Owie Kimou, Portrait Mask (Mblo) of Moya Yanso, Baule peoples (Côte d’Ivoire), early 20th century, wood, brass, pigment, 36.2 cm high (private collection; photo: Sotheby’s)

The 400,000 Baule who live in central Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa have a rich carving tradition. Many sculpted figures and masks of human form are utilized in personal shrines and in masquerade performances. This mask was part of a secular masquerade in the village of Kami in the early 1900s.

Masquerade

The Baule recognize two types of entertainment masks, Goli and Mblo. To perform a Mblo mask, like the one depicted, a masker in a cloth costume conceals his face with a small, wooden mask and dances for an audience accompanied by drummers, singers, dancers, and orators in a series of skits. In the village of Kami, the Mblo parodies and dances are referred to as Gbagba. When not in use, the Gbagba masks were kept out of sight so it is unusual that we get to see a mask displayed in this manner.

To the Baule, sculpture serves many functions and these can shift over time and within different contexts. The Gbagba masquerade is a form of entertainment no longer practiced in Kami since the 1980s, replaced today by newer masks and performance styles. What is known, however, is that masks like this one were not intended to be hung on a wall and appreciated, first and foremost, for their physical characteristics. Sculpture throughout West Africa has the power to act; to make things happen. A carving of a figure, for example, can be utilized by practitioners to communicate with ancestors and spirits. The physical presence of a mask can allow the invisible world to interact with and influence the visible world of humans. Scholar Susan Vogel mentions that Gbagba could bring social relief at the end of a long day and respite from everyday chores. It allowed residents to socialize, mourn, celebrate, feast, and even, court. [1]

Moya Yanso

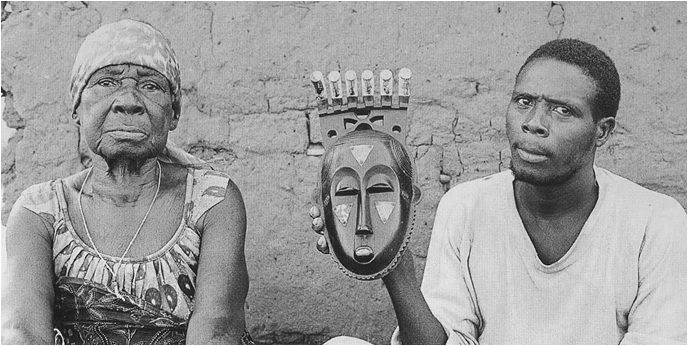

In the case of this Gbagba mask, Vogel tells us that it was meant to honor a respected member of Baule society. This mask is unusual. Most older African carving come into Western collections without information about the artist or subject, but in this case, both the carver and the sitter have been recorded. In the photograph below we see an older woman seated next to the portrait mask. She is Moya Yanso and this is her image carved by a well-known Baule artist, Owie Kimou. The man holding the mask is her stepson who danced this mask in a Gbagba performance. It was commissioned and originally worn by Kouame Ziarey, Moya Yanso’s husband and later his sons. Revered as a great dancer, Moya Yanso accompanied the mask in performances throughout her adult life until she was no longer physically able. This portrait mask tradition came to end in the early 1980s with the decline of Gbagba and while entertainment masks continue, they are no longer carved to represent specific individuals.

Portrait masks characteristically have an oval face with an elongated nose, a small, open mouth, and downcast slit eyes with projecting pieces that extend beyond the crest to suggest animal horns. Most also have scarification patterns at the temple and a high gloss patina. These stylistic attributes are actually a visual vocabulary that suggests what it means to be a good, honorable, respected, and beautiful person in Baule society. The half-slit eyes and high forehead suggest modesty and wisdom respectively. The nasolabial fold is depicted as a line between the sides of the nose to the outsides of the mouth and the beard-like projecting triangular patterns that extends from the bottom of the ears to the chin, suggest age. The triangular brass additions heighten the lustrous patina when danced in the sunlight, a suggestion of health.

An Ideal

The hairstyles of portrait-masks are known to be quite realistic but other features, like the six projecting tubular pieces at the crown, are abstract. This is not a realistic representation of the woman in the photograph, rather, it suggests an idealized inner state of beauty and morality associated with Moya Yanso.

Notice that Moya Yanso’s portrait mask is in the hands of her stepson in the photograph. Masking is the prerogative of men. While women attend masquerades as audience members and can perform with masked dancers, they do not wear or own masks themselves. The performers and makers of masks as well as those who commission them are always men.

From West Africa to the Midwest

Owie Kimou, Portrait Mask (Mblo) of Moya Yanso, Baule peoples (Côte d’Ivoire), early 20th century C.E., wood, brass, pigment, 36.2 cm high (private collection)

It is interesting to note the way in which African objects gather value in the West. This mask was acquired from the family of Moya Yanso in 1997 by a collector in Brussels, then sold to a French collector, and finally sold through the Sotheby’s auction house in 1999 for 197,000 US dollars to a collector in Minneapolis. The mask has also been exhibited at the Yale University Art Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum for African Art in New York. It is featured on the front cover of Baule: African Art, Western Eyes (1997) by Susan Vogel, who has written extensively on Baule art and first conducted fieldwork in Kami village in the 1960s.

For many collectors in the West, it is the formal properties of the mask that are alluring. Like the avant-garde artists in the early 20th century who were looking for new stylistic avenues to represent the modern condition, collectors today value the abstract qualities of Baule art. Vogel aptly notes that “Baule believers first encounter the object’s indwelling spiritual powers, or the metaphysical ideas it evokes, while the connoisseur begins with the visible forms, colors, textures—the artist’s material creation.” [2] Among the Baule up to the 1970s, this mask would remain hidden unless performed with musicians and dancers. To separate this mask from its masquerade is to give it new life as an aesthetic object.