Video from the Asian Art Museum.

Northwest corner tower of the Forbidden City and moat, Beijing, China (photo: A_peach, CC BY 2.0)

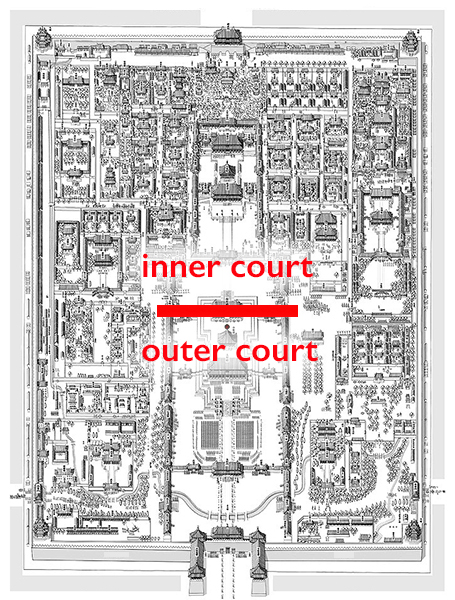

The Forbidden City is a large precinct of red walls and yellow glazed roof tiles located in the heart of China’s capital, Beijing. As its name suggests, the precinct is a micro-city in its own right. Measuring 961 meters in length and 753 meters in width, the Forbidden City is composed of more than 90 palace compounds including 98 buildings and surrounded by a moat as wide as 52 meters.

The Forbidden City was the political and ritual center of China for over 500 years. After its completion in 1420, the Forbidden City was home to 24 emperors, their families and servants during the Ming (1368–1644) and the Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. The last occupant (who was also the last emperor of imperial China), Puyi (1906–67), was expelled in 1925 when the precinct was transformed into the Palace Museum. Although it is no longer an imperial precinct, it remains one of the most important cultural heritage sites and the most visited museum in the People’s Republic of China, with an average of eighty thousand visitors every day.

Construction and layout

The construction of the Forbidden City was the result of a scandalous coup d’état plotted by Zhu Di, the fourth son of the Ming dynasty’s founder Zhu Yuanzhang, that made him the Chengzu emperor (his official title) in 1402. In order to solidify his power, the Chengzu emperor moved the capital, as well as his own army, from Nanjing in southeastern China to Beijing and began building a new heart of the empire, the Forbidden City.

The establishment of the Qing dynasty in 1644 did not lessen the Forbidden City’s pivotal status, as the Manchu imperial family continued to live and rule there. While no major change has been made since its completion, the precinct has undergone various renovations and minor constructions well into the twenty-first century. Since the Forbidden City is a ceremonial, ritual and living space, the architects who designed its layout followed the ideal cosmic order in Confucian ideology that had held Chinese social structure together for centuries. This layout ensured that all activities within this micro-city were conducted in the manner appropriate to the participants’ social and familial roles. All activities, such as imperial court ceremonies or life-cycle rituals, would take place in sophisticated palaces depending on the events’ characteristics. Similarly, the court determined the occupants of the Forbidden City strictly according to their positions in the imperial family.

The architectural style also reflects a sense of hierarchy. Each structure was designed in accordance with the Treatise on Architectural Methods or State Building Standards (Yingzao fashi), an eleventh-century manual that specified particular designs for buildings of different ranks in Chinese social structure.

View of the Meridian Gate from outside the Forbidden City (Imperial Palace Museum) (photo: Morio, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Public and private life

Public and domestic spheres are clearly divided in the Forbidden City. The southern half, or the outer court, contains spectacular palace compounds of supra-human scale. This outer court belonged to the realm of state affairs, and only men had access to its spaces. It included the emperor’s formal reception halls, places for religious rituals and state ceremonies, and also the Meridian Gate (Wumen) located at the south end of the central axis that served as the main entrance.

Looking to the Meridian Gate from the north (Imperial Palace Museum) (photo: inkelv112, CC BY-NC 2.0)

