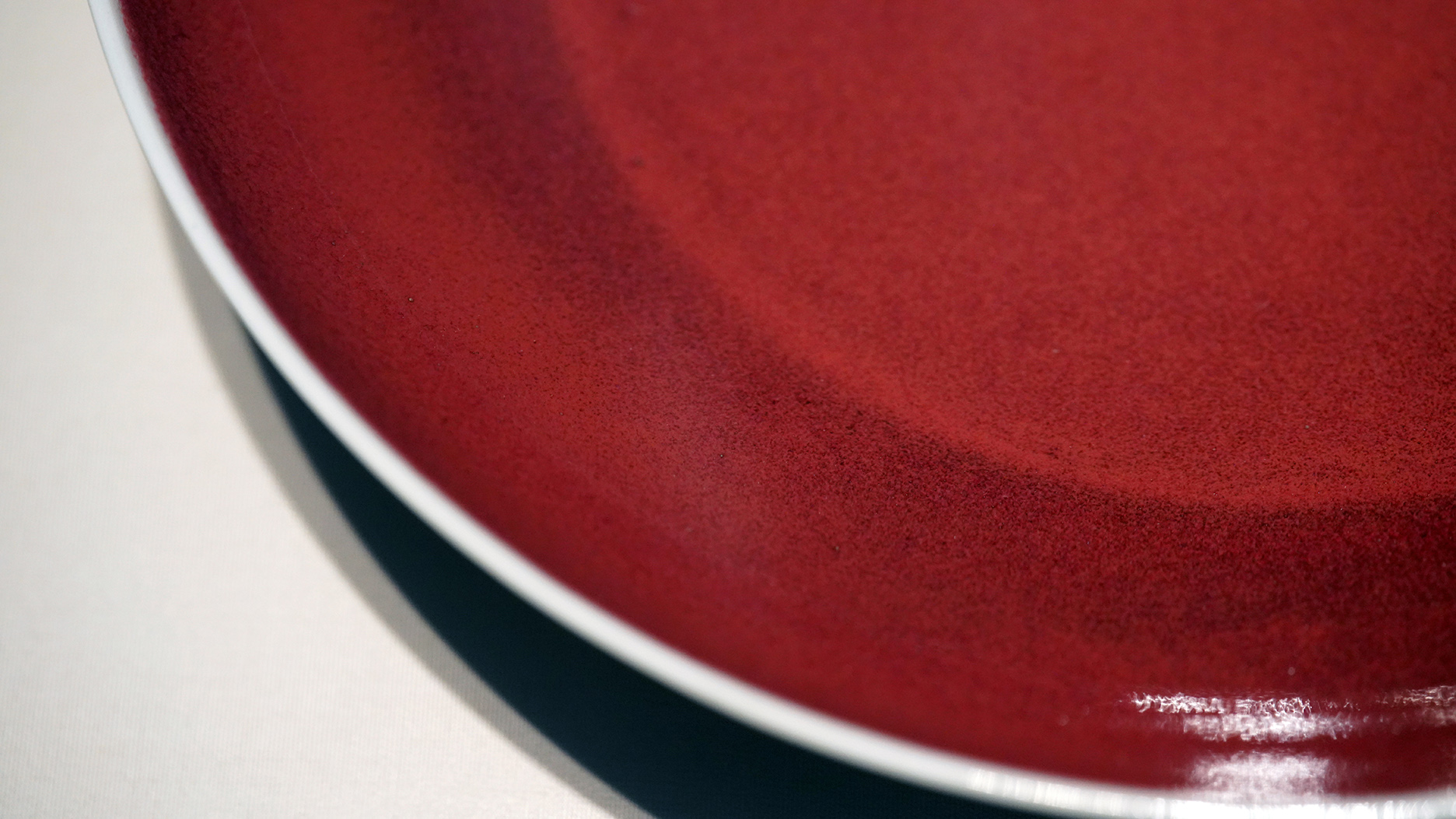

Lin Liang 林良 (c. 1416–80), Autumn Hawk, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 136.8 x 74.8 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

In addition to creating ritual objects and architecture, the Ming court also employed professional painters in workshops known as the imperial academy. Particularly in the first half of the dynasty, Ming court painters looked back to the Southern Song academy for inspiration (the period prior to the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty). For instance, the notion of the “Three Perfections,” or the harmony of painting, poetry, and calligraphy emerged during the Song dynasty. Paintings also often display the neat fitting of elements into small spaces, like architecture or rocks, to suggest a coherence of space in an asymmetrical composition.

