Peoples and cultures of Africa: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 63

The arts of Africa, c. 18th–20th century

Headdress: Male Antelope (Ci Wara), 19th–20th century Mali, Segou region, Bamana, wood, metal bands, 71.1 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Traditional African art, which generally refers to tangible forms and practices that were created by Africans for Africans, played a central role in the communities where it was created. The late African art historian Robert Farris Thompson has argued that art in Africa is used to make things happen. For example, the performance of the Ci Wara antelope mask inspires farmers and reminds viewers of the importance of community. African art can communicate royalty, sacrality, aesthetic interests, genealogy, morality, popular trends, and other significant concerns. It is also efficacious and necessary for events like rituals, masquerades, and life-cycle transitions to successfully occur.

Google earth view of Africa (© Google)

Africa is a large and wildly diverse continent with vast differences in climate, geography, flora and fauna, and cultures. There exist over 1,000 ethnic groups with distinct languages, belief systems, and artistic traditions. In the early 1800s, following the end of the transatlantic slave trade, European interest turned to Africa’s natural resources, particularly mineral wealth and forests. This led to colonization from roughly 1880–1914. In some cases, art created during this time period was a means of making sense of this time marked which was by violence and coercion. This period was followed by struggles for liberation from colonial rule in the mid-20th century and art began to express a nationalist identity and the ideologies of the postcolonial state—ideologies that focused on self-governance and nation building, economic development, and cultural identity after European imperialism.

In this installation, Yinka Shonibare MBE has repositioned the European men who divided the African continent as brown-skinned, wax-print wearing figures gesturing to a map of Africa. The heads of state appear headless—mindless and senseless like the act they are committing. Their wax print coats, a fabric once manufactured in Holland using Indonesian techniques and traded in West Africa, and their skin tone suggest mixed race, thereby subverting the imperial narrative and reminding the viewer of the complex nature of the “scramble for Africa” in the late 1800s. Yinka Shonibare MBE, Scramble for Africa, 2003, 14 life-size fiberglass mannequins, 14 chairs, table, Dutch wax printed cotton (The Pinnell Collection, Dallas) © Yinka Shonibare MBE

Africa today is divided into 53 independent countries but the boundaries that separate these countries were drawn by 13 European powers at the Berlin Conference in 1884–85 without a single African present. They did not divide the continent along cultural lines but based these borders on European interests. The problems this created—separating families, language groups, trading partners, pastoralists from watering holes, etc.—are still felt throughout the continent today.

This chapter begins by considering the importance of seeing art in its cultural context and explores how museum displays have shaped the Western understanding of African art. It then explores African artworks that communicate social status, evoke memory and secrecy, help individuals interact with the spiritual realm, and move though specific life-cycle stages.

Read an introductory essay

/1 Completed

African Art and Cultural Context

Ci wara kun (Male and Female Antelope Headdresses), 19th–20th century, Bamana peoples, wood, 90.7 x 40 x 8.5 cm, Segou region, Mali (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When European travelers first reached the coast of West Africa in the 15th century, they found a whole host of new objects and practices that they were unfamiliar with and often misinterpreted. As an Ewe proverb states, “The strangers eyes are wide, but they are blind.” To begin to really “see” African art, we start with the premise that all art communicates. Understanding how it communicates and what it says is the role of the art historian and requires an understanding of the art’s cultural context. This is particularly important for works of art that may not be familiar to us.

Photograph of an Oromo woman from Ethiopia (photo: Peri Klemm)

As an example, what conclusions might someone outside of Ethiopia draw regarding this woman in the photograph above?

If you grew up in or are familiar with Oromo culture, just looking at this woman’s dress you might be able to determine the wearers’ approximate age, her economic background or that of her family, her religion, her political affiliation, and her regional identity. But if you weren’t familiar with her culture, what would you know about this woman based on her dress? Without speaking to her, little is communicated to those not familiar with Oromo culture. It is therefore critical to study cultural context to make sense of African art.

Ceremonial Palm Wine Vessel, 19th–20th century, Grassfields region, Cameroon, gourd, glass beads, cloth, cane, wood, 76.2 x 30.8 x 19.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Studying African art outside of Africa can be challenging for at least three reasons. When you visit a museum in the West to see African art, you often find objects hanging on a wall or placed behind glass cases. Most African art discussed in this chapter, however, was made to be used, whether in a sacred or a secular context, and communicated a whole host of information. It is important to consider why and how artworks were meaningful to the communities where they were created and used—as well as how the objects got into the museum in the first place. All of the artworks in this chapter are located in Western museums.