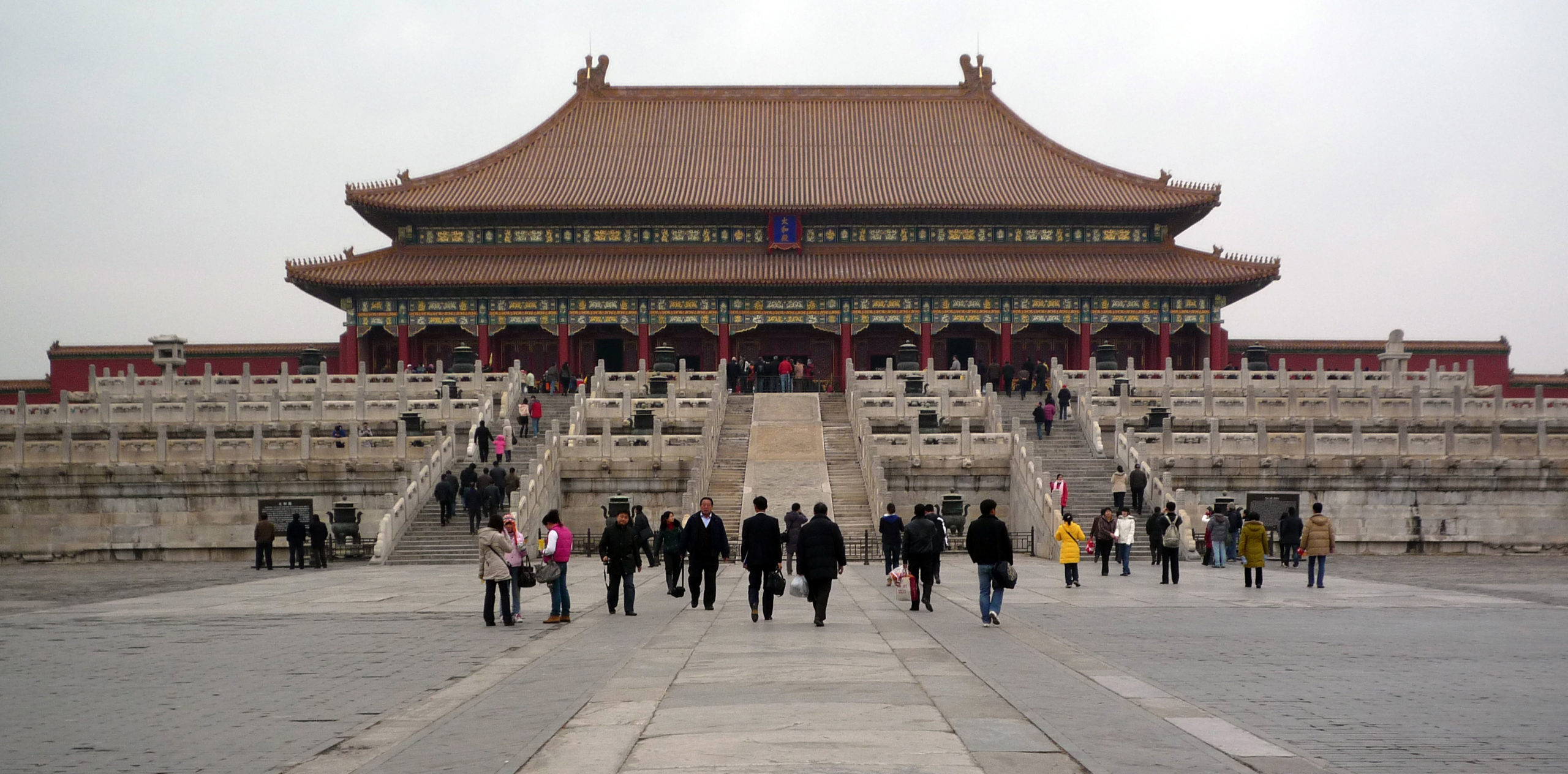

Upon passing the Meridian Gate, one immediately enters an immense courtyard paved with white marble stones in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihedian). Since the Ming dynasty, officials gathered in front of the Meridian Gate before 3 a.m., waiting for the emperor’s reception to start at 5 a.m.

View of the Hall of Supreme Harmony from the south (Imperial Palace Museum) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While the outer court is reserved for men, the inner court is the domestic space, dedicated to the imperial family. The inner court includes the palaces in the northern part of the Forbidden City. Here, three of the most important palaces align with the city’s central axis: the emperor’s residence known as the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqinggong) is located to the south while the empress’s residence, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunninggong), is to the north. The Hall of Celestial and Terrestrial Union (Jiaotaidian), a smaller square building for imperial weddings and familial ceremonies, is sandwiched in between.

Left: Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqinggong), Forbidden City, Beijing (photo: Xiquinho Silva, CC BY 2.0); Right: Hall of Celestial and Terrestrial Union (Jiaotaidian) and Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunninggong) (photo: R Boed, CC BY 2.0)

Although the Palace of Heavenly Purity was a grand palace building symbolizing the emperor’s supreme status, it was too large for conducting private activities comfortably. Therefore, after the early 18th century Qing emperor, Yongzheng, moved his residence to the smaller Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxindian) to the west of the main axis, the Palace of Heavenly Purity became a space for ceremonial use and all subsequent emperors resided in the Hall of Mental Cultivation.

Inner court showing the Palace of Heavenly Purity, the Hall of Celestial and Terrestrial Union, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility, and residences for the emperor’s consorts (map © Google Earth)

The residences of the emperor’s consorts flank the three major palaces in the inner court. Each side contains six identical, walled palace compounds, forming the shape of K’un “☷,” one of the eight trigrams of ancient Chinese philosophy. It is the symbol of mother and earth, and thus is a metaphor for the proper feminine roles the occupants of these palaces should play. Such architectural and philosophical symmetry, however, fundamentally changed when the empress dowager Cixi (1835–1908) renovated the Palace of Eternal Spring (Changchungong) and the Palace of Gathered Elegance (Chuxiugong) in the west part of the inner court for her fortieth and fiftieth birthday in 1874 and 1884, respectively. The renovation transformed the original layout of six palace compounds into four, thereby breaking the shape of the symbolic trigram and implying the loosened control of Chinese patriarchal authority at the time.