Ming artists demonstrate their engagement with Southern Song art with their meticulous portrayals of subjects such as birds and flowers that often symbolized scholarly or military themes, such as Autumn Hawk by Lin Liang. In this hanging scroll, a hawk appears to swoop through the hazy autumnal air in fierce pursuit of a blackbird beneath a branch that mimics the twisted body of the hawk. The crackling power of the brushwork and the drama of the forms creates an impression of the delicate balance between life and death. The notion of reclaiming a Han Chinese-ruled dynasty after the Mongol Yuan empire likely motivated court artists’ interest in reviving Song-dynasty subjects and styles, as also seen in Palace Women and Children Celebrating the New Year.

Read an essay about an academic painting

Palace Women and Children Celebrating the New Year: The painting captures the joyful moments as imperial women (the wives and concubines of the emperor) and their children celebrate the arrival of the Chinese New Year.

Read Now >/1 Completed

The Zhe School

Professional painters outside of the Ming court, known as the “Zhe School” (short for Zhejiang, the area of the former capital of the Southern Song court), similarly revived Southern Song court styles, but with a focus on landscape.

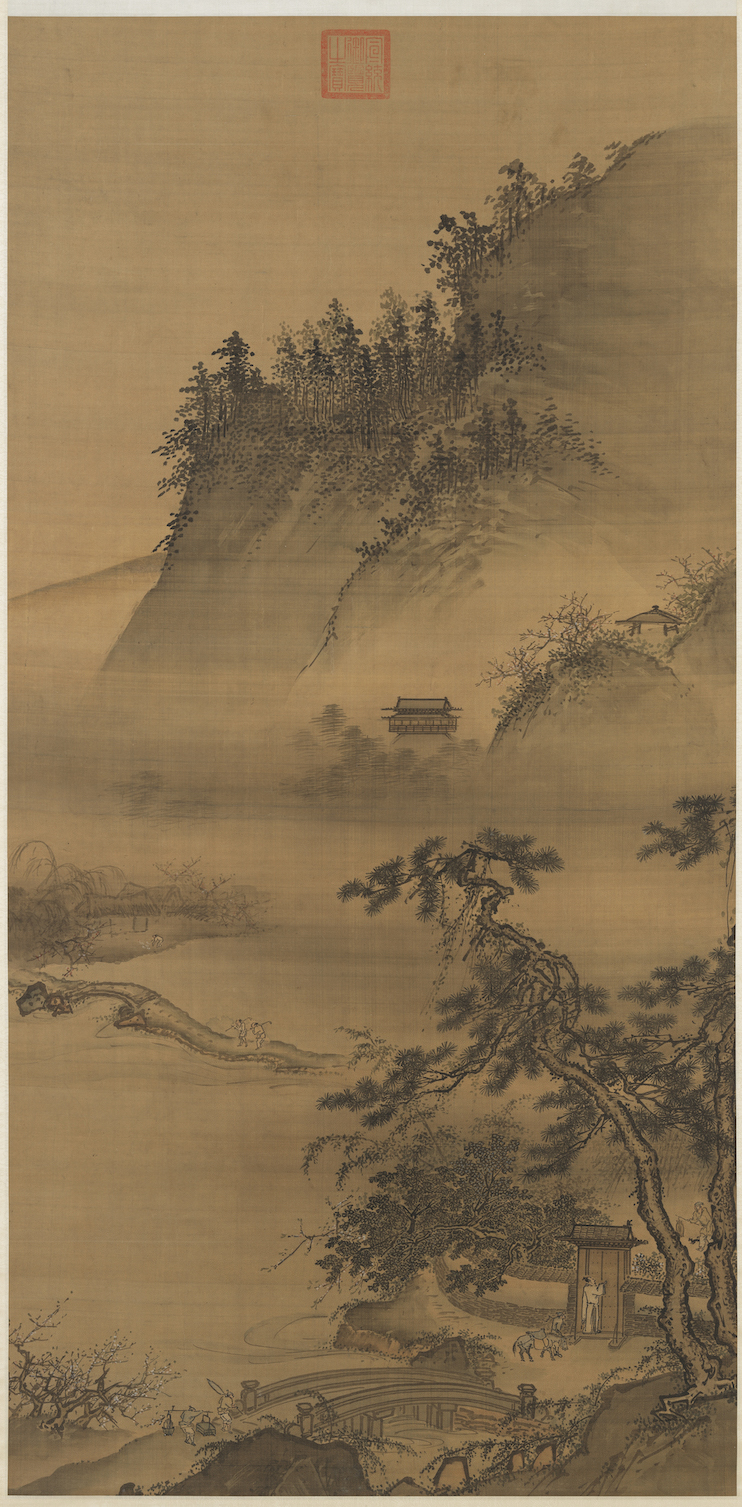

An example of a Zhe School painting. Dai Jin, Returning Late from a Spring Outing 春遊晚歸, hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 167.9 x 83.1 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Key features of Zhe School paintings typically include axe-cut brushstrokes, one-corner compositions, and the stark contrasts of light and dark of Southern Song academy paintings, but with slightly more emphasis on humans (usually travelers) and narrative or architectural features in landscapes than seen in Song paintings. In fact, Ming academic styles often seemed indistinguishable from Southern Song court paintings—so much so that works that scholars initially believed to be from the Southern Song were later re-attributed to Ming dynasty painters.

Scholarly Arts

Largely excluded from government posts during the Yuan dynasty, educated Chinese men studied the classics and practiced calligraphy to pass civil-service examinations during the Ming dynasty. However, some of these literati (men of letters) retired from their posts early or did not pursue an official career at all, and instead opted to spend their days engaging in the visual arts as a leisure pastime. Familiar with the “four treasures of the study” (brush, ink, paper, and inkstone), many became well-known artists who circulated their painting and calligraphy among their friends.

Garden of the Humble Administrator, Suzhou, China (photo: Caitriana Nicholson, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Many scholar-officials and professional artists (those working outside of the court) resided in the south, in particular the city of Suzhou, an economic and artistic center transformed by urbanization under the Ming. As the city grew increasingly dense, people had to find places for nature and leisure within the city, giving rise to garden estates along its many canals. The idea of using gardens for anything more than places to grow things (like orchards) was a new concept in the sixteenth century, when gardens came to be regarded as microcosms of nature outside. Garden owners (typically scholar-officials, but also merchants) hosted gatherings and engaged in the “four arts of the scholar,” or music, chess, calligraphy, and painting. Gardens did not need to be large—these carefully constructed spaces had corridors and pavilions where one could enjoy music, write poetry, study, meditate, or converse with friends.

