Inspired by a spider’s web

Among the Asante (or Ashanti) people of Ghana, West Africa, a popular legend relates how two young men—Ota Karaban and his friend Kwaku Ameyaw—learned the art of weaving by observing a spider weaving its web. One night, the two went out into the forest to check their traps, and they were amazed by a beautiful spider’s web whose many unique designs sparkled in the moonlight. The spider, named Ananse, offered to show the men how to weave such designs in exchange for a few favors. After completing the favors and learning how to weave the designs with a single thread, the men returned home to Bonwire, and their discovery was soon reported to Asantehene Osei Tutu, first ruler of the Asante kingdom. The asantehene adopted their creation, named kente, as a royal cloth reserved for special occasions, and Bonwire became the leading kente weaving center for the asantehene and his court.

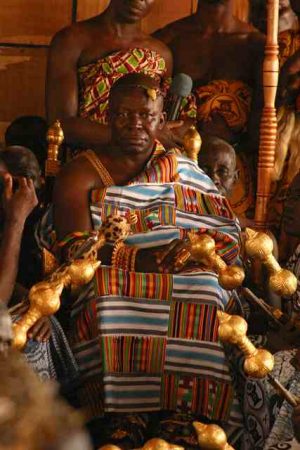

Asantehene Osei Tutu II wearing kente cloth, 2005 (photo: Retlaw Snellac, CC BY 2.0)

A royal cloth

Originally, the use of kente was reserved for Asante royalty and limited to special social and sacred functions. Even as production has increased and kente has become more accessible to those outside the royal court, it continues to be associated with wealth, high social status, and cultural sophistication. Kente is also found in Asante shrines to the deities, or abosom, as a mark of their spiritual power.

Historians maintain that kente cloth grew out of various weaving traditions that existed in West Africa prior to the formation of the Asante Kingdom. These techniques were appropriated through vast trade networks, as were materials such as French and Italian silk, which became increasingly desired in the 18th century and were combined with cotton and wool to make kente.

Kente cloth is also worn by the Ewe people, who were under the rule of the Asante kingdom in the late 18th century. It is believed that the Ewe, who had a previous tradition of horizontal loom weaving, adopted the style of kente cloth production from the Asante—with some important differences. Since the Ewe were not centralized, kente was not limited to use by royalty, though the cloth was still associated with prestige and special occasions. A greater variety in the patterns and functions exist in Ewe kente, and the symbolism of the patterns often has more to do with daily life than with social standing or wealth.

Weaving kente

Kente is woven on a horizontal strip loom, which produces a narrow band of cloth about four inches wide. Several of these strips are carefully arranged and hand-sewn together to create a cloth of the desired size. Most kente weavers are men.

Weaving involves the crossing of a row of parallel threads called the warp (threads running vertically) with another row called the weft (threads running horizontally). A horizontal loom, constructed with wood, consists of a set of two, four or six heddles (loops for holding thread), which are used for separating and guiding the warp threads. These are attached to treadles (foot pedals) with pulleys that have spools of thread inserted in them. The pulleys can be used to move the warp threads apart. As the weaver divides the warp threads, he uses a shuttle (a small wooden device carrying a bobbin, or small spool of thread) to insert the weft threads between them. These various parts of the loom, like the motifs in the cloth, all have symbolic significance and are accorded a great deal of respect.

Kente weaver in Adanwomase village, Ashanti Region, Ghana (photo: Shawn Zamechek, CC BY 2.0)

By alternating colors in the warp and weft, a weaver can create complex patterns, which in kente cloth are valued for both their visual effect and their symbolism. Patterns can exist vertically (in the warp), or horizontally (in the weft), or both.

A cloth with a name

Patterns each have a name, as does each cloth in its entirety. Names are sometimes given by weavers who obtain them through dreams or during contemplative moments when they are said to be in communion with the spiritual world. Alternatively, chiefs and elders may ascribe names to cloths that they specially commission. Names can be inspired by historical events, proverbs, philosophical concepts, oral literature, moral values, human and animal behavior, individual achievements, or even individuals in pop culture. In the past, when purchasing a cloth, the aesthetic and social appeal of the cloth’s was as important as—or sometimes even more important than—its visual pattern or color.

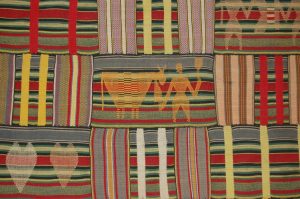

The King has Boarded the Ship (Asante kente cloth), c. 1985, rayon (collection of Dr. Courtnay Micots)

This cloth is named The King Has Boarded the Ship, and it includes both warp and weft patterns. The warp pattern, consisting of two multicolor stripes on blue, relates to the proverb “Fie buo yE buna,” meaning the head of the family has a difficult task. The weft patterns vary throughout the cloth; these examples are “NkyEmfrE,” a broken pot, and “Kwadum Asa,” an empty gunpowder keg.

The King has Boarded the Ship (details), left: “Broken Pot” pattern; right: “Empty Powder Keg” pattern, c. 1985, rayon (collection of Dr. Courtnay Micots)

Wearing kente

There are differences in how the cloth is worn by men and women. On average, a men’s size cloth measures 24 strips wide, making it about 8 feet wide and 12 feet long. Men usually wear one piece wrapped around the body, leaving the right shoulder and hand uncovered, in a toga-like style. Women may wear either one large piece or a combination of two or three pieces of varying sizes ranging from 5-12 strips, averaging of 6 feet long. Age, marital status, and social standing may determine the size and design of the cloth an individual would wear.

Men (left) and women (right) wearing kente at the Kente Cloth Festival in Kpetoe, September 2005 (photos: John Nash, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Social changes and modern living have brought about significant changes in how kente is used. It is no longer only the privilege of royalty; anyone who can afford it can buy kente. The old tradition of not cutting the cloth has also long been set aside, and it may be sewn into other forms such as dresses, shirts, or shoes. Printed versions of kente are mass produced and marketed, and both woven and printed versions are used by fashion designers in Ghana and abroad.

Kente print bag, 1990s (photo: Huzzah Vintage, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Kente is more than just a cloth. It is an iconic visual representation of the history, philosophy, ethics, oral literature, religious belief, social values, and political thought of West Africa. Kente is exported as one of the key symbols of African heritage and pride in African ancestry throughout the diaspora. In spite of the proliferation of both the hand-woven and machine-printed kente, the design is still regarded as a symbol of social prestige, nobility, and cultural sophistication.