We also have to keep in mind that we often don’t have input from the artist who made the work. Most art historians think of African art as a dialogue, a mode of communication between the audience, the artist/culture, and the object. Without information on the artist and their concerns, we are missing part of that conversation and this can make a sound analysis difficult.

Further, how the material and expressive cultures of Africa have been studied and portrayed by non-Africans requires critical awareness, such as this statement below from the British Museum notes.

Who defines African art?

As far as culture and art is concerned, “African” so often seems to be defined by people who are not African, including museum curators and art historians who identify themselves and their own cultural heritage as unambiguously European. This includes people from far beyond Europe, and some of the finest collections, publications and scholars of African art are to be found in North America. Peoples and cultures do indeed travel, and many African art schools share a Western cultural and artistic tradition which traces its origins to Europe or the Middle East. Africa is a diverse continent of many cultures, but one experience shared by the vast majority of its people and emigrants, is life under political and economic systems developed by Europeans and still dominated by them.

This excerpt from the British Museum, a largely white institution embroiled in a debate about restitution and repatriation of their African holdings, demonstrates how African art and culture has been historically understood within art historical scholarship and the EuroAmerican popular imagination.

Ibeji Twin Figure, 19th–20th century, Nigeria, Yoruba peoples, wood, beads, cam wood powder, pigment, 9 1/4 x 3 9/16 inches (23.5 x 9 cm)

It is our job to learn as much as we can about the cultural contexts of objects. Two common characteristics of African objects are useful for us to consider when looking at the art discussed in this chapter:

- the connection between cultural values and how an object looks (aesthetics)

- the abstract and idealized style of many of the objects of this time period

The importance of these two key issues is clearly illustrated in the sculpture of twins known as Ire Ibeji, made by the Yoruba in present day Nigeria. The Ire Ibeji twin figures visually communicate key ideals in Yoruba society: the emphasis on the head (the site of wisdom), the depiction of the prime of life (ideal time in life), and the need to remember and honor the deceased.

Read essays and watch a video about African art and its cultural context

The Reception of African Art in the West: Learn more about how African art and culture has been historically understood within art scholarship and the EuroAmerican popular imagination.

Read Now >

Aesthetics: Objects created by African artists often express, aesthetic, functional, and moral values all at once.

Read Now >

Form and meaning: Many forms of African art are characterized by visual abstraction or departure from representational accuracy.

Read Now >

Ere ibeji carvings: These reveal not only the importance of twins and a strong belief in the afterlife, but what Yoruba regard as beautiful and correct.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Art and Social Status

Throughout Africa, art can communicate the social status of individuals and groups. While the examples discussed here, from Ghana and Nigeria, don’t literally speak, those who understand their aesthetic language know their meaning.

Asante art in Ghana

Map with the Asante region indicated in green

To examine the role of art in communicating an individual or group’s identity, we begin in West Africa among the Asante in Ghana. Prior to independence in 1957, Ghana was a British colony in West Africa, known as the Gold Coast. Ghana is the second largest producer of gold in West Africa, and European powers took an interest in Ghana for the monetary value of its gold.

Asantehene Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu II, Kumasi, Ghana, in 2017. Notice the gold adornments, large sandals, and kente cloth. A large parasol is above him (not visible here); we can see someone on the right holding the base of the parasol (photo: Alfred Weidinger, CC BY 2.0)

For the Asante, one of more than 70 ethnic groups in Ghana, gold was a symbol of aristocracy. The Asante are a kingship with the palace and capital in Kumasi. The Asante, part of a larger linguistic family known as the Akan, rose to power as a nation in the early eighteenth century when a chief named Osei Tutu united a vast series of principalities under one throne. The Asante nation was strengthened through its control of the trade in gold, textiles, and enslaved people. This wealth allowed artistic traditions, especially those for royal patrons, to flourish. The king, or paramount chief, is called the Asantehene in the Twi language. The Asantehene remains an important patron of the arts today.

Asante dancer in kente cloth tapping fists, 2017, at the University of Ghana (photo: Peri Klemm)

During funerals in Ghana, an Asante dancer taps his fists together in a vertical motion to signify the glory of the Asantehene, who is believed to symbolically bridge heaven and earth. This notion is further enhanced by the Asantehene’s dress. He is visually sandwiched between bulky sandals decorated with gold ornaments and a large, multi-colored umbrella overhead.

Otumfuo Opuko Ware II, Asantehene, surrounded by men and women of royal stature, Asante peoples, Ghana (photo: © Frank Fournier, 1995)

Asante men and women of royal stature wear gold threads, gold filigree beads, and gold dust sprinkled on the face. Here, gold shows the royal status of the wearer and the opulence of the palace through the decoration of household objects such as sword hilts, fly whisks, and linguist staffs.

Wooden stool ornamented with silver, Asante people, Ghana, 19th century (Trustees of the British Museum)

Stools have a special significance in Asante culture. Those made by carvers and given to young men and women around puberty by their parents have at their center particular patterns that represent proverbs. These stools are cherished and used for everyday activities including eating, socializing and playing games.

Sika dwa kofi (Golden Stool), always displayed on its side, Asante people (Ghana), c. 1700 and Asante weights (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

The stools tipped on their side are the stools of past chiefs and housed in the stool room of the Asante palace in Kumasi. The Golden Stool, on the other hand, is considered the most sacred relic of the Asante nation and is never actually used as a seat. It is a wooden stool covered in gold leaf.

Asante brass weights. Left: Weight in the shape of a figure, 1950–60 (Asante, Ghana), brass, 6.8 cm high (Cleveland Museum of Art); right: Weight in the shape of a fish, 1800s (Asante, Ghana), brass, 2.8 x 6.6 x 0.4 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art)

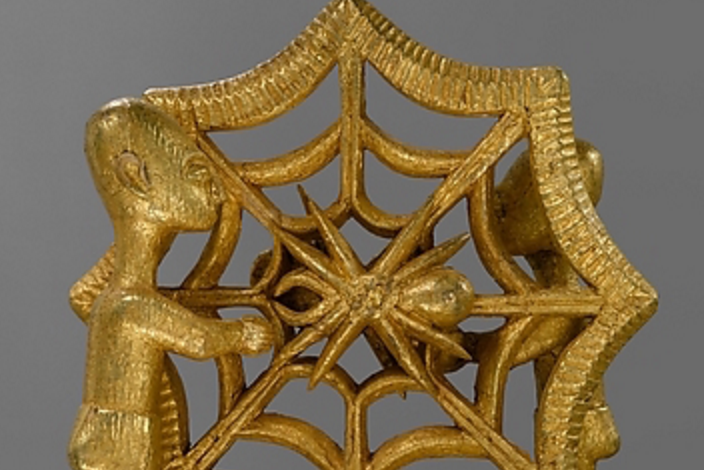

To help us make sense of the importance of gold for the Asante and the Golden Stool, we can also turn to brass weights. These weights, used during the gold trade by the Asante since the 14th century, were first created by goldsmiths as standard measurements to weigh gold. Gradually these brass bars were fashioned into hundreds of fanciful images that connected to verbal sayings. Some of the weights show recognizable forms; others are a system of patterns. Scholars believe these may have developed into a written language system over time if it were not for the disruption of the slave trade and colonization.

Left: Asante linguist holding his staff; right: linguist (Okyeame) staff, 20th century, wood and gold leaf, Ghana, Central Region, 159.4 x 17.8 x 9 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Important members of the Asantehene’s court are his linguists. These men are oral historians, orators, politicians, language specialists, and advisors. At many public occasions, however, the linguist does not talk at all but lets a staff speak for him.

Linguist staff (okyeame poma), 1st half of the 20th century, Asante peoples, Ghana, wood and gold leaf, 1 m 60.02 cm x 25.083 cm x 20.32 cm (Dallas Museum of Art)

These wooden staffs are covered in gold and topped with a carving, representing an Asante proverb: “One who climbs a good tree, gets a push,” meaning right intention and action receive support.

Kente weaver in Adanwomase village, Ashanti Region, Ghana (video: Shawn Zamechek, CC BY 2.0)

Another art form that is associated with royalty is Kente cloth. Kente is a strip-woven cloth woven on a loom by male weavers. It was traditionally the cloth of royalty with new patterns and proverbs created for each Asantehene and his family. Today, the cloth has become “democratized” and commodified. This means that anyone who can afford it may wear it.

Watch videos and read essays about Art and Social Status

Golden Stool (Sika dwa kofi), Asante peoples: In this video you’ll learn more about the Asante Golden Stool through a closer look at brass weights that were used to weigh gold.

