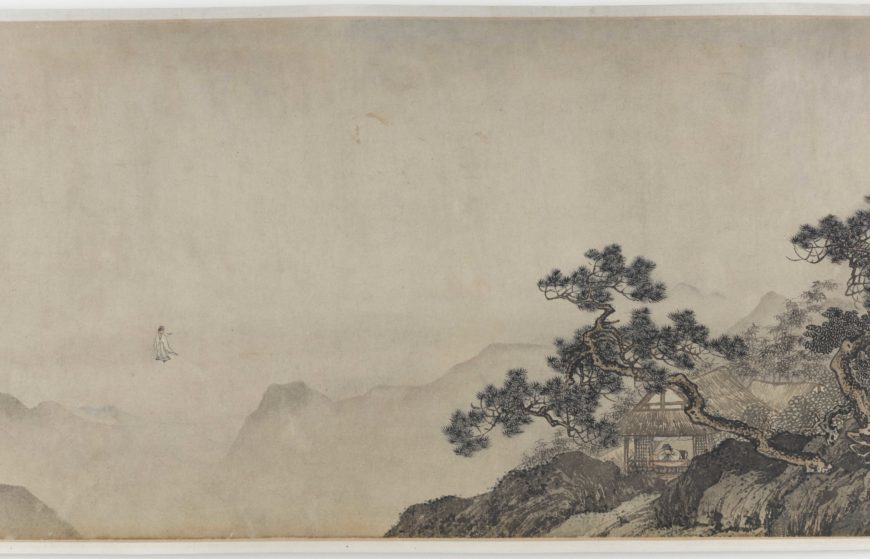

Tang Yin 唐寅 (1470–1524), The Thatched Hut of Dreaming of an Immortal, Ming dynasty, early 16th century, ink and color on paper, China, 28.3 × 103 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1939.60)

After nearly a hundred years of Mongol rule, China returned to native rulership in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The Ming was founded by a commoner, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398), who established Nanjing as his capital. However, nearly fifty years later, the third Ming emperor relocated the capital to Beijing, which has remained China’s main seat of government ever since. The Ming dynasty’s almost three hundred-year span witnessed unprecedented economic and cultural expansion and the near doubling of its population. The last century of the Ming, however, was besieged by border troubles, crop failure, fiscal instability, and court corruption leading to an overthrow by Manchu invaders from the north, who took Beijing in 1644.

During the Ming, most people believed simultaneously in multiple gods and followed the Three Teachings of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism. Commoners and emperors alike supported temples and honored devotional images in their homes. In addition, overland and maritime trade routes kept China open to followers of Islam and allowed for the arrival of European Christians.

Notable Ming achievements include the refurbishment of the Great Wall to its greatest glory, large naval expeditions, vibrant maritime trade, and the rise of a heavily monetized economy. Vital cultural achievements included the production of exceptional—and often colorful—porcelains, paintings, lacquers, and textiles, which created a dazzling visual world. The rise of the novel as a popular literary genre, accompanied by affordable illustrated books, brought literature to many. As a result of cultural achievements and economic achievements, the Ming saw a larger consumer base for luxury goods than any earlier period.

Canteen, Ming dynasty, early 15th century, Jingdezhen ware, porcelain with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze, China, Jiangxi province, Jingdezhen, 46.9 × 41.8 × 21.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1958.2)

In south China in Jingdezhen, kiln workshops during the Yuan dynasty had already produced large amounts of porcelain, but the city’s position as the main ceramic supplier for both domestic and foreign markets was solidified during the Ming. Judging from its broad distribution, Ming “blue-and-white” porcelain (white body decorated with cobalt-blue painting under the glaze) was the dominant ceramic ware around the globe. Especially in the early to mid-Ming period, many porcelain shapes and decorative schemes drew inspiration from the Islamic world, which had helped create a taste for a blue-and-white palette. The finest porcelains were commissioned by emperors for palace use and as gifts, including for foreign diplomats. Beyond blue-and-white, the palace also commissioned stellar monochromes, especially red, and promoted a new development of exquisite overglaze enamel decoration on porcelain.

Incense burner in shape of a tripod (li) with design of lotus, Ming dynasty, Hongzhi or Zhengde reign, 15th or early 16th century; 14th century jade knob, Enamels, brass, wire (cloisonné); with later gilt metal handles, wooden cover with Yuan dynasty jade knob, China, 18.4 × 19.4 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1961.12a-b)

Another type of enamelware greatly admired by the court was cloisonné, a technique which originated outside of China, but by the Ming was manufactured in China according to local taste. In this technique, a worker attaches thin metal strips to a metal base outlining all the details of a design, and then fills the empty cells (cloisons) with colored enamel pastes. Fired to a high heat, the enamel pastes are transformed into an opaque, glass-like surface.