The Wu School

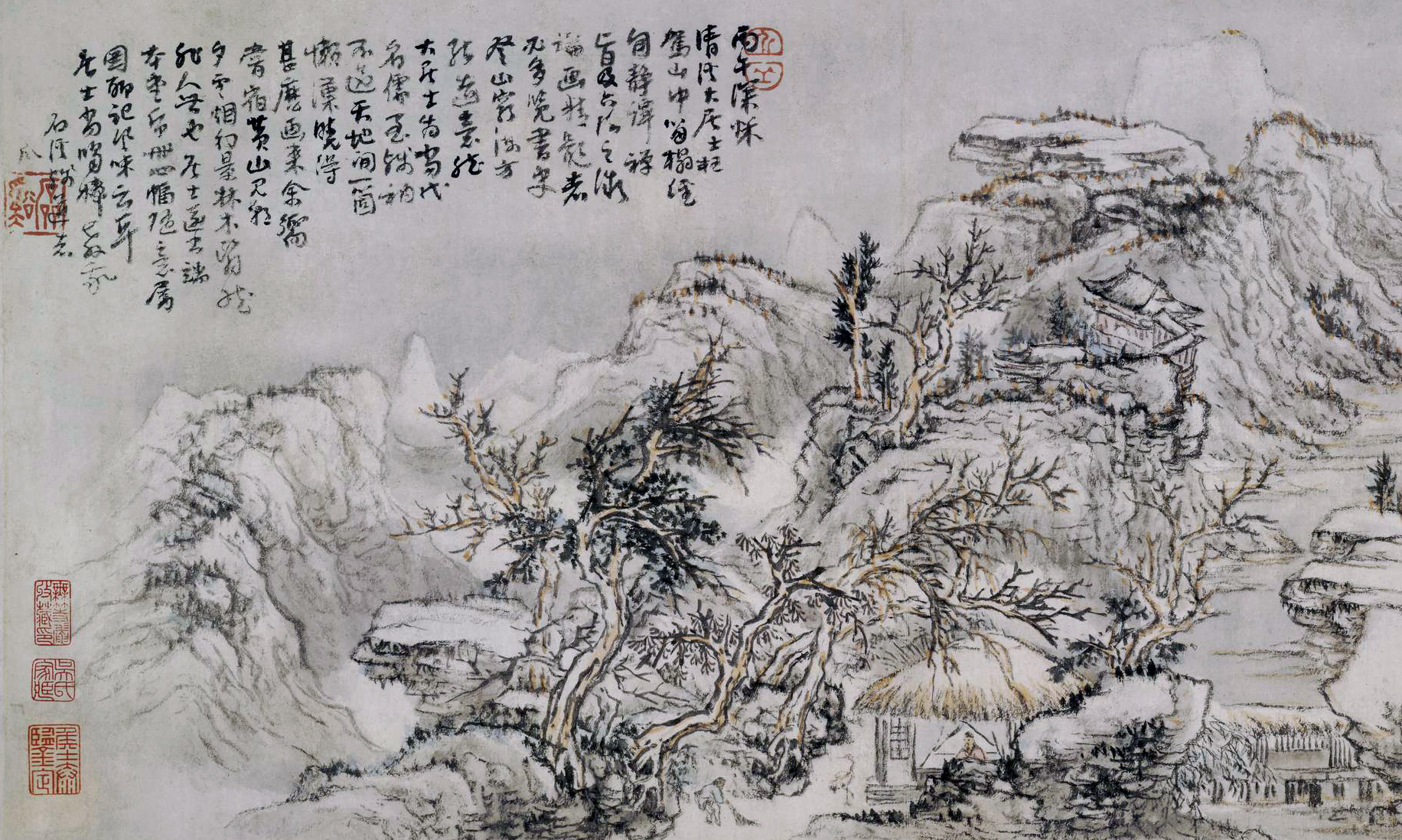

The area around Suzhou is known as the ancient Wu region, which gave rise to the “Wu School,” a circle of artists active in Ming dynasty Suzhou who studied the landscapes, calligraphy, and poetry of former masters. Shen Zhou, a collector, painter, and calligrapher, is known as the founder of the Wu School.

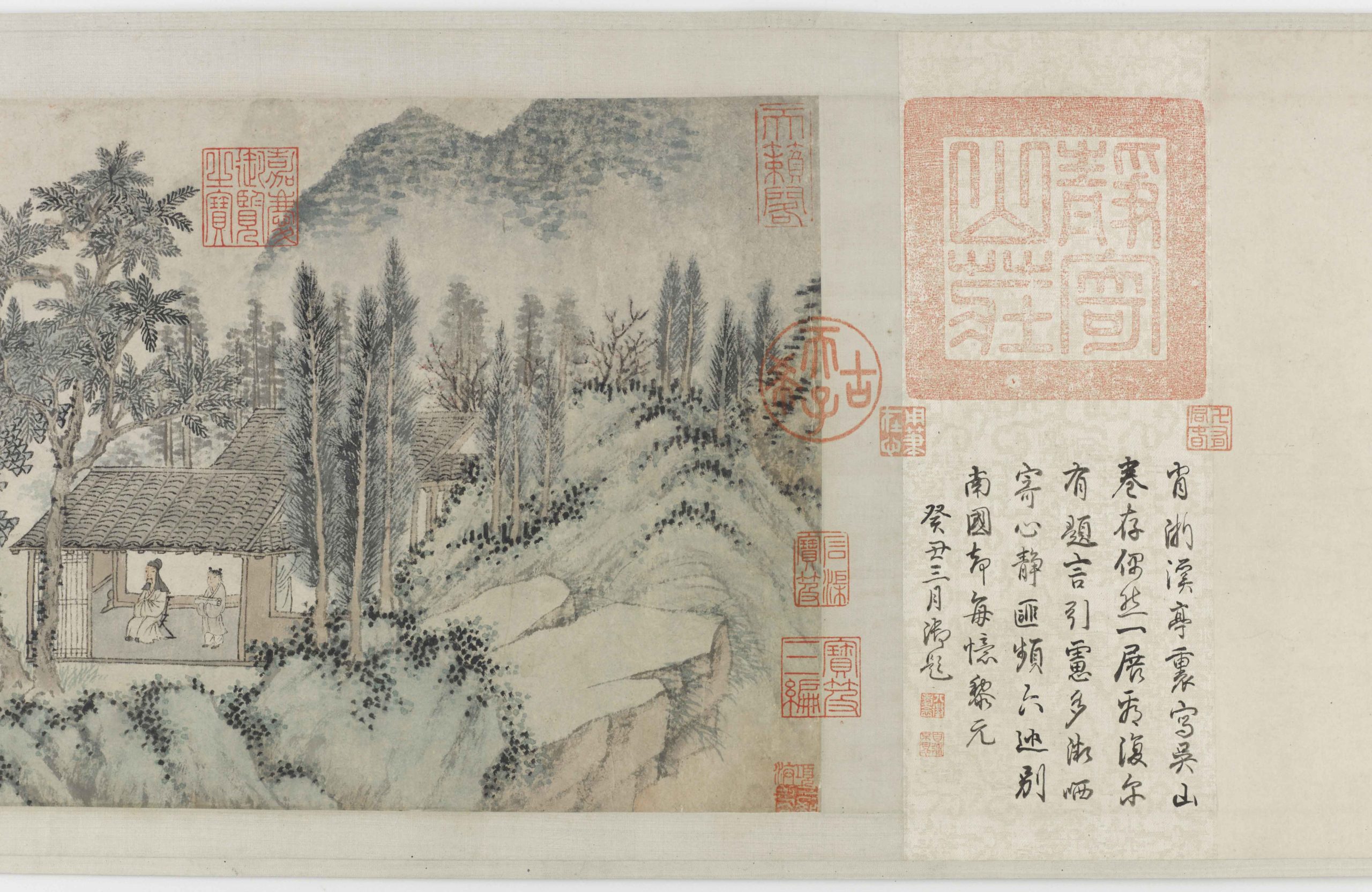

Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427–1509), A Spring Gathering, attached calligraphy by Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427–1509), frontispiece, inscription on front mounting, and three inscriptions on the painting by Hongli, the Qianlong emperor (1711–1799, reigned 1735–1796), colophon by Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470–1559), Ming dynasty, c. 1480?, Wu School, ink and color on paper, China, 26.5 x 131.1 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1934.1)

He often pictured garden subjects or landscapes characterized by pale pink and blue hues, adding calligraphy to enrich the content of the image and to add a self-expressive aspect. This distinguished the work of Wu School painters from court painters, who often would not sign their works because they were created in service of the court, rather than for reasons of leisure, self-cultivation, or social obligation.

Ready essays and watch a video about scholarly arts

Wang Lü, Landscapes of Mount Hua (Huashan): Wang Lü climbed the sacred Mount Hua and recorded that journey, emulating Southern Song painters, in this 40 leaf album.

Read Now >

Master of the (Fishing) Nets Garden: Every inch of this contemplative space was carefully crafted—there’s bamboo, patterned paving, and scholar’s rocks.

Read Now >

Shen Zhou, A Spring Gathering: Artists during the Ming dynasty often honored their patrons by portraying them in a garden studio.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Portraiture

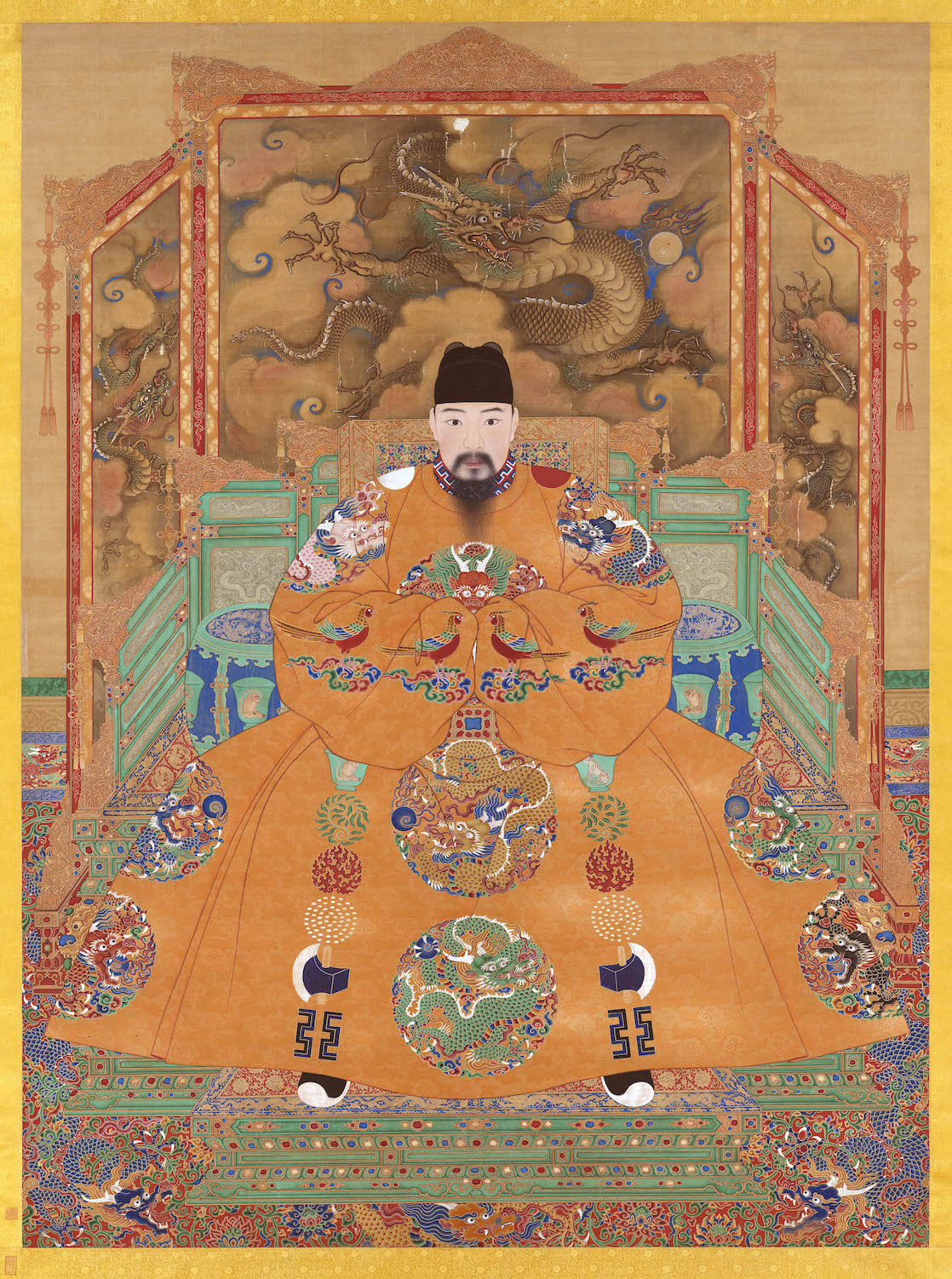

Portrait of the Hongzhi Emperor, 15th century, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 208.6 x 154.3 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

During the late Ming dynasty, artists took particular interest in portraiture, which was used to express social status—inside or outside of the court, and in life or death. Portraits of ancestors (usually made posthumously) performed the Confucian principle of filial piety (the duty to provide for one’s ancestors) while also reflecting the fashions of the time in their stylistic conventions. Seen by only a few—usually family members—portraits were meant to venerate the ancestor depicted in the images. Portraits likely were hung for a specific moment such as in the New Year for ceremonial family rituals, and inspired awe and devotion by presenting the deceased in an otherworldly level of existence: the revered position of ancestorhood. Workshops of two or more artisans typically produced the portraits. Specialists were assigned to the face and the body because the face needed to be an accurate copy, in line with Chinese concerns for facial physiognomy, to resemble an individual and their distinctive features. In contrast, the body appeared flat and schematized, bearing appropriate court insignia, such as the portrait of the Hongzhi emperor (Ming Xiaozong).

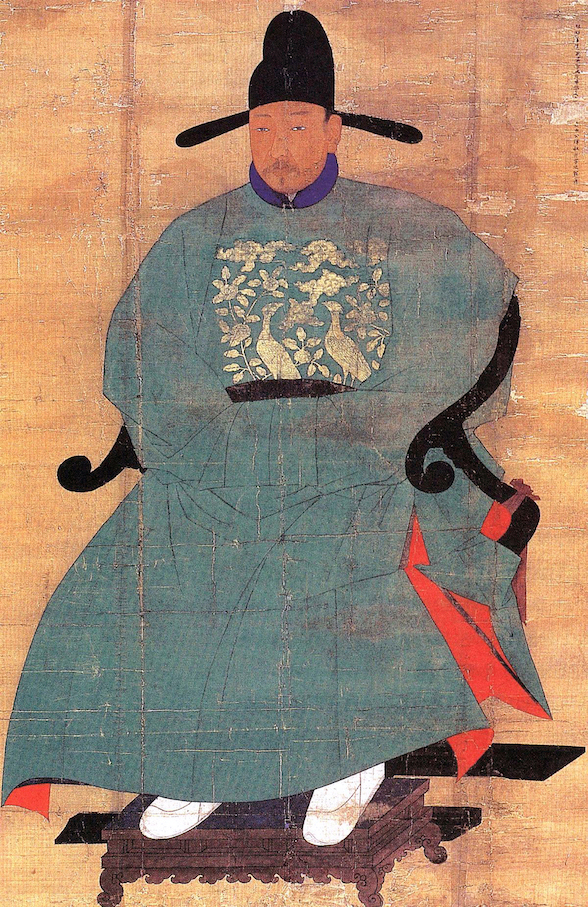

Portrait of Sin Sukju, second half of the 15th century, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 167 x 109.5 cm (Goryeong Sin Family Collection, Cheongwon, Treasure no. 613)

During this period, there was a close alliance between the Ming dynasty and Joseon dynasty Korea through trade and diplomacy, as well as their shared Confucian values. It is therefore no surprise that ancestral portraits also appeared in Korea—with the similar purpose of commemorating the deceased through careful attention to rank and status.

Chen Hongshou 陳洪綬 (1598–1652) and studio, An Immortal Under Pines, dated 1635. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 202.1 x 97.8 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

In addition to formal ancestral portraits, artists also created informal paintings of themselves, their friends, and patrons. Although their stylistic conventions differed from ancestral portraits, the display of prestige and status also motivated these works. The self-portraits of professional painters (those who were commissioned outside the court) demonstrate the profound changes in Ming dynasty society, where cities like Suzhou became wealthy and cosmopolitan urban centers. In one such painting attributed to Chen Hongshou, the artist appears to present himself using the portraiture convention of a pine tree, scholar, and rocks. However, the frontal gaze of the figure and otherworldly shapes of the landscape elements suggest that Chen was highly attuned to the mythologizing functions of traditional portraiture—and perhaps was even mocking them. Like Chen, artists forged viable professions outside of the court by painting for private patrons, and often created their own social circles of artists and art-lovers.

Read about a portrait in Korea that borrows from Chinese conventinos

Portrait of Sin Sukju: Like in China, portrait paintings commemorated the sitter in both life and death in Joseon Korea.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Global Realms

While its cultural and economic centers thrived, the Ming dynasty amassed a powerful, global empire extended by trade and exploration. As sea routes replaced the Silk Roads, cultural exchange during the Ming dynasty widened to include Mughal India, Southeast Asia, Africa, and beyond—trading silk, spices, and tea for imports such as silver, horses, and exotic animals. One emperor sent the explorer Zheng He on seven voyages that opened new diplomatic channels and carried Chinese objects to distant lands. In addition, Ming China sent exotic goods of ivory, silk, and porcelain to the Philippines for the Manila Galleon trade (intended for distribution throughout the Americas and Europe, via ports in what is today Mexico), and returned with silver from the Americas. Underwater excavations of sunken ships carrying cargo continue to reveal the extraordinary scope of these global encounters during the Ming dynasty.

Canteen, Ming dynasty, early 15th century, Jingdezhen ware, porcelain with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze, China, Jiangxi province, Jingdezhen, 46.9 × 41.8 × 21.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1958.2)

Perhaps most iconic are the blue-and-white porcelains that dominated the ceramic trade as early as the fourteenth century. Although blue-and-whites had been produced prior to the Ming dynasty (such as the famous David vases), it was in the fourteenth century that the site of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, began to produce official underglaze blue porcelains for the court. Jingdezhen is known for its kaolin clay, which was used to make porcelain—the hard, white, translucent body that was then dried, hand painted with cobalt blue, covered with a clear glaze, and finally fired at high temperatures to produce stark contrasts. Shapes often imitated Persian styles, while materials such as cobalt came from Central and West Asia.

‘Kraak’ bowl with armorial designs and inscription, Ming dynasty, about 1600–1620, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, objects from Ming China were among the most sought-after export items in Europe, yet they also responded to broadening cultural exchange. Patrons commissioned European designs on porcelains, as seen on the armorial-style shields and hydra on a “Kraak” bowl that appeared in Portugal, Holland, and Iran—even carved onto the stone façade of St. Paul’s Cathedral that was built by Jesuits in Macau, a Portuguese trading center in the seventeenth century. European artists captured the allure of Ming China in many ways, such as incorporating Chinese motifs on tapestries and even experimenting with porcelain production themselves—not always successfully, as the Medici have shown! Nonetheless, these transcultural works demonstrate the expansive, innovative, and imperfect realms of encounters and exchanges with Ming dynasty China.

Read essays and watch a video that address global realms

Canteen, from Jingdezhen: The material of white porcelain decorated with cobalt (blue) designs was a Chinese invention.

Read Now >

‘Kraak’ bowl, from Jingdezhen: This specific design appears in seventeenth-century Portugal, Holland, and Iran, suggesting that specially commissioned wares could also be sold more widely in the late Ming dynasty.

Read Now >

The Abduction of Helen tapestry: An ancient Greek story on a tapestry made in China, for export back to Portugal.

Read Now >

Medici porcelain: The powerful Medici family of Florence tried—and failed—to make true Chinese porcelain in the 16th century.

Read Now >/4 Completed

From the colorful ritual objects of the court to the calligraphy and cool hues of garden culture, there is no singular definition of Ming art. As urbanization shaped new relationships between man and nature, and trade shifted from land to sea, the material and visual culture of the Ming dynasty expanded both broadly and globally. As the empire of “Great Brightness” (Da Ming 大明), the Ming dynasty illuminated new realms for artistic production and creativity in daily life.

Key questions to guide your reading

In what ways did the arts shape the ritual life of the Ming court?

What types of art forms define Ming dynasty garden culture?

How did the vibrant overseas trade of the Ming dynasty contribute to world art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowIn what ways did the arts shape the ritual life of the Ming court?

What types of art forms define Ming dynasty garden culture?

How did the vibrant overseas trade of the Ming dynasty contribute to world art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

four arts of the scholar

four treasures of the study

Zhe School

Wu School

ancestral portrait

blue-and-white porcelain

Learn more

Craig Clunas, Empire of Great Brightness: Visual and Material Culture of Ming China, 1368–1644. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2007.