Read Now >

Linguist Staff (Okyeamepoma) (Asante peoples): This magnificent gold-covered staff was created to serve as an insignia of office for an ȯkyeame, a high-ranking advisor to an Asante ruler.

Read Now >

Kente cloth: This cloth—first woven by a wise spider—sends social messages through a system of specific patterns.

Read Now >

Paa Joe, Coffin in the Form of a Nike Sneaker: This elaborate coffin, modeled after a Nike Air sneaker, communicates the wealth and interests of the patron.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Royal and personal art in Nigeria

In neighboring Nigeria, royal status is communicated in palace architecture. For example, in a veranda post made by the well-known sculptor Olowe of Ise, a male figure on horseback is supported by a kneeling female figure.

Olowe of Ise, Veranda post, before 1938 (Yoruba people, Nigeria), wood, pigment, 180.3 x 28.6 x 35.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City)

Olowe of Ise represented the figures with large heads, protruding almond shaped eyes, and breasts. These forms all related to the leadership qualities of the king to provide for his community. This post would have held up the porch of the palace. Olowe of Ise is Yoruba, and his figures stylistically resemble the Yoruba Ere Ibeji twin figures mentioned earlier. With their idealized heads, eyes, and breasts, neither resembles an exact likeness of a human face or body.

Ikenga, Igbo peoples, Nigeria, wood (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

Besides art that marks royal status, we can look at art, such as a figure known as an “ikenga” from the Igbo in Nigeria, to consider a more personal marker of status. This figure represents the achievements of a title holder of high rank. It suggests an individual’s mastery in his discipline and perseverance in achieving his title.

Watch videos and read essays about royal and personal art in Nigeria

Olowe of Ise, veranda post (Yoruba peoples): This equestrian king is clearly powerful, but he rests on a nude female figure from whom his power is derived.

Read Now >

Ikenga (Igbo peoples): These carved wooden figures have human faces but animal attributes, and reflected the achievements of their owners.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Masquerade

Female (pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of Congo, early 20th century, wood, plant fiber, pigment, copper alloy, 39.1 cm high (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art)

In West and Central Africa where hardwood forests grow, we find many cultures that created and utilized carved wooden masks and some continue the practice today. For most of these cultures, a mask is not only a structure or costume that conceals the face and body but an idea and an action. The idea behind masking is for the person wearing and performing the mask to conceal his or her identity and take on a new one. Sometimes the masker “becomes” an ancestor, a spirit, or a supernatural animal.

Elephant (Aka) Mask, Kuosi Society, Bamileke Peoples, Grassfields region of Cameroon, 20th century, cloth, beads, raffia, fiber, 146.7 x 52.1 x 29.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Unlike the idea of masking at Halloween or Carnival, a masquerade requires more than just a facial cover—it involves a costume, an ensemble of actors, and a performance. A masquerade usually includes: a wooden mask, raffia or cloth costume, mask attendants, dancers, musicians, a performer, and often a spirit who animates the male or female performer/wearer. Masks are used throughout Africa at many different occasions, like life cycle ceremonies, religious events, and political rallies. They can instruct, discipline, warn, honor, and entertain.

Watch videos and ready essays about masks

Male and Female Antelope Headdresses (Ci wara) (Bamana peoples): These headdresses celebrate the divine Ci Wara, half man and half antelope, who introduced humans to agriculture.

Read Now >

Female (pwo) Mask: This mask was made and worn by men, but its purpose is to honor women who have bravely survived childbirth.

Read Now >

Owie Kimou, Portrait Mask (Mblo) of Moya Yanso (Baule peoples): This mask is a portrait of a particular woman, but was worn and danced by her male relatives.

Read Now >

Elephant Mask (Bamileke Peoples): The austere display of this powerful object masks the complexity of its original context.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Initiation and art as life cycle markers

Masking during Initiation

Masquerades can also help an individual navigate the physical transformations of life. As a person moves from childhood to adolescence to old age, African societies often mark these transitions through life-cycle rituals that involve masquerades. Some of the most important rituals happen during puberty when initiates may be taken away from their families and educated by older, wiser men or women about how to be good parents, spouses, and society members and how to take care of their families. They may also be taught history, genealogy, farming, medicine, and sacred knowledge. (Think of how youth around the world might benefit from such a class!)

Sande

Young women who live in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia practice an exclusively female initiation ceremony called Sande. It is a complementary social organization to the young men’s Poro society where men learn farming, hunting, tribal history, and secret knowledge. Sande is comparable to female initiation in other regions of Africa, yet it is unique in that it is the only society where women completely cover their bodies in a black costume and wear a mask in performance.