Formerly attributed to Yan Liben (c. 600-674), Palace Women and Children Celebrating the New Year, Ming dynasty, 15th-16th century, ink and color on silk, China, 160.3 x 106.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1916.403)

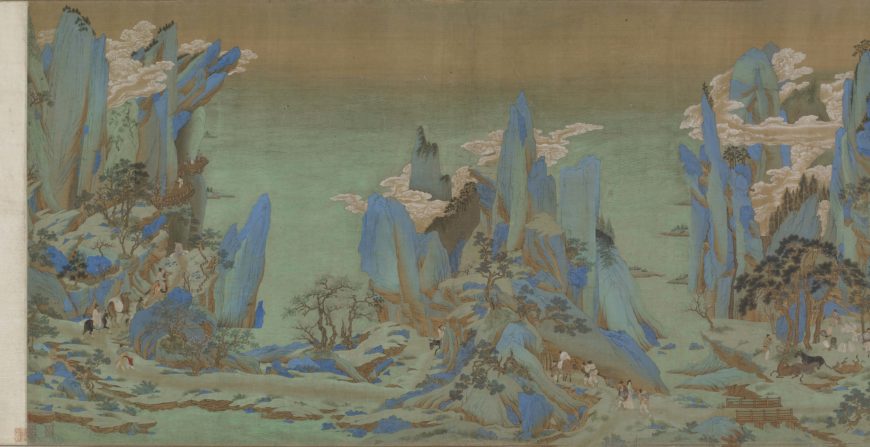

In the first half of the Ming dynasty, the court actively recruited painters from across the empire to serve in an academy producing works on themes that acclaimed the court’s majesty and glory. The emperors favored a representational style that revived many features from the Southern Song Imperial Painting Academy. Palace painters excelled in religious themes, moralizing narrative subjects, auspicious bird-and-flower motifs, and large-scale landscape compositions. Simultaneously, outside the court, scholar-artists were more self-expressive in their brushwork based on training in calligraphy, which continued a style promoted by Yuan dynasty literati-artists.

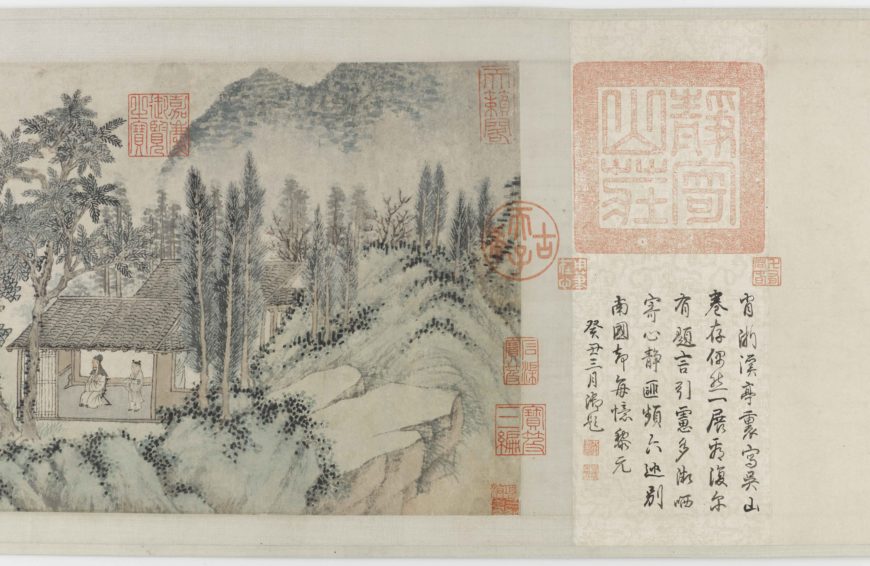

Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427–1509), A Spring Gathering, attached calligraphy by Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427–1509), frontispiece, inscription on front mounting, and three inscriptions on the painting by Hongli, the Qianlong emperor (1711–1799, reigned 1735–1796), colophon by Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470–1559), Ming dynasty, c. 1480?, Wu School, ink and color on paper, China, 26.5 x 131.1 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1934.1)

By the sixteenth century, a decline in imperial patronage and rapid economic expansion in south China created a new clientele for art, including landowners and wealthy merchants, many of whom wanted images that portrayed the cultivated lifestyle of a scholar.

Copy after Qiu Ying 仇英 (c. 1494-1552), Playing the zither beneath a pine tree (detail), Ming dynasty, late 16th-early 17th century, ink and color on paper, China, 22.2 x 105.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1953.84)

Many literati and professional painters lived in the same cities seeking support from the same patrons, which led to greater synergy and fusion between their painting styles as exemplified by the professional painter, Qiu Ying (ca. 1494–1552). His work became so popular that many of the stunning and lyrical paintings produced in the Ming either copied or were in part inspired by his style—some of the works even bear a fake signature.

Traditionally attributed to Qiu Ying 仇英 (c. 1494–1552), calligrapher: Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470–1559), Journey to Shu (detail), Ming dynasty, 16th-17th century, ink and color on silk, blue-and-green style, China, 54.9 x 183.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — funds provided by the B.Y. Lam Foundation Fund, F1993.4)

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

Additional resources: