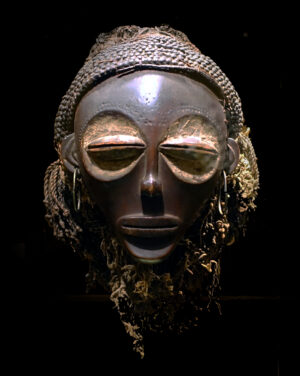

Female (pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of Congo, early 20th century, wood, plant fiber, pigment, copper alloy, 39.1 cm high (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington D.C.); Speakers: Dr. Peri Klemm and Dr. Beth Harris

Essay by Dr. Kristen Laciste

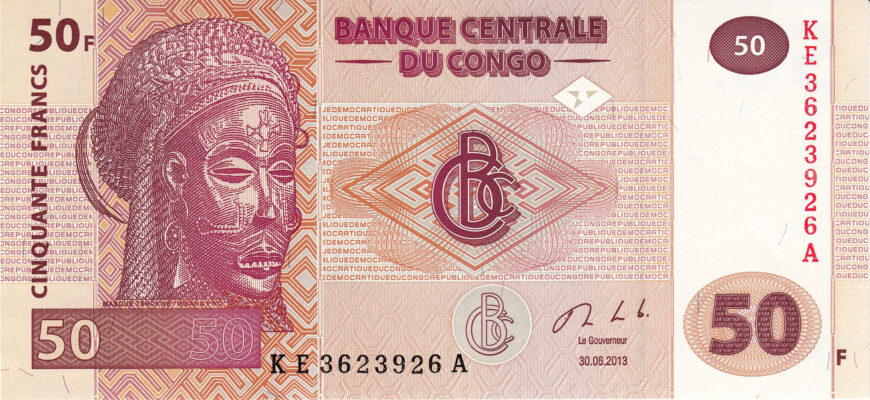

In Democratic Republic of the Congo, the currency that people generally use today is Congolese francs. The banknotes vary in color and range in denominations from 50 to 20,000 francs. They feature native flora and fauna, the Congo River, and works of art made by different linguistic and cultural groups. On one side of the 50 francs banknote is a three-quarter profile image of a Mwana Pwo mask, made by the Chokwe people.

The image on the Congolese 50 franc bill is characteristic of Mwana Pwo masks: sunken, concave eye sockets; large coffee-bean or almond shaped eyes that are partially closed; elongated, slender noses; curved ears; flattened, protruding lips; and carved facial patterns indicative of scarification marks or tattoos. Furthermore, this Mwana Pwo mask has an elaborate, braided coiffure, dangling earrings, and pointy lower teeth. Among the Chokwe and related peoples, the mask’s appearance and its performance convey ideals regarding feminine beauty and behavior.

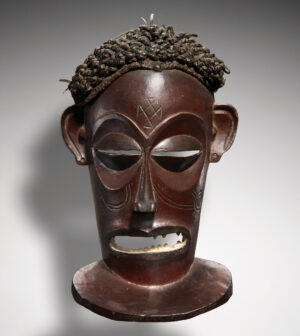

Mask, 1920–30, Chokwe, wood, vegetable fiber, glass beads, metal, 10 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (26.67 x 26.67 cm) (headdress), Angola or Democratic Republic of Congo (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Mwana Pwo in Men’s Initiations

Another female (pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of Congo, early 20th century, wood, plant fiber, pigment, copper alloy, 39.1 cm high (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington D.C.)

To become recognized as men in their communities, pre-adolescent boys undergo rites of passage during their initiations into manhood. Generally, men’s initiations among the Chokwe and related peoples include the separation of boys from their mothers, circumcision and healing from the procedure, instruction from men, and reincorporation into the larger community through coming-out ceremonies. Men’s initiations serve to move boys from the sphere of women and children to the sphere of men. While men’s initiations highlight gender-based divisions in the community, they rely on the participation of both men and women—especially the mothers of the boys.

In men’s initiations, masquerade characters appear in the community to educate, entertain, and keep women away from places where men’s initiations occur. Among the Chokwe and related peoples, masquerade characters are usually perceived as spirits of the deceased that take physical form through masked and costumed performers. Only men are allowed to perform as masquerade characters. One of these masquerade characters is Mwana Pwo (young woman), who portrays a young, fertile woman who has undergone women’s initiation ceremonies and is ready to marry and bear children. [1] While Mwana Pwo is sometimes abbreviated simply to Pwo (woman) and used interchangeably, some scholars interpret Pwo as a female ancestor or as a young woman who has already given birth to children. Despite these different interpretations, Mwana Pwo and Pwo present ideal womanhood among the Chokwe and related peoples. Similarly, groups in other parts of Africa, such as the Baga in Guinea, historically taught young men and women about ideal womanhood with the D’mba headdress.

Mask, 1920–30, Chokwe, wood, vegetable fiber, glass beads, metal, 10 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (26.67 x 26.67 cm) (headdress), Angola or Democratic Republic of Congo (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Mwana Pwo masks are carved from wood (or sometimes made with resin) by men. A songi (professional sculptor) who is commissioned to create a Mwana Pwo mask might model it on a particular woman in the community whose beauty he admires. Since he references a specific individual, there might be variations in the mask’s scarification patterns or tattoos, hairstyle, jewelry, and mouth. In the example at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Mwana Pwo mask has an oval-shaped face and symmetrical facial scarification marks (tattoos) on the middle of her forehead, underneath her eyes, and on her cheeks. Her eyebrows join together and form her slender nose bridge and nose. On the top of her forehead, she wears a braided headband or crown with beads made from plant fibers (likely raffia palm), and has intricately braided hair. Her mouth is partially open, revealing pointy, filed teeth (considered to be a marker of feminine beauty).

It is important to note that as displayed in the museum, the mask provides a limited glimpse of how Mwana Pwo appears to the community. In the museum space, the mask is a static work of art that is decontextualized. When performed during men’s initiations, Mwana Pwo is dynamic and engages with women in the community.

Female (pwo) mask, Chokwe peoples, Democratic Republic of Congo, early 20th century, wood, plant fiber, pigment, copper alloy, 39.1 cm high (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington D.C.)

Performing Mwana Pwo

As the atmosphere in the community can be tense during men’s initiations, masquerade characters like Mwana Pwo serve to “play with” and entertain the women and honor the mothers of the boys undergoing initiation. In addition to being made by a man, Mwana Pwo is danced by a man in front of an audience of women. The dancer outfits himself with the mask, as well as a tight-fitting crocheted costume, wooden breasts, skirts tied around the hips, and scarves. As part of the performance, the dancer might also carry objects such as a whistle or a flywhisk. Since the dancer is covered nearly or completely from head-to-toe, the dancers’ identity is concealed from the audience (though, women often know who is dancing).

Mwana Pwo engages the audience with hand gestures, dances, and songs. Through graceful and elegant speech and movements, Mwana Pwo models ideal feminine beauty and behavior. However, if women do not feel that a dancer performs well, they might chase away that dancer. Despite their interactions with the audience, Mwana Pwo and other masquerade characters are considered dangerous. If a masquerade character touches a person, it is believed that the individual will become sick, infertile, or suffer from other misfortunes.

Mask Representing a Male Ancestor (Chihongo), late 19th–early 20th century, wood, fiber, rattan, and metal. 10 13/16 × 6 11/16 × 3 9/16 in. (27.5 × 17 × 9 cm) (Yale University Art Gallery)

Complementing Mwana Pwo

The male counterpart of Mwana Pwo is the masquerade character, Cihongo. [3] Like Mwana Pwo, Cihongo is performed by a man during men’s initiations. Also like Mwana Pwo, there are different interpretations for Cihongo: the spirit of wealth, a royal character, or a chief. Cihongo is danced solely by the chief, his son, or his nephew.

Representing wealth, strength, and power, Cihongo is complementary to Mwana Pwo, who models ideal characteristics for women. Although they are complements, there is little documentation that Cihongo and Mwana Pwo perform alongside each other during men’s initiations. As with other characteristics of men’s initiations, this emphasizes the divisions between men and women in the community.

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to Dr. Elisabeth Cameron for additional insights and clarifications. Thank you also to Kadhitoza for pointing out that the image of the Mwana Pwo mask appears on Congolese francs.

Notes:

[1] Mwana Pwo is also referred to as Mwana wa Pwo in Luvale and Muana wa Mubanda in Lunda.

[2] Pwo is also referred to as Pwevo in western Zambia.

[3] Cihongo is also spelled as Chihongo.

Additional resources

“Masquerade”, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

Marie Louise Bastin, “Arts of the Angolan Peoples. I: Chokwe/L’Art d’un Peuple d’Angola. I: Chokwe,” African Arts, vol. 2, no. 1 (1968): 40-64.

Marie Louise Bastin, “Ritual masks of the Chokwe,” African Arts, vol. 17, no. 4 (1984): 40-44, 92-96.

Elisabeth L. Cameron, “Men portraying women: Representations in African masks,” African Arts, vol. 31, no. 2 (1998): pp. 72-94.

Elisabeth L. Cameron, “Potential and Fulfilled Woman: Initiations, Sculpture, and Masquerades in Kabompo District, Zambia,” in Chokwe!: Art and Initiation Among Chokwe and Related Peoples (1999), pp. 77-83.

Elisabeth L. Cameron, “Women= Masks: Initiation Arts in North-Western Province, Zambia,” African Arts, vol. 31, no. 2 (1998): 50-61, 93.

Manuel Jordán, “Engaging the Ancestors: Makishi Masquerades and the Transmission of Knowledge Among Chokwe and Related Peoples,” in Chokwe!: Art and Initiation Among Chokwe and Related Peoples (1999), pp. 67-76.

Manuel Jordán, “Revisiting Pwo,” African Arts, vol. 33, no. 4 (2000): 16-25, 92-93.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”pwo,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Peri Klemm: [0:09] We’re at the National Museum for African Art, and we’re looking at a mask made by the Chokwe people in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:16] This mask would have been danced by a male dancer, even though we’re looking at a mask that represents an ideal woman.

Dr. Klemm: [0:26] A masker who’s a man. And the carver, who’s a man, would have made this to honor women, particularly women who were young and fertile and had successfully given birth.

Dr. Harris: [0:36] There was an honor in Chokwe society given to those women, and this is also a culture that is matrilineal; that is, the family line is passed down through the mother.

Dr. Klemm: [0:45] One of the reasons to dance this mask was not only to honor women who were at this stage in life, but also to recognize the founding female ancestor of the Chokwe lineage.

Dr. Harris: [0:51] It’s made of a wood that’s very thin and difficult to carve. We see fiber and this elaborate hairstyle. We have to imagine the rest of the costume that would have been here when the mask was danced.

Dr. Klemm: [1:09] This would have been a tight-fitted body stocking covered in raffia cloth. The dancer’s groin area would be covered in a loincloth, and he’d be wearing wooden breasts.

Dr. Harris: [1:21] We’re using the word dance, but from the descriptions, the dancer walked in a very graceful and stately way.

Dr. Klemm: [1:34] Chokwe women actually do dance like that. That’s very graceful and fluid and slow and respectful. When we say he’s wearing a woman’s face and he’s wearing women’s breasts, he’s not impersonating a woman. He’s really meant to honor women who have courageously gone through childbirth and retain this inner wisdom and beauty so beautifully articulated in the facial features.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] We see that sense of calm in the face.

Dr. Klemm: [1:56] The fact that her eyes are closed, her mouth is closed, suggest a turning inward. She’s not talking. She doesn’t need to talk at this point in life. She deserves respect, and she doesn’t have to open her eyes wide. She’s already knowing.

[2:05] The mask itself is a deep dark red, which was probably created through a mixture of red earth and oil, but there’s white kaolin or white powder around her eyes. This whiteness is connected to the spiritual realm.

[2:20] In fact, her eyes are the most important part of the face. They’re abstractly big, and it draws attention to the fact that she has the spiritual ability almost of second sight, that her power comes from being able to give birth.

Dr. Harris: [2:34] The face is very symmetrical. The chin comes to a narrower point. The broadest part of the face is by the eyes and the ears, this wide forehead that is accentuated by the hairstyle.

Dr. Klemm: [2:53] We have these constant circles that are bisected by the lines of the mouth or the eyes. Then we also have the circle of the earring in the ear. This mask was obviously really loved. In fact, we can see a repair on one side of the face so that they could continue to use it.

[3:06] We also have pounded dots around the eyes, which further emphasizes their cylindrical nature, but also suggests women’s tattoo patterns. Women wore a whole host of different tattoo designs that had special references and special meaning.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] The Chokwe people were little known until the earlier part of the 20th century, by Europeans.

Dr. Klemm: [3:28] Europeans, and particularly Portuguese, didn’t begin trading with the Chokwe until the early 1900s. They weren’t documented and such in the way that other groups were. However, the Chokwe had been part of a larger kingdom from which they broke away.

[3:42] They had had trading relations with many groups throughout Africa. They certainly didn’t exist in isolation.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] There are about a million today in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dr. Klemm: [4:04] As this mask shows us the ideal woman, ideal virtues, her hairstyle would’ve been fashionable at the time. They could really see themselves in the mask when it was being performed for them.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] This is an ideal of womanhood in so many ways.

[0:00] [music]