Bundu or Sowei Helmet Mask (Ndoli Jowei), Mende, Nguabu Master (Moyamba district, Sierra Leone), late 19th-early 20th century, wood and pigment, 39.4 x 23.5 x 26 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

The Sande mask is called Sowei and it is worn and danced by an older woman to instruct young female initiates while in seclusion outside the village. It represents the ideal beauty of a Sande woman with a high broad forehead, small facial features, a hairstyle composed of tufts and braids, neck creases, and a shiny black finish. The Sowei mask is used to initiate Mende girls into the Sande society and to oversee their rite of passage to adulthood.

Watch a video and read an essay about a Sande mask

Bundu / Sowei Helmet Mask (Mende peoples): The Mende initiation rite for young women is the only known masquerade tradition where the mask-wearers are female.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Ndebele art in the lifecycle

For Ndebele women, beadwork plays an important marker of one’s stage in life and is a way for women to show off their artistic talents, decorate themselves and their daughters, and communicate their positions in society through their dress and materials. Beadwork, such as we see on an ijocolo, began to flourish under incredibly difficult circumstances.

Marriage apron (itjogolo or ijogolo), 1920–40, Mpumwanga, South Africa, leather, glass beads, fabric (Newark Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Ndebele were semi-nomadic herders until the 1870s when they ran into conflict with the Afrikaner population, also known as the Boers—those of Dutch descent who had settled in southern Africa as farmers. The Afrikaners were either demanding land from the Ndebele or requiring that they pay taxes on land use. The Ndebele initially refused. By 1882, the Afrikaners cut off the Ndebele supply to food, burned their villages and killed many of their herds until they surrendered. Those that still refused were made indentured laborers for five years, creating tremendous upheaval.

In 1923, the government allowed the Ndebele to purchase limited farmlands but no other provisions. While the Ndebele had been used to living on their ancestral grazing land, they were now limited to faraway farmland. By 1975, under the apartheid regime, the KwaNdebele homeland was established by the government as a place for the Ndebele to reside. It was very far from their indigenous home.

Bright colors and bold patterns adorn the house and clothing of this South African woman from the Ndebele tribe. Photo from January 1, 1983 (UN Photo,CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The government promised to provide running water and electricity and a factory so the Ndebele could earn a living. They received none of these things. Yet, beadwork and muralwork began to flourish. Why would art flourish at a time when the Ndebele could scarcely access the basic necessities to live?

During this time of forced racial segregation, one of the most popular symbols painted on walls and beaded into unmarried girl’s skirts was lights. One Ndebele painter was asked why she had painted abstract lights in the form of triangles on the mud walls of her compound. She replied “I give my home lights as it has no lights.”

Ndebele apron with imagery of lights, 20th century

Images of modernity like electricity provided Ndebele women access to the things they were promised but never received. In this sense, the depiction of electricity was seen as an empowering way to claim modern amenities, at least symbolically, during the harsh rule under the apartheid system.

Apron (Isephephetu), Ndzundza Ndebele, c. 1960, cloth, beads, fiber, South Africa, 33.7 x 43.2 x 1 cm (Michael C. Carlos Museum)

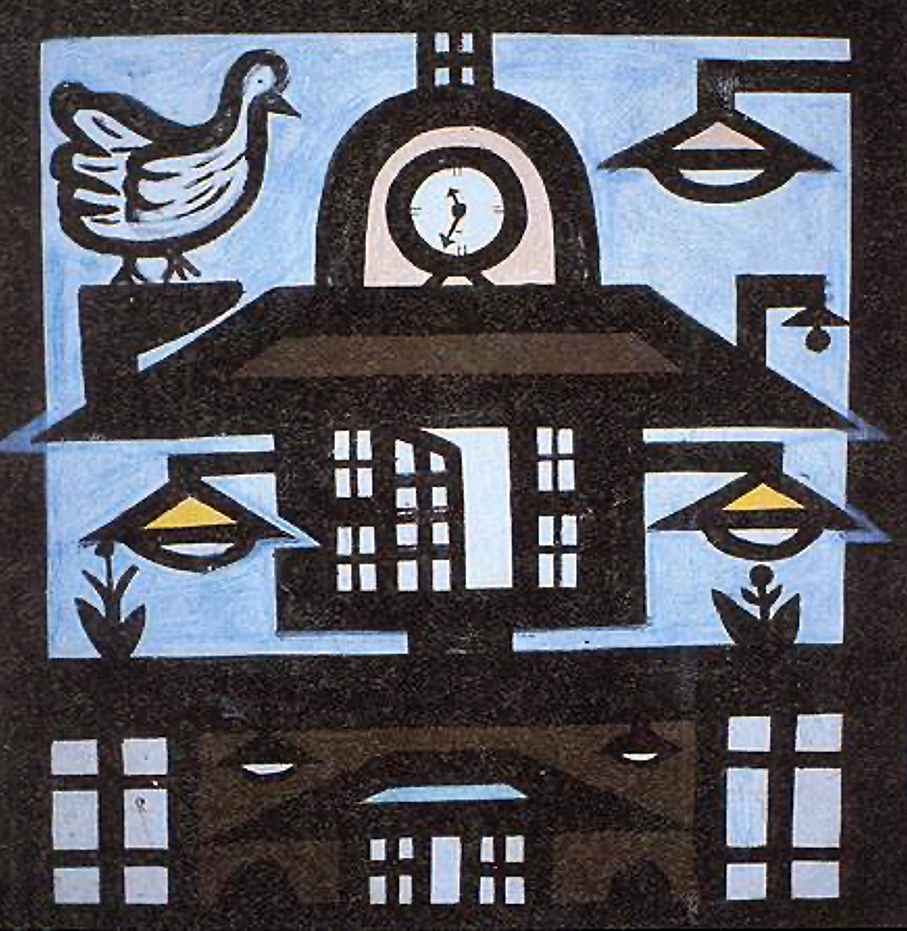

A girl’s apron (isephephetu) is beaded by her mother and gifted when she completes her initiation. The images, like lights, houses, and airplanes, demonstrates her mother’s hopes and dreams for her daughter even under the oppressive apartheid regime.

After marriage, the woman adopts an ijocolo, an apron she beads herself. She is no longer beading her dreams but rather she depicts what she has and what she’s proud of. In one example, the artist has beaded a view of her compound, a place that she built and presides over. A typical compound is made of mud, white washed and painted with murals and holds sleeping quarters, a kitchen, corrals for animals, and a common area.

Watch a video and read an essay about an ijocolo

Married Woman’s Apron (itjogolo or ijogolo), Ndebele peoples: These decorated aprons were gifts from the groom’s family to his wife, and signified her new role in society.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Secrecy, Security, and Memory

The power of many artworks comes from their perceived ability to protect or guard an individual and to jog a memory or memorialize an individual. While museum displays usually privilege the visual and visible, for some African objects, what is not seen is often the most powerful or significant. That which is concealed, like the inside of an amulet, evokes mystery.

Amulets, Ethiopia (photo: Peri Klemm)

Throughout the Horn of Africa and North Africa, the most potent objects are often located centrally on the body, yet concealed. The power of the amulet comes from the fact that its casing is visible at the neck but its contents are hidden. The viewer is not privy to the particular amuletic abilities inside the leather case and therefore, must keep himself/herself on guard.

In Ethiopia, amulets made of square leather cases are used by a number of different ethnic groups, including the Argobba, the Oromo, the Amhara, and the Tigrean and are worn around the neck by Muslims, Christians, and traditional practitioners alike. In Ethiopia, like in many regions of North Africa, amulets play a major role in protecting their wearers from the evil eye. Those that possess the ability to inflict harm through the gaze are known by the Amharic term buda. Historically, buda referred to an artisan class who engaged full-time in metalsmithing, tanning, or pottery. Buda are regarded with suspicion because they usually do not own land, they do not work the land as farmers, and they do not participate in animal husbandry.

Left: A leather case for an amulet; right: a toddler in Ethiopia wears a paper amulet (photos: Peri Klemm)

An amulet tied on a piece of string is often the first adornment that a newborn receives. In later childhood, amulets may be tied around the neck when someone enters the marketplace, a place fraught with strangers. Young women are thought to be more susceptible to the attention of buda because their youth and their use of beauty aids (like perfumes, nail polish, and an array of jewelry) make them excessively beautiful and cause jealousy in those with the evil eye.

Among the Muslim Argobba, stitched leather pouches filled with Qur’anic formulas written on parchment are designed to arrest destructive supernatural power by reflecting the evil eye of foreigners, metal workers, or evil spirits. Among the Christian Amhara, leather cases filled with medicinal herbs and made for them by low class priests of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, are used in order to ward off the gaze of buda.

Egungun masker (photo: Derek B)

In a similar sense, some art forms also conceal powerful substances or medicines. Among the Yoruba, a cloth masquerade called Egungun, for example, has a medicine bundle tied up under its folds that activates the spirits of ancestors when it is danced. This bundle would be removed before an Egungun costume would be sold or traded.

Power Figure: Male (Nkisi), 19th–mid-20th century, Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, wood, pigment, nails, cloth, beads, shells, arrows, leather, nuts, twine, 58.8 x 26 x 25.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Kongo diviners used figurative sculptures called Nkisi to act as supernatural witnesses, judges, and vindicators. Sacred unseen substances placed in a cavity in the abdomen functioned as the activating and animating materials of the sculpture’s spirit.

Watch videos and read essays about secrecy, security, and memory

Power Figure (Nkisi Nkondi), Kongo peoples: Nkisi nkondi figures are highly recognizable through an accumulation of pegs, blades, nails or other sharp objects inserted into its surface.

Read Now >

Male Reliquary Guardian Figure (Fang peoples): These figures look calm and contemplative, but also display real strength and vitality in their muscular forms.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Remembering

Many cultures in Africa also employ objects to remember and interpret the past. With limited writing systems on the continent prior to colonial rule, objects could act as historical documents used by oral historians. Just as history books present a particular perspective, oral interpretations should also be thought of as fluid and dynamic.

Lukasa (memory board), Mbudye Society, Luba peoples (Democratic Republic of Congo, c. 19th to 20th century, wood, beads and metal

In the Luba Kingdom of the Democratic Republic of Congo, oral historians and diviners touch a memory board called “lukasa” to help them recount the history of the royal lineage. History was traditionally performed—not read.

Ndop Portrait of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul, c. 1760–80, wood and camwood powder, 19-1/2 x 7-5/8 x 8-5/8″ (Brooklyn Museum)

Among the Kuba in the Democratic Republic of Congo we have an actual portrait sculpted some time after the king’s reign in the late 18th century. This figure, called an ndop, depicts king Mishe miShyaang maMbul with the specific pattern and drum affiliated with his rule. This memorialization of the king was used by court historians to interpret events from the past associated with his rule.