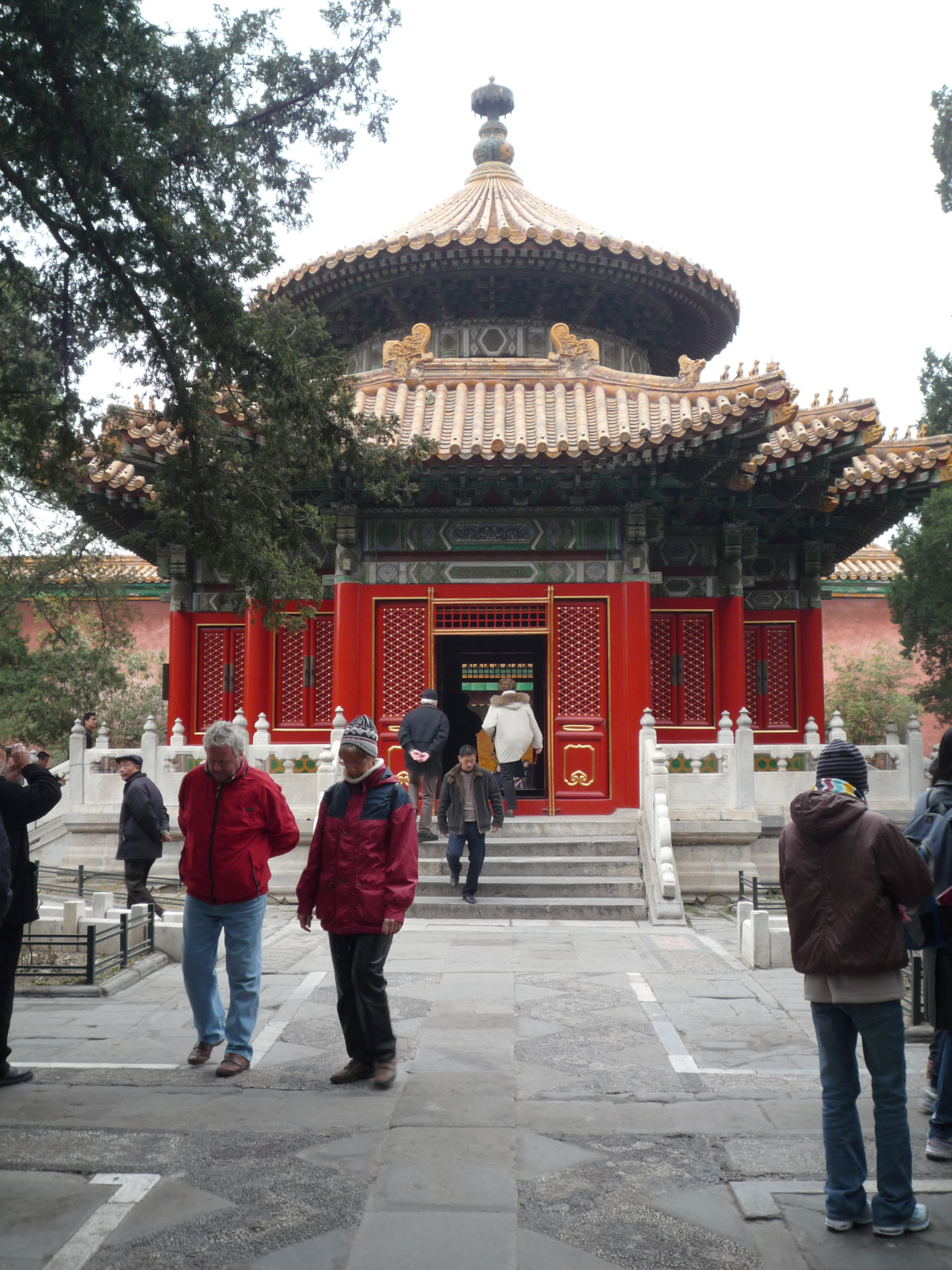

Temple, Forbidden City, Beijing (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The eastern and western sides of the inner court were reserved for the retired emperor and empress dowager. The emperor Qianlong (r. 1735–96) built his post-retirement palace, the Hall of Pleasant Longevity (Leshoutang), in the northeast corner of the Forbidden City. It was the last major construction in the imperial precinct. In addition to these palace compounds for the older generation, there are also structures for the imperial family’s religious activities in the east and west sides of the inner court, such as Buddhist and Daoist temples built during the Ming dynasty. The Manchus preserved most of these structures but also added spaces for their own shamanic beliefs.

The Forbidden City now

Today, the Forbidden City is still changing. As a modern museum and an historical site, the museum strikes a balance by maintaining the structures and restoring the interiors of the palace compounds, and in certain instances transforming minor palace buildings and hallways into exhibition galleries for the exquisite artwork of the imperial collections. For many, the Forbidden City is a time capsule for China’s past and an educational institute for the public to learn and appreciate the history and beauty of this ancient culture.

Additional resources: