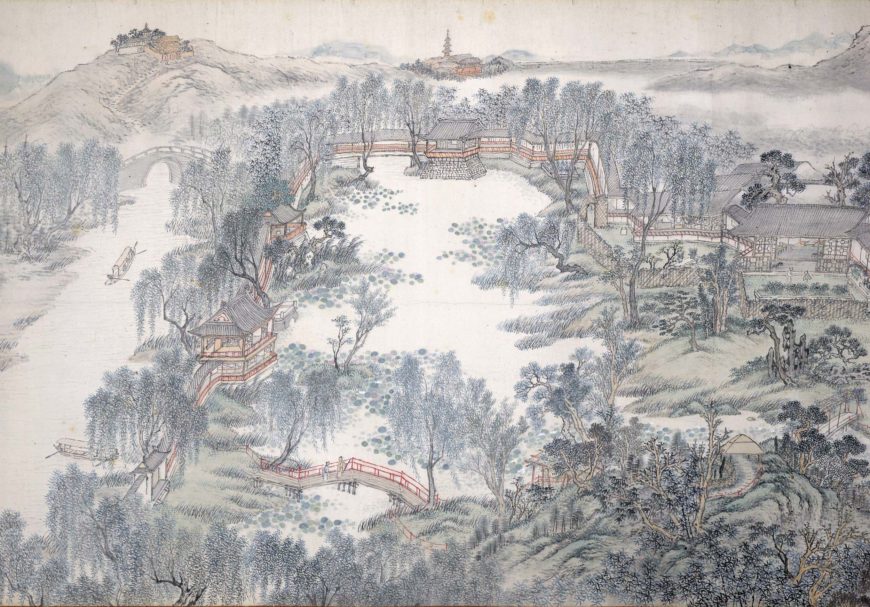

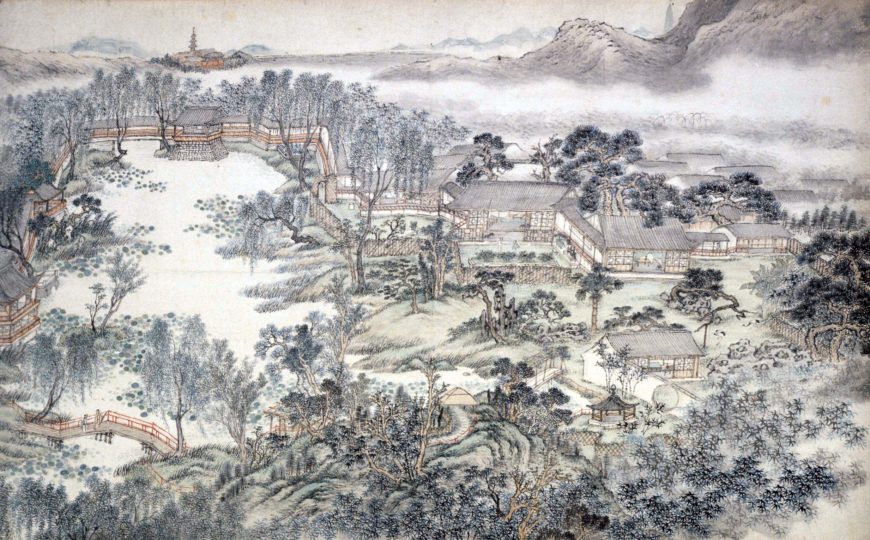

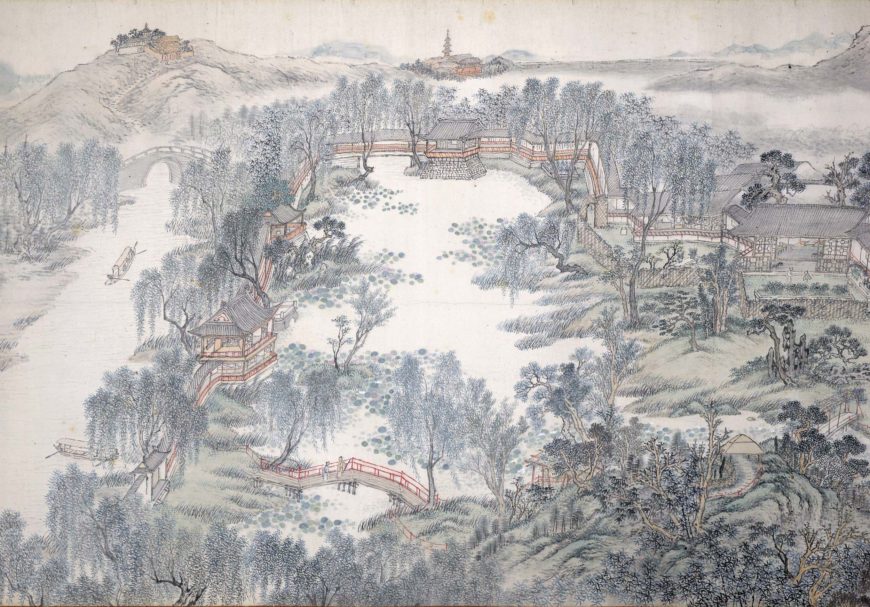

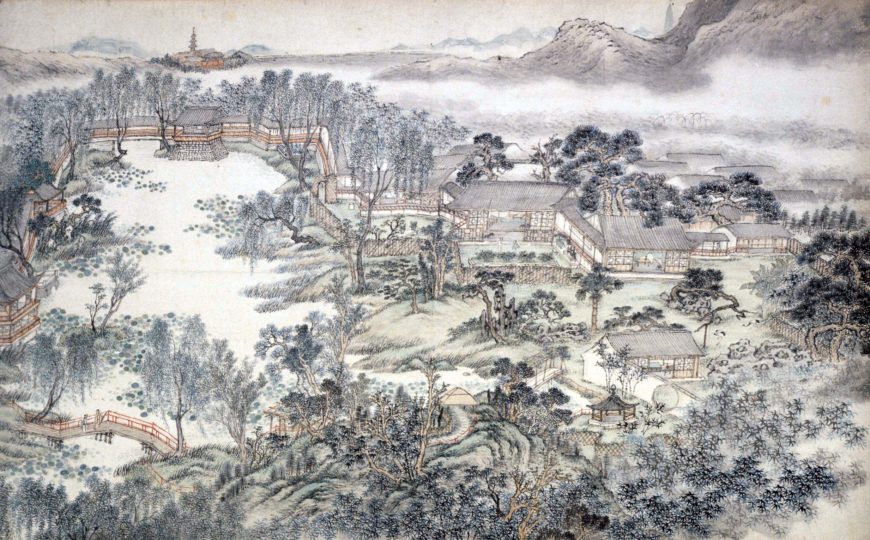

Tang Yifen 湯貽汾, Aiyuan tu 愛園圖 (Garden of Pleasure), handscroll, 1848, Qing dynasty, paint on paper, China, 59 x 160 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

South of the river

For hundreds of years the fertile area to the south of the River Yangtse has been associated with painters. In Chinese this region is called Jiangnan or ‘South of the River’. It includes such beautiful towns as Suzhou, Hangzhou and the Lake Tai area.

Here intellectuals and men of culture escaped or retired from political life in the capital to a life of leisurely, scholarly pursuits. Mostly wealthy and educated, the men would exchange paintings as gifts on special occasions or sometimes produce works together at poetry and painting parties, listening to music, and drinking wine in garden settings.

Gardens were an important part of life for these Chinese scholar-painters. They were seen as miniature landscapes and naturally eroded rocks were placed at the major viewing points among twisting and turning paths and streams. Each viewing point had its own name and perhaps a verse inscribed on the rock. The gardens of Suzhou were particularly famous during the Ming Dynasty.

Tang Yifen 湯貽汾, Aiyuan tu 愛園圖 (Garden of Pleasure), handscroll, 1848, Qing dynasty, paint on paper, China, 59 x 160 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

This painting by Tang Yifen is called The Garden of Delight. It depicts an ideal garden, painted in the orthodox style. There are twenty-six poems following the painting as well as many colophons or comments in praise of the garden.

Writing and seals on paintings

In China, men of culture were accomplished at poetry and calligraphy as well as painting, and writing often appeared on artworks. This sometimes describes how a painting was produced or for whom. It may also take the form of a comment by a later artist or collector, giving their view on its quality or significance. These comments, or colophons, usually appear at the beginning or end of handscrolls or sometimes down the sides of hanging scrolls.

Kuncan 髡殘, Landscape painting, ‘Autumn’ and ‘Winter’ leaves from a set representing the ‘Four Seasons’, showing mountains and buildings, with inscription, 1666, Qing dynasty, ink and color on paper, China, 35.1 x 894 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Artists and collectors also sometimes add their personal seal to scrolls, usually in red ink. Seal script, carved into the stone seal, is stylized and geometric and often difficult to decipher. Sometimes seals give the pen name of an artist or collector and some very famous paintings have many seals stamped on them, seemingly at random. Famous names can add to the value of a painting, by their association with it.

Autumn and Winter was painted by Kuncan (1612–73), a Chan (Zen) Buddhist monk who became abbot of a monastery near Nanjing. He wanted to use his painting to express personal experience rather than to represent a particular place and the writing on the two paintings has different functions.

The writing on the Autumn painting evokes an atmosphere:

My boat ever drifts among mists and waves, in a rock cave I hang my cloud gourd, not knowing the meaning of this, what man is it humming as he collects firewood?

On the Winter painting, Kuncan records how he came to paint the scene:

In the autumn of the year bingwu (1666), the great scholar Qingxi wasted time coming to see me in the hills and stayed for ten days. Quietly we conversed about Chan (Zen) ideas and the secrets of the Six Laws of painting…. Then you, Sir, produced four album leaves of paper from the Duanben Hall and asked me to paint them as I pleased. I have merely noted a little of the atmosphere and flavor, you should rap me on the head to teach me.

Copies and fakes

Traditionally, painters from China were expected to study the styles of earlier artists and as part of their training they learned by copying. However originality was also valued and a good artist was someone who studied the past, absorbed it and made it part of their original work. Scholar-painters from the educated class usually made it clear when their work recalled a painting by an earlier artist by adding titles and inscriptions.

Xiang Shengmo 項聖謨, Reading in the Autumn Forest 秋林讀書圖, 1623, Ming dynasty, ink and color on paper, 198.5 x 52 cm (©Trustees of the British Museum)

Here, Xiang Shengmo’s Reading in the Autumn Woods is compared with Wen Zhengming’s Wintry Trees. Shengmo’s work clearly shows the influence of Zhengming, particularly evident in the tall, narrow format showing a high mountain scene. In the foreground, a small figure in a house creates a sense of intimacy. Zhengming himself was also influenced by an earlier artist, Li Cheng (919–967), who is named in the inscription at top left of Wintry Trees.

Professional painters worked to order and so might make many copies of the same picture for their customers. Works by famous artists, especially from the past, were very valuable and this led to the production of fakes. Chinese writing on paintings tells many stories about fakes and forgeries, a subject of great interest to collectors. It can be difficult to distinguish between an ‘original’ painting copying an earlier style and a forgery.

Miniature mountains

Miniature mountain of bamboo root, carved to look like a rock, Qing Dynasty, 18th century, China, 24.8 x 30.4 cm (©Trustees of the British Museum)

Scholars often collected miniature mountains, carved out of different stones, to place on their desk. Mountains, because of their height, were seen as a bridge between earth and heaven. They were also linked with long life and immortality.

Small representations of mountains signified the retreat of the scholar from official life as well as a route to Paradise. They were rather like three-dimensional landscape painting and they brought the natural landscape into the study. Some were carved with hermits’ caves, reinforcing the idea of escape from the world into the beauty of nature. Brush rests were sometimes made in the shape of mountains. They had either three peaks or five, representing the Five Holy Mountains.

Rocks, representing miniature mountains, were also collected and placed where they could be admired, either in the study or in the garden. Some had been naturally eroded by water into strange shapes and were particularly admired and sought after.

© Trustees of the British Museum