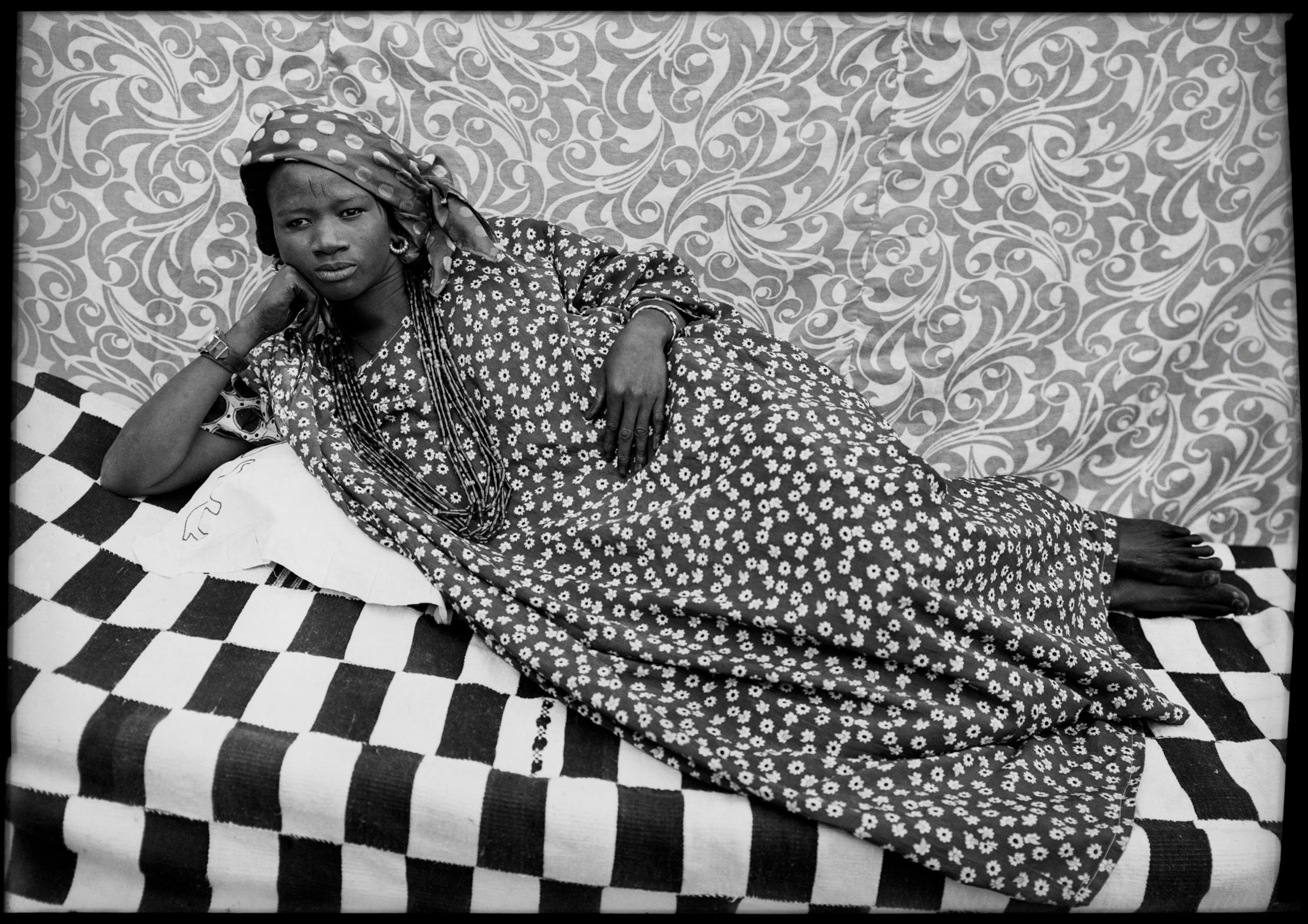

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1956–57, gelatin silver print, 39.1 x 55.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A more modern means of memorialization is the photograph, a form of portraiture that became popular in urban centers throughout Africa by the mid-twentieth century. The photographer, Seydou Keita for instance, created black and white images of the middle class in his portrait photography studio in Bamako Mali.

Watch videos and read essays about remebering

Lukasa (Memory Board) (Luba peoples): Long before the advent of cell phones and social media, the Luba had invented their own handheld memory device.

Read Now >

Ndop Portrait of King Mishe miShyaang maMbul (Kuba peoples): The king did not sit for this portrait; in fact, the artist carved it without directly observing his subject.

Read Now >![Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/screen-shot-2016-10-15-at-8-42-48-am.png)

Seydou Keïta, Untitled (Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress): Studio photography produced mementos for the growing middle class: Keïta’s Bamako studio was abuzz with clients.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The colonial period had a profound effect on the arts of Africa. With the introduction of Christianity and the further spread of Islam in the nineteenth and twentieth century, many traditional art practices associated with indigenous religion declined. Also, as new trade items entered the local economy, handmade objects like ceramic vessels and fiber baskets were replaced by commercial containers. As African artists began catering to a new market of middle-class urban Africans and foreigners, many new art-making practices took their place. Self-taught and academically trained painters, for example, began depicting their experiences with colonialism and independence. As fine artists, their work is largely secular in content and meant to be displayed in galleries or modern homes. Today, many contemporary artists are influenced by tradition-based African art forms just as European avant-garde artists like Pablo Picasso, André Derain, and Georges Braque looked to abstract African sculpture as a source of inspiration for their artwork in the late 1880s.

While this chapter explored some key themes in traditional African art, there are endless expressive art forms, rich in meaning and historical depth, to learn about.

Key questions to guide your reading

Discuss the ways that an African art object communicates. What does a particular work of art say? Who is the intended audience?

How does African art communicate information to the viewer in a non-verbal manner? How can people communicate information over long distances and through many generations without written records?

What are the relationships between art and social status, art and initiation, and art and memory?

Jump down to Terms to KnowDiscuss the ways that an African art object communicates. What does a particular work of art say? Who is the intended audience?

How does African art communicate information to the viewer in a non-verbal manner? How can people communicate information over long distances and through many generations without written records?

What are the relationships between art and social status, art and initiation, and art and memory?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Apartheid

Asantehene

Berlin Conference

Golden Stool

Ijocolo

Isephephetu

Kente cloth

Linguist staff

Lukasa

Masquerade

Nkisi Nkondi

Poro Society

Learn more

Watch a video of a Bwa Hawk